63199 Exeter Register 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Empty Tomb

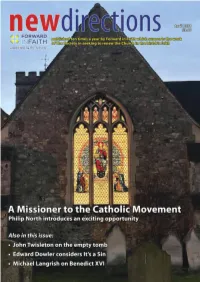

content regulars Vol 24 No 299 April 2021 6 gHOSTLy cOunSEL 3 LEAD STORy 20 views, reviews & previews AnDy HAWES A Missioner to the catholic on the importance of the church Movement BOOkS: Christopher Smith on Philip North introduces this Wagner 14 LOST SuffOLk cHuRcHES Jack Allen on Disability in important role Medieval Christianity EDITORIAL 18 Benji Tyler on Being Yourself BISHOPS Of THE SOcIETy 35 4 We need to talk about Andy Hawes on Chroni - safeguarding cles from a Monastery A P RIEST 17 APRIL DIARy raises some important issues 27 In it from the start urifer emerges 5 The Empty Tomb ALAn THuRLOW in March’s New Directions 19 THE WAy WE LIvE nOW JOHn TWISLETOn cHRISTOPHER SMITH considers the Resurrection 29 An earthly story reflects on story and faith 7 The Journal of Record DEnIS DESERT explores the parable 25 BOOk Of THE MOnTH WILLIAM DAvAgE MIcHAEL LAngRISH writes for New Directions 29 Psachal Joy, Reveal Today on Benedict XVI An Easter Hymn 8 It’s a Sin 33 fAITH Of OuR fATHERS EDWARD DOWLER 30 Poor fred…Really? ARTHuR MIDDLETOn reviews the important series Ann gEORgE on Dogma, Devotion and Life travels with her brother 9 from the Archives 34 TOucHIng PLAcE We look back over 300 editions of 31 England’s Saint Holy Trinity, Bosbury Herefordshire New Directions JOHn gAyfORD 12 Learning to Ride Bicycles at champions Edward the Confessor Pusey House 35 The fulham Holy Week JAck nIcHOLSOn festival writes from Oxford 20 Still no exhibitions OWEn HIggS looks at mission E R The East End of St Mary's E G V Willesden (Photo by Fr A O Christopher Phillips SSC) M I C Easter Chicks knitted by the outreach team at Articles are published in New Directions because they are thought likely to be of interest to St Saviour's Eastbourne, they will be distributed to readers. -

Day 3 IICSA Inquiry Anglican Church Investigation Hearing 25 July 2018

Day 3 IICSA Inquiry Anglican Church Investigation Hearing 25 July 2018 1 Wednesday, 25 July 2018 1 A. Yes. 2 (10.00 am) 2 Q. In your witness statement at paragraph 1 you describe 3 Welcome and opening remarks by THE CHAIR 3 the role as Secretary for Public Affairs as being 4 THE CHAIR: Good morning, everyone, and welcome to Day 3 of 4 essentially the archbishop's most senior adviser on 5 the Peter Ball case study. Today the inquiry will hear 5 things outside of the church? 6 witness evidence from Dr Purkis, from a former police 6 A. Correct. 7 officer and a serving police officer and the Reverend 7 Q. Am I right, broadly speaking, that the Bishop at 8 Dr Ros Hunt. 8 Lambeth, so at that point Bishop John Yates, was the 9 If there are no matters to deal with, Ms Bicarregui, 9 most senior person advising on matters to do with the 10 prior to hearing the witnesses? 10 church, so to do with ecclesiastical matters? 11 MS BICARREGUI: Thank you very much, chair. 11 A. Yes. 12 THE CHAIR: Please proceed. 12 Q. I believe you also worked very closely with 13 MS BICARREGUI: Dr Purkis's statement is in file 6. 13 Lesley Perry, who was the archbishop's press secretary 14 DR ANDREW PURKIS (sworn) 14 at that time? 15 Examination by MS BICARREGUI 15 A. Yes. 16 MS BICARREGUI: Dr Purkis, you should have a bundle of 16 Q. I think, if you look at your witness statement, or you 17 documents in front of you, and behind the first 17 may not need to, at paragraph 15.1, you say that a large 18 tab there should be a copy of your witness statement. -

Framing Premodern Desires Framing Premodern

9 CROSSING BOUNDARIES Linkinen, & Kaartinen & Linkinen, Lidman, Heinonen, Framing PremodernFraming Desires Edited by Satu Lidman, Meri Heinonen, Tom Linkinen, and Marjo Kaartinen Framing Premodern Desires Sexual Ideas, Attitudes, and Practices in Europe Framing Premodern Desires Crossing Boundaries Turku Medieval and Early Modern Studies The series from the Turku Centre for Medieval and Early Modern Studies (TUCEMEMS) publishes monographs and collective volumes placed at the intersection of disciplinary boundaries, introducing fresh connections between established fields of study. The series especially welcomes research combining or juxtaposing different kinds of primary sources and new methodological solutions to deal with problems presented by them. Encouraged themes and approaches include, but are not limited to, identity formation in medieval/early modern communities, and the analysis of texts and other cultural products as a communicative process comprising shared symbols and meanings. Series Editor Matti Peikola, Department of Modern Languages, University of Turku, Finland Editorial Board Janne Harjula, Adjunct Professor of Historical Archaeology, University of Turku Hemmo Laiho, Postdoctoral Researchers, Department of Philosophy, University of Turku Satu Lidman, Adjunct Professor of History of Criminal law, Faculty of Law/Legal History, University of Turku Aino Mäkikalli, Postdoctoral Researcher, Department of Comparative Literature, University of Turku Kirsi-Maria Nummila, Adjunct Professor of Finnish language, University of Turku; University Lecturer of Finnish, University of Helsinki Kirsi Salonen, Associate Professor, School of History, Culture and Arts Studies, University of Turku Kirsi Vainio-Korhonen, Professor of Finnish history, Department of Finnish His- tory, University of Turku Framing Premodern Desires Sexual Ideas, Attitudes, and Practices in Europe Edited by Satu Lidman, Meri Heinonen, Tom Linkinen, and Marjo Kaartinen Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: A brothel scenery, Joachim Beuckelaer (c. -

The Magistrate and the Community: Summary Proceedings in Rural England During the Long Eighteenth Century Creator: Darby, N

This work has been submitted to NECTAR, the Northampton Electronic Collection of Theses and Research. Thesis Title: The magistrate and the community: summary proceedings in rural England during the long eighteenth century Creator: Darby, N. E. C. R Example citation: Darby, N. E. C. (2015) The magistrate and the community: summary proceedings in rural England during the long eiAghteenth century. Doctoral thesis. The University of Northampton. Version: Accepted version T http://nectarC.northampton.ac.uk/9720/ NE The magistrate and the community: summary proceedings in rural England during the long eighteenth century Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy At the University of Northampton 2015 Nerys Elizabeth Charlotte Darby © Nell Darby 2015. This thesis is copyright material and no quotation from it may be published without proper acknowledgement Abstract The study of how the law worked at a local level in rural communities, and in the role of the rural magistrate at summary level, has been the subject of relatively little attention by historians. More attention has been given to the higher courts, when the majority of plebeian men and women who experienced the law during the long eighteenth century would have done so at summary level. Although some work has been carried out on summary proceedings, this has also tended to focus either on metropolitan records, a small number of sources, or on a specific, limited, number of offences. There has not been a broader study of rural summary proceedings to look at how the role and function of the rural magistrate, how local communities used this level of the criminal justice system, as complainants, defendants and witnesses, and how they negotiated their place in their local community through their involvement with the local magistrate. -

Ecclesiology in the Church of England: an Historical and Theological Examination of the Role of Ecclesiology in the Church of England Since the Second World War

Durham E-Theses Ecclesiology in the Church of England: an historical and theological examination of the role of ecclesiology in the church of England since the second world war Bagshaw, Paul How to cite: Bagshaw, Paul (2000) Ecclesiology in the Church of England: an historical and theological examination of the role of ecclesiology in the church of England since the second world war, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4258/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Ecclesiology in the Church of England: an historical and theological examination of the role of ecclesiology in the Church of England since the Second World War The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should i)C published in any form, including; Electronic and the Internet, without the author's prior written consent. -

Admission Criteria

Appendix 1 Cardiff Council: Admission Criteria October 2017 Professor Chris Taylor [email protected] Wales Institute of Social & Economic Research, Data & Methods (WISERD) 029 20876938 Cardiff University, School of Social Sciences @profchristaylor Table of Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................. 1 2. Context for admissions in Cardiff .......................................................................................................................... 2 3. Cardiff school admissions ......................................................................................................................................... 4 4. Analysis of Cardiff school admissions .................................................................................................................... 6 5. Review of other local authority admission arrangements .............................................................................. 16 6. School admissions research ................................................................................................................................... 21 6.1 Admission authorities............................................................................................................................................. 21 6.2 School preferences ................................................................................................................................................ -

Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document. MEASURING MARKETS: the CASE of the ERA 1988

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 464 199 UD 034 994 AUTHOR Fitz, John; Taylor, Chris; Gorard, Stephen; White, Patrick TITLE Local Education Authorities and the Regulation of Educational Markets: Four Case Studies. Measuring Markets: The Case of the ERA 1988. Occasional Paper. INSTITUTION Cardiff Univ. (Wales). School of Social Sciences. SPONS AGENCY Economic and Social Research Council, Lancaster (England). REPORT NO OP-41 ISBN ISBN-1-87-2330-460 PUB DATE 2001-00-00 NOTE 48p.; Some figures may not reproduce adequately. CONTRACT R000238031 AVAILABLE FROM For full text: http://www.cardiff.ac.uk/socsi/markets. PUB TYPE Reports Evaluative (142) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Access to Education; *Admission Criteria; *Admission (School); Case Studies; Educational Change; Educational Discrimination; Educational Policy; Foreign Countries; Free Enterprise System; *School Choice; Secondary Education IDENTIFIERS England; *Local Education Authorities (United Kingdom); Reform Efforts; Wales ABSTRACT This paper presents four case studies that are part of a larger study on admissions arrangements and impacts on school admissions for all local education authorities (LEAs) in England and Wales. It examines factors influencing the social composition of schools. A total of 23 LEAs completed interviews about their secondary school admissions arrangements The four case study LEAs have significantly different market scenarios. Results show that recent national education policy has not been evenly implemented across LEAs. A combination of organizational, structural, and demographic factors have muted much of the potential impact of school reforms on school admissions. Normative patterns of school use have not been substantially affected by the market reforms or the administrative actions of LEAs. LEAs remain important arenas within which school choice operates because they define kinds of choice available to parents in their administrative boundaries. -

Tamara Matheson

Chaplin Page 1 of 9 TAMARA CHAPLIN Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 309 Gregory Hall MC 466 810 South Wright Street Urbana, Illinois 61801 USA US Cell: 001 217 979 3990 / Email: [email protected] EMPLOYMENT 2008-present: Associate Professor of Modern European History, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC) Affilitated Faculty, Gender and Women’s Studies, UIUC Affiliated Faculty, Department of French and Italian, UIUC Associated Faculty, Unit for Criticism and Interpretive Theory Associated Faculty, European Union Center, UIUC Associated Faculty, Holocaust, Genocide and Memory Studies, UIUC 2002-2008: Assistant Professor of Modern European History, UIUC EDUCATION Ph.D. Modern European History, September 2002, Rutgers: The State University of NJ, New Brunswick, NJ, USA (1995-2002). Dissertation: “Embodying the Mind: French Philosophers on Television, 1951-1999” Advisors: Bonnie G. Smith (Director), Joan W. Scott, John Gillis, Herrick Chapman (NYU) Major Field: Modern Europe Minor Fields: Contemporary France/ Media History of Gender and Sexuality Cultural and Intellectual B.A. History, Honors with Great Distinction, September 1995, Concordia University, Montreal, Canada (1991-1995). FELLOWSHIPS AND AWARDS 2016 Summer NEH Summer Stipend ($6000 for June-July, 2016; book project on Desiring Women). 2016 Spring Camargo Foundation Fellowship, Cassis, France (housing, $1600 stipend, airfare). 2016 Spring Humanities Released Time, UIUC Research Board, Urbana, IL. 2015 Fall Zwickler Memorial Research Grant ($1350), Cornell University, NY. 2014 Summer Visiting Fellow, York University, York, England. 2014 Summer Provost’s Faculty Retreat Grant, UIUC, Urbana, IL http://wwihist258.weebly.com/ 2014 Spring UIUC Research Board Support: Research Assistant, UIUC, Urbana, IL. -

Courtesans in Colonial India Representations of British Power Through Understandings of Nautch-Girls, Devadasis, Tawa’Ifs, and Sex-Work, C

Courtesans in Colonial India Representations of British Power through Understandings of Nautch-Girls, Devadasis, Tawa’ifs, and Sex-Work, c. 1750-1883 by Grace E. S. Howard A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Grace E. S. Howard, May, 2019 ABSTRACT COURTESANS IN COLONIAL INDIA REPRESENTATIONS OF BRITISH POWER THROUGH UNDERSTANDINGS OF NAUTCH-GIRLS, DEVADASIS, TAWA’IF, AND SEX-WORK, C. 1750-1883 Grace E. S. Howard Advisors: University of Guelph Dr. Jesse Palsetia Dr. Norman Smith Dr. Kevin James British representations of courtesans, or nautch-girls, is an emerging area of study in relation to the impact of British imperialism on constructions of Indian womanhood. The nautch was a form of dance and entertainment, performed by courtesans, that originated in early Indian civilizations and was connected to various Hindu temples. Nautch performances and courtesans were a feature of early British experiences of India and, therefore, influenced British gendered representations of Indian women. My research explores the shifts in British perceptions of Indian women, and the impact this had on imperial discourses, from the mid-eighteenth through the late nineteenth centuries. Over the course of the colonial period examined in this research, the British increasingly imported their own social values and beliefs into India. British constructions of gender, ethnicity, and class in India altered ideas and ideals concerning appropriate behaviour, sexuality, sexual availability, and sex-specific gender roles in the subcontinent. This thesis explores the production of British lifestyles and imperial culture in India and the ways in which this influenced their representation of courtesans. -

Exeter Register Cover 2007

EXETER COLLEGE ASSOCIATION Register 2007 Contents From the Rector 6 From the President of the MCR 10 From the President of the JCR 12 Alan Raitt by David Pattison 16 William Drower 18 Arthur Peacocke by John Polkinghorne 20 Hugh Kawharu by Amokura Kawharu 23 Peter Crill by Godfray Le Quesne 26 Rodney Hunter by Peter Stone 28 David Phillips by Jan Weryho 30 Phillip Whitehead by David Butler 34 Ned Sherrin by Tony Moreton 35 John Maddicott by Paul Slack and Faramerz Dabhoiwala 37 Gillian Griffiths by Richard Vaughan-Jones 40 Exeter College Chapel by Helen Orchard 42 Sermon to Celebrate the Restoration of the Chapel by Helen Orchard 45 There are Mice Throughout the Library by Helen Spencer 47 The Development Office 2006-7 by Katrina Hancock 50 The Association and the Register by Christopher Kirwan 51 A Brief History of the Exeter College Development Board by Mark Houghton-Berry 59 Roughly a Hundred Years Ago: A Law Tutor 61 Aubrey on Richard Napier (and his Nephew) 63 Quantum Computing by Andrew M. Steane 64 Javier Marías by Gareth Wood 68 You Have to Be Lucky by Rip Bulkeley 72 Memorabilia by B.L.D. Phillips 75 Nevill Coghill, a TV programme, and the Foggy Foggy Dew by Tony Moreton 77 The World’s First Opera by David Marler 80 A Brief Encounter by Keith Ferris 85 College Notes and Queries 86 The Governing Body 89 Honours and Appointments 90 Publications 91 Class Lists in Honour Schools and Honour Moderations 2007 94 Distinctions in Moderations and Prelims 2007 96 1 Graduate Degrees 2007 97 College Prizes 99 University Prizes 100 Graduate Freshers 2007 101 Undergraduate Freshers 2007 102 Deaths 105 Marriages 107 Births 108 Notices 109 2 Editor Christopher Kirwan was Fellow and Lecturer in Philosophy from 1960 to 2000. -

The Cardiff High School Partnership 29

Address: Cardiff High School Llandennis Road Useful Contacts Cyncoed Cardiff CF23 6WG Achievement Leaders Y7 Mrs B. Jones ([email protected]) Y8 Mr. M. O’Brien (Acting) Telephone: ([email protected]). 029 20 757 741 Fax: Y9 Mrs. S. Crossan ([email protected]) 029 20 680 850 Y10 Mr. M. Olsen ([email protected]) Y11 Mr. D. Rhodes ([email protected]) Y12 Mrs. G. Olsen ([email protected]) Y13 Mrs. M. Griffiths ([email protected]) Website: Heads of School www.cardiffhigh.co.uk Lower School Mr. G. Jones ([email protected]) Middle School (Acting) To Be Confirmed Upper School Follow CHS and also Mr. D. Leggett ([email protected]) individual departments and groups on twitter Deputy Headteacher - Wellbeing & Achievement Search for @officialCHS Mrs. A. Yarrow ([email protected]) Headteacher’s Personal Assistant Mrs. H. Richards ([email protected]) Like us on facebook Search for @officialCHS ParentMail & Text Alerts Sign up for Parent Mail to get instant updates of important school information or details about school events. See the link on the school website for more information. 2 Welcome I am delighted that you have chosen Cardiff High School for the next stage of your child’s education, and I am looking forward to working closely with you over the coming months and years. In the last year we have entered an exciting new phase of development for Cardiff High School, which we believe has further enhanced the School’s reputation for excellence. -

Newsletter Dec 2016

Brynmawr Foundation School DecemberBrynmawr 2016 Newsletter Foundation School Ysgol Sylfaenol Brynmawr December 2016 Newsletter Dear Parent, Time this year has flown by but the year so far has been packed full of achievements born from the efforts of our students, staff and school community. Every day I continue to be inspired by the students and my colleagues and all that they do together to make Brynmawr Foundation School special, unique and outstanding. All the activities and achievements since September continue to highlight how impressive our students are and the energy, talent, enthusiasm and commitment they bring to our school, Dates for your Diary illustrating the continued dedication of all our staff I am proud of the commitment our students have shown in December representing their school when on trips and also at events in 15th – End of Term the school. 16th – INSET Day For some families, of course, Christmas does not bring the joy January and happiness with which others are so blessed. With this in 3rd – Start of Spring Term mind I am extremely proud of our pupils and their efforts in 19th – Year 9/10 Options Evening raising money for charity including, once again, a significant th amount of money to buy presents for the Barnardo’s appeal. 25 – 6pm Year 11 Prom Catwalk Show Our focus in January continues to be student progress and ensuring that students are positively engaged with their February learnin g. We have had over 200 applicants for a maximum 151 7th – 9th School Production entry in September 2017. Staff have maintained incredibly 15th – Year 11 Parents Evening high standards as a team, so that all functions of the school 16th – 20th Florida Trip are focused on supporting the students’ learning and progress.