Memento Park,Budapest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Budapest Travel Guide

BUDAPEST TRAVEL GUIDE FIREFLIES TRAVEL GUIDES BUDAPEST Budapest is one of the world’s most beautiful cities. Both historical turbulence and a plethora of influences can be seen in the amazing mix of architecture, cuisine and culture. Close to the west, it is a realistic destination for short weekend breaks. It is also the ideal place for honeymoons or romantic getaways; the city is small enough to walk most of the sights and completely safe. Although Many tourist attraction have fees, there is a lot to be seen and absorbed just walking the streets, parks, markets and the peaceful Buda Hills. DESTINATION: BUDAPEST 1 BUDAPEST TRAVEL GUIDE Several pharmacies have 24-hour service numbers ESSENTIAL INFORMATION you can phone at any time, such as at Frankel Leo u. 22. +36 1 212 43 11 Mária Gyógyszertár 1139, Béke tér 11. +36 1 320 80 06 Royal Gyógyszertár 1073, Erzsébet krt. 58. +36 1 235 01 37 Uránia Gyógyszertár 1088, Rákóczi út 23. POST +36 1 338 4036 Post offices in Budapest are open Monday to Friday Széna-tér Patika-Fitotéka-Homeopátia from 8 am until 6 pm. 1015, Széna tér 1. +36 1 225 78 30 The post office at Nyugati railway station has additional opening hours: Mon to Sat 7 am until 9 www.google.hu/maps/search/budapest+gy%C3%B pm. 3gyszert%C3%A1r/@47.4969975,19.0554775,14z/ data=!3m1!4b1 Mammut posta Lövház utca 2-6. DENTIST 1024 +36 1 802 62 64 SOS Dental Service 1061 Király u. 14. József krt. 37-39 +36 1 322 96 02 1428 +36 1 318 26 66 Prime Dental Clinic 1027, Margit krt. -

Pocket Budapest 3 Preview

Contents Plan Your Trip 4 Welcome to Budapest ........4 Top Sights ............................6 Eating .................................10 Drinking & Nightlife ..........12 Shopping ............................14 Tours...................................16 Thermal Baths & Pools ....18 Entertainment .................. 20 Museum & Galleries .........21 For Kids ............................. 22 LGBT .................................. 23 Four Perfect Days ............24 Need to Know ................... 26 Matthias Church (p42), Castle District GTS PRODUCTIONS / SHUTTERSTOCK © 00--title-page-contents-pk-bud3.inddtitle-page-contents-pk-bud3.indd 2 77/03/2019/03/2019 22:24:37:24:37 PM Explore Survival Budapest 31 Guide 145 Castle District .................. 33 Before You Go ................ 146 Gellért Hill & Tabán ..........51 Arriving in Budapest ......147 Óbuda .................................67 Getting Around ...............147 Belváros ............................ 79 Essential Information .... 149 Parliament & Around ...... 89 Language .........................152 Margaret Island & Index .................................155 Northern Pest ................ 103 Erzsébetváros & the Jewish Quarter ..........111 Special Features Southern Pest ................ 129 Royal Palace .....................34 Gellért Baths .................... 52 Worth a Trip Citadella & Memento Park ..................64 Liberty Monument ...........54 Aquincum ...........................74 Parliament ........................90 Touring the Buda Hills ......76 Basilica -

Pocket Budapest 2 Preview

In This Book 16 Need to Know 17 18 Neighbourhoods 19 Arriving in Before You Go Getting Around Budapest Margaret Island & Need to Your Daily Budget Most people arrive in Budapest by air, but you Budapest has a safe, efficient and inexpen- Budapest Northern Pest can also get here from dozens of European sive public-transport system. Five types of (p84) Know Budget: Less than 15,000Ft cities by bus and train and from Vienna by transport are in general use, but the most Neighbourhoods This unspoiled island Parliament & Danube hydrofoil. relevant for travellers are the metro trains on in the Danube offers Around (p72) X Dorm bed: 3000–6500Ft QuickStart four numbered and colour-coded city lines, a green refuge, while Takes in the areas For more information, X Meal at self-service restaurant 1500Ft A From Ferenc Liszt International blue buses and yellow trams. The basic fare northern Pest beckons around the Parliament Óbuda (p50) with its shops and see Survival Guide (p145) X Three-day transport pass: 4150Ft Airport for all forms of transport is 350Ft (3000Ft building and the equally Minibuses, buses and trains to central for a block of 10) allowing you to travel as far This is the oldest part of lovely cafes. iconic Basilica of Currency Midrange: 15,000–35,000Ft Budapest run from 4am to midnight; taxis as you like on the same metro, bus, trolleybus Buda and retains a St Stephen, plus lost-in-the-past village Hungarian forint (Ft); some hotels quote X Single/double room: from 7500/10,000Ft cost from 6000Ft. -

Skansen Komunistycznej Rzeźby Pomnikowej W Budapeszcie

Muz.,2013(54): 224-231 Rocznik, ISSN 0464-1086 data przyjęcia – 02.2013 data akceptacji – 03.2013 SKANSEN KOMUNISTYCZNEJ RZEŹBY POMNIKOWEJ W BUDAPESZCIE Marcin Markowski Na południowo-zachodnich obrzeżach Budapesztu, w XXII szego losu pomników powstałych w czasach poprzedniego dzielnicy, znajduje się osobliwe muzeum minionej epoki – ustroju. Rozgorzały one wkrótce po obaleniu na Węgrzech Memento Park. Obiekt ten został wybudowany niedługo komunizmu. W tym czasie we wszystkich krajach komuni- po upadku komunizmu na Węgrzech. W miejscu tym, na stycznych Europy Wschodniej nastąpiły przemiany politycz- małej przestrzeni, zostały zebrane i wyeksponowane mo- ne. Wówczas z przestrzeni publicznej w państwach wschod- numentalne rzeźby. Powstałe w różnych okresach rządów nioeuropejskich, będących w orbicie wpływów ZSRR od komunistycznych na Węgrzech przez lata znajdowały się 1945 r., masowo usuwano nazwy ulic i placów oraz pomni- na placach oraz innych terenach publicznych węgierskiej ki gloryfi kujące komunistycznych bohaterów. Na Węgrzech stolicy. W tym muzeum na wolnym powietrzu można obej- została rozwiązana par a komunistyczna, zmieniono nazwę rzeć 42 monumenty, które zostały usunięte z przestrzeni państwa, godło i hymn3. Wśród pomysłów w kwes i tego, publicznej Budapesztu podczas transformacji ustrojowej co zrobić ze znajdującymi się w Budapeszcie pomnikami, w Europie Wschodniej w latach 1989–1990. Znajdujący się dominowały dwa stanowiska. Jedni chcieli ich demontażu w Budapeszcie park pomników ma za zadanie przybliżać oraz wymazania z pamięci i przestrzeni publicznej bohate- ikonografi ę komunistyczną pokoleniom, które nie miały rów okresu w historii Węgier pomiędzy 1945 a 1989 r. po- z nią styczności1. przez przetopienie upamiętniających ich pomników. Dru- Dnia 5 grudnia 1991 r. Rada Stolicy (Fővárosi Közgyűlés) dzy optowali za pozostawieniem ich na swoich miejscach przyjęła wniosek Komisji Kultury, który zalecał utworzenie i traktowaniem jako swego rodzaju reliktów poprzedniego w Budapeszcie parku rzeźb. -

Activities in Budapest Sights To

Activities in Budapest Sights to see 1) The Buda castle A must-see for everyone who visits the Hungarian capital. Besides its romantic streets, shops and cafés, the castle includes famous buildings such as the Matthias Church, the Fisherman’s bastion, or the National Gallery. Bus 16 takes you up to the castle, but you can also decide to walk from Clark Ádám Square – or take the unique funicular from there. 2) Gellért hill Gellért Hill is one of the top tourist attractions of the city thanks to the magnificent panorama from the top of its cliffs facing the Danube. You can climb the hill from two sides: take the stairs by the waterfall at Elizabeth Bridge, or take the gradual, but somewhat longer pathway by the Gellért Bath. 3) St. Stephan’s Basilica Located near to Deák Ferenc Square, St. Stephan’s Basilica is one of the most beautiful and monumental churches of Hungary. Here is found the ‘Holy Right’, a mummified right hand dedicated to St. Stephan, the first king of Hungary. 4) Heroes Square and Városliget Heroes Square with the statues of the most famous figures of Hungarian history is among the most popular sights of Budapest. Beyond the Square lies Városliget, the big city park of Budapest, which also includes the Vajdahunyad castle and the Széchényi thermal bath. To get there, take bus 105 or Metro line 1 (Földalatti) from Deák Ferenc tér. 5) Opera House The Hungarian State Opera is the masterpiece of Miklós Ybl, one of the greatest Hungarian architects of all time. The Opera was opened in 1884. -

Conference Guide

Conference Guide Conference Venue Conference Location: Continental Hotel Budapest The Continental Hotel Budapest The four star superior design hotel is located in Budapest's downtown offering 272 rooms - standard, executive, deluxe, suites- reflected by art deco features, perfect harmony and fine elegance combining a modern world of colours and forms. The hotel welcomes guests, providing business and tailor-made services with well-equipped conference rooms, Wellness and Fitness center, Massage, ARAZ Restaurant with terrace, Gallery Café & Corporate Lounge, underground private parking garage. Address: Dohány u. 42-44, Budapest H-1074, Hungary Tel: +36 1 815 1000 Fax: +36 1 815 1001 URL: http://www.continentalhotelbudapest.com/ History of Budapest Budapest is the capital and the largest city of Hungary, the largest in East-Central Europe and one of the largest cities in the European Union. The name "Budapest" is the composition of the city names "Buda" and "Pest", since they were united (together with Obuda) to become a single city in 1873. One of the first occurrences of the combined name "Buda-Pest" was in 1831 in the book "Vilag" ("World" / "Light"), written by Count Istvan Szechenyi. The origins of the words "Buda" and "Pest" are obscure. According to chronicles from the Middle Ages the name "Buda" comes from the name of its founder, Bleda (Buda), the brother of the Hunnic ruler Attila. The theory that "Buda" was named after a person is also supported by modern scholars. An alternative explanation suggests that "Buda" derives from the Slavic word "voda" ("water"), a translation of the Latin name "Aquincum", which was the main Roman settlement in the region. -

Museums of Communism in Eastern and Central Europe and Their Online Presence

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2013 Houses of History and Homepages: Museums of Communism in Eastern and Central Europe and their Online Presence Alexandra Day Coffman West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Coffman, Alexandra Day, "Houses of History and Homepages: Museums of Communism in Eastern and Central Europe and their Online Presence" (2013). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 514. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/514 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Houses of History and Homepages: Museums of Communism in Eastern and Central Europe and their Online Presence Alexandra Day Coffman A thesis submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Committee: Robert Blobaum, Ph.D. Katherine Aaslestad, Ph.D. Melissa Bingmann, Ph D. -

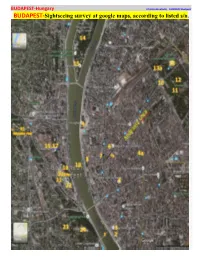

BUDAPEST-Sightseeing Survey at Google Maps, According to Listed S/N

BUDAPEST-Hungary Christos Gkoutzelis, HUNGARY-Budapest BUDAPEST-Sightseeing survey at google maps, according to listed s/n. 1. Liberty Bridge (Szabadsag hid) Liberty Bridge (Szabadság híd,is maybe the less attractive bridge in the city center ) is the one located at the southern end of city center, leading to Gellert Hill. The 333.6 m long bridge was built between 1894 and 1896. Its middle part was destroyed during World War II but it was rebuilt in 1945, and further restoration work was conducted to eliminate all war-related damage between 2007 and 2009. The bridge's main ornaments, four falcon-like bronze statues sitting on top of the bridge's four central masts (these are actually turuls, a mythological bird that represents power, strength and nobility in Hungary), were also restored. The bridge was originally named after the Emperor Franz Joseph, but it was renamed Liberty Bridge when the country was liberated from the Nazi occupation by the Soviet army at the end of World War II in 1945. The same year, the Liberation Monument was erected at the top of Gellert Hill. This imposing statue takes on the form of a woman holding a palm leaf above her head and can best be admired while crossing the bridge. 2. Corvinus University of Budapest (250m,3min from Szabadsag hid) In 1846, József Industrial School was opened gates for economics and trade for upper grade students. The immediate forerunner of the Corvinus University,the Faculty of Economics of the Royal Hungarian University, was established in 1920. The University admitting more than 14,000 students offers educational programmes inagricultural sciences, business administration, economics, and social sciences, and most these disciplines assure it a leading position in Hungarian higher education and is among the best institutions on various national and international rankings. -

Treasures of BUDAPEST

English Treasures of BUDAPEST TREASURES OF BUDAPEST CONTENTS SPICE OF EUROPE BUDAPEST – SPARKLING WITH LIFE 2 ARCHITECTURAL MASTERPIECES BE AMAZED BY BUDAPEST 4 HEALING WATERS, HEALTHY STAYS SPA CAPITAL OF THE WORLD 10 THE MODERN METROPOLIS FROM BAUHAUS TO BÁLNA BUDAPEST 14 CULTURE THROUGH THE CENTURIES CITY OF LISZT AND OPERA 16 FROM THE STONE AGE TO THE AVANT-GARDE GRAND MASTERS AND MODERN HISTORY 18 LOCAL HISTORY WRIT LARGE AND SMALL CUBES, QUEENS AND COLUMBO – URBAN ART IN BUDAPEST 20 PARK LIFE AND NATURE WALKS BUDAPEST’S GREAT GREEN OUTDOORS 22 SUMPTUOUS STAYS IN OPULENT SURROUNDINGS WHERE HISTORY MEETS LUXURY 26 DIVINE DOMESTIC DISHES HEAVENLY HUNGARIAN CUISINE FROM STARTERS TO DESSERT 30 BUDAPEST’S MARVELLOUS MARKETS SHOPPING FOR SUCCESS – WHERE STAR CHEFS SOURCE THEIR STOCK 32 IN VINO VERITAS SAVOUR FINE WINE IN BUDAPEST 34 WHERE HISTORY A ND COFFEE MIX A CENTURY OF COFFEEHOUSE CULTURE 36 DESIGNED BY HUNGARIANS, WORN BY CELEBS BUDAPEST, FASHION CAPITAL OF CENTRAL EUROPE 38 BUDAPEST AFTER DARK ROOFTOP COCKTAILS AND PARTY BOATS 44 CITY OF FEASTS AND FESTIVALS A FESTIVAL FOR EVERY OCCASION 42 MICE TOURISM ON THE RISE SCENIC SETTING FOR EVENTS, TRADE SHOWS AND CONFERENCES 44 FROM THE FIRST OLYMPICS TO FINA 2027 BUDAPEST TO STAGE MAJOR SPORTS FINALS 46 KEY DESTINATIONS AROUND THE CAPITAL FASCINATING DAY TRIPS FROM BUDAPEST 48 HIDDEN RETREATS NEAR BUDAPEST OFF THE BEATEN TRACK 52 GREAT GIFTS A ND PERFECT PRESENTS AUTHENTIC HUNGARIAN SOUVENIRS 56 HOW TO GET IN AND AROUND BUDAPEST BUDAPEST TRANSPORT TIPS 58 SPICE OF EUROPE Budapest basks in a wonderful built and natural environment, reflected in its UNESCO World Heritage sites such as the Banks BUDAPEST – SPARKLING of the Danube, the Buda Castle Quarter and Andrássy Avenue. -

The Places of Memory in a Square of Monuments: Conceptions of Past, Freedom and History at Szabadság Tér

Page 1 of 34 Erik Thorstensen. “The Places of Memory in a Square of Monuments: Conceptions of Past, Freedom and History at Szabadság Tér. AHEA: E-journal of the American Hungarian Educators Association, Volume 5 (2012): http://ahea.net/e-journal/volume-5- 2012 The Places of Memory in a Square of Monuments: Conceptions of Past, Freedom and History at Szabadság Tér Erik Thorstensen, The Center for Studies of Holocaust and Religious Minorities, Norway Abstract: In this paper I try to approach contemporary Hungarian political culture through an analysis of the history of changing monuments at Szabadság Tér in Budapest. The paper has as its point of origin a protest/irredentist monument facing the present Soviet liberation monument. In order to understand this irredentist monument, I look into the meaning of the earlier irredentist monuments under Horthy and try to see what monuments were torn down under Communism and which ones remained. I further argue that changes in the other monuments also affect the meaning of the others. From this background I enter into a brief interpretation of changes in memory culture in relation to changes in political culture. The conclusions point toward the fact that Hungary is actively pursuing a cleansing of its past in public spaces, and that this process is reflected in an increased acceptance of political authoritarianism. Keywords: monuments, Budapest, irredentism, memory, public spaces Biography: Erik Thorstensen has been an educator at the Center for Studies of Holocaust and Religious Minorities, Norway, since 2005. Previously he did research in ethics and lectured in history of religions at the University of Oslo. -

The Cultural and Collective Memory of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-19-2017 The Cultural and Collective Memory of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 Ted P. Tindell University of New Orleans, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Tindell, Ted P., "The Cultural and Collective Memory of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956" (2017). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 2360. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/2360 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Cultural and Collective Memory of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 A Thesis Submitted to the Department of History University of New Orleans In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In History By Ted P. Tindell BS, Tulane University, 1970 May 2017 Acknowledgements “To get the full value of joy you must have someone to divide it with.” ― Mark Twain The joy I have received on this journey to become more knowable about history has made every cent, minute of time, and struggle for comprehension an inconsequential price to pay. -

Between Monuments and Ruins, the Case of Contemporary Budapest Rodrigo Rieiro Díaz

109 Review Article The Memory Works: Between Monuments and Ruins, the Case of Contemporary Budapest Rodrigo Rieiro Díaz Introduction believed that in the metropolitan consumer’s ‘Memento Park Budapest. The gigantic memories discontinuous experience of reality there was an of communist dictatorship.’1 Thus reads the head emancipatory potential to break with the politically of the website of this theme park about honfibú, subjugating fantasy of progress. Therefore section next to pictures of the statues of the communist era five discusses Budapest’s success as the locus of that until recently embodied part of the Hungarian the redemption of the oppressed. Finally, in the last self-mythology.2 All these statues, now stored in a two sections the focus is directed towards the local park on the outskirts of Budapest, form a sort of phenomenon of romkocsma. It is employed as a contemporary Parco dei Mostri dedicated to tourism case of study to wonder whether urban phenomena and memory.3 Lying on vacant lots among electric of re-use of ruins could house an emancipatory poles, shrubs, and some small outbuildings, are potential or, conversely, serve the interests of the the statues of the mythical characters of the past, hegemonic groups and the contemporary dominant scattered like fallen gods. Precisely the same price, discourse. the loss of divinity and its transformation into the demonic, was the price that Walter Benjamin said City of memorials the pagan deities had to pay to survive the Christian Memento Park encloses the rejection of a rejected era, their only conceivable salvation. Benjamin’s past.