Blister Beetles in Alfalfa Circular 536 Revised by Jane Breen Pierce1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poxviruses: Smallpox Vaccine, Its Complications and Chemotherapy

Virus Adaptation and Treatment Dovepress open access to scientific and medical research Open Access Full Text Article R E V IEW Poxviruses: smallpox vaccine, its complications and chemotherapy Mimi Remichkova Abstract: The threat of bioterrorism in the recent years has once again posed to mankind the unresolved problems of contagious diseases, well forgotten in the past. Smallpox (variola) is Department of Pathogenic Bacteria, The Stephan Angeloff Institute among the most dangerous and highly contagious viral infections affecting humans. The last of Microbiology, Bulgarian Academy natural case in Somalia marked the end of a successful World Health Organization campaign of Sciences, Sofia, Bulgaria for smallpox eradication by vaccination on worldwide scale. Smallpox virus still exists today in some laboratories, specially designated for that purpose. The contemporary response in the treatment of the post-vaccine complications, which would occur upon enforcing new programs for mass-scale smallpox immunization, includes application of effective chemotherapeutics and their combinations. The goals are to provide the highest possible level of protection and safety of For personal use only. the population in case of eventual terrorist attack. This review describes the characteristic features of the poxviruses, smallpox vaccination, its adverse reactions, and poxvirus chemotherapy. Keywords: poxvirus, smallpox vaccine, post vaccine complications, inhibitors Characteristics of poxviruses Smallpox (variola) infection is caused by the smallpox virus. This virus belongs to the genus of Orthopoxvirus included in the Poxviridae family. Poxviruses are one of the largest and most complexly structured viruses, known so far. The genome of poxviruses consists of a linear two-chained DNA and its replication takes place in the cytoplasm of the infected cell. -

Elytra Reduction May Affect the Evolution of Beetle Hind Wings

Zoomorphology https://doi.org/10.1007/s00435-017-0388-1 ORIGINAL PAPER Elytra reduction may affect the evolution of beetle hind wings Jakub Goczał1 · Robert Rossa1 · Adam Tofilski2 Received: 21 July 2017 / Revised: 31 October 2017 / Accepted: 14 November 2017 © The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract Beetles are one of the largest and most diverse groups of animals in the world. Conversion of forewings into hardened shields is perceived as a key adaptation that has greatly supported the evolutionary success of this taxa. Beetle elytra play an essential role: they minimize the influence of unfavorable external factors and protect insects against predators. Therefore, it is particularly interesting why some beetles have reduced their shields. This rare phenomenon is called brachelytry and its evolution and implications remain largely unexplored. In this paper, we focused on rare group of brachelytrous beetles with exposed hind wings. We have investigated whether the elytra loss in different beetle taxa is accompanied with the hind wing shape modification, and whether these changes are similar among unrelated beetle taxa. We found that hind wings shape differ markedly between related brachelytrous and macroelytrous beetles. Moreover, we revealed that modifications of hind wings have followed similar patterns and resulted in homoplasy in this trait among some unrelated groups of wing-exposed brachelytrous beetles. Our results suggest that elytra reduction may affect the evolution of beetle hind wings. Keywords Beetle · Elytra · Evolution · Wings · Homoplasy · Brachelytry Introduction same mechanism determines wing modification in all other insects, including beetles. However, recent studies have The Coleoptera order encompasses almost the quarter of all provided evidence that formation of elytra in beetles is less currently known animal species (Grimaldi and Engel 2005; affected by Hox gene than previously expected (Tomoyasu Hunt et al. -

BLISTER BEETLES in ALFALFA L.Ee Townsend, Extension Entomologist

U N I V E R S I T Y O F K E N T U C K Y COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE DEPARTMENT OF ENTOMOLOGY ENTFACT-102 BLISTER BEETLES IN ALFALFA L.ee Townsend, Extension Entomologist Several of the common members of this group of Female blister beetles lay clusters of eggs in the soil in beetles contain a chemical that often causes blisters late summer. The small, active larvae that hatch from when applied to the skin; thus the name blister beetles. these eggs crawl over the soil surface entering cracks The substance can be toxic to animals that eat a in search for grasshopper egg pods which are deposited sufficient amount. An understanding of the insects and in the soil. After finding the eggmass, blister beetle their life cycles allows sound management practices to larvae become immobile and spend the rest of their minimize the chances of trapping beetles in hay. It also developmental time as legless grubs. The following gives horse and livestock owners information to summer they transform into the pupal stage and soon consider when making hay purchases. One major emerge in the adult stage. This is why blister beetle factor that increases potential for blister beetle numbers increase dramatically following high problems is crimping hay. This crushes the beetles and grasshopper populations. leaves them in the hay where they can be eaten by animals. The second factor is a large increase in Blister Beetle Toxicity grasshopper numbers. The larval stages of these blister Cantharidin is the poisonous substance in blister beetles develop on grasshopper egg pods in the soil. -

Cytogenetic Analysis, Heterochromatin

insects Article Cytogenetic Analysis, Heterochromatin Characterization and Location of the rDNA Genes of Hycleus scutellatus (Coleoptera, Meloidae); A Species with an Unexpected High Number of rDNA Clusters Laura Ruiz-Torres, Pablo Mora , Areli Ruiz-Mena, Jesús Vela , Francisco J. Mancebo , Eugenia E. Montiel, Teresa Palomeque and Pedro Lorite * Department of Experimental Biology, Genetics Area, University of Jaén, 23071 Jaén, Spain; [email protected] (L.R.-T.); [email protected] (P.M.); [email protected] (A.R.-M.); [email protected] (J.V.); [email protected] (F.J.M.); [email protected] (E.E.M.); [email protected] (T.P.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Simple Summary: The family Meloidae contains approximately 3000 species, commonly known as blister beetles for their ability to secrete a substance called cantharidin, which causes irritation and blistering in contact with animal or human skin. In recent years there have been numerous studies focused on the anticancer action of cantharidin and its derivatives. Despite the recent interest in blister beetles, cytogenetic and molecular studies in this group are scarce and most of them use only classical chromosome staining techniques. The main aim of our study was to provide new information in Citation: Ruiz-Torres, L.; Mora, P.; Meloidae. In this study, cytogenetic and molecular analyses were applied for the first time in the Ruiz-Mena, A.; Vela, J.; Mancebo, F.J.; family Meloidae. We applied fluorescence staining with DAPI and the position of ribosomal DNA in Montiel, E.E.; Palomeque, T.; Lorite, P. Hycleus scutellatus was mapped by FISH. Hycleus is one of the most species-rich genera of Meloidae Cytogenetic Analysis, but no cytogenetic data have yet been published for this particular genus. -

Lytta Vesicatoria) Dermatitis Outbreak and Containment at Kwara State University Students’ Hostels Adeyemi Mufutau AJAO*1 Oluwasogo A

Scholars Journal of Applied Medical Sciences (SJAMS) ISSN 2320-6691 (Online) Sch. J. App. Med. Sci., 2016; 4(2B):460-468 ISSN 2347-954X (Print) ©Scholars Academic and Scientific Publisher (An International Publisher for Academic and Scientific Resources) www.saspublisher.com Original Research Article Investigation of Blister Beetle (Lytta vesicatoria) Dermatitis Outbreak and Containment at Kwara State University Students’ Hostels Adeyemi Mufutau AJAO*1 Oluwasogo A. OLALUBI2, Ismaila, Adeniran ADEROLU3, Shola. K BABATUNDE1, Nimat B. IDRIS4, Abdulrasheed Abidemi ADIO2, E.B AJAO4 1Department of Bioscience and Biotechnology, Kwara State University, Nigeria 2School of Allied Health & Environmental Scieces, 3Department of Crop production, 4Medical Centre and Environment Safety Unit, Kwara State University, Malete. PMB 1533, Ilroin, Kwara State, Nigeria *Corresponding author Adeyemi Mufutau AJAO Email: [email protected] Abstract: The study was undertaken to ascertain the causative agent and diagnosis of the clinical profile of patients that made them susceptible to Blister Beetle Dermatitis, efforts were also devoted to investigate risk factors associated with BBD symptoms in patients. This study also provides entomological and environmental data on occurrence and outbreak of BBD at the student hostels in Kwara State University, Nigeria. Patients with clinical manifestation of dermatitis were studied by questionnaire administration along with close clinical examination of the disease condition. The questionnaire sought information on skin lesions, sleeping locations of the patients and beetle activity. The result of the study revealed 44 patients (30 males and 14 females) reported insect bite, dermatitis at and were treated for BBD at the University Medical Centre. The majority of patients were in the age group 10-25years, (77.3%). -

Identification of New Cantharidin Derivatives As

IDENTIFICATION OF NEW CANTHARIDIN DERIVATIVES AS NOVEL POTENTIAL INHIBITORS OF PROTEIN PHOSPHATASES 2 AND 5 (PP2A, PP5) Olga Balabon, Dariia Samofalova Life Chemicals Europe GmbH, Leonhardsweg 2, 82008 Unterhaching, Germany. e-mail: [email protected] Cantharidin, a natural compound occurring in medicinal insect blister beetle (Mylabris phalerata Pallas), The docking results showed that three amino acid and its water-soluble demethylated synthetic analog norcantharidin (better known as endothall), residues, Arg275, Asn303, His304, and Arg275, His304, historically used in the purification of phosphorylated proteins, were identified as inhibitors of Arg400 (PP5 and PP2A, respectively) were the most serine-threonine protein phosphatases (PP). Cantharidin (CID 5944, hydrolyzing into cathartic acid important for the ligand binding. In total, nine residues were demonstrated to be involved in the binding - CID 2544) is a potent selective inhibitor of PP2A and PP5 [PMID: 1334551], while of the inhibitors. The completeness of the amino norcantharidin (CID 93004) is a medium-strength inhibitor of PP2A only acid sequence and the profile of the site interaction [PMID:12003183, 23809227]. These compounds have extensively been studied as promising leads in were determined by pairwise and profile alignment with the development of more effective therapeutics for the treatment of cancer, the original sequence (with ClustalX). The binding site neurodegenerative disorders, and type 1 diabetes mellitus. As no highly PP5 selective inhibitors for -

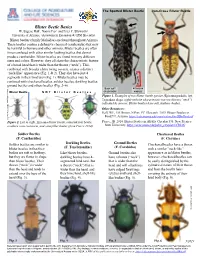

Blister Beetle Basics W

The Spotted Blister Beetle Iron-Cross Blister Beetle Blister Beetle Basics W. Eugene Hall1, Naomi Pier1 and Peter C. Ellsworth2 University of Arizona, 1Assistants in Extension & 2IPM Specialist Blister beetles (family Meloidae) are found throughout Arizona. These beetles contain a defensive chemical (cantharidin) that may be harmful to humans and other animals. Blister beetles are often times confused with other similar looking beetles that do not produce cantharidin. Blister beetles are found in many different sizes and colors. However, they all share the characteristic feature of a broad head that is wider than the thorax (“neck”). This, combined with broader elytra (wing covers), creates a distinct “neck-like” appearance (Fig. 1 & 2). They also have just 4 1 segments in their hind tarsi (Fig. 1). Blister beetles may be 2 confused with checkered beetles, soldier beetles, darkling beetles, 3 4 Figureground 8G. Adult beetles blister beetle, and Zonitis others atripennis beetles. (Fig.Figure 8H 2. –Adult6). blister beetle, Zonitis sayi. (Whitney (WhitneySandya Cranshaw, Colorado State University, Bugwood.org) Cranshaw, Colorado State University, Bugwood.org) BODY SOFT 4 TARSI IN Blister Beetle NOT Blister Beetles OR LEATHERY HINDLEG Athigiman Figure 1. Examples of two blister beetle species (Epicauta pardalis, left; Tegrodera aloga, right) with the characteristic narrow thorax (“neck”) , NMSU, Circular 536 Circular , NMSU, indicated by arrows. Blister beetles have soft, leathery bodies. Other Resources: Hall, WE, LM Brown, N Pier, PC Ellsworth. 2019. Blister Beetles in Food? U. Arizona. https://cals.arizona.edu/crops/cotton/files/BBinFood.pdf Figure 2. Left to right, Epicauta blister beetle, tamarisk leaf beetle, Pierce, JB. -

Sperm Cells of a Primitive Strepsipteran

Insects 2013, 4, 463-475; doi:10.3390/insects4030463 OPEN ACCESS insects ISSN 2075-4450 www.mdpi.com/journal/insects/ Article Sperm Cells of a Primitive Strepsipteran James B. Nardi 1,*, Juan A. Delgado 2, Francisco Collantes 2, Lou Ann Miller 3, Charles M. Bee 4 and Jeyaraney Kathirithamby 5 1 Department of Entomology, University of Illinois, 320 Morrill Hall, 505 S. Goodwin Avenue, Urbana, IL 61801, USA 2 Department of Zoology and Physical Anthropology, Faculty of Biology, University of Murcia, Murcia 30100, Spain; E-Mails: [email protected] (J.A.D.); [email protected] (F.C.) 3 Biological Electron Microscopy, Frederick Seitz Materials Research Laboratory, Room 125, University of Illinois, 104 South Goodwin Avenue, Urbana, IL 61801, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 4 Imaging Technology Group, Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology, University of Illinois, 405 N. Mathews Avenue, Urbana, IL 61801, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 5 Department of Zoology, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3PS, UK; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-217-333-6590; Fax: +1-217-244-3499. Received: 1 July 2013; in revised form: 7 August 2013 / Accepted: 15 August 2013 / Published: 4 September 2013 Abstract: The unusual life style of Strepsiptera has presented a long-standing puzzle in establishing its affinity to other insects. Although Strepsiptera share few structural similarities with other insect orders, all members of this order share a parasitic life style with members of two distinctive families in the Coleoptera²the order now considered the most closely related to Strepsiptera based on recent genomic evidence. -

Blister Beetles (Insecta: Coleoptera: Meloidae)1 Richard B

EENY166 Blister Beetles (Insecta: Coleoptera: Meloidae)1 Richard B. Selander and Thomas R. Fasulo2 Introduction blister beetles are seldom seen, except for first instar larvae (triungulins) frequenting flowers or clinging to adult The family Meloidae, the blister beetles, contains about bees. All blister beetle larvae are specialized predators. 2500 species, divided among 120 genera and four subfami- Larvae of most genera enter the nests of wild bees, where lies (Bologna and Pinto 2001). Florida has 26 species, only they consume both immature bees and the provisions a small fraction of the total number in the US, but nearly of one or more nest cells. The larvae of some Meloinae, three times that of the West Indies (Selander and Bouseman including most Epicauta spp., prey on the eggs of acridid 1960). Adult beetles are phytophagous, feeding especially grasshoppers. A few larvae evidently prey on the eggs of on plants in the families Amaranthaceae, Asteraceae, blister beetles (Selander 1981). Of the Florida species, Fabaceae, and Solanaceae. Most adults eat only floral parts, Nemognatha punctulata LeConte (misidentified as Zonitis but some, particularly those of Epicauta spp., eat leaves as vittigera (LeConte)) has been found in a nest of a Megachile well. sp. in Cuba (Scaramuzza 1938) and several members of the genus Epicauta have been associated with the eggpods of Melanoplus spp. Figure 1. Adult Epicauta floridensis Werner (left), and E. cinerea Forster (right). Credits: Lyle J. Buss, University of Florida A few adults are nocturnal, but most are diurnal or show no distinct diel cycle. Since adults are gregarious and often Figure 2. -

Wöhler Synthesis of Urea

Wöhler synthesis of urea Wöhler, 1928 – – + + NH Cl + K N C O 4 NH4 N C O O H2N NH2 Friedrich Wöhler Annalen der Physik und Chemie 1828, 88, 253–256 Significance: Wöhler was the first to make an organic substance from an inorganic substance. This was the beginning of the end of the theory of vitalism: the idea that organic and inorganic materials differed essentially by the presence of the “vital force”– present only in organic material. To his mentor Berzelius:“I can make urea without thereby needing to have kidneys, or anyhow, an animal, be it human or dog" Friedrich Wöhler, 1880-1882 Polytechnic School in Berlin Support for vitalism remained until 1845, when Kolbe synthesized acetic acid Polytechnic School at Kassel from carbon disulfide University of Göttingen Fischer synthesis of glucose PhHN N O N O NHPh Br aq. HCl Δ PhNH2NH2 HO H HO H O Br "α−acrose" H OH H OH H OH H OH CH2OH CH2OH α−acrosazone α−acrosone an “osazone” (osazone test for reducing sugars) Zn/AcOH OH OH CO2H CHO O HO H HO H OH Br2 HO H HO H Na-Hg HO H HNO3 HO H H OH H OH H OH H OH then resolve H O+ H OH via strychnine H OH H OH 3 H OH CH2OH salts CH2OH CH OH CH2OH 2 D-Mannonic acid DL-Mannose DL-Mannitol DL-Fructose quinoline • Established stereochemical relationship CO2H CHO H OH H OH between mannose and glucose Na-Hg HO H HO H (part of Fischer proof) H OH + H OH H3O • work mechanisms from acrosazone on H OH H OH Emil Fischer, 1852-1919 CH2OH CH2OH University of Munich (1875-81) D-Gluconic acid D-Glucose University of Erlangen (1881-88) University of Würzburg (1888-92) University of Berlin (1892-1919) Fischer, E. -

Use of Cantharidin for Verruca

CHA PT ER 4 USE OF CANTHARIDIN FOR VERRUCA Mickey D. Stapp, DPM HISTORY MECHANISM OF ACTION Cantharidin has been used for more than 2,000 years in Cantharidin is a vesicant produced by beetles belonging to both folk and traditional medicine. It was used in China the order of Coleoptera and the family of Meloidae. for many medicinal purposes including furuncles, ulcers, and Cantharidin used medically is collected from species of the tuberculosis, topically, and for abdominal masses, rabies, and genera Mylabris and Lytta, especially Lytta vesicatoria, as an anticancer agent, orally. In Europe, it appeared in better known as “Spanish Fly.” The male blister beetle Materia Medica, a medical monograph written in 50 to produces the substance, giving the chemical to the female 100 AD. Hippocrates prescribed cantharidin as a treatment during mating. Afterwards the female beetle will cover its for dropsy (1). eggs with the chemical as a defense against predators (6). Cantharidin has a long infamous reputation for being Cantharidin acts as a blistering agent or acantholytic. an aphrodisiac and is known as Spanish fly. This reputation The lipid layers of epidermal cell membranes absorb it. Once is based on the observation of pelvic congestion in women applied, cantharidin causes release of neutral serine proteases and priapism in men after cantharidin ingestion. It is not that cause degeneration of the desmosmal plaque, leading a true aphrodisiac, and fatal poisonings can occur (2). to detachment of tonofilaments from desmosomes (7). This Cantharidin has also been used as a homicidal agent in leads to intraepidermal blistering and nonspecific lysis of the South Africa. -

Proceedings of the United States National Museum

Proceedings of the United States National Museum SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION • WASHINGTON, D.C. Volume 111 1960 Number 342f MELOID BEETLES (COLEOPTERA) OF THE WEST INDIES By Richard B. Selander and John K. Bouseman' Introduction The West Indies have never received attention from entomologists commensurate with their great biogeographical interest. Descriptions of West Indian species of Meloidae have appeared at irregular inter- vals since the fu'st species was described by Fabricius in 1781, but no attempt has been made to treat these beetles comprehensively or to relate them to the beetle fauna of the American mainland. We there- fore feel that the present report will be valuable, for by bringing together all available information on the Meloidae of the West Indies, the report will not only serve as a means of identifying the species of the islands but will perhaps also stimulate more widespread interest in the meloid fauna, so that the process of studying and interpreting it will be accelerated. For the purpose of this report the West Indies are defined as includ- ing the Bahama Islands, the Greater Antilles, and the Lesser Antilles as far south as Grenada. Trinidad and the other islands associated with it along the northern coast of South America, while forming pan of the West Indies in the physiographic sense, are excluded because they are on biogeographic grounds more logically treated as part of South America. > A joint contribution of the Department of Entomology of the University of Illinois, and the Section of Faunlstic Surveys and Insect Identification of the Illinois Natural History Survey. 197 198 PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL MUSEUM Origin The meloid fauna of the West Indies is known to inckide 9 species m 5 genera,: Meloe, Tetraonyx, Cissites, Pseudozonitis, and Nemognatha.