Fostering Resilience in Correctional Officers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[Af]: Devils Dye Pdf, Epub, Ebook](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7984/af-devils-dye-pdf-epub-ebook-197984.webp)

[Af]: Devils Dye Pdf, Epub, Ebook

BLACK [AF]: DEVILS DYE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Vita Ayala | 112 pages | 02 Feb 2021 | Epitaph | 9781628752427 | English | Los Angeles, United States Black [AF]: Devils Dye PDF Book Episode Night Argent. Episode Carley Coma Candiria. During our conversation, Stagg shares her motivation in photographing naked ladies, the diversity she strived for in this book, the artistry of her work, and the business side of working with these women. Karnal Confessions Kickstarter: kck. Anastasia Lin is an award-winning actress, former Miss World Canada and human rights activist, and has appeared in over 20 films and television productions. At the end of each interview, I close out with the same question that I give to them ahead of time to think about it. Here we show the last 14 days that actually had sales. During our conversation, we talked about how she used beauty pageants as her platform for activism, why she didn't quit after China start threatening her family, how being an actress helps with her activism, her dealings with the Chinese government, the making of the documentary, and her future plans. Follow Joe Corallo: Twitter: twitter. Indigo, together with former Detective Ellen Waters race to find the source of the substance poisoning their people, before it's too late! We sell sportscards,gaming cards,comic books,action figures,plush toys and various other hobby related items. Hayes and co-written and directed by Episode guest Brian Skiba. Issue ST Pre-publication image; subject to change. With Kanif The Jhatmaster on production for the entire album, their chemistry is unparalleled with a sound that takes a nod to old school trip hop. -

NEW RELEASE GUIDE September 3 September 10 ORDERS DUE JULY 30 ORDERS DUE AUGUST 6

ada–music.com @ada_music NEW RELEASE GUIDE September 3 September 10 ORDERS DUE JULY 30 ORDERS DUE AUGUST 6 2021 ISSUE 19 September 3 ORDERS DUE JULY 30 SENJUTSU LIMITED EDITION SUPER DELUXE BOX SET Release Date: September 3, 2021 INCLUDES n Standard 2CD Digipak with 28-page booklet n Blu-Ray Digipak • “The Writing On The Wall” • Making Of “The Writing On The Wall” • Special Notes from Bruce Dickinson • 20-page booklet n 3 Illustrated Art Cards n 3D Senjutsu Eddie Lenticular n Origami Sheet with accompanying instructions to produce an Origami version of Eddie’s Helmet, all presented in an artworked envelope n Movie-style Poster of “The Writing On The Wall” n All housed in Custom Box made of durable board coated with a gloss lamination TRACKLIST CD 1 1. Senjutsu (8:20) 2. Stratego (4:59) 3. The Writing On The Wall (6:23) 4. Lost In A Lost World (9:31) 5. Days Of Future Past (4:03) 6. The Time Machine (7:09) CD 2 7. Darkest Hour (7:20) 8. Death of The Celts (10:20) 9. The Parchment (12:39) 10. Hell On Earth (11:19) BLU-RAY • “The Writing On The Wall” Video • “The Writing On The Wall” The Making Of • Special notes from Bruce Dickinson LIMITED EDITION SUPER DELUXE BOX SET List Price: $125.98 | Release Date: 9/3/21 | Discount: 3% Discount (through 9/3/21) Packaging: Super Deluxe Box | UPC: 4050538698114 Returnable: YES | Box Lot: TBD | Units Per Set: TBD | File Under: Rock SENJUTSU Release Date: September 3, 2021 H IRON MAIDEN Take Inspiration From The East For Their 17th Studio Album, SENJUTSU H Brand new double album shows band maintain -

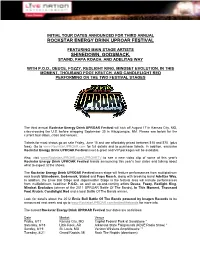

Release 6 11 12 UPROAR Dates FINAL 6.11.2012 8AM ET

INITIAL TOUR DATES ANNOUNCED FOR THIRD ANNUAL ROCKSTAR ENERGY DRINK UPROAR FESTIVAL FEATURING MAIN STAGE ARTISTS SHINEDOWN, GODSMACK, STAIND, PAPA ROACH, AND ADELITAS WAY WITH P.O.D., DEUCE, FOZZY, REDLIGHT KING, MINDSET EVOLUTION, IN THIS MOMENT, THOUSAND FOOT KRUTCH, AND CANDLELIGHT RED PERFORMING ON THE TWO FESTIVAL STAGES The third annual Rockstar Energy Drink UPROAR Festival will kick off August 17 in Kansas City, MO, criss-crossing the U.S. before wrapping September 30 in Albuquerque, NM. Please see below for the current tour dates, cities and venues. Tickets for most shows go on sale Friday, June 15 and are affordably priced between $15 and $75 (plus fees). Go to www.RockstarUPROAR.com for full details and to purchase tickets. In addition, exclusive Rockstar Energy Drink UPROAR Festival meet & greet and VIP packages will be available. Also, visit www.RockstarUPROAR.com/UPROARTV to see a new video clip of some of this year’s Rockstar Energy Drink UPROAR Festival bands announcing this year’s tour dates and talking about what to expect at the shows. The Rockstar Energy Drink UPROAR Festival main stage will feature performances from multiplatinum rock bands Shinedown , Godsmack , Staind and Papa Roach , along with breaking band Adelitas Way . In addition, the Ernie Ball Stage and Jägermeister Stage in the festival area will include performances from multiplatinum headliner P.O.D. , as well as up-and-coming artists Deuce , Fozzy , Redlight King , Mindset Evolution (winner of the 2011 UPROAR Battle Of The Bands), In This Moment , Thousand Foot Krutch , Candlelight Red and a local Battle Of The Bands winner. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE October 14, 2014

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE October 14, 2014 SHAMAN'S HARVEST ANNOUNCES EXTENSIVE WINTER TOUR Band To Appear As Support For Fozzy Following Headline Run Beginning 11/10 Smokin' Hearts & Broken Guns Continues To Perform At Retail Following #5 Billboard "Heatseekers" Debut Fueled By Charting Active Rock Single "Dangerous" Video Can Be Viewed Here : http://youtu.be/V9c44jhm_II New York, NY --- Mascot Label Group recording artist Shaman's Harvest will begin a tour on November 11 that will hit dozens of markets across the U.S. Following headline appearances in CO, ID, WA, UT and NE, they'll meet up with Fozzy and Texas Hippie Coalition on November 20th in Flint, MI. That run will continue through mid-December. Over the past couple of months, Shaman's Harvest has been performing to standing room only crowds throughout their home turf in Midwestern markets, where their recent release SMOKIN' HEARTS & BROKEN GUNS is a best-seller are retail. As Shaman's Harvest heads out for this string of headline shows, front man Nathan Hunt offers, "We've been prepping for this tour to play for all the markets in the country that'll have us. I don't mean ironing out the kinks. I mean taking our Sunday best, wadding it up in a ball, throwin' it in the Mississippi for a good week, then puttin' that shit on just in time to take y'all to church. We're all gonna be speakin' in tongues when this is over." On the opportunity of then joining Fozzy and Texas Hippie Coalition, he shares, "We're stoked to be on a bill that has three very different styles of rock n' roll. -

U·Rvl-T University Microfilms International a Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, M148106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copysubmitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, ifunauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand cornerand continuingfrom leftto right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. These are also available as one exposure on a standard 35mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copyfor an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. U·rvl-T University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, M148106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 ---._-._---_.• ------------- Order Number 9018995 High tea at Halekulani: Feminist theory and American clubwomen Misangyi Watts, Margit, Ph.D. -

1 0 Million Scholarship Fund Settles Tuition Suit

. VOLUME 38 June 13, 2005 ISSUE Your source for campus news and infonnation 1154 See page 8 'Cinderella Man' packs a real punch THECURRENTONLINE.COM ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~.UNIV ERSITV OFMI SSOUR I -S~ LOUIS '" NY Yankees draft $1 0 million scholarship UMSL's star hitter fund settles tuition suit Josh Morgan led the BY MIKE SHERWIN a class action lawsuit against the UM 1993. System The Missouri Legislature amended Terms of the Editor-in-Cbie! team this Spring with Herman based his lawsuit on a the statute to allow for collection of settlement: Over 100,000 former students of the Missouri statute originally passed in tuition in 200 1. ,586 batting average UM system's four campuses could be 1872 that stated, "All youths, resident Former UM System President - $1 million to Roben Hem1an, eligible for a portion of a $10 million of the state of Missouri, over the age of Manuel Pachecho testified in Dec. the attorney who filed the suit scholarship fund, as part of a tentative sixteen years, shall be admitted to all 2001 that "educational fees" and BY .JAMES DAUGHERTY settlement announced May 18. the privileges and advantages of the "tuition" were not the same, and that a plus $17,000 for expenses Sports Editor A St Louis County Circuit Court various classes of the University of the total refund of in-state tuition to stu - $27,000 for the three students judge still must approve the agreement State of Missouri without payment of dents since 1993 could total as much as after an actuary finalizes details of how tuition ..." $450 million, named as plaintiffs in tl1e case ~J Junior outfielder and pitcher Josh the scholarship fund will be set up and In 1986, the UM system changed St. -

Rrie S 0 JECTOR December 2, 2002

OPEN EVERY DAY ?IL MIDNIGHT NEWS RECYCLE ENTERTAINMENT YOUR MOVIE DVDs Smoke Getting CDs, VHS & GAMES 700 BUY - SELL - TRADE - RENT clears on Headstoned at CHOOSE R RRC fire the Pyramid RECYCLE1/011,,JVC safety plan Cabaret, page 3 page 10 DVDs, VHS a GAMES DVDs IN THE VILLAGE 475-0077 rn, sictrader.ca IN THE VILLAGE 477-5566 movievillage.ca RED RIVER COLLEGE'S NEWSPAPER rriE ■ 0 JECTOR December 2, 2002 Canada's ambassador to Iran visits new campus By Natalie Pona ties allowed in Iran, and the The same UN report said ran is a country mis- country's government and Iranians are struggling to understood by the laws are based on the Islamic reform the country, working religion. against the interests of the Western world, says MacKinnon said most peo- powerful Islamic govern- Canada's ambassador to the ple in Iran want to develop ment. Middle Eastern republic. beyond the traditional laws MacKinnon said the people Philip MacKinnon spoke to imposed by the government, of Iran want free enterprise students at Red River the same laws that have led and human rights but not College's Princess Street cam- to human rights violations. the what they see are the pus on Nov. 12 about his "Eighty per cent of excesses of the Western experiences as an ambassador Iranians want to go this world. Iranians don't want to to the country sandwiched route," he said. "It's a com- be considered pro-American, between the volatile Iraq and plicated situation in Iran. a title MacKinnon said is in Pakistan, a country reputed Those who are in power feel opposition to the values of to harbour al Qaeda opera- `if we liberalize, we'll lose the people of Iran. -

Download Festival Tag Teams with Wwe Nxt This Summer

**NEWS** EMBARGOED UNTIL 10:00AM GMT WEDNESDAY 15th MARCH 2017 DOWNLOAD FESTIVAL TAG TEAMS WITH WWE NXT THIS SUMMER NXT SUPERSTARS BOBBY ROODE, ALEISTER BLACK, ASUKA, TYE DILLINGER, KASSIUS OHNO, ERIC YOUNG, ALEXANDER WOLFE, KILLIAN DAIN AND NIKKI CROSS SET TO APPEAR PLUS MANY MORE TO BE ANNOUNCED www.downloadfestival.co.uk Download Festival, the undisputed champion of rock and metal, has today announced the grand return of WWE NXT LIVE! to the hallowed grounds of Donington Park. Music fans will once again be electrified with incredible displays of skill and athleticism, as the hugest names in Sports Entertainment deliver the complete WWE NXT experience alongside the world’s biggest rock stars, on June 9 - 11. Tickets are available now from downloadfestival.co.uk/tickets. Alongside headliners System Of A Down, Biffy Clyro and Aerosmith, fans can catch NXT Superstars *Bobby Roode, Aleister Black, Tye Dillinger, Kassius Ohno, Eric Young, Alexander Wolfe, Killian Dain, Nikki Cross and many more as they bring the hard-hitting, innovative and action packed brand of NXT to the purpose built, full scale ring in the main festival arena. Last year saw NXT make a huge impact with Download fans, delivering a weekend of action to capacity crowds with shocking debuts, high flying manoeuvres and surprising returns from the biggest names in sports entertainment. It also provided one of the most touching moments in Download history when Executive Vice President of Talent, Live Events & Creative and WWE icon Triple H was awarded the Metal Hammer ‘Spirit Of Lemmy’ award on the main stage, in honour of his relationship with the late legendary Motörhead frontman Lemmy Kilmister and to acknowledge the affinity between the rock and wrestling worlds. -

Order Form Full

METAL ARTIST TITLE LABEL RETAIL 1349 MASSIVE CAULDRON OF CHAOS (SPLATTER SEASON OF MIST RM121.00 16 LIFESPAN OF A MOTH RELAPSE RM111.00 16 LOST TRACTS OF TIME (COLOR) LAST HURRAH RM110.00 3 INCHES OF BLOOD BATTLECRY UNDER A WINTERSUN WAR ON MUSIC RM102.00 3 INCHES OF BLOOD HERE WAITS THY DOOM WAR ON MUSIC RM113.00 ACID WITCH MIDNIGHT MOVIES HELLS HEADBANGER RM110.00 ACROSS TUNDRAS DARK SONGS OF THE PRAIRIE KREATION RM96.00 ACT OF DEFIANCE BIRTH & THE BURIAL (180 GR) METAL BLADE RM147.00 ADMIRAL SIR CLOUDESLEY SHOVELL KEEP IT GREASY! (180 GR) RISE ABOVE RM149.00 ADMIRAL SIR CLOUDSLEY SHOVELL CHECK 'EM BEFORE YOU WRECK 'EM RISE ABOVE RM149.00 AGORAPHOBIC NOSEBLEED FROZEN CORPSE STUFFED WITH DOPE RELAPSE RECORDS RM111.00 AILS THE UNRAVELING FLENSER RM112.00 AIRBOURNE BLACK DOG BARKING ROADRUNNER RM182.00 ALDEBARAN FROM FORGOTTEN TOMBS KREATION RM101.00 ALL OUT WAR FOR THOSE WHO WERE CRUCIFIED VICTORY RECORDS RM101.00 ALL PIGS MUST DIE NOTHING VIOLATES THIS NATURE SOUTHERN LORD RM101.00 ALL THAT REMAINS MADNESS RAZOR & TIE RM138.00 ALTAR EGO ART COSMIC KEY CREATIONS RM119.00 ALTAR YOUTH AGAINST CHRIST COSMIC KEY CREATIONS RM123.00 AMEBIX MONOLITH (180 GR) BACK ON BLACK RM141.00 AMEBIX SONIC MASS EASY ACTION RM129.00 AMENRA ALIVE CONSOULING SOUND RM139.00 AMENRA MASS I CONSOULING SOUND RM122.00 AMENRA MASS II CONSOULING SOUND RM122.00 AMERICAN HERITAGE SEDENTARY (180 GR CLEAR) GRANITE HOUSE RM98.00 AMORT WINTER TALES KREATION RM101.00 ANAAL NATHRAKH IN THE CONSTELLATION OF THE.. (PIC) BLACK SLEEVES RM128.00 ANCIENT VVISDOM SACRIFICIAL MAGIC -

Black Svan Are a 5-Piece Metal Band from Ireland, Formed in 2009

Bio Black Svan are a 5-Piece Metal band from Ireland, formed in 2009. Drawing on many influences including Metallica, Alice In Chains, Black Sabbath, Pantera and Mastodon the band fuses groove laden, hard hitting riffs with powerful vocals and pounding drums. The most notable successes to date include a 2010 European Tour supporting Fozzy and Stuck Mojo. The tour included dates in France, Spain, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Czech Republic and Hungary. During this run the band gained many fans and also some invaluable experience which added to their already very professional approach. Most recently the band have released their debut album ‘16 Minutes’, via M&O Music. The album was mixed and mastered by Jacob Hansen (Volbeat, Doro, Amaranthe) at Hansen Studios in Denmark. ‘16 Minutes’ is a powerful yet melodic album which shows off the bands songwriting at its best. Since its release, ‘16 Minutes’ has peaked at no. 2 in the iTunes Metal Chart in Ireland. The band are currently making plans to tour in 2015! Review Snippets FrenchMetal.com - 18/20 “Black Svan have found their own style and deliver a blasting album!” MetalIreland.com - 4.2/5 “ There’s no question about it. This is huge. It sounds huge, feels huge and is clearly the work of a band who either should be, or soon will be, huge.” MusiqueAlliance.fr - 4.5/5 “An essential album” Soil Chronicles - “The acquisition of this album becomes almost an obligation” Two Guys Metal Reviews - “If you want something modern, fun and catchy then this is the record for you. -

Wwe/Wwf Wrestling Trivia Quiz

WWE/WWF WRESTLING TRIVIA QUIZ ( www.TriviaChamp.com ) 1> Which wrestler left the WWE to join the UFC, during which he won the UFC Heavyweight Championship, then returned to the WWE in April 2012? 2> Who was the first inductee into the WWE Hall of Fame? 3> Which of the following is not a persona under which Mick Foley has wrestled - Dude Love, Psicosis or Mankind? 4> Stephanie McMahon, daughter of WWE Chairman Vince McMahon, married which wrestler in 2003? 5> Who was the host of "The Highlight Reel"? 6> Ooh yeah! Which wrestler who died aged 58 in 2011 formed The Mega Powers tag team with Hulk Hogan, then dropped the WWF title to Hogan at Wrestlemania V? 7> In 1989 Hulk Hogan starred in the movie No Holds Barred, in which he wrestled a character played by Tommy Lister. What was the character's name? 8> Who won an unprecedented 10th WWE Championship at Night of Champions on September 18, 2011? 9> The son of Paul Bearer and brother of Kane, which WWE Superstar achieved a 20-0 record at Wrestlemania after defeating Triple H at Wrestlemania 28? 10> Which female cast member of Jersey Shore wrestled in a 6-person mixed tag team match at Wrestlemania 27? Answers: 1> Brock Lesnar - Lesnar became the youngest WWE Champion at age 25. 2> Andre the Giant - Known as the 'Eighth Wonder of the World', Andre's death was the reason for the creation of the Hall of Fame in 1993. 3> Psicosis - Cactus Jack is the third well-known persona of Foley. -

CEE Legal Matters

PRELIMINARY MATTERS JULY 2020 Year 7, Issue 6 CEE July 2020 Legal Matters In-Depth Analysis of the News and Newsmakers That Shape Europe’s Emerging Legal Markets Guest Editorial: Victor Gugushev of Gugushev & Partners Featured Deals Across the Wire: Deals and Cases in CEE On the Move: New Firms and Practices The Buzz in CEE Article: Greece Plays the Long Game Inside Insight: Interview with Andras Busch of Siemens Energy Hungary Article: Rebuilding and Reshaping in the Aftermath of COVID-19 The Confident Counsel: Online Presenting – Connecting During COVID-19 Market Spotlight: Romania Guest Editorial: Francisc Peli of PeliPartners Article: Clear for Take-Off: (No) Sexism in Romanian Law Firms Inside Insight: Interview with Florina Homeghiu of Policolor-Orgachim Inside Insight: Interview with Madalina Juncu of Mondelez Market Snapshots Inside Out: RCS & RCS / Digi Communications Bond Issuances Expat on the Market: Interview with Simon Dayes of Dentons Market Spotlight: Moldova CEE LEGAL MATTERSGuest Editorial by Igor Odobescu of ACI Partners Article: The Funambulists Experts Review: Energy 1 JULY 2020 DEALER’S CHOICE LAW FIRM SUMMITPRELIMINARY MATTERS & 2020 CEE DEAL OF THE YEAR AWARDS OCTOBER 13, 2020 CEE/YOU IN LONDON! DEALER’S CHOICE SUMMIT CO-HOSTED BY: SPONSORED BY: REGIONAL SPONSOR BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA BULGARIA SPONSOR SPONSOR CROATIA SPONSOR HUNGARY SPONSOR MONTENEGRO SPONSOR ROMANIA SPONSOR UKRAINE SPONSOR 2 CEE LEGAL MATTERS PRELIMINARY MATTERS JULY 2020 EDITORIAL: IT AIN’T ALWAYS EASY By David Stuckey A few weeks ago we got what seemed to be a reliable message the ability to publish the story first. Both that a well-known firm with a presence across the region had times, those promises were forgotten, closed one of its CEE offices.