Framing Premodern Desires Framing Premodern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Magistrate and the Community: Summary Proceedings in Rural England During the Long Eighteenth Century Creator: Darby, N

This work has been submitted to NECTAR, the Northampton Electronic Collection of Theses and Research. Thesis Title: The magistrate and the community: summary proceedings in rural England during the long eighteenth century Creator: Darby, N. E. C. R Example citation: Darby, N. E. C. (2015) The magistrate and the community: summary proceedings in rural England during the long eiAghteenth century. Doctoral thesis. The University of Northampton. Version: Accepted version T http://nectarC.northampton.ac.uk/9720/ NE The magistrate and the community: summary proceedings in rural England during the long eighteenth century Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy At the University of Northampton 2015 Nerys Elizabeth Charlotte Darby © Nell Darby 2015. This thesis is copyright material and no quotation from it may be published without proper acknowledgement Abstract The study of how the law worked at a local level in rural communities, and in the role of the rural magistrate at summary level, has been the subject of relatively little attention by historians. More attention has been given to the higher courts, when the majority of plebeian men and women who experienced the law during the long eighteenth century would have done so at summary level. Although some work has been carried out on summary proceedings, this has also tended to focus either on metropolitan records, a small number of sources, or on a specific, limited, number of offences. There has not been a broader study of rural summary proceedings to look at how the role and function of the rural magistrate, how local communities used this level of the criminal justice system, as complainants, defendants and witnesses, and how they negotiated their place in their local community through their involvement with the local magistrate. -

Tamara Matheson

Chaplin Page 1 of 9 TAMARA CHAPLIN Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 309 Gregory Hall MC 466 810 South Wright Street Urbana, Illinois 61801 USA US Cell: 001 217 979 3990 / Email: [email protected] EMPLOYMENT 2008-present: Associate Professor of Modern European History, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC) Affilitated Faculty, Gender and Women’s Studies, UIUC Affiliated Faculty, Department of French and Italian, UIUC Associated Faculty, Unit for Criticism and Interpretive Theory Associated Faculty, European Union Center, UIUC Associated Faculty, Holocaust, Genocide and Memory Studies, UIUC 2002-2008: Assistant Professor of Modern European History, UIUC EDUCATION Ph.D. Modern European History, September 2002, Rutgers: The State University of NJ, New Brunswick, NJ, USA (1995-2002). Dissertation: “Embodying the Mind: French Philosophers on Television, 1951-1999” Advisors: Bonnie G. Smith (Director), Joan W. Scott, John Gillis, Herrick Chapman (NYU) Major Field: Modern Europe Minor Fields: Contemporary France/ Media History of Gender and Sexuality Cultural and Intellectual B.A. History, Honors with Great Distinction, September 1995, Concordia University, Montreal, Canada (1991-1995). FELLOWSHIPS AND AWARDS 2016 Summer NEH Summer Stipend ($6000 for June-July, 2016; book project on Desiring Women). 2016 Spring Camargo Foundation Fellowship, Cassis, France (housing, $1600 stipend, airfare). 2016 Spring Humanities Released Time, UIUC Research Board, Urbana, IL. 2015 Fall Zwickler Memorial Research Grant ($1350), Cornell University, NY. 2014 Summer Visiting Fellow, York University, York, England. 2014 Summer Provost’s Faculty Retreat Grant, UIUC, Urbana, IL http://wwihist258.weebly.com/ 2014 Spring UIUC Research Board Support: Research Assistant, UIUC, Urbana, IL. -

Courtesans in Colonial India Representations of British Power Through Understandings of Nautch-Girls, Devadasis, Tawa’Ifs, and Sex-Work, C

Courtesans in Colonial India Representations of British Power through Understandings of Nautch-Girls, Devadasis, Tawa’ifs, and Sex-Work, c. 1750-1883 by Grace E. S. Howard A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Grace E. S. Howard, May, 2019 ABSTRACT COURTESANS IN COLONIAL INDIA REPRESENTATIONS OF BRITISH POWER THROUGH UNDERSTANDINGS OF NAUTCH-GIRLS, DEVADASIS, TAWA’IF, AND SEX-WORK, C. 1750-1883 Grace E. S. Howard Advisors: University of Guelph Dr. Jesse Palsetia Dr. Norman Smith Dr. Kevin James British representations of courtesans, or nautch-girls, is an emerging area of study in relation to the impact of British imperialism on constructions of Indian womanhood. The nautch was a form of dance and entertainment, performed by courtesans, that originated in early Indian civilizations and was connected to various Hindu temples. Nautch performances and courtesans were a feature of early British experiences of India and, therefore, influenced British gendered representations of Indian women. My research explores the shifts in British perceptions of Indian women, and the impact this had on imperial discourses, from the mid-eighteenth through the late nineteenth centuries. Over the course of the colonial period examined in this research, the British increasingly imported their own social values and beliefs into India. British constructions of gender, ethnicity, and class in India altered ideas and ideals concerning appropriate behaviour, sexuality, sexual availability, and sex-specific gender roles in the subcontinent. This thesis explores the production of British lifestyles and imperial culture in India and the ways in which this influenced their representation of courtesans. -

63199 Exeter Register 2005

EXETER COLLEGE ASSOCIATION Register 2005 Contents From the Rector 3 From the President of the MCR 6 From the President of the JCR 10 Harry Radford by Jim Hiddleston 14 Exeter College Chapel 2004-2005 by Mark Birch. 15 Nearly a Hundred Years Ago: Seen in the Eastern Twilight 18 Exeter College in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography by John Maddicott 20 Undergraduate Life in the 1930s, with contributions by Leslie Le Quesne, Walter Luttrell, Eric Kemp and Hugh Eccles 28 Early Days by Michael Dryland 37 A Freshman Forty Years Ago by Graham Chainey 39 The Tutor’s Art, with contributions by Ben Morrison, John Brown, Michael Hart and Faramerz Dabhoiwala 45 College Notes and Queries 52 Corresponding Internationally by Martin Sieff 55 West Mercia Blues: Policing Highs and Lows by Sarah Fuller 58 On the Trail of Gilbert Scott: from Exeter to the East End by Andrew Wilson 60 The Governing Body 64 Honours and Appointments 65 Publications 66 Class Lists in Honour Schools 2005 68 Graduate Degrees 71 College and University Prizes 72 Graduate Freshers 73 Undergraduate Freshers 74 Deaths 78 Marriages 80 Births 80 Notices 81 1 Contributors Mark Birch is the College Chaplain. He was formerly a practising vet. Graham Chainey read English and is the author of A Literary History of Cambridge (Cambridge University Press, 1995). Michael Dryland was a Choral Exhibitioner and read English and then Jurisprudence after leaving the Navy. He was formerly Master of the Company of Merchant Taylors of York and senior partner in a York law practice. Hugh Eccles read Engineering. -

Exeter Register Cover 2007

EXETER COLLEGE ASSOCIATION Register 2007 Contents From the Rector 6 From the President of the MCR 10 From the President of the JCR 12 Alan Raitt by David Pattison 16 William Drower 18 Arthur Peacocke by John Polkinghorne 20 Hugh Kawharu by Amokura Kawharu 23 Peter Crill by Godfray Le Quesne 26 Rodney Hunter by Peter Stone 28 David Phillips by Jan Weryho 30 Phillip Whitehead by David Butler 34 Ned Sherrin by Tony Moreton 35 John Maddicott by Paul Slack and Faramerz Dabhoiwala 37 Gillian Griffiths by Richard Vaughan-Jones 40 Exeter College Chapel by Helen Orchard 42 Sermon to Celebrate the Restoration of the Chapel by Helen Orchard 45 There are Mice Throughout the Library by Helen Spencer 47 The Development Office 2006-7 by Katrina Hancock 50 The Association and the Register by Christopher Kirwan 51 A Brief History of the Exeter College Development Board by Mark Houghton-Berry 59 Roughly a Hundred Years Ago: A Law Tutor 61 Aubrey on Richard Napier (and his Nephew) 63 Quantum Computing by Andrew M. Steane 64 Javier Marías by Gareth Wood 68 You Have to Be Lucky by Rip Bulkeley 72 Memorabilia by B.L.D. Phillips 75 Nevill Coghill, a TV programme, and the Foggy Foggy Dew by Tony Moreton 77 The World’s First Opera by David Marler 80 A Brief Encounter by Keith Ferris 85 College Notes and Queries 86 The Governing Body 89 Honours and Appointments 90 Publications 91 Class Lists in Honour Schools and Honour Moderations 2007 94 Distinctions in Moderations and Prelims 2007 96 1 Graduate Degrees 2007 97 College Prizes 99 University Prizes 100 Graduate Freshers 2007 101 Undergraduate Freshers 2007 102 Deaths 105 Marriages 107 Births 108 Notices 109 2 Editor Christopher Kirwan was Fellow and Lecturer in Philosophy from 1960 to 2000. -

Reading Revolutionary Texts. Ed. Rachel Hammersley. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015

"Notes." Revolutionary Moments: Reading Revolutionary Texts. Ed. Rachel Hammersley. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015. 183–202. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 30 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474252669.0029>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 30 September 2021, 19:29 UTC. Copyright © Rachel Hammersley 2015. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. Notes I n t r o d u c t i o n 1 T. Skocpol, States and Social Revolutions: A Comparative Analysis of France, Russia, and China (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979). 2 Ibid , pp. 5 – 6. 3 See, for example, David Parker, Revolutions and the Revolutionary Tradition in the West, 1560-1991 (London and New York: Routledge, 2000); and Michael D. Richards, Revolutions in World History (London and New York: Routledge, 2004). 4 It has recently been suggested that Zhou Enlai actually misunderstood the question. See the blogpost by Dean Nicholas, dated 15 June 2011, on the History Today blog. Chapter 1 1 An Agreement of the People for a Firme and Present Peace (3 November 1647; British Library Th omason Tracts E412/21), pp. 2 – 4. Further references to this work will appear in parentheses in the text. 2 E. Vernon and P. Baker, ‘ Introduction: the History and Historiography of the Agreements of the People ’ , in Th e Agreements of the People, the Levellers and the Constitutional Crisis of the English Revolution , ed. P. Baker and E. Vernon (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), pp. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Randolph Trumbach ADDRESS

1 CURRICULUM VITAE Randolph Trumbach ADDRESS: Department of History Baruch College City University of New York One Bernard Baruch Way New York, NY 10010 (646) 312-4314 (Voice Mail); (646) 312-4310 (Secretary) E-mail: [email protected] Fax: (646) 312-4311 EDUCATION: Ph.D. The Johns Hopkins University 1972 M.A. Johns Hopkins 1966 B.A. University of New Orleans 1964 FELLOWSHIPS, GRANTS AND AWARDS: CUNY Graduate Center, Center for the Humanities, Mellon Fellowship, Mellon Foundation, (2009-10) Fellowship Leave, Baruch College, City University of New York, Spring 1988, February 2008-January 2009, September 2015- August 2016 Baruch College Presidential Excellence Awards for Distinguished Scholarship, 1979, 1999 Columbia University Seminars, Schoff Trust Fund Publications Award, 1993 City University of New York, Faculty Research Awards, 1973-75, 1977-78, 1978-79, 1979-80, 1985-86 Baruch College, Scholar Assistance Program, 1984, 1985 National Endowment for the Humanities, Summer Stipend, 1979 Newberry Library Grant-in-Aid, 1972 University of Chicago, Internship in Western Civilization, 1969-71 Johns Hopkins University Fellowships, 1964-69 Woodrow Wilson Fellowships, 1964-65, 1967-68 TEACHING APPOINTMENTS: Baruch College and the Graduate School City University of New York Professor of History, 1985 Baruch, 1995 Graduate School Associate Professor of History, 1979-1984 Assistant Professor of History, 1973-1978 (Tenured, September 1978) 2 University of Amsterdam, Visiting Professor, Summer, 1993 Columbia University, Adjunct Professor, Summer, 1991 University of Chicago, Intern, 1969-1971 Johns Hopkins University, Junior Instructor, 1966-1967 University of New Orleans, Lecturer, Summer, 1966 PRINCIPAL PUBLICATIONS: 1. BOOKS (1) The Rise of the Egalitarian Family: Aristocratic Kinship (2) and Domestic Relations in Eighteenth-Century England (New York and London: Academic Press, 1978). -

Sexuality: an Australian Historian's Perspective

Sexuality: An Australian Historian’s Perspective Frank Bongiorno Suppression N 2004 A CONTROVERSY ERUPTED WHEN IT CAME TO LIGHT THAT THE AUSTRALIAN education minister, Brendan Nelson, had vetoed several projects Irecommended for funding by the Australian Research Council (ARC). The provocation for Nelson’s action on behalf of the conservative government to which he belonged was an article published in a tabloid newspaper by right-wing columnist Andrew Bolt, criticising the ARC for supporting ‘peek-in-your-pants researchers fixated on gender or race’ (Bolt, ‘Grants to Grumble’). Bolt’s campaign against the ARC continued for several years, as did Nelson’s vetting of research proposals. Among the columnist’s targets were a project on ‘the cultural history of the body in modern Japan’, and another on ‘attitudes towards sexuality in Judaism and Christianity in the Hellenistic Greco-Roman era’ (Bolt, ‘Paid to be Pointless’; Macintyre). The identity of the researchers and projects that Nelson had actually rejected remained a secret but university researchers, guided by Bolt’s fixation with projects about sex, took for granted that these were prominent among those culled. One researcher later commented that applicants were omitting the words ‘sexuality’, ‘class’ and ‘race’ from proposals in an effort to avoid the minister’s wrath (Alexander). The episode raised many questions—including about academic freedom—but was of particular interest to researchers of sexuality. Why did such projects lend Bongiorno, Frank. ‘Sexuality: An Australian Historian’s -

FP 12.4 Winter1993.Pdf (4.166Mb)

WOMEN'S STUDIES LIBRARIAN The University of Wisconsin System EMINIST ERIODICALS A CURRENT LISTING OF CONTENTS VOLUME 12, NUMBER 4 WINTER 1993 Published by Phyllis Holman Weisbard Women's Studies Librarian University of Wisconsin System 430 Memorial Library / 728 State Street Madison, Wisconsin 53706 (608) 263-5754 EMINIST ERIODICALS A CURRENT LISTING OF CONTENTS Volume 12, Number 4 Winter 1993 Periodical literature is the cutting edge of women's scholarship, feminist theory, and much of women's culture. Feminist Periodicals: A Current Listing of Contents is published by the Office of the University of Wisconsin System Women's Studies Librarian on a quarterly basis with the intent of increasing public awareness of feminist periodicals. It is our hope that Feminist Periodicals will serve several purposes: to keep the reader abreast of current topics in feminist literature; to increase readers' familiarity with a wide spectrum of feminist periodicals; and to provide the requisite bibliographic information should a reader wish to subscribe to a journal or to obtain a particular article at her library or through interlibrary loan. (Users will need to be aware of the limitations of the new copyright law with regard to photocopying of copyrighted materials.) Table of contents pages from current issues of majorfeminist journals are reproduced in each issue of Feminist Periodicals, preceded by a comprehensive annotated listing of all journals we have selected. As publication schedules vary enormously, not every periodical will have table of contents pages reproduced in each issue of FP. The annotated listing provides the following information on each journal: 1. Year of first publication. -

Experiences of Illegitimacy in England, 1660-1834

Experiences of Illegitimacy in England, 1660-1834 Kate Louise Gibson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of History March 2018 Thesis Summary This thesis examines attitudes towards individuals who were born illegitimate in England between the Restoration in 1660 and the New Poor Law of 1834. It explores the impact of illegitimacy on individuals' experiences of family and social life, marriage and occupational opportunities, and sense of identity. This thesis demonstrates that illegitimacy did have a negative impact, but that this was not absolute. The stigma of illegitimacy operated along a spectrum, varying according to the type of parental relationship, the child's gender and, most importantly, the family's socio-economic status. Socio-economic status became more significant as an arbiter of attitudes towards the end of the period. This project uses a range of qualitative evidence - correspondence, life-writing, poor law records, novels, legal and religious tracts, and newspapers - to examine the impact of illegitimacy across the entire life-cycle, moving away from previous historiographical emphasis on unmarried parenthood, birth and infancy. This approach adds nuance to a field dominated by poor law and Foundling Hospital evidence, and prioritises material written by illegitimate individuals themselves. This thesis also has resonance for historical understanding of wider aspects of long- eighteenth-century society, such as the nature of parenthood, family, gender, or emotion, and the operation of systems of classification and 'othering'. This thesis demonstrates that definitions of parenthood and family were flexible enough to include illegitimate relationships. -

South Sudan: a Slow Liberation. by Edward Thomas. (London, United Kingdom: Zed Books, 2015. Pp. 321. $27.95.)

bs_bs_bannerbs_bs_bannerbs_bs_bannerbs_bs_bannerbs_bs_bannerbs_bs_banner © 2018 Phi Alpha Theta BOOK REVIEWS EDITORIAL OFFICE: Elliott Hall IV, Ohio Wesleyan University; Delaware, OH 43015. Telephone: 740-368-3642. Facsimile: 740-368-3643 E-MAIL ADDRESS: [email protected] WEB ADDRESS: http://go.owu.edu/~brhistor EDITOR Richard Spall Ohio Wesleyan University SENIOR EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS Alyssa DiPadova Kelsey Heath Henry Sloan Kyle Rabung EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS Amanda Hays Maddie Lancaster Jason Perry Haley Mees Slater Sabo Christopher Shanley WORD PROCESSING: Laurie George © 2018 Phi Alpha Theta AFRICA AND THE MIDDLE EAST Maimonides and the Merchants: Jewish Law and Society in the Medieval Islamic World. By Mark Cohen. (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017. Pp. 236. $65.00.) Among the many fine contributions of Maimonidean scholarship, this new monograph stands out for its fresh approach and promises to make a lasting impact on the field. In keeping with a growing scholarly trend, Mark Cohen’s book situates Maimonides’s work within the context of Egyptian and Mediterra- nean societies. But unlike those studies that examine Maimonides’s writings within the framework of Arab thought or Islamic law, Maimonides and the Merchants focusesontheintersectionoflawandrealityintheMishneh Torah, arguing that Maimonides subtly yet substantively updated the Jewish legal apparatus in order to accommodate economic norms current among medieval Mediterranean traders, Jewish and non-Jewish alike. Cohen draws from a wealth of Genizah documents, Gaonic responsa, and Islamic legal texts to illustrate the nature of the mercantile system that prevailed from at least the tenth century, known in some Gaonic sources as the “custom of the merchants” (hukm al-tujjâr). A key element of this system, generally known in Arabic as qirâd, was defined by its partnership structure, according to which a “passive” partner supplied the primary capital for the joint venture while an “active” partner supplied the labor in the form of travel and trade. -

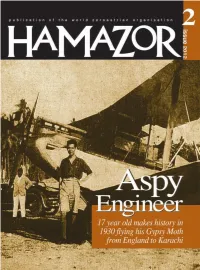

Aspy Meherwan Engineer

HAMAZOR - ISSUE 2 2012 Artist & Social Worker, Jimmy Engineer with Mother Teresa - p34 C o n t e n t s 04 Message from the Chairman, WZO 05 WZO celebrates Nowruz - sammy bhiwandiwalla 06 WZO Trust - An overview for 2011 - dinshaw tamboly 09 Zoroastrianism’s Influence on Christanity - keki bhote 11 Chawk blessings - shiraz engineer 12 The Avesta & its language at Oxford University from 1886 to present - elizabeth tucker COVER 15 The School of Religion at Claremont - arman ariane 16 An After-world itinerary - farrokh vajifdar Photograph of Aspy 21 Prayer & Worship - dina mcintyre Engineer when he landed in Karachi from 25 Legacy of Ancient Iran - philip kreyenbroek London in his Gypsy 28 “My little book of Zoroastrian prayer” - review magdalena rustomji Moth - an achievement 29 “Discovering Ashavan” - review debbie starzynski that made history. 30 Making a difference - marjorie husain Courtesy Cyrus Aspy Engineer 37 The Eighth Outrage - yesmin madon PHOTOGRAPHS 39 In the recall of times lost - jamsheed marker 44 Dilemmas around Development - homi khushrokhan Courtesy of individuals 47 Aspy Meherwan Engineer - rusi sorabji whose articles appear in the magazine or as 54 The Origins of sexual freedom in the West - soonu engineer mentioned 59 Reliable sites on Zoroastrianism on the Internet 60 Feeding the homeless one meal swipe at a time - rustom birdie 63 Nowrojee & Sons General Store www.w-z-o.org 1 In loving memory of my son Cyrus Happy Minwalla M e m b e r s o f t h e M a n a g i n g C o m m i t t e e London, England The World Zoroastrian