Reproductive Behavior of the Swimming Crab <I>Arenaeus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Classification of Living and Fossil Genera of Decapod Crustaceans

RAFFLES BULLETIN OF ZOOLOGY 2009 Supplement No. 21: 1–109 Date of Publication: 15 Sep.2009 © National University of Singapore A CLASSIFICATION OF LIVING AND FOSSIL GENERA OF DECAPOD CRUSTACEANS Sammy De Grave1, N. Dean Pentcheff 2, Shane T. Ahyong3, Tin-Yam Chan4, Keith A. Crandall5, Peter C. Dworschak6, Darryl L. Felder7, Rodney M. Feldmann8, Charles H. J. M. Fransen9, Laura Y. D. Goulding1, Rafael Lemaitre10, Martyn E. Y. Low11, Joel W. Martin2, Peter K. L. Ng11, Carrie E. Schweitzer12, S. H. Tan11, Dale Tshudy13, Regina Wetzer2 1Oxford University Museum of Natural History, Parks Road, Oxford, OX1 3PW, United Kingdom [email protected] [email protected] 2Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, 900 Exposition Blvd., Los Angeles, CA 90007 United States of America [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 3Marine Biodiversity and Biosecurity, NIWA, Private Bag 14901, Kilbirnie Wellington, New Zealand [email protected] 4Institute of Marine Biology, National Taiwan Ocean University, Keelung 20224, Taiwan, Republic of China [email protected] 5Department of Biology and Monte L. Bean Life Science Museum, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT 84602 United States of America [email protected] 6Dritte Zoologische Abteilung, Naturhistorisches Museum, Wien, Austria [email protected] 7Department of Biology, University of Louisiana, Lafayette, LA 70504 United States of America [email protected] 8Department of Geology, Kent State University, Kent, OH 44242 United States of America [email protected] 9Nationaal Natuurhistorisch Museum, P. O. Box 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands [email protected] 10Invertebrate Zoology, Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History, 10th and Constitution Avenue, Washington, DC 20560 United States of America [email protected] 11Department of Biological Sciences, National University of Singapore, Science Drive 4, Singapore 117543 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 12Department of Geology, Kent State University Stark Campus, 6000 Frank Ave. -

DISTRIBUTION PATTERNS of Arenaeus Cribrarius (LAMARCK, 1818) (CRUSTACEA, PORTUNIDAE) in FORTALEZA BA~ UBATUBA (SP), BRAZIL

DISTRIBUTION PATTERNS OF Arenaeus cribrarius (LAMARCK, 1818) (CRUSTACEA, PORTUNIDAE) IN FORTALEZA BA~ UBATUBA (SP), BRAZIL 2 MARCELO ANTONIO AMARO PINHEIRO1,3, ADILSON FRANSOZ0 ,3 2 and MARIA LUCIA NEGREIROS-FRANSOZ0 ,3 lDepartamento de Biologia Aplicada, Faculdade de Ciencias Agnirias e Veterimirias, UNESP, Campus de Iaboticabal - 14870-000 - Iaboticabal, SP, Brasil 2Departamento de Zoologia, Instituto de Biociencias, Cx. Postal 502, UNESP, Cam£us de Botucatu - 18618-000 - Botucatu, SP, Brasil Centro de Aqiiicultura da UNESP (CAUNESP), Nticleo de Estudos em Biologia, Ecologia e Cultivo de Crusmceos (NEBECC) (With 6 figures) ABSTRACT The abundance of the swimming crab A. cribrarius in Fortaleza Bay, Ubatuba (SP) was ana lysed in order to detect the influence of some environmental factors in its distribution. The collections were made by using two otter-trawls deployed from a shrimp-fishing vessel and occurred monthly during one year. The Fortaleza Bay was sampled in 7 radials of I Ian each. Each environmental factor (temperature, salinity and dissolved oxygen of the bottom water, depth, granulometric composition and organic matter of the sediment), sampled in the middle point of each transect, was correlated with the abundance of 5 groups (adult males, ovigerous females, non-ovigerous adult females, juveniles, and total number of specimens), by Pear son's linear and canonical correlation analyses. The total amount of specimens revealed a positive linear correlation with temperature and very fine sand fraction, and a negative linear correlation with organic material contents. Different association patterns appeared in relation to the abundance of the groups mentioned above, such as depth and granulometry. Ovigerous females were the only group which was associated with the whole set of granulometric frac tions of the sediment. -

Molecular Phylogeny of the Western Atlantic Species of the Genus Portunus (Crustacea, Brachyura, Portunidae)

Blackwell Publishing LtdOxford, UKZOJZoological Journal of the Linnean Society0024-4082The Lin- nean Society of London, 2007? 2007 1501 211220 Original Article PHYLOGENY OF PORTUNUS FROM ATLANTICF. L. MANTELATTO ET AL. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2007, 150, 211–220. With 3 figures Molecular phylogeny of the western Atlantic species of the genus Portunus (Crustacea, Brachyura, Portunidae) FERNANDO L. MANTELATTO1*, RAFAEL ROBLES2 and DARRYL L. FELDER2 1Laboratory of Bioecology and Crustacean Systematics, Department of Biology, FFCLRP, University of São Paulo (USP), Ave. Bandeirantes, 3900, CEP 14040-901, Ribeirão Preto, SP (Brazil) 2Department of Biology, Laboratory for Crustacean Research, University of Louisiana at Lafayette, Lafayette, LA 70504-2451, USA Received March 2004; accepted for publication November 2006 The genus Portunus encompasses a comparatively large number of species distributed worldwide in temperate to tropical waters. Although much has been reported about the biology of selected species, taxonomic identification of several species is problematic on the basis of strictly adult morphology. Relationships among species of the genus are also poorly understood, and systematic review of the group is long overdue. Prior to the present study, there had been no comprehensive attempt to resolve taxonomic questions or determine evolutionary relationships within this genus on the basis of molecular genetics. Phylogenetic relationships among 14 putative species of Portunus from the Gulf of Mexico and other waters of the western Atlantic were examined using 16S sequences of the rRNA gene. The result- ant molecularly based phylogeny disagrees in several respects with current morphologically based classification of Portunus from this geographical region. Of the 14 species generally recognized, only 12 appear to be valid. -

Invertebrate ID Guide

11/13/13 1 This book is a compilation of identification resources for invertebrates found in stomach samples. By no means is it a complete list of all possible prey types. It is simply what has been found in past ChesMMAP and NEAMAP diet studies. A copy of this document is stored in both the ChesMMAP and NEAMAP lab network drives in a folder called ID Guides, along with other useful identification keys, articles, documents, and photos. If you want to see a larger version of any of the images in this document you can simply open the file and zoom in on the picture, or you can open the original file for the photo by navigating to the appropriate subfolder within the Fisheries Gut Lab folder. Other useful links for identification: Isopods http://www.19thcenturyscience.org/HMSC/HMSC-Reports/Zool-33/htm/doc.html http://www.19thcenturyscience.org/HMSC/HMSC-Reports/Zool-48/htm/doc.html Polychaetes http://web.vims.edu/bio/benthic/polychaete.html http://www.19thcenturyscience.org/HMSC/HMSC-Reports/Zool-34/htm/doc.html Cephalopods http://www.19thcenturyscience.org/HMSC/HMSC-Reports/Zool-44/htm/doc.html Amphipods http://www.19thcenturyscience.org/HMSC/HMSC-Reports/Zool-67/htm/doc.html Molluscs http://www.oceanica.cofc.edu/shellguide/ http://www.jaxshells.org/slife4.htm Bivalves http://www.jaxshells.org/atlanticb.htm Gastropods http://www.jaxshells.org/atlantic.htm Crustaceans http://www.jaxshells.org/slifex26.htm Echinoderms http://www.jaxshells.org/eich26.htm 2 PROTOZOA (FORAMINIFERA) ................................................................................................................................ 4 PORIFERA (SPONGES) ............................................................................................................................................... 4 CNIDARIA (JELLYFISHES, HYDROIDS, SEA ANEMONES) ............................................................................... 4 CTENOPHORA (COMB JELLIES)............................................................................................................................ -

Larval Development of the Speckled Swimming Crab, <I>Arenaeus Cribrarius</I> (Decapoda: Brachyura: Portunidae) Reare

BULLETIN OF MARINE SCIENCE, 42(1): 101-132, 1988 LARVAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE SPECKLED SWIMMING CRAB, ARENAEUS CRIBRARIUS (DECAPODA: BRACHYURA: PORTUNIDAE) REARED IN THE LABORATORY Kenneth C. Stuck and Frank M. Truesdale ABSTRACT Eight zoeal stages and a megalopa of the speckled swimming crab, Arenaeus cribrarius, are described and figured from larvae of an ovigerous specimen collected at Hom Island, Mis- sissippi (Gulf of Mexico). Crab stages 1-3 are also briefly described. Larvae were reared at 25°C and 300/00salinity; some individuals completed zoeal development in 30 days,and reached crab I, 13 days later. Zoea I characters of A. cribrarius are compared with those of seven other species of shallow water Gulf Portuninae, from larvae reared by the authors, and from the literature. Antennal and telson features are important in distinguishing among zoeae I ofGulfPortuninae. Characters ofzoeae II-VIII and the megalopa of A. cribrarius and those of corresponding stages of Callinecles sapidus, C. similis. and PorlUnus spinicarpus from the literature are compared. In zoeae III and VI, setation of maxillar basal and coxal endites is a distinguishing feature among A. cribrarius, C. sapidus, C. similis, and P. spinicarpus, and in zoea V, maxillular basal and coxal endite setation distinguish each. Antennular aesthetasc formula distinguishes each species having a zoea VIII, and in all zoeal stages this feature distinguishes A. cribrarius from the others. Zoeae IV and VII of C. sapidus, C. similis and P. spinicarpus can be separated by setation of maxillular basal and coxal endites, and in zoea II this same feature distinguishes P. spinicarpus from C. -

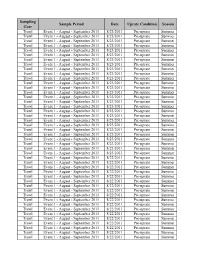

St. Lucie, Units 1 and 2

Sampling Sample Period Date Uprate Condition Season Gear Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event 1 - August - September 2011 8/23/2011 Pre-uprate Summer Trawl Event -

Population Biology and Distribution of the Portunid Crab Callinectes Ornatus (Decapoda: Brachyura) in an Estuary-Bay Complex of Southern Brazil

ZOOLOGIA 31 (4): 329–336, August, 2014 http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-46702014000400004 Population biology and distribution of the portunid crab Callinectes ornatus (Decapoda: Brachyura) in an estuary-bay complex of southern Brazil Timoteo T. Watanabe1,3, Bruno S. Sant’Anna1, Gustavo Y. Hattori1 & Fernando J. Zara2 1 Programa de Pós-graduação em Ciência e Tecnologia para Recursos Amazônicos, Instituto de Ciências Exatas e Tecnologia, Universidade Federal do Amazonas. 69103-128 Itacoatiara, AM, Brazil. 2 Invertebrate Morphology Laboratory, Universidade Estadual Paulista, CAUNESP and IEAMar, Departamento de Biologia Aplicada, Campus de Jaboticabal, 14884-900 Jaboticabal, SP, Brazil. 3 Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT. Trawl fisheries are associated with catches of swimming crabs, which are an important economic resource for commercial as well for small-scale fisheries. This study evaluated the population biology and distribution of the swimming crab Callinectes ornatus (Ordway, 1863) in the Estuary-Bay of São Vicente, state of São Paulo, Brazil. Crabs were collected from a shrimp fishing boat equipped with a semi-balloon otter-trawl net, on eight transects (four in the estuary and four in the bay) from March 2007 through February 2008. Specimens caught were identified, sexed and measured. Samples of bottom water were collected and the temperature and salinity measured. A total of 618 crabs were captured (332 males, 267 females and 19 ovigerous females), with a sex ratio close to 1:1. A large number of juveniles were captured (77.67%). Crab spatial distributions were positively correlated with salinity (Rs = 0.73, p = 0.0395) and temperature (Rs = 0.71, p = 0.0092). -

Chromatic Alteration in Arenaeus Cribrarius (Lamarck) (Crustacea, Portunidae): an Indicator of Sexual Maturity

Chromatic alteration in Arenaeus cribrarius (Lamarck) (Crustacea, Portunidae): an indicator of sexual maturity Marcelo Antonio Amaro Pinheiro 1 Fabiano Gazzi Taddei 1,2 ABSTRACT. Some individuals of the species Arenaeus cribrarills (Lamarck, 1818) bear a characteristic pink abdomen, which is notably different Ii-OIn the usual white coloration. The incidence of this chromatic alteration was determined for a single population and its relation with other individual variables were examined. The individuals were monthly collected from May, 1991 to April, 1993, in Ubatuba, Sao Paulo, with the aid of a shrimp fi shelY boat provided with double-rig trawling nets. All specimens were sexed, measured (CW = carapace width), di stributed in 10-mm size classes and classified according to growth phase (juvenile and adult), molting condition and development stage of gonads. The occurrence of pink-colored morphs was also recorded. From a total of2,096 collected individuals, only 60 females (nine of those ovigerous) presented a pink-colored abdomen, which represents 2.9% of the whol e sample and 5.2% of the females. Almost all of them were inte1l110it individuals (96.6%) and 63.3% showed mature gonads. According to published data, size at the onset offunctional maturity in A. cribrarills females is around 60 mm CW, ti'om which the incidence of pink morphs and ovigerous crabs were recorded. The obtained results suggest that such a chromatic alteration is associated to sexual maturity in these females. This characteristi c may enhance the attraction potential for mating, shonly after the puberty molt. KEY WORDS . Brachyura , Portunidae, re pro ~ ucti o l1 , coloration During the past few years, changes in the coloration patterns related to the breeding period of several animal species, and mainly its role in attraction for mating, have received the attention of many researchers. -

Decapod Crustacean Chelipeds: an Overview

Journal of Biophysical Chemistry, 2009, 1, 1-13 Decapod crustacean chelipeds: an overview PITCHAIMUTHU MARIAPPAN, CHELLAM BALASUNDARAM and BARBARA SCHMITZ The structure, growth, differentiation and function of crustacean chelipeds are reviewed. In many decapod crusta- ceans growth of chelae is isometric with allometry level reaching unity till the puberty moult. Afterwards the same trend continues in females, while in males there is a marked spurt in the level of allometry accompanied by a sud- den increase in the relative size of chelae. Subsequently they are differentiated morphologically into crusher and cutter making them heterochelous and sexually dimorphic. Of the two, the major chela is used during agonistic encounters while the minor is used for prey capture and grooming. Various biotic and abiotic factors exert a negative effect on cheliped growth. The dimorphic growth pattern of chelae can be adversely affected by factors such as parasitic infection and substrate conditions. Display patterns of chelipeds have an important role in agonistic and aggressive interactions. Of the five pairs of pereiopods, the chelae are versatile organs of offence and defence which also make them the most vulnerable for autotomy. Regeneration of the autotomized chelipeds imposes an additional energy demand called “regeneration load” on the incumbent, altering energy allocation for somatic and/or reproductive processes. Partial withdrawal of chelae leading to incomplete exuvia- tion is reported for the first time in the laboratory and field in Macrobrachium species. 1. General morphology (exites) or medial (endites) protrusions (Manton 1977; McLaughlin 1982). From the protopod arise the exopod Chelipeds of decapod crustaceans have attracted human and endopod. -

Decapoda (Crustacea) of the Gulf of Mexico, with Comments on the Amphionidacea

•59 Decapoda (Crustacea) of the Gulf of Mexico, with Comments on the Amphionidacea Darryl L. Felder, Fernando Álvarez, Joseph W. Goy, and Rafael Lemaitre The decapod crustaceans are primarily marine in terms of abundance and diversity, although they include a variety of well- known freshwater and even some semiterrestrial forms. Some species move between marine and freshwater environments, and large populations thrive in oligohaline estuaries of the Gulf of Mexico (GMx). Yet the group also ranges in abundance onto continental shelves, slopes, and even the deepest basin floors in this and other ocean envi- ronments. Especially diverse are the decapod crustacean assemblages of tropical shallow waters, including those of seagrass beds, shell or rubble substrates, and hard sub- strates such as coral reefs. They may live burrowed within varied substrates, wander over the surfaces, or live in some Decapoda. After Faxon 1895. special association with diverse bottom features and host biota. Yet others specialize in exploiting the water column ment in the closely related order Euphausiacea, treated in a itself. Commonly known as the shrimps, hermit crabs, separate chapter of this volume, in which the overall body mole crabs, porcelain crabs, squat lobsters, mud shrimps, plan is otherwise also very shrimplike and all 8 pairs of lobsters, crayfish, and true crabs, this group encompasses thoracic legs are pretty much alike in general shape. It also a number of familiar large or commercially important differs from a peculiar arrangement in the monospecific species, though these are markedly outnumbered by small order Amphionidacea, in which an expanded, semimem- cryptic forms. branous carapace extends to totally enclose the compara- The name “deca- poda” (= 10 legs) originates from the tively small thoracic legs, but one of several features sepa- usually conspicuously differentiated posteriormost 5 pairs rating this group from decapods (Williamson 1973). -

ASPECTOS BIOECOLÓGICOS DE ARENAEUS CRIBRARJUS (LAMARCK) (DECAPODA, PORTUNIDAE) DA PRAIA DA BARRA DA LAGOA, Florianópolls, SANTA CATARINA, BRASIL

ASPECTOS BIOECOLÓGICOS DE ARENAEUS CRIBRARJUS (LAMARCK) (DECAPODA, PORTUNIDAE) DA PRAIA DA BARRA DA LAGOA, FLORIANÓPOLlS, SANTA CATARINA, BRASIL Marcelo Gentil Avila 1, 2 Joaquim Olinto Branco 1,3 ABSTRACT. BIOECOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF A RENA EUS CRIBRAR/US (LAMARCK) (DECAPO DA, PORTUN IDA E) FROM PRA IA DA BARRA DA LAGOA, FLORIANOPOI.IS, SANTA CATARINA, BRA SIL. The specimens of Arenaeus cribrarius (Lamarck, 1818) used in this study were collected in the locality ofBarra da Lagoa beach, Florianópolis, Santa Catarina, Brazil, in the period of April/1991 to March/ 1992. ln this area temperature and salinity values were observed. A total of 341 samples, that 184 were male and 157 were female were collectted. The maturacion sexual stadium were measured (cm) and weightied (g). Expression of relation among weight of body (wt) and width of carapace (wid) 3 2 was Wt=O,0567 Wid ,0494 on males and wt=O,074 Wid ,8795 0 11 females. The relatiol1 length (Lt) width (wid) ofcarapace was Lt=O,4322. wid on males and Lt=O,4578. wid on females. KEY WORDS. Portunidae, Arenaeus cribrarius, length, width, weigth Arenaeus cribrarius (Lamarck, 1818), conhecido popularmente como siri chita, ocorre no Oceano Atlântico de Vineyard Sound, Massachusets nos Estados Unidos, a La Paloma no Uruguai (JUANICÓ 1978; WILLIAMS 1984). No Brasi l, a espécie é citada nos trabalhos de levantamento faunístico d e: ABREU (1975); FAUSTO-FILHO (1979); SAMPAIO & FAUSTO-FILHO (1984); M ELO (1985); GOUVÊA (1986); MOREIRA et aI, (1988); BRANCO et ai. (1990) e L UNARDON-BRANCO (1993), Trabalhos abordando aspectos do ciclo de vida como o desenvolvimento larval: STUCK & TRUESDALE (1988); influência de parâmetros hidrológicos na distribuição: ANDERSON et ai. -

Exceptional Preservation of Mid-Cretaceous Marine Arthropods and the Evolution of Novel Forms Via Heterochrony J

SCIENCE ADVANCES | RESEARCH ARTICLE PALEONTOLOGY Copyright © 2019 The Authors, some rights reserved; Exceptional preservation of mid-Cretaceous exclusive licensee American Association marine arthropods and the evolution of novel forms for the Advancement of Science. No claim to via heterochrony original U.S. Government J. Luque1,2,3*, R. M. Feldmann4, O. Vernygora1, C. E. Schweitzer5, C. B. Cameron6, K. A. Kerr2,7, Works. Distributed 8 9 10 1 2 under a Creative F. J. Vega , A. Duque , M. Strange , A. R. Palmer , C. Jaramillo Commons Attribution NonCommercial License 4.0 (CC BY-NC). Evolutionary origins of novel forms are often obscure because early and transitional fossils tend to be rare, poorly preserved, or lack proper phylogenetic contexts. We describe a new, exceptionally preserved enigmatic crab from the mid-Cretaceous of Colombia and the United States, whose completeness illuminates the early disparity of the group and the origins of novel forms. Its large and unprotected compound eyes, small fusiform body, and leg-like mouthparts suggest larval trait retention into adulthood via heterochronic development (pedomorphosis), while its large oar-like legs represent the earliest known adaptations in crabs for active swimming. Our phylogenetic Downloaded from analyses, including representatives of all major lineages of fossil and extant crabs, challenge conventional views of their evolution by revealing multiple convergent losses of a typical “crab-like” body plan since the Early Cretaceous. These parallel morphological transformations