Gordon Mumma Music for Solo Piano 1960–2001

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Live-Electronic Music

live-Electronic Music GORDON MUMMA This b()oll br.gills (lnd (')uis with (1/1 flnO/wt o/Ihe s/u:CIIlflli01I$, It:clmulogira{ i,m(I1M/;OIn, find oC('(uimwf bold ;lIslJiraliml Iltll/ mm"k Ihe his lory 0/ ciec/muir 111111';(", 8u/ the oIJt:ninf!, mui dosing dlll/J/er.f IIr/! in {art t/l' l)I dilfcl'CIIt ltiJ'ton'es. 0110 Luerd ng looks UfI("/,- 1,'ulIl Ihr vll l/laga poillt of a mnn who J/(u pel'smlfl.lly tui(I/I'sscd lite 1)Inl'ch 0/ t:lcrh'Ollic tccJlIlulogy {mm II lmilll lIellr i/s beg-ilmings; he is (I fl'ndj/l(lnnlly .~{'hooletJ cOml)fJj~l' whQ Iws g/"lulll/llly (lb!Jfll'ued demenls of tlli ~ iedmoiQI!J' ;11(0 1111 a/rc(uiy-/orllleti sCI al COlli· plJSifion(l/ allillldes IInti .rki{l$. Pm' GarrlOll M umma, (m fllr. other IWfI((, dec lroll;c lerllll%gy has fllw/lys hetl! pre.telll, f'/ c objeci of 01/ fl/)sm'uillg rlln'osily (mrl inUre.fI. lu n MmSI; M 1I11111W'S Idslur)l resltllle! ",here [ . IIt:1lillg'S /(.;lIve,( nff, 1',,( lIm;lI i11g Ihe dCTleiojJlm!lIls ill dec/m1/ ;,. IIII/sir br/MI' 19j(), 1101 ~'/J IIIlIrli liS exlell siom Of $/ili em'fier lec1m%gicni p,"uedcnh b111, mOw,-, as (upcclS of lite eCQllol/lic lind soci(ll Irislm)' of the /.!I1riotl, F rom litis vh:wJ}f)il1/ Ite ('on,~i d ".r.f lHU'iQII.f kint/s of [i"t! fu! r/urmrl1lcI' wilh e/cclnmic medifl; sl/)""m;ys L'oilabomlive 1>t:rformrl1lce groU/JS (Illd speril/f "heme,f" of cIIgilli:C'-;lIg: IUltl ex/,/orcs in dt:lllil fill: in/tulmet: 14 Ihe new If'dllllJiolO' 011 pop, 10/1(, rock, nllrl jllu /Ill/SIC llJi inJlnwu:lI/s m'c modified //till Ille recording studio maltel' -

David Tudor: Live Electronic Music

LMJ14_001- 11/15/04 9:54 AM Page 106 CD COMPANION INTRODUCTION David Tudor: Live Electronic Music The three pieces on the LMJ14 CD trace the development of David Tudor’s solo electronic music during the period from 1970 to 1984. This work has not been well docu- mented. Recordings of these pieces have never before been released. The three pieces each represent a different collaboration: with Experiments in Art and Technology (EAT), with the Merce Cunningham Dance Company (MCDC) and with Jacqueline Matisse Monnier [1]. The CD’s cover image, Toneburst Map 4, also arises from a collaboration, with the artist Sophia Ogielska. Anima Pepsi (1970) was composed for the pavilion designed by EAT for the 1970 Expo in Osaka, Japan. The piece made extensive use of a processing console consisting of eight identi- cal processors designed and built by Gordon Mumma and a spatialization matrix of 37 loud- speakers. Each processor consisted of a filter, an envelope follower, a ring modulator and a voltage-controlled amplifier. Anima Pepsi used this processing capability to transform a library of recordings of animal and insect sounds together with processed recordings of similar sources. Unlike most of Tudor’s solo electronics, this piece was intended to be performed by other members of the EAT collective, a practical necessity as the piece was to be performed repeatedly as part of the environment of the pavilion for the duration of the exposition. Toneburst (1975) was commissioned to accompany Merce Cunningham’s Sounddance. This recording is from a performance by MCDC, probably at the University of California at Berke- ley, where MCDC appeared fairly regularly. -

Holmes Electronic and Experimental Music

C H A P T E R 3 Early Electronic Music in the United States I was at a concert of electronic music in Cologne and I noticed that, even though it was the most recent electronic music, the audience was all falling asleep. No matter how interesting the music was, the audience couldn’t stay awake. That was because the music was coming out of loudspeakers. —John Cage Louis and Bebe Barron John Cage and The Project of Music for Magnetic Tape Innovation: John Cage and the Advocacy of Chance Composition Cage in Milan Listen: Early Electronic Music in the United States The Columbia–Princeton Electronic Music Center The Cooperative Studio for Electronic Music Roots of Computer Music Summary Milestones: Early Electronic Music of the United States Plate 3.1 John Cage and David Tudor, 1962. (John Cage Trust) 80 EARLY HISTORY – PREDECESSORS AND PIONEERS Electronic music activity in the United States during the early 1950s was neither organ- ized nor institutional. Experimentation with tape composition took place through the efforts of individual composers working on a makeshift basis without state support. Such fragmented efforts lacked the cohesion, doctrine, and financial support of their Euro- pean counterparts but in many ways the musical results were more diverse, ranging from works that were radically experimental to special effects for popular motion pictures and works that combined the use of taped sounds with live instrumentalists performing on stage. The first electronic music composers in North America did not adhere to any rigid schools of thought regarding the aesthetics of the medium and viewed with mixed skepticism and amusement the aesthetic wars taking place between the French and the Germans. -

Electronic Music

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The Research Repository @ WVU (West Virginia University) Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2018 Rethinking Interaction: Identity and Agency in the Performance of “Interactive” Electronic Music Jacob A. Kopcienski Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the Musicology Commons, and the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Kopcienski, Jacob A., "Rethinking Interaction: Identity and Agency in the Performance of “Interactive” Electronic Music" (2018). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 7493. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/7493 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rethinking Interaction: Identity and Agency in the Performance of “Interactive” Electronic Music Jacob A. Kopcienski Thesis submitted To the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Musicology Travis D. -

Gordon Mumma Was Born in 1935 in Framingham, Massachusetts. He

Gordon Mumma was born in 1935 in Framingham, Massachusetts. He studied piano and horn in Chicago and Detroit, and his early performing career was as a horn player in classical symphonic and chamber music. In 1952 he entered the University of Michigan, where he engaged with the group of young composers in the class of Ross Lee Finney. In Ann Arbor he co-founded with Robert Ashley the Cooperative Studio for Electronic Music (1958–66), and again with Ashley collaborated in Milton Cohen’s Space Theatre (1957–64) along with a group of uniquely creative individuals in art, architecture, and film. Mumma was one of the organizers of the historic ONCE Festival (1961–66), which made Ann Arbor an important site for the performance of innovative new music. The Ann Arbor years demonstrate the early significance of collaboration in Mumma’s creative process. Working connections with other musicians and artists in many disciplines—especially dance and film—have inspired and nourished much of his work as a composer, performer, instrument builder, and electronics wizard. From 1966 to 1974 he was, with John Cage and David Tudor, one of the composer-musicians with the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, for which he composed four commissioned works, including Mesa (1966) and Telepos (1971), and worked closely with Cunningham on his solo choreography for Loops (1971). During those years he also performed in the Sonic Arts Union with Robert Ashley, David Behrman, and Alvin Lucier. He has collaborated with such diverse artists as Tandy Beal, Anthony Braxton, Fred Frith, Pauline Oliveros, Yvonne Rainer, Tom Robbins, Stan VanDerBeek, and Christian Wolff. -

Interactive Electroacoustics

Interactive Electroacoustics Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Jon Robert Drummond B.Mus M.Sc (Hons) June 2007 School of Communication Arts University of Western Sydney Acknowledgements Page I would like to thank my principal supervisor Dr Garth Paine for his direction, support and patience through this journey. I would also like to thank my associate supervisors Ian Stevenson and Sarah Waterson. I would also like to thank Dr Greg Schiemer and Richard Vella for their ongoing counsel and faith. Finally, I would like to thank my family, my beautiful partner Emma Milne and my two beautiful daughters Amelia Milne and Demeter Milne for all their support and encouragement. Statement of Authentication The work presented in this thesis is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, original except as acknowledged in the text. I hereby declare that I have not submitted this material, either in full or in part, for a degree at this or any other institution. …………………………………………… Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ..................................................................................................................I LIST OF TABLES..........................................................................................................................VI LIST OF FIGURES AND ILLUSTRATIONS............................................................................ VII ABSTRACT..................................................................................................................................... X CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION............................................................................................. -

View PDF Document

THE AMERICAN SOCIETY NEWS LEITER OF UNIVERSITY COMPOSERS SPRING-SUMMER, 1977/V1. 10, Nos. 1-2 1977 NATIONAL CONFERENCE IN URBANA Symphony" andLanyAustin's "Second Fantasy on Ives' 'Universe Symphony'" was delivered. In another room at The Twelfth Annual Conference of the American the same time a discussion with Fred Koenigsberg, Legal Society of University Composers was held in Champaign Staff of ASCAP; concerning "Thoughts on the New Urbana from March 3rd to the 7th, 1977. The Copyright Law" was held. These were followed by a well-attended event, boasting 160 Society members, was "Lecture-Concert-Demonstration on the Contemporary hosted by the University of Illinois. For its gracious Flute" by Robert Aitken (University of Toronto). One of hospitality, many thanks are extended to the host institu the tone-setting highlights of the conference was a lively tion and its representatives. Those of us· who attended presentation-discussion on "Music Criticism." Arranged i were impressed and delighted by the Krannert Center for and introduced by Randolph Coleman (Oberlin College), I ! the Performing Arts. The excellent acoustics of the many the panel included Herbert Brun (University of Illinois), !' theaters augmented the quality performances. Special Larry Austin (University of Southern Florida), Tom accolades must be offered for the successful planning of Johnson (critic, The Village Voice), and Hans G. Helms this smoothly run conference to program chairman (West German Radio-Television and Public Broad Randolph Coleman (Oberlin College) and conference casting System). A refreshing break at the Levis Center committee chairman Edwin London (University of concluded the afternoon session. Illinois). They were assisted by the local members of the The evening concert, featuring the Illinois Women's conference committee: Alfred Blatter, Ben Johnston, Glee Club, University Chorale, Wind Ensemble, and John Melby, Tom Yarber, and Paul Zonn. -

Gordon Mumma Witchcraft, Cybersonlcs, Folkloric Virtuosity

Gordon Mumma Witchcraft, Cybersonlcs, Folkloric Virtuosity In the 18th Century a mechanical landscape-automaton, the Jacquet-Droz grotto, was exhibited throughout Europe. Approximately one meter square in area, it was an exceptional example of complex clockwork art. The clockwork landscape con taining grazing cattle and sheep, singing birds and barking dogs, flowing streams and fountains and people in promenade. The sun and moon followed their exact daily paths. Like Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, who was also a travelling performer in Europe at that time, the Jacquet-Droz grotto was a celebrated entertainment. However, when the grotto travelled to Spain it was confiscated by the Spanish authorities and destroyed. It was considered to be a deamonic manifestation, a threat not only to the church but a danger to the culture of Spain. The Spanish of the time were also settling in the New World and establishing reli gious missions in California. The spiritual influence of that early Spanish culture is still important in California. It is now mixed with the spiritual ways of the indigenous indians and the immigrant Asians and European Protestants. Witch craft and occultism are part of the spiritual ambience, and sometimes the political manifestations of California. I have been in Northern California this past year, establishing contemporary performance arts activities at the new University of California at Santa Cruz. Santa Cruz is an incredibly beautiful part of California, in an area of giant, ancient Redwood trees overlooking Monterey Bay on the Pacific Ocean. My collaborators in the project include the composer and musicologist William Brooks, students at the University, and people from the surrounding community. -

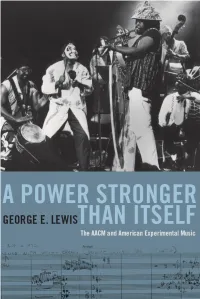

A Power Stronger Than Itself

A POWER STRONGER THAN ITSELF A POWER STRONGER GEORGE E. LEWIS THAN ITSELF The AACM and American Experimental Music The University of Chicago Press : : Chicago and London GEORGE E. LEWIS is the Edwin H. Case Professor of American Music at Columbia University. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2008 by George E. Lewis All rights reserved. Published 2008 Printed in the United States of America 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 1 2 3 4 5 ISBN-13: 978-0-226-47695-7 (cloth) ISBN-10: 0-226-47695-2 (cloth) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lewis, George, 1952– A power stronger than itself : the AACM and American experimental music / George E. Lewis. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ), discography (p. ), and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-226-47695-7 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-226-47695-2 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians—History. 2. African American jazz musicians—Illinois—Chicago. 3. Avant-garde (Music) —United States— History—20th century. 4. Jazz—History and criticism. I. Title. ML3508.8.C5L48 2007 781.6506Ј077311—dc22 2007044600 o The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992. contents Preface: The AACM and American Experimentalism ix Acknowledgments xv Introduction: An AACM Book: Origins, Antecedents, Objectives, Methods xxiii Chapter Summaries xxxv 1 FOUNDATIONS AND PREHISTORY -

Wire No.234 Revised

THE WIRE WWW.THEWIRE.CO.UK ISSUE 234 AUGUST 2003 Robert Ashley Meet the electronic pioneer who took opera into the multimedia age. By Thom Holmes Built for Speed Textually hyperdense and accellerated for the televisual age, the multimedia music theatre of composer Robert Ashley has been called the future of opera, as well as the first to exploit the unique rhythms of the American voice. Following this year’s premiere of his new work Celestial Excursions, Thom Holmes meets the composer to discuss his founding role in the Sonic Arts Union, his love of TV, and his celebration of life on the margins. Photos: Chris Buck other for their living space. Today, the windows are open due to the warm weather. Ashley’s computers, keyboards and recording equipment are clustered in the centre of the space underneath a marquee-like canopy. The tent is there to protect the equipment from falling crumbs of concrete and ceiling plaster while the roof undergoes repairs. Despite the disruption, Ashley never loses his train of thought.’“That’s why so much popular music has to do with love,” he continues. “It puts a label on it and when it’s good, that label really works. It can’t do anything but that, no matter how hard people try. No matter how hard Bob Dylan tried or John Lennon tried, you can’t make popular music into anything except a labelling of your own experience that you never realised needed a label.” He sits up straight and places the palms of his hands firmly on the table in front of him. -

Press Release

MoMA EXHIBITION LOOKS AT MUSIC’S WIDE-RANGING INFLUENCE ON ARTISTS, ACROSS MEDIA, BEGINNING IN THE 1960s The Work of David Bowie, Laurie Anderson, Nam June Paik, and The Residents, Among Others, Brought Together in Looking at Music Looking at Music August 13, 2008—January 5, 2009 The Yoshiko and Akio Morita Gallery, second floor August 18—December 21, 2008 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters Press Preview: August 13, 2008, 9:30 a.m. to 10:30 a.m.; Screening at 10:30 a.m. NEW YORK, August 13, 2008—The Museum of Modern Art presents Looking at Music, an exhibition that explores music’s role in the interdisciplinary experimentation of the 1960s, when a dynamic cross-fertilization was taking place among music, video, installation, and what was known as “mixed media” art. In the decade between 1965 and 1975, an era of technological innovation fostered this radical experimentation, and artists responded with works that pushed boundaries across media. Comprising over 40 works from the Museum’s collection, the exhibition includes video, audio, books, lithographs, collage, and prints, by artists such as Laurie Anderson, Nam June Paik, Bruce Nauman, and John Cage. Their work in the exhibition is accompanied by related experimental magazines such as West Coast poet Wallace Berman’s Semina, along with drawings, prints, and photographs by John Cage, Jack Smith, and other radical thinkers. The exhibition, organized by Barbara London, Associate Curator, Department of Media, The Museum of Modern Art, is on view from August 13, 2008, to January 5, 2009; the accompanying film and video series in The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters, which includes 12 programs of nearly 50 works of documentary and experimental films along with music videos, will be on view August 18 to December 21, 2008. -

A Personal Reminiscence on the Roots of Computer Network Music

A Personal Reminiscence on the Roots of Computer Network Music S C o T G R e S h am -L ancast e R This historical reminiscence details the evolution of a type of electronic music.” I would add the impact of Sonic Arts Union and the music called “computer network music.” Early computer network music ONCE festival in Ann Arbor in the late 1960s, which neces- had a heterogeneous quality, with independent composers forming sarily includes the contributions of Gordon Mumma, Alvin a collective; over time, it has transitioned into the more autonomous ABSTRACT form of university-centered “laptop orchestra.” This transition points to Lucier, Robert Ashley, David Behrman and, of course, David a fundamental shift in the cultural contexts in which this artistic practice Tudor. was and is embedded: The early work derived from the post-hippie, When I browse the ubiquitous music applications (iTunes, neo-punk anarchism of cooperatives whose members dreamed that Spotify, etc.) that are tagging audio files and examine the machines would enable a kind of utopia. The latter is a direct outgrowth choices for “electronic music,” I am mystified. The history of the potential inherent in what networks actually are and of a sense of that I have experienced over the last four decades is not rep- social cohesion based on uniformity and standardization. The discovery that this style of computer music-making can be effectively used as a resented at all. Cage, Xenakis, Stockhausen, etc., and their curricular tool has also deeply affected the evolution and approaches fundamental electronic music contributions are nowhere to of many in the field.