FROM BLUEPRINT to BUILDING Lifting the Torch for Multilingual Students in New York State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PRO BONO NEWS July 2015

PRO BONO NEWS JULY 2015 Why Pro Bono Matters IN THIS ISSUE SOMETIMES, PRO BONO WORK offers an opportunity to make a profound Click on an article to jump to it. difference in an individual’s or family’s life, such as by helping a veteran Proud to Help Lead the Fight obtain long-overdue disability benefits, or securing asylum for a family for Marriage Equality fleeing persecution. page 2 In other instances, pro bono service can bring lasting benefits to Resolution of New York thousands, hundreds of thousands or even millions of people. Recently, City Jails Reform Case a Ropes & Gray was privileged to play a key role in three pro bono matters Pro Bono Victory with that kind of sweeping social impact. page 2 In April, Douglas Hallward-Driemeier, head of the firm’s appellate & Supreme Court practice, argued before the Supreme Court on behalf of the plaintiffs in the landmark Public Service Honored at marriage equality case that has just given our LGBT friends, family members, neighbors 12th Annual Pro Bono Awards and their families a right that should have been theirs all along. The court’s June 26 decision page 3 will go down in history with other iconic civil rights milestones and will benefit an untold Q&A: Securing Voting Rights number of people in the years to come. in Massachusetts A few days earlier in June, the resolution of a class-action lawsuit alleging a pattern and page 4 practice of excessive force against inmates at Rikers Island and other New York City jails, in violation of their Eighth Amendment rights, capped one of the firm’s most significantpro New Associates Embrace bono matters. -

United States District Court District of Connecticut

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF CONNECTICUT DAVID TUTTLE, Plaintiff, v. No. 3:17-cv-1507 (JAM) SCOTT SEMPLE, et al., Defendants. INITIAL REVIEW ORDER Plaintiff David Tuttle has filed this pro se complaint that principally alleges a violation of his rights under the Eighth Amendment while he was subject to solitary confinement for about one year at the Northern Correctional Institution in Connecticut. I think it is likely that defendants have qualified immunity, but rather than summarily dismissing the complaint at this time I will allow it to be served on defendants while also allowing plaintiff to file an amended complaint within 30 days if he believes that there are additional facts that would suffice to withstand a motion to dismiss on grounds of qualified immunity. BACKGROUND Plaintiff has filed this lawsuit against the Connecticut Department of Correction’s Commissioner Scott Semple, Warden Nick Rodriguez, Health Services Administrator Brian Liedel, Dr. Mark Frayne, and Dr. Gerard Gagne. Plaintiff sues each of these defendants for money damages in their personal and official capacity, and plaintiff also seeks injunctive relief. The following facts are assumed to be true solely for purposes of my initial evaluation of the adequacy of the allegations in the second amended complaint. Plaintiff was originally convicted and sentenced in Massachusetts before being transferred in 2012 to Connecticut in accordance with an arrangement under an interstate corrections compact. In late January 2017, 1 he was transferred from the Corrigan -

Gonsalves Declaration

Case 3:20-cv-00540-SRU Document 12-5 Filed 04/22/20 Page 1 of 22 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF CONNECTICUT ____________________________________ ) DAVID TERWILLIGER, ) ) Petitioner, ) ) v. ) ) No. 3:20-cv-540 ROLLIN COOK, Commissioner, ) Connecticut Department of Correction, and ) NICK RODRIGUEZ, Warden, Osborn ) April 22, 2020 Correctional Institution, ) ) Respondents. ) ____________________________________) DECLARATION OF GREGG S. GONSALVES I, Gregg S. Gonsalves, upon my personal knowledge, and in accordance with 28 U.S.C. § 1746, declare as follows: 1. I am an epidemiologist at the Yale School of Medicine and School of Public Health. I have worked at the schools of medicine and public health since 2017. Attached as Exhibit A is my CV. 2. COVID-19 is an infectious disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), a virus closely related to the SARS virus. In its least serious form, COVID-19 can cause illness including fever, cough, and shortness of breath. However, for individuals who become more seriously ill, a common complication is bilateral interstitial pneumonia, which causes partial or total collapse of the lung alveoli, making it difficult or impossible for patients to breathe. Thousands of patients have required hospital-grade respirators, and COVID-19 can progress from a fever to life-threatening pneumonia with what are known as “ground-glass opacities,” a lung abnormality that inhibits breathing. 3. In about 16% of cases of COVID-19, illness is severe including pneumonia with respiratory failure, septic shock, multi organ failure, and even death. 4. Certain populations of people are at particular risk of contracting severe cases of COVID- 19. -

RFA Summit & State Education Fellowship Convening Agenda

RFA Summit & State Education Fellowship Convening Agenda October 2-4, 2019 Eaton Hotel,1201 K Street, NW, Washington, DC Contents Convening At-A-Glance……………………………………….………………………………..2 State Education Fellowship Convening Agenda………………………………...………….. 3 Convening Logistics………………………………………………………...…………………..9 Contact Information…………………………………………………………….……………...14 Speaker Biographies…………………………………………………………………………..20 Convening At-A-Glance Date Agenda Item Start Time Location Welcome 5:30 PM Wild Days Wednesday, Reception Eaton Hotel Rooftop October 2 1201 K Street NW Washington, DC 20005 Breakfast 8:00 AM Salon (2nd Floor) Eaton Hotel 1201 K Street NW Washington, DC 20005 2019 Summit What 8:45 AM Beverly Snow Ballroom (2nd Floor) Works to Advance Eaton Hotel Economic Mobility 1201 K Street NW Washington, DC 20005 Lunch - The Story 12:00 PM Beverly Snow Ballroom (2nd Floor) of Economic Eaton Hotel Mobility in America 1201 K Street NW Washington, DC 20005 Thursday, October 3 Concurrent 2:15 PM Various - See Summit Agenda Workshops State Education 6:30 PM Ghibellina Agency & 1610 14th St NW Workforce Washington, DC 20009 Reception and Dinner Breakfast & 8:00 AM Salon (2nd Floor) State Standard of Eaton Hotel Excellence Launch 1201 K Street NW Event Washington, DC 20005 Friday, State Education 9:45 AM Crystal Room (1st Floor) October 4 Agency Fellowship Eaton Hotel Convening 1201 K Street NW Washington, DC 20005 Adjourn 3:30 PM Travel to airport Please see transportation details below 2 Results for America Summit 2019 & State Education Fellowship Convening Agenda October 2-4, 2019 Eaton Hotel, 1201 K Street, NW, Washington, DC 20005 Wednesday, October 2, 2019 5:30 - 7:30 pm Welcome Reception Eaton Hotel Rooftop - Wild Days Note: There will not be a formal Fellows dinner this evening. -

2016-17 NORTH TEXAS MEN's GOLF Men's Golf

2016-17 NORTH TEXAS MEN'S GOLF FACT AND RECORDS BOOK men's golf North Texas Athletics Department 1301 S. Bonnie Brae Denton, TX 76207 Office: (940) 565-2662 Shipping Address - Use this for overnight - FED EX / UPS 1251 South Bonnie Brae Shipping Dock Denton, TX 76207 Mailing Address - US Postal Service ONLY 1155 Union Circle #311397 Denton, TX 76203 www.meangreensports.com Credits: the North Texas Media Relations Department Photography: Rick Yeatts Mean Green Mission Statement * To Promote and monitor the educational achievement and personal growth of student-athletes, emphasizing that their education- al growth and development is the primary purpose of intercollegiate athletics * To conduct an athletics program that protects and enhances the physical and educational welfare of student-athletes * To provide fair and equitable opportunity for all student-athletes and staff participating in intercollegiate sport activities, regard- less of gender or ethnicity * To promote the principles of good sportsmanship and honesty in compliance with the University of North Texas, state, NCAA and conference regulations * To conduct a competitive athletics program that promotes faculty, staff, student and community affiliation with the University of North Texas * To serve the community through public service and outreach activities which positively reflect on the University of North Texas and promote good will in the community. TABLE OF CONTENTS Men’s Golf Quick Facts 2 PROFILES University Information Head Coach .................................................. -

The Ethics Corner First We Get You Through Law School

Year 2000: We'reHere.NowWhat? The ethics Corner First We Get You Through Law School. .. Then We Get You Through The Bar Exam! Gilbert Law Summaries Legalines Over 4 Million Copies Sold BAR/BRI Bar Review Relied On By Over 500,000 Lawyers ©rJJ!Jbr1 GROUP Our Only Mission Is Test Preparation Call Toll Free 1-888-3BARBRI or visit our web site at http.//www.barbri.com Juris Vol. 33, No. 1 • Winter 1999 You are young, my son, and as the years Staff go by, time will change and even reverse Editor-in-Chief many of your present opinions. Nick Rodriguez-Cayro Refrain therefore awhile from setting yourself Executive Editor up as a judge of the highest matters. Maureen Jordan Plato Managing Editor Matthew Clark • Senior Editor In thisISsue Gianni Floro Production Editor Maureen McQuillan Editorial: A Word from the Weary Assistant Executive Editors by Nick Rodriguez-Cayro ............ ... ................................................. .... ......... pg. 2 Annary Aytch Julie Gentry Repressed Memory and False Memory Syndrome: Nancy Koerbel Current Scien tific and Legal Perspectives Christi Neroni by Douglas Harhai ........... .................... ......... .. .............................................. pg. 3 Assistant Senior Editors Leslie Britton The Internet and the First Amendment: Douglas Harhai Bridgett Langer Regulations and Standards by Eliana Carrelli .................... .............................................. ................... ... pg. 10 Assistant Managing Editors Leah Lewandowski Patrick Dougherty The ABCs of Avoiding Malpractice -

West Virginia Power Game Notes

WEST VIRGINIA POWER GAME NOTES South Atlantic League - Class-A affiliate of the Seattle Mariners since 2019 - 601 Morris St. Suite 201- Charleston, WV 25301 - 304-344-2287 - www.wvpower.com - Media Contact: David Kahn WEST VIRGINIA POWER (25-26, 62-59) at DELMARVA SHOREBIRDS (32-18, 80-39) Game: 122 (Road: 63 [30-32]) | August 14, 2019 | Arthur W. Perdue Stadium | Salisbury, Md. Radio: The Jock 1300 and 1340 AM - wvpower.com Airtime: 6:45 P.M. THE PITCHING MATCH-UP: RHP Devin Sweet (7-4, 2.89 ERA) vs. RHP Gray Fenter (6-2, 1.88 ERA) Sweet: Has won his last four decisions dating back to July 6 at Lexington Fenter: Boasts a 1.50 ERA in two games (one start) vs. WV; Has tossed 6 IP with 11 K and 0 BB POWER FALLS IN BACK-AND-FORTH AFFAIR 10-9: Julio Rodriguez smacked his first career grand slam and CURRENT ROAD TRIP tallied a career-high six RBI, but West Virginia dropped the middle match of their series with the Delmarva Shorebirds, Record: 4-2 Season Highs 10-9, Tuesday evening at Arthur W. Perdue Stadium. The Power got on the board first in the opening frame, as Ryan Batting Statistics Batting Statistics: Ramiz and Matt Sanders started the ballgame with back-to-back singles before Austin Shenton brought in a run on AVG: .228 (46-for-202) AVG: .362 (25-for-69) a groundout later in the stanza to make it 1-0. Delmarva answered immediately in the home half, taking advantage AB: 202 AB: 248 of a shaky Ryne Inman, who only lasted two-thirds of an inning and gave up three runs on one hit and five walks. -

Overall Defensive Stats File:///C:/Daktronics/Dakstats Football/Sdefense 1.Html

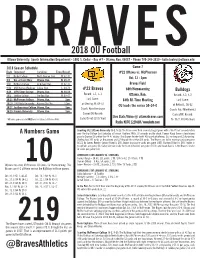

BRAVES2018 OU Football Ottawa University® Sports Information Department - 1001 S. Cedar - Box #7 - Ottawa, Kan. 66067 - Phone 785-248-2610 - [email protected] 2018 Season Schedule Game 7 Date Opponent Location Time/Result #22 Ottawa vs. McPherson 9/1 Bethel College North Newton, Kan. W, 42-12 Oct. 13 - 1pm 9/8 Uni. of Saint Mary Ottawa, Kan. W, 29-27 9/15 Bethany College Lindsborg, Kan. W, 42-35 Braves Field 9/22 #14 Kansas Wesleyan Salina, Kan. L, 24-70 #22 Braves 88th Homecoming 9/29 #RV Tabor College Ottawa, Kan. W, 34-14 Bulldogs Record: 5-1, 5-1 10/6 Sterling College Sterling, Kan. W, 48-47 Ottawa, Kan. Record: 3-2, 3-2 10/13 McPherson College Ottawa, Kan. 1pm Last Game: 84th All-Time Meeting Last Game: 10/20 #RV Avila University Kansas City, Mo. 12pm at Sterling, W, 48-47 OU leads the series 59-24-0 at Bethel L, 56-42 10/27 Southwestern College Ottawa, Kan. 1pm Coach: Kent Kessinger Coach: Paul Mierkiewicz 10/10 Friends University Ottawa, Kan. 1pm Career/OU Record: Career/MC Record: Live Stats/Video @ ottawabraves.com *All home games are in BOLD and are played at Braves Field Same/93-65 (15th Year) 76-93/7-30 (4th Year) Radio: KOFO 1220 AM / www.kofo.com Scouting #22 Ottawa University (5-1, 5-1): The Braves won their second straight game with a 48-47 last second victory A Numbers Game over Sterling College last Saturday at Smisor Stadium. With 1.8 seconds on the clock, Connor Kaegi threw a touchdown pass to Darrion Dillard for the 48-47 victory. -

Killingly & Its Villages Vol

Mailed free to requesting homes in Brooklyn, the borough of Danielson, Killingly & its villages Vol. VIII, No. 10 Complimentary home delivery (860) 928-1818/email:[email protected] Friday, January 17, 2014 THIS WEEK’S QUOTE CL&P shows off new strategies to local officials “This time, like ‘WHEN A STORM IS ROLLING IN, WE NEED TO BE PREPARED’ all times, is a very BY JASON BLEAU informed on the company’s efforts to and frustration. good one, if we but VILLAGER STAFF WRITER better serve its customers following a Johnston revealed that there is a know what to do THOMPSON — In 2011, dramatic weather event. very extensive response plan that with it.” Connecticut Light & Power came The most recent major storm CL&P CL&P follows that their customer under fire for a slow response after has had to respond to was Tropical may not be aware of, which sets prior- several storms, including an October Storm Sandy in October of 2012, an ities following a significant weather Ralph Waldo Emerson snowstorm, knocked out power to incident that resulted in half a mil- situation. many throughout the state. lion customers without power, 105 It all starts before a storm even hits Today, CL&P is continuing efforts miles of cable replacement, 1,700 util- the state. to avert a disaster like what occurred ity pole replacements and 2,100 trans- “Days out, one thing our company INSIDE in 2011 by making improvements to formers that needed to be replaced as does is weather watch,” Johnston respond faster and more efficiently to well. -

Promotions and Reassignments from the Commissioner

Our Mission The Department of Correction shall strive to be a global leader in progressive correctional practices and partnered re-entry initiatives to support responsive evidence-based practices aligned to law-abiding and accountable behaviors. Safety and security shall be a priority component of this responsibility as it pertains to staff, victims, citizens and offenders. From the Commissioner February 15, 2019 Since I agreed to accept Governor Lamont’s gracious offer through to be the Commissioner of this amazing agency, I can truly April 18, 2019 relate to the frequently quoted saying by an ancient Greek philosopher that “the only thing that is constant is change.” There certainly has been a great deal of change recently among Distributed bimonthly the leadership of the Department of Correction. Starting to 5,500 staff with myself as the new Commissioner, to a new Deputy Commissioner of Operations, to two new Directors (one for and via the Internet Programs and Treatment, and one for Parole and Community Services), two throughout Connecticut new District Administrators, five new Wardens, and eight Wardens reassigned and the nation to different facilities. by the I feel it is important to point out that even though many of these individuals are Department of Correction “new” to their positions, they can hardly be considered new to the agency. In 24 Wolcott Hill Road fact, several of these individuals literally have decades of experience working for the Department of Correction. They will certainly bring an informed Wethersfield, CT 06109 perspective to their new roles. see Change for the Better/page 2 Promotions and Reassignments Ned Lamont Governor Commissioner Rollin Cook is pleased to announce the following promotions and reassignments. -

HSDA Virtual Conference Agenda

HISPANIC STUDENT DENTAL ASSOCIATION V I R T U A L S T U D E N T R E G I O N A L 2 0 2 0 A G E N D A S E P T E M B E R 2 6 • 1 2 - 2 : 3 0 P M E S T 12:00 - 12:15 PM Opening Remarks Edwin A. del Valle-Sepulveda, DMD, JD HDA President Sarita Arteaga, DMD, MA, MAGD HDA Foundation President Mark S. Wolff, DDS, PhD Morton Amsterdam Dean, Penn Dental Medicine 12:15 - 12:45 PM Penn Dental Faculty Karina Hariton-Gross, DDS, DMD "Navigating Dentistry as a Minority" Julián Conejo, DDS, MSc "Highly Esthetic Ceramic Restorations with CEREC: An update on the latest materials, software and hardware for 2021" 12:45 - 1:15 PM Scholarship Ceremony Pt. I Moderator: Dr. Sarita Arteaga Matilde Hernández González, DDS, MS Remarks Nick Rodriguez, DDS, MPH Past Recipient of Colgate Dental Student & Resident Scholarships Sarita Arteaga, DMD, MA, MAGD Announcement of 10 Colgate Scholarship Recipients 1:15 - 1:45 PM HDA Panel - Alternative Careers in Dentistry Moderator: Dr. Manuel A. Cordero Timothy L. Ricks, DMD, MPH, FICD "Public Health & Military" Rosa Chaviano-Moran, DMD, FICD "Academia" Gene Romo, Jr, DDS "General Dentist & Group Practice" Tyrone Fernando Rodriguez, BS, DDS, FAAPD, FACD "Specialist" HISPANIC STUDENT DENTAL ASSOCIATION V I R T U A L S T U D E N T R E G I O N A L 2 0 2 0 A G E N D A S E P T E M B E R 2 6 • 1 2 - 2 : 3 0 P M E S T 1:45 - 2:15 PM Scholarship Ceremony Pt. -

Inside Collegiate BASEBALL

Collegiate Baseball The Voice Of Amateur Baseball Started In 1958 At The Request Of Our Nation’s Baseball Coaches Vol. 63, No. 2 Friday, Jan. 24, 2020 $4.00 Innovative Products Win Top Awards Nine special inventions 2020 Winners are tremendous advances for game of baseball. Best Of Show By LOU PAVLOVICH, JR. Editor/Collegiate Baseball Awarded By Collegiate Baseball F n u io n t c a t ASHVILLE, Tenn. — Nine i v o o n n a innovative products at the recent n l I i t y American Baseball Coaches N Association Convention trade show in Nashville were awarded Best of Show B u certificates by Collegiate Baseball. i l y t t i T v o There were 61 nominations submitted i t L a a e r s t C to Collegiate Baseball for the contest which showcases the top new baseball products of 2019. The 76th ABCA Convention featured a record 365 companies that exhibited their products. Now in its 21st year, the Best of Show awards encompass a wide variety of concepts and applications that are new to baseball. REMARKABLE PRODUCT — Always Grind Baseball Notebooks are one of nine exciting inventions that have been awarded Best of Show certificates by Nashville ABCA Convention See BEST OF SHOW , Page 4 Collegiate Baseball. From left to right is Colby Wright and Joe Moroney. Combined 862 Coaches, Players Tossed During 2019 Season NCAA Ejections Rise For 5th Consecutive Year Over the past 3 • 2015: 658 total ejections. 124 player and 42 assistant coach The biggest one-year jump ejections took place.