BIBLIOGRA~Li DAT SHE ""1).;-" Ib 3 J.):3-)- A/[12

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shelter Cluster Dashboard NWSW052021

Shelter Cluster NW/SW Cameroon Key Figures Individuals Partners Subdivisions Cameroon 03 23,143 assisted 05 Individual Reached Trend Nigeria Furu Awa Ako Misaje Fungom DONGA MANTUNG MENCHUM Nkambe Bum NORD-OUEST Menchum Nwa Valley Wum Ndu Fundong Noni 11% BOYO Nkum Bafut Njinikom Oku Kumbo Belo BUI Mbven of yearly Target Njikwa Akwaya Jakiri MEZAM Babessi Tubah Reached MOMO Mbeggwi Ngie Bamenda 2 Bamenda 3 Ndop Widikum Bamenda 1 Menka NGO KETUNJIA Bali Balikumbat MANYU Santa Batibo Wabane Eyumodjock Upper Bayang LEBIALEM Mamfé Alou OUEST Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Fontem Nguti KOUPÉ HNO/HRP 2021 (NW/SW Regions) Toko MANENGOUBA Bangem Mundemba SUD-OUEST NDIAN Konye Tombel 1,351,318 Isangele Dikome value Kumba 2 Ekondo Titi Kombo Kombo PEOPLE OF CONCERN Abedimo Etindi MEME Number of PoC Reached per Subdivision Idabato Kumba 1 Bamuso 1 - 100 Kumba 3 101 - 2,000 LITTORAL 2,001 - 13,000 785,091 Mbongé Muyuka PEOPLE IN NEED West Coast Buéa FAKO Tiko Limbé 2 Limbé 1 221,642 Limbé 3 [ Kilometers PEOPLE TARGETED 0 15 30 *Note : Sources: HNO 2021 PiN includes IDP, Returnees and Host Communi�es The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Key Achievement Indicators PoC Reached - AGD Breakdouwn 296 # of Households assisted with Children 27% 26% emergency shelter 1,480 Adults 21% 22% # of households assisted with core 3,769 Elderly 2% 2% relief items including prevention of COVID-19 21,618 female male 41 # of households assisted with cash for rental subsidies 41 Households Reached Individuals Reached Cartegories of beneficiaries reported People Reached by region Distribution of Shelter NFI kits integrated with COVID 19 KITS in Matoh town. -

Assessment of Prunus Africana Bark Exploitation Methods and Sustainable Exploitation in the South West, North-West and Adamaoua Regions of Cameroon

GCP/RAF/408/EC « MOBILISATION ET RENFORCEMENT DES CAPACITES DES PETITES ET MOYENNES ENTREPRISES IMPLIQUEES DANS LES FILIERES DES PRODUITS FORESTIERS NON LIGNEUX EN AFRIQUE CENTRALE » Assessment of Prunus africana bark exploitation methods and sustainable exploitation in the South west, North-West and Adamaoua regions of Cameroon CIFOR Philip Fonju Nkeng, Verina Ingram, Abdon Awono February 2010 Avec l‟appui financier de la Commission Européenne Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... i ABBREVIATIONS ...................................................................................................... ii Abstract .................................................................................................................. iii 1: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Problem statement ...................................................................................... 2 1.3 Research questions .......................................................................................... 2 1.4 Objectives ....................................................................................................... 3 1.5 Importance of the study ................................................................................... 3 2: Literature Review ................................................................................................. -

PC19 Inf. 12 (In English and French / En Inglés Y Francés / En Anglais Et Français)

PC19 Inf. 12 (In English and French / en inglés y francés / en anglais et français) CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA CONVENCIÓN SOBRE EL COMERCIO INTERNACIONAL DE ESPECIES AMENAZADAS DE FAUNA Y FLORA SILVESTRES CONVENTION SUR LE COMMERCE INTERNATIONAL DES ESPECES DE FAUNE ET DE FLORE SAUVAGES MENACEES D'EXTINCTION ____________ Nineteenth meeting of the Plants Committee – Geneva (Switzerland), 18-21 April 2011 Decimonovena reunión del Comité de Flora – Ginebra (Suiza), 18-21 de abril de 2011 Dix-neuvième session du Comité pour les plantes – Genève (Suisse), 18 – 21 avril 2011 PRELIMINARY REPORT ON SUSTAINABLE HARVESTING OF PRUNUS AFRICANA (ROSACEAE) IN THE NORTH WEST REGION OF CAMEROON The attached information document has been submitted by the CITES Secretariat1. El documento informativo adjunto ha sido presentado por la Secretaría CITES2. Le document d'information joint est soumis par le Secrétariat CITES3. 1 The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CITES Secretariat or the United Nations Environment Programme concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. 2 Las denominaciones geográficas empleadas en este documento no implican juicio alguno por parte de la Secretaría CITES o del Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Medio Ambiente sobre la condición jurídica de ninguno de los países, zonas o territorios citados, ni respecto de la delimitación de sus fronteras o límites. -

“These Killings Can Be Stopped” RIGHTS Government and Separatist Groups Abuses in Cameroon’S WATCH Anglophone Regions

HUMAN “These Killings Can Be Stopped” RIGHTS Government and Separatist Groups Abuses in Cameroon’s WATCH Anglophone Regions “These Killings Can Be Stopped” Abuses by Government and Separatist Groups in Cameroon’s Anglophone Regions Copyright © 2018 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-36352 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JULY 2018 ISBN: 978-1-6231-36352 “These Killings Can Be Stopped” Abuses by Government and Separatist Groups in Cameroon’s Anglophone Regions Map .................................................................................................................................... i Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations ............................................................................................................. -

SSA Infographic

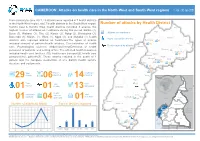

CAMEROON: Attacks on health care in the North-West and South-West regions 1 Jan - 30 Jun 2021 From January to June 2021, 29 attacks were reported in 7 health districts in the North-West region, and 7 health districts in the South West region. Number of attacks by Health District Kumbo East & Kumbo West health districts recorded 6 attacks, the Ako highest number of attacks on healthcare during this period. Batibo (4), Wum Buea (3), Wabane (3), Tiko (2), Konye (2), Ndop (2), Benakuma (2), Attacks on healthcare Bamenda (1), Mamfe (1), Wum (1), Nguti (1), and Muyuka (1) health Injury caused by attacks Nkambe districts also reported attacks on healthcare.The types of attacks Benakuma 01 included removal of patients/health workers, Criminalization of health 02 Nwa Death caused by attacks Ndu care, Psychological violence, Abduction/Arrest/Detention of health Akwaya personnel or patients, and setting of fire. The affected health resources Fundong Oku Kumbo West included health care facilities (10), health care transport(2), health care Bafut 06 Njikwa personnel(16), patients(7). These attacks resulted in the death of 1 Tubah Kumbo East Mbengwi patient and the complete destruction of one district health service Bamenda Ndop 01 Batibo Bali 02 structure and equipments. Mamfe 04 Santa 01 Eyumojock Wabane 03 Total Patient Healthcare 29 Attacks 06 impacted 14 impacted Fontem Nguti Total Total Total 01 Injured Deaths Kidnapping EXTRÊME-NORD Mundemba FAR-NORTH CHAD 01 01 13 Bangem Health Total Ambulance services Konye impacted Detention Kumba North Tombel NONORDRTH 01 04 destroyed 01 02 NIGERIA Bakassi Ekondo Titi Number of attacks by Month Type of facilities impacted AADAMAOUADAMAOUA NORTH- 14 13 NORD-OUESTWEST Kumba South CENTRAL 12 WOUESTEST AFRICAN Mbonge SOUTH- SUD-OUEST REPUBLIC 10 WEST Muyuka CCENTREENTRE 8 01 LLITITTORALTORAL EASESTT 6 5 4 4 Buea 4 03 Tiko 2 Limbe Atlantic SSUDOUTH 1 02 Ocean 2 EQ. -

Cameroon Humanitarian Situation Report

Cameroon Humanitarian Situation Report ©UNICEF Cameroon/2019 SITUATION IN NUMBERS Highlights August 2019 2,300,000 • More than 118,000 people have benefited from UNICEF’s # of children in need of humanitarian assistance humanitarian assistance in the North-West and South-West 4,300,000 regions since January including 15,800 in August. # of people in need (Cameroon Humanitarian Needs Overview 2019) • The Rapid Response Mechanism (RRM) strategy, Displacement established in the South-West region in June, was extended 530,000 into the North-West region in which 1,640 people received # of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) in the North- WASH kits and Long-Lasting Insecticidal Nets (LLINs) in West and South-West regions (OCHA Displacement Monitoring, July 2019) August. 372,854 # of IDPs and Returnees in the Far-North region • In August, 265,694 children in the Far-North region were (IOM Displacement Tracking Matrix 18, April 2019) vaccinated against poliomyelitis during the final round of 105,923 the vaccination campaign launched following the polio # of Nigerian Refugees in rural areas (UNHCR Fact Sheet, July 2019) outbreak in May. UNICEF Appeal 2019 • During the month of August, 3,087 children received US$ 39.3 million psychosocial support in the Far-North region. UNICEF’s Response with Partners Total funding Funds requirement received Sector Total UNICEF Total available 20% $ 4.5M Target Results* Target Results* Carry-over WASH: People provided with 374,758 33,152 75,000 20,181 $ 3.2 M access to appropriate sanitation 2019 funding Education: Number of boys and requirement: girls (3 to 17 years) affected by 363,300 2,415 217,980 0 $39.3 M crisis receiving learning materials Nutrition**: Number of children Funding gap aged 6-59 months with SAM 60,255 39,727 65,064 40,626 $ 31.6M admitted for treatment Child Protection: Children reached with psychosocial support 563,265 160,423 289,789 87,110 through child friendly/safe spaces C4D: Persons reached with key life- saving & behaviour change 385,000 431,034 messages *Total results are cumulative. -

CAMEROON Price Bulletin August 2021

CAMEROON Price Bulletin August 2021 The Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) monitors trends in staple food prices in countries vulnerable to food insecurity. For each FEWS NET country and region, the Price Bulletin provides a set of charts showing monthly prices in the current marketing year in selected urban centers and allowing users to compare current trends with both five-year average prices, indicative of seasonal trends, and prices in the previous year. Sorghum, maize, millet, and rice are the primary staples grown and consumed in the Far North region of Cameroon. Legumes such as cowpeas and groundnuts are also widely consumed. Onion is an important cash crop. Maroua and Kousseri host the most important reference markets in the Far North, responsible for the flow from rural to urban areas during harvest, and the opposite during the lean season. Other important reference markets include Mora, Mokolo, and Yagoua. Markets in the Far North play an important role in regional trade with neighboring Chad and Northeast Nigeria. However, as result of insecurity and conflict in the Greater Lake Chad basin, these trade corridors are often closed by the government, re-orientating trade flow more towards southern destinations, precisely Yaounde, Douala, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea and the Central Africa Republic (CAR). The Northwest region is a major production basin for maize and beans, while the Southwest region produces mainly plantain, cassava, and cocoyam. Potato and rice are also important crops Source: FEWS NET gratefully acknowledges DRADER, produced and consumed in both regions. Palm oil is produced in Cameroon for the market data and information used to both regions as an important cash crop sold mostly processed. -

Changements Institutionnels, Statégies D'approvisionnement Et De Gouvernance De L'eau Sur Les Hautes Terres De L'ou

Changements institutionnels, statégies d’approvisionnement et de gouvernance de l’eau sur les hautes terres de l’Ouest Cameroun : exemples des petites villes de Kumbo, Bafou et Bali Gillian Sanguv Ngefor To cite this version: Gillian Sanguv Ngefor. Changements institutionnels, statégies d’approvisionnement et de gouvernance de l’eau sur les hautes terres de l’Ouest Cameroun : exemples des petites villes de Kumbo, Bafou et Bali. Géographie. Université Toulouse le Mirail - Toulouse II, 2014. Français. NNT : 2014TOU20006. tel-01124258 HAL Id: tel-01124258 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01124258 Submitted on 6 Mar 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 5)µ4& &OWVFEFMPCUFOUJPOEV %0$503"5%&-6/*7&34*5²%&506-064& %ÏMJWSÏQBS Université Toulouse 2 Le Mirail (UT2 Le Mirail) $PUVUFMMFJOUFSOBUJPOBMFBWFD 1SÏTFOUÏFFUTPVUFOVFQBS NGEFOR Gillian SANGUV -F mercredi 29 janvier 2014 5Jtre : INSTITUTIONAL CHANGES, WATER ACCESSIBILITY STRATEGIES AND GOVERNANCE IN THE CAMEROON WESTERN HIGHLANDS: THE CASE OF BALI, KUMBO AND BAFOU SMALL CITIES. École doctorale -

Cameroon : Transport Sector Support Programme – Phase Iii – Construction of the Ring Road

GROUPE DE LA BANQUE AFRICAINE DE DÉVELOPPEMENT CAMEROON : TRANSPORT SECTOR SUPPORT PROGRAMME – PHASE III – CONSTRUCTION OF THE RING ROAD CODE SAP : P-CM-DB0-017 ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT PLAN (ESMP) SUMMARY May 2018 P. S. MORE NDONG, Principal Transport Team Leader COCM Engineer J. P. KALALA, Chief Socio-Economist PICU.0 A. KARANGA, Chief Transport Economist RDGC.4 N. M. T. DIALLO, Regional Financial COCM Management Coordinator C. N’KODIA, Principal Country Economist COCM Team Members G. BEZABEH, Road Safety Specialist PICU.1 Project Team C. L. DJEUFO, Procurement Officer COCM A. KAMGA, Disbursement Specialist COCM S. MBA, Consultant Transport Engineer COCM M.BAKIA, Chief Environmentalist RDGC.4 Director-General Ousmane DORE RDGC Sector Director Amadou OUMAROU PICU.0 Country Manager Solomane KONE COCM Sector Division Jean Kizito KABANGUKA PICU.1 Manager 1 1. INTRODUCTION The project objective is to asphalt a section of National Road No. 11 (RN11), namely the Bamenda- Ndop-Kumbo-Nkambe-Misaje-Mungong-Kimbi-Nyos-Weh-Wum-Bamenda“Ring Road” (approximately 357 km long) in Cameroon’s North-West Region. The project is classified under Category 1 in view of its potential impacts, and an Environmental and Social Impact Assessment is required by the Cameroon Government as well as the African Development Bank, which also makes the preparation of an Environmental and Social Management Plan (ESMP) and a Resettlement Action Plan (RAP) mandatory. This ESMP is a summary and a schedule of the implementation of the environmental and social measures recommended, the purpose of which is to provide sustainable responses to the impacts listed in the Project Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA). -

CAMEROON, FIRST QUARTER 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020

CAMEROON, FIRST QUARTER 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; in- cident data: ACLED, 20 June 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 CAMEROON, FIRST QUARTER 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Violence against civilians 162 92 263 Conflict incidents by category 2 Battles 111 50 316 Development of conflict incidents from March 2018 to March 2020 2 Strategic developments 39 0 0 Protests 23 1 1 Methodology 3 Riots 14 4 5 Conflict incidents per province 4 Explosions / Remote 10 7 22 violence Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 359 154 607 Disclaimer 5 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). Development of conflict incidents from March 2018 to March 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). 2 CAMEROON, FIRST QUARTER 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Methodology on what level of detail is reported. Thus, towns may represent the wider region in which an incident occured, or the provincial capital may be used if only the province The data used in this report was collected by the Armed Conflict Location & Event is known. -

CAMEROON: NORTH-WEST REGION Humanitarian Access Snapshot August 2021

CAMEROON: NORTH-WEST REGION Humanitarian access snapshot August 2021 Furu-Awa It became more challenging for humanitarian organisations in recent months to safely reach people in need in Cameroon’s North-West region. A rise in non-state armed groups (NSAGs) activities, ongoing military operations, increased criminality, the use of improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and the rainy Ako season have all made humanitarian access more difficult. As a result, food insecurity has increased as humanitarian actors were not able to provide food assistance. Health facilities are running out of drugs and medical supplies and aid workers are at increased risk of crossfire, kidnapping and violent attacks. Misaje Nkambe Fungom Fonfuka IED explosion Mbingo Baptist Hospital Nwa Road with regular Main cities Benakuma Ndu traffic Other Roads Akwaya Road in poor Wum condition and Country boundary Nkum Fundong NSAGs presence Oku but no lockdown Region boundaries Njinikom Kumbo Road affected by Division boundaries Belo NSAG lockdowns Subdivision boundaries Njikwa Bafut Jakiri Noni Mbengwi Mankon Bambui Andek Babessi Nkwen Bambili Ndop Bamenda Balikumbat Widikum Bali Santa N Batibo 0 40 Km The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. 1 Creation date: August 2021 Sources: Acces Working Group, OCHA, WFP. Feedback: [email protected] www.unocha.org https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/operations/cameroon/north-west-and-south-west-crisis CAMEROON: NORTH-WEST REGION Humanitarian access snapshot August 2021 • In August 2021, four out of the six roads out of Bamenda were affected by NSAG-imposed lockdowns, banning all vehicle • During the rainy season, the road from Bamenda to Bafut and traffic, including humanitarian operations. -

CPIN Template 2018

Country Policy and Information Note Cameroon: North-West/South-West crisis Version 2.0 December 2020 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the Introduction section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into two main sections: (1) analysis and assessment of COI and other evidence; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Assessment This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note – i.e. the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw – by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment of, in general, whether one or more of the following applies: • A person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm • The general humanitarian situation is so severe as to breach Article 15(b) of European Council Directive 2004/83/EC (the Qualification Directive)/Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iii) of the Immigration Rules • The security situation presents a real risk to a civilian’s life or person such that it would breach Article 15(c) of the Qualification Directive as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iv) of the Immigration Rules • A person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) • A person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory • A claim is likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and • If a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.