Generic Use of the Second Person Pronoun in Danish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VEST Uddannelse Job-1.Xlsx

Deltagerliste*VEST:*Uddannelse/Job*D*2.*Juni*2014 Anders'Ladegaard [email protected] UU'DANMARK Anders'Skov [email protected] UU'Aarhus'Samsø Anne?Me@e'Almind'Andersen anne?me@e@uu?lillebaelt.dk UU'Lillebælt Bente'Sønderup [email protected] Ungeenheden'Herning BeGna'Dichmann beGna@uu?lillebaelt.dk UU'Lillebælt Birgit'Petersen [email protected] UU'Odder'Skanderborg BJarne'Jeppesen bJarne@uu?lillebaelt.dk UU'Lillebælt Bri@'Bitsch [email protected]@svendborg.dk UU'Center'Sydfyn Charlo@e'Aalbæk'Hansen charlo@e@uu?lillebaelt.dk UU'Lillebælt Dorien'Hansen dorien@uu?lillebaelt.dk UU'Lillebælt Elin'Holst [email protected] UU'Aalborg Erik'Lykkegaard erik@uu?lillebaelt.dk UU'Lillebælt Eva'Geer [email protected] UU'Aarhus'Samsø Eva'Sherson [email protected] UU'Odder'Skanderborg Gurli'Nyborg'Mogensen gurli@uu?lillebaelt.dk UU'Lillebælt Hanne'Skov'ChrisPansen [email protected] UU'Center'Sydfyn Henrik'Michael'Nielsen [email protected] UU'Varde/Team'Ung'i'Uddannelse Henry'Hansen [email protected] UU'Skive Iben'Bak'Larsen [email protected] UU'Odder'Skanderborg Jens'Oluf'Bundgaard [email protected] UU'Aalborg Jens'Seifert'Baier'Andersen [email protected]'Randers Jens'Søndergaard'Nielsen [email protected] UU'Ringkøbing'FJord John'A.'Hansen [email protected] UU'Odder'Skanderborg Jørgen'Danielsen [email protected] UU'Odder'Skanderborg Jørgen'Krogh'Poulsen [email protected] UU?Herning Jørn'Tollef'Dresler [email protected] UU'Center'Sydfyn karen'dinesen -

RUTE 11 OG RUTE 24 ESBJERG - TØNDER Forundersøgelse >>> Opgradering Af Vejforbindelsen Esbjerg - Grænsen

RUTE 11 OG RUTE 24 ESBJERG - TØNDER Forundersøgelse >>> Opgradering af vejforbindelsen Esbjerg - grænsen RAPPORT 425 - 2012 RUTE 11 ESBJERG - TØNDER Forundersøgelse >>> Opgradering af vejforbindelsen Esbjerg - Grænsen Rapport 425 - 2012 REDAKTION: OPLAG: Vejdirektoratet xxx DATO: TRYK: November 2012 Vejdirektoratet LAYOUT: ISBN (NET): Vejdirektoratet 9788770607162 FOTOS: ISBN: Vejdirektoratet 9788770607148 GRUNDKORT: COPYRIGHT: © Copyright Kort- og Matrikelstyrelsen Vejdirektoratet, 2012 INDHOLD 1. INDLEDNING 5 2. SAMMENFATNING 6 3. EKSISTERENDE FORHOLD 10 4. ANDRE PLANINITIATIVER 16 5. ERHVERVSFORHOLD 18 6. LØSNINGSFORSLAG 22 7. TRAFIKALE KONSEKVENSER 28 8. AREALBEHOV 34 9. PLAN- OG MILJØFORHOLD 36 10. ANLÆGSOVERSLAG OG SAMFUNDSØKONOMI 48 E20 E20 VEJEN BRAMMING ESBJERG 11 24 32 Gredstedbro FANØ 32 RIBE 24 Gram MANDØ 11 VADEHAVET Rejsby 25 Toftlund Arrild Skærbæk RØMØ 25 11 Løgumkloster Bredebro Abild Møgeltønder Tinglev TØNDER 8 Rute 11 Rute 24 FIGUR 1.1 Undersøgelsesstrækningen 1. INDLEDNING INDLEDNING Det fremgår af aftalen om ”Bedre mobilitet”, af 26. novem- ber 2010, at der skal gennemføres en forundersøgelse af mulighederne for udbygning af strækningen mellem Esbjerg ”Bedre mobilitet” er en aftale af 26. november 2010 mellem og Tønder. regeringen (Socialdemokraterne, Det Radikale Venstre og Socialistisk Folkeparti), Venstre, Dansk Folkeparti, Liberal Alliance og Det Konservative Folkeparti. Undersøgelsen skal omfatte rute 11 mellem E20, Esbjerg- motorvejen ved Korskro og den dansk - tyske grænse syd for Tønder, en strækning på ca. 77 km. Endvidere skal rute 24 mellem Gredstedbro og Esbjerg inddrages i undersøgelsen. Denne strækning er ca. 13 km. Strækningerne er vist på figur 1.1. Forundersøgelsen skal belyse behov og muligheder for op- gradering af rute 11 samt af rute 24, ligesom undersøgelsen skal belyse de væsentligste konsekvenser i forhold til trafik, miljø og økonomi. -

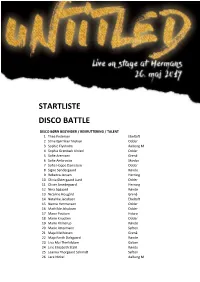

Startliste Disco Battle

d STARTLISTE DISCO BATTLE DISCO BØRN BEGYNDER / REKRUTTERING / TALENT 1 Thea Pedersen Ebeltoft 2 Stine Bjørnkær Nielsen Odder 3 Sophie Flyvholm Aalborg M 4 Sophia Grønbæk Ulsted Odder 5 Sofie Arentzen Grenå 6 Sofie Ambrosius Skovby 7 Sofia Hoppe Danielsen Odder 8 Signe Søndergaard Rønde 9 Rebecca Jensen Herning 10 Olivia Østergaard Lund Odder 11 Oliver Smedegaard Herning 12 Nina Søgaard Rønde 13 Nicoline Hougård Grenå 14 Natahlie Jacobsen Ebeltoft 15 Nanna Hermansen Odder 16 Mathilde Jakobsen Odder 17 Marie Poulsen Hobro 18 Marie Knudsen Odder 19 Marie Flinterup Rønde 20 Marie Attermann Søften 21 Maja Mathiesen Grenå 22 Maja Fanth Dalsgaard Rønde 23 Liva Mai Therkildsen Galten 24 Line Elisabeth Stahl Rønde 25 Leanna Thorgaard Schmidt Søften 26 Lara Nickel Aalborg M 1 27 Katrine Høj Kristensen Rønde 28 Josefine Hoier Galten 29 Johanne Nybye Michell Odder 30 Ida Kauffeldt Søften 31 Frida Houlberg Ballerup 32 Frida Hansen Aalborg M 33 Emma Erland Therry Odder 34 Emilie Laursen Herning 35 Emilie Jensen Odder 36 Emilia Warming Odder 37 Elise Toftelund Søften 38 Clara-Amalie Koefoed Aarhus V 39 Celine Christoffersen Skovby 40 Carla Hededam Vangsgaard Odder 41 Ashley Horley Aalborg M BØRN KONKURRENCE / SUPERKONKURRENCE 42 Regitze Andersen Hatting GT 43 Mikkeline Jagd Niekrenz Rønde 44 Mia Christensen Hatting GT 45 Klara Nygaard Ballerup 46 Karoline Mathilde Zappe Skanderborg 47 Ida Haulrik-Friis Rønde 48 Emma Bruun Rønde 49 Amanda Degn Hatting GT 50 Alida Christensen Rønde BØRN STAR / SUPERSTAR 109 Olivia Obiefule Viborg JUNIOR BEGYNDER / REKRUTTERING / TALENT 51 Thilde Hougaard Grenå 52 Sophia Vangsgaard Aalborg PH 53 Silje Gundestrup Odder 54 Ninna Vinter Bruhn Odder 55 Melina Sølvhøj Ballerup 56 Mathilde Dam Nybye Odder 57 Liv Dahl Schou Aalborg PH 58 Lina Rasmusssen Køge B. -

Water in Figures 2019

WATER IN FIGURES 2019 DANVA STATISTICS & BENCHMARKING Denmark LEADER TEXT: CARL-EMIL LARSEN/ PHOTO: DANVA Wastewater heat pumps take heat production to a new level ater companies act efficiently and expenses. The total annual cost of drinking related to last year's hot summer in Denmark, create value for households and in- water and wastewater is € 771 for an average when the water companies experienced more W dustry. This document shows the family. The average water price has increased ruptures than usual as a result of the soil being water sector's key figures compiled by DANVA by only 0.94% from € 9.23 to € 9.32. It is less affected by the heat and creating more stress in “Water in figures 2019”. We will also review than the general net price trend for society as around the water pipes that caused several relevant topics including how water compa- a whole, which from 2017 to 2018 increased ruptures and resulted in water loss. nies are starting to use water as hydroelectric by more than 1%. The key figures also show that Danes have power plants to generate CO2-neutral energy, Moreover, the small change in the price access to tap water almost 24 hours a day, 365 which benefit consumers and the Danish cli- trend has to be seen in the context of the im- days of the year. Danes, on average, are without mate change plan. plementation of the "Three-Step Tariffs Model”, access to water for only 35 minutes out of the For example, Kalundborg Forsyning's new which led to cheaper wastewater prices for large 525,600 minutes in the year, which means they heat pumps pull heat out of the wastewater, consumers, and was during 2018 fully phased have access to water 99.99% of the time. -

The Local Government Reform – in Brief

THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT REFORM – IN BRIEF Published by: The Ministry of the Interior and Health Department of Economics Slotsholmsgade 10-12 DK-1216 Copenhagen K Telephone: +45 72 26 90 00 Telefax: +45 72 26 90 01 E-post: [email protected] Homepage: www.im.dk Design: 1508 A/S Photo: Manipulation.as Print: SaloGruppen A/S Impression: 10,000 Price: free ISBN-no. (publication – Danish version): 87-7601-149-6 ISBN-no. (electronic – Danish version): 87-7601-151-8 ISBN-no. (publication – English version): 87-7601-152-6 ISBN-no. (electronic – English version): 87-7601-153-4 You can order the publication at: NBC Ekspedition Telephon: +45 56 36 40 48 Telefax: +45 56 36 40 39 E-mail: [email protected] Telephone opening hours: Monday-Thursday 9.30 a.m.- 4 p.m., Friday 9.30 a.m. - 3 p.m. The publication is available on the internet at the homepage of the Ministry of the Interior and Health (www.im.dk). Contents Contents...............................................................................................................................3 Preamble..............................................................................................................................4 Chapter 2 A New Map of Denmark ...................................................................................13 Chapter 3 Who will be doing what in the Public Sector? ...................................................22 Chapter 4 Public Economy after the Local Government Reform.......................................35 Chapter 5 Local Democracy..............................................................................................40 -

Odderen I Århus Amt

ODDEREN I ÅRHUS AMT ÅRHUS AMT NATUR OG MILJØ JUNI 2003 Udgiver: Århus Amt Natur og Miljø Lyseng Allé 1 8270 Højbjerg Tlf. 89 44 66 66 Udgivelsesår: 2003 Titel: Odderen i Århus amt Redaktion: Lasse Werling, Jens Muff Hansen, Naturplan Registreringer: Feltregistrering for Århus Amt i 1998-99: Konsulent Jørgen Terp Laursen Layout: Gerda Skytte Illustr./fotos: © Århus Amt. Hvor andet er nævnt © den respektive tegner/fotograf Omslagsfoto af odder: Chr. A. Jensen Emneord: Odder, spredningskorridorer, spærringer, faunapassager ISBN: 87-7906-260-1 Oplag: 750 Sidetal: 28 Tryk: Århus Amts Trykkeri, trykt på miljøpapir T0-kort: © Udtegnet på grundlag af tekniske kortdata, Kortets informationer må ikke afdigitaliseres eller anvendes kommercielt Øvrige grundkort: © Kort- og Matrikelstyrelsen Rapporten kan ses på Natur og Miljøs hjemmeside www.aaa.dk/nm Henvendelse vedr. rapporten: Ring direkte til Natur og Miljø på tlf. 89 44 67 74 ODDEREN I ÅRHUS AMT INDHOLD ODDEREN ER PÅ VEJ FREM 3VI KAN LEVE MED ODDEREN ! 24 Dambrug 24 ET LIV I DET SKJULTE 4 Fiskeri og jagt 24 Udseende 4 Levevis 4 I ODDERENS FODSPOR 25 Unger hele året 5 Fortsat overvågning 25 Genetik 5 Alle kan hjælpe med at registrere oddere 25 Feltbestemmelse af odder og spor efter odder 26 HVORFOR BEVARE ODDEREN? 7 Indsendelse af oplysninger 26 Et tegn på god naturkvalitet 7 Bedre naturoplevelse 7 OPLYSNINGSSKEMA 27 National og international forpligtelse 7 PRAKTISKE OPLYSNINGER 28 DEN NATIONALE FORVALTNINGSPLAN Tilskud og støtte 28 FOR ODDER 8 Vedligeholdelse af vandløb 28 En fælles linie 8 Tilladelser -

ELENA Completed Project Factsheet Aarhus Light Rail

European Investment Bank Aarhus Light Rail ELENA Completed Project Factsheet Aarhus Light Rail Municipalities of Aarhus, Odder, Midtdjurs and Norddjurs in the eastern part of Location Central Denmark Region Beneficiary Aarhus Letbane I/S (Aarhus Light Rail I/S) CoM signatory Yes (Municipality of Aaarhus signed in January 2009) Sector Public Transport Total PDS costs EUR 2 508 554.70 ELENA contribution EUR 1 881 416.02 The overall aims were to Aarhus Light Rail I/S to improve quality and energy efficiency of the transport system: Support of studies to find the best energy efficient solutions for the power Project development supply of the system, covering both urban and suburban environments, where services the current supply systems were not the same financed by ELENA Support search of innovative technical solutions on how to transform a traditional local passenger and freight railway line into a light rail network with a freight transport capability Support to ensure the necessary permits and agreements with the stakeholders and organisations included in the project ELENA support has allowed the recruitment of both internal and external technical assistance. The coordinated approach for the integration of the existing railway Description lines into light rail operation was divided into two work packages: of ELENA operation WP1:Preparation for technical integration for freight and light rail WP2: Studies and integration of innovative solutions for energy efficiency and power supply Timeframe June 2013 – June 2016 The goal was that the innovative approach of forming a Light Rail Transit Corporation that benefit the future expansion of a light rail network in the eastern part of the Central Denmark Region. -

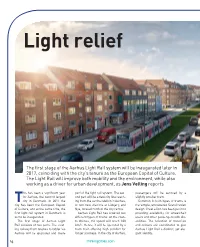

Light Relief

Light relief The first stage of the Aarhus Light Rail system will be inaugurated later in 2017, coinciding with the city’s tenure as the European Capital of Culture. The Light Rail will improve both mobility and the environment, while also working as a driver for urban development, as Jens Velling reports his has been a significant year part of the light rail system. The sec- passengers will be serviced by a for Aarhus, the second largest ond part will be a new city line reach- slightly smaller tram. Tcity in Denmark. In 2017 the ing from the central station in Aarhus, Common to both types of trams is city has been the European Capital to two new districts at LisbJerg and the simple, uncluttered Scandinavian of Culture, and at the same time, the Nye, located north of the city centre. design. Great effort has been put in to first light rail system in Denmark is Aarhus Light Rail has ordered two providing availability for wheelchair set to be inaugurated. different types of trains: on the route users and other passengers with dis- The first stage of Aarhus Light to Grenaa, the speed will reach 100 abilities. The selection of materials Rail consists of two parts. The exist- km/h. Hence, it will be operated by a and colours are coordinated to give ing railway from Grenaa to Odder via tram-train offering high comfort for Aarhus Light Rail a distinct, yet ele- Aarhus will be upgraded and made longer Journeys. In the city of Aarhus, gant identity. 14 thinkingcities.com Aarhus.indd 14 18/05/2017 15:15 AN ALTERNATIVE and cars. -

Fredede Bygninger

Fredede Bygninger September 2021 SLOTS- OG KULTURSTYRELSEN Fredninger i Assens Kommune Alléen 5. Løgismose. Hovedbygningen (nordøstre fløj beg. af 1500-tallet; nordvestre fløj 1575, ombygget 1631 og 1644; trappetårn og sydvestre fløj 1883). Fredet 1918.* Billeskovvej 9. Billeskov. Hovedbygningen (1796) med det i haven liggende voldsted (1577). Fredet 1932. Brahesborgvej 29. Toftlund. Det fritliggende stuehus (1852-55, ombygget sidst i 1800-tallet), den fritliggende bindingsværksbygning (1700-tallet), den brostensbelagte gårdsplads og kastaniealléen ved indkørslen. Fredet 1996.* Delvis ophævet 2016 Brydegaardsvej 10. Brydegård. Stuehuset, stenhuset (ca. 1800), portbygningen og de to udhusbygninger (ca. 1890) samt smedien (ca. 1850). F. 1992. Byvejen 11. Tjenergården. Det firelængede anlæg bestående af et fritliggende stuehus (1821), tre sammenbyggede stald- og ladebygninger og hesteomgangsbygningen på østlængen (1930) samt brolægningen på gårdspladsen. F. 1991.* Damgade 1. Damgade 1. De to bindingsværkshuse mod Ladegårdsgade (tidl. Ladegårdsgade 2 og 4). Fredet 1954.* Dreslettevej 5. Dreslettevej 5. Det firelængede gårdanlæg (1795, stuehuset forlænget 1847), tilbygningen på vestlængen (1910) og den brolagte gårdsplads. F. 1990. Ege Allé 5. Kobbelhuset. Det tidligere porthus. Fredet 1973.* Erholmvej 25. Erholm. Hovedbygningen og de to sammenbyggede fløje om gårdpladsen (1851-54 af J.D. Herholdt). Fredet 1964.* Fåborgvej 108. Fåborgvej 108. Det trelængede bygningsanlæg (1780-90) i bindingsværk og stråtag bestående af det tifags fritliggende stuehus og de to symmetrisk beliggende udlænger, begge i fem fag, den ene med udskud og den anden forbundet med stuehuset ved en bindingsværksmur forsynet med en revledør - tillige med den brostensbelagte gårdsplads indrammet af bebyggelsen. F. 1994. Helnæs Byvej 3. Bogården. Den firelængede gård (stuehuset 1787, udlængerne 1880'erne). -

Daily Life in Denmark in the 19Th Century

The Bridge Volume 37 Number 1 Article 7 2014 Daily Life in Denmark in the 19th Century Sofie Krogh Nielsen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/thebridge Part of the European History Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, and the Regional Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Nielsen, Sofie Krogh (2014) "Daily Life in Denmark in the 19th Century," The Bridge: Vol. 37 : No. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/thebridge/vol37/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Bridge by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Daily Life in Denmark in the 19th Century by Sofie Kr0gh Nielsen The 19th century entailed a lot of change in Denmark. For instance, industrialization broke through and changed the landscape, society, and conditions of life; the 1849 Constitution abolished absolute monarchy so that the political scene was changed. The 19th century was also the century where nationalism started to blossom and the idea of one nation with one people and one language developed. Moreover, Denmark was reduced from a great power to a small state with the loss of Norway in 1814 and the duchies of Slesvig, Holstein, and Lauenburg in 1864. Finally, it was also a century of emigration, especially to the U.S. All these changes affected daily life in Denmark in the 19th century. The aim of this article is to give an idea of the kind of life Danish immigrants left when they came to the U.S., by exploring themes such as urbanization, employment and basis for living, social services, food, political rights, women's rights, and the lives of children in 19th century Danish society. -

ELENA Fact Sheet Location Eastern Part of the Central Denmark Region (Østjylland). Four Municipalities

LETBANEN.DK ELENA Fact Sheet Location Eastern part of the Central Denmark Region (Østjylland). Four municipalities - Odder Municipality, Aarhus Municipality, Syddjurs Municipality and Norddjurs Municipality Beneficiary Aarhus Letbane I/S (Aarhus Light Rail I/S) CoM signatory The majority owner of Aarhus Light Rail I/S – The Municipality of Aarhus - signed the Covenant of Mayors on January 19th 2009. Sector Public Transport Total PDS cost EUR 2,549,000 Elena contribution EUR 1,911,750 (75%) Project development ELENA will support Aarhus Light Rail I/S with additional services (PDS) resources to improve both quality and energy efficiency of the financed by ELENA transport system: ELENA will support studies to find the best energy efficient solutions for the power supply of the system, covering both urban and suburban environments, where the power supply systems are different. ELENA will support the research of innovative technical solutions on how to transform a traditional local freight and passenger rail line into a light rail network with rail freight capability. ELENA will provide support to strengthen the current organisation. Due to the complexity of the project Aarhus Light Rail I/S has to hire more people - primarily specialist and lawyers - to ensure the necessary permits and agreements with the stakeholders and organisations involved in the project. Aligning the stakeholders is crucial to achieve a successful implementation of the project, which will be able to finish and operate on time. ELENA will bring additional support from external experts to fill the gap between internal expertise and standard solutions and the complexity and specificity of the activities to be carried out. -

Trafik-, Bygge- Og Boligstyrelsen Danish Transport, Construction and Housing Authority

Trafik-, Bygge- og Boligstyrelsen Danish Transport, Construction and Housing Authority Danish Implementation Plan for CCS TSI 2018 Memorandum Date 31 January 2019 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 DANSK IMPLEMENTERINGSPLAN FOR TSI CCS 2018 ...................................... 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................. 6 BACKGROUND .............................................................................................................. 7 0.1. Private railways ........................................................................................................ 9 0.2. Rail links to other EU Member States .................................................................... 9 0.3 Possible limitations .................................................................................................. 10 ANNEX ........................................................................................................................... 11 0. TARGET LINES: ................................................................................................... 11 0.1. THE DANISH RAIL NETWORK ............................................................................ 11 0.1.1. The Danish state rail network .......................................................................... 11 0.1.2. DSB’s rail infrastructure .................................................................................. 11 0.1.3. Private railways ................................................................................................