Mentor and Disciples. Partners of the Heart Francisco S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medical Movies

Movies can provide you with a glimpse in to another world, explain a part of history and help you connect with patients. 28 Days (2000)- alcoholism and rehab 28 Days Later (2002) and 28 Weeks Later (2007)- escape of deadly virus A Beautiful Mind (2001)- a math genius suffers from schizophrenia A Mother’s Prayer (1995)- a mother plans for her son after she’s diagnosed with AIDS A Place for Annie (1994)- child with AIDS abandoned at birth A Private Matter (1992)- woman chooses to have an abortion after she finds out the fetus has severe problems Altered States (1980)- thriller about the research on altered states of consciousness Amnesia: The James Brighton Enigma (2005)- total loss of memory and its affects And The Band Played On (1993)- about the beginning of AIDS and the politics involved Article 99 (1992)- VA hospital with administration problems Awakenings (1990)- a new drug has coma patients waking up Boys on the Side (1995)- interactions regarding AIDS, homosexuality Bringing Out The Dead (1999)- burn out Britannia Hospital (1982)- psychiatric hospital that mirrors the downsides of Britain Carandiru (2003)- doctor initial arrives at a prison to study HIV but begins to see the people behind the infection Cider House Rules (1999)- a doctor of sorts deals with choosing to perform abortions or not City of Joy (1992)- working in the slums of Calcutta Clean and Sober (1988)- following a man who is dealing with cocaine addiction Coma (1978)- a doctor investigates why patients are showing up with brain damage after minor procedures Contagion (2011)- watch an epidemic unfold Dr. -

Books, Films, and Medical Humanities

Books, Films, and Medical Humanities Films 50/50, 2011 Amour, 2012 And the Band Played On, 1993 Awakenings, 1990 Away From Her, 2006 A Beautiful Mind, 2001 The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, 2007 In The Family, 2011 The Intouchables, 2011 Iris, 2001 My Left Foot, 1989 One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, 1975 Philadelphia, 1993 Rain Man, 1988 Silver Linings Playbook, 2012 The Station Agent, 2003 Temple Grandin, 2010 21 grams, 2003 Patch Adams, 1998 Wit, 2001 Gifted Hands: The Ben Carson Story, 2009 Awake, 2007 Something the Lord Made, 2004 Medicine Man, 1992 The Doctor, 1991 The Good Doctor, 2011 Side Effects, 2013 Books History/Biography Elmer, Peter and Ole Peter Grell, eds. Health, disease and society in Europe, 1500-1800: A Source Book. 2004. Foucault, Michel. The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception. 1963. 1 --Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason. 1964. Gilman, Ernest B. Plague Writing in Early Modern England. 2009. Harris, Jonathan Gil. Foreign Bodies and the Body Politic: Discourses of Social Pathology in Early Modern England. 1998. Healy, Margaret. Fictions of Disease in Early Modern England: Bodies, Plagues and Politics. 2001. Lindemann, Mary. Medicine and Society in Early Modern Europe. 1999. Markel, Howard. An Anatomy of Addiction: Sigmund Freud, William Halsted, and the Miracle Drug Cocaine. 2011. Morris, David B. The Culture of Pain. 1991. Moss, Stephanie and Kaara Peterson, eds. Disease, Diagnosis and Cure on the Early Modern Stage. 2004. Mukherjee, Siddhartha. The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer. 2010. Newman, Karen. -

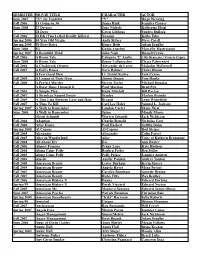

POPULAR DVD TITLES – As of JULY 2014

POPULAR DVD TITLES – as of JULY 2014 POPULAR TITLES PG-13 A.I. artificial intelligence (2v) (CC) PG-13 Abandon (CC) PG-13 Abduction (CC) PG Abe & Bruno PG Abel’s field (SDH) PG-13 About a boy (CC) R About last night (SDH) R About Schmidt (CC) R About time (SDH) R Abraham Lincoln: Vampire hunter (CC) (SDH) R Absolute deception (SDH) PG-13 Accepted (SDH) PG-13 The accidental husband (CC) PG-13 According to Greta (SDH) NRA Ace in the hole (2v) (SDH) PG Ace of hearts (CC) NRA Across the line PG-13 Across the universe (2v) (CC) R Act of valor (CC) (SDH) NRA Action classics: 50 movie pack DVD collection, Discs 1-4 (4v) NRA Action classics: 50 movie pack DVD collection, Discs 5-8 (4v) NRA Action classics: 50 movie pack DVD collection, Discs 9-12 (4v) PG-13 Adam (CC) PG-13 Adam Sandler’s eight crazy nights (CC) R Adaptation (CC) PG-13 The adjustment bureau (SDH) PG-13 Admission (SDH) PG Admissions (CC) R Adoration (CC) R Adore (CC) R Adrift in Manhattan R Adventureland (SDH) PG The adventures of Greyfriars Bobby NRA Adventures of Huckleberry Finn PG-13 The adventures of Robinson Crusoe PG The adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle (CC) PG The adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl in 3-D (SDH) PG The adventures of TinTin (CC) NRA An affair to remember (CC) NRA The African Queen NRA Against the current (SDH) PG-13 After Earth (SDH) NRA After the deluge R After the rain (CC) R After the storm (CC) PG-13 After the sunset (CC) PG-13 Against the ropes (CC) NRA Agatha Christie’s Poirot: The definitive collection (12v) PG The age of innocence (CC) PG Agent -

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Sum 2007 "V

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Sum 2007 "V" for Vendetta "V" Hugo Weaving Fall 2006 13 Going on 30 Jenna Rink Jennifer Garner Sum 2008 27 Dresses Jane Nichols Katherine Heigl ? 28 Days Gwen Gibbons Sandra Bullock Fall 2006 2LDK (Two Lethal Deadly Killers) Nozomi Koike Eiko Spring 2006 40 Year Old Virgin Andy Stitzer Steve Carell Spring 2005 50 First Dates Henry Roth Adam Sandler Sum 2008 8½ Guido Anselmi Marcello Mastroianni Spring 2007 A Beautiful Mind John Nash Russell Crowe Fall 2006 A Bronx Tale Calogero 'C' Anello Lillo Brancato / Francis Capra Sum 2008 A Bronx Tale Sonny LoSpeecchio Chazz Palmenteri Fall 2006 A Clockwork Orange Alexander de Large Malcolm McDowell Fall 2007 A Doll's House Nora Helmer Claire Bloom ? A Few Good Men Lt. Daniel Kaffee Tom Cruise Fall 2005 A League of Their Own Jimmy Dugan Tom Hanks Fall 2000 A Perfect Murder Steven Taylor Michael Douglas ? A River Runs Through It Paul Maclean Brad Pitt Fall 2005 A Simple Plan Hank Mitchell Bill Paxton Fall 2007 A Streetcar Named Desire Stanley Marlon Brando Fall 2005 A Thin Line Between Love and Hate Brandi Lynn Whitefield Fall 2007 A Time To Kill Carl Lee Haley Samuel L. Jackson Spring 2007 A Walk to Remember Landon Carter Shane West Sum 2008 A Walk to Remember Jaime Mandy Moore ? About Schmidt Warren Schmidt Jack Nickleson Fall 2004 Adaption Charlie/Donald Nicholas Cage Fall 2000 After Hours Paul Hackett Griffin Dunn Spring 2005 Al Capone Al Capone Rod Steiger Fall 2005 Alexander Alexander Colin Farrel Fall 2005 Alice in Wonderland Alice Voice of Kathryn Beaumont -

Table of Contents

Vol. 11, Issue 2 Dr. Jeanne Ramirez Mather, Ed. March 2009 When Politics and The The History Behind Oklahoma’s Black Towns Olympics Collide While supposedly the The development of Black former slaves began receiving land took part in the Oklahoma Land Olympics are apolitical, in towns in America took place allotments from the tribes. In ad- Run to secure property and reality politics have been predominantly between 1865 dition, many freed slaves fled from make a homestead. One exam- woven throughout Olympic and 1920. What constitutes an the Deep South to Oklahoma to ple of this was Edwin P. history in a variety of ways. “all-Black town?” One that escape the rigid Jim Crow Laws. McCabe, a former state auditor The first recorded Olympic has at least two of the follow- That is not to say that of Kansas, a land developer and Games are generally accepted ing criteria: Black founder(s); Oklahomans were particularly speculator, an attorney, a news- to have occurred in 776 B.C.E. governance led by Black offi- open-minded, but they had not paper owner, politician, and The Olympics, 776 B.C.E. to cials; predominantly Black legislated formal Jim Crow Laws Oklahoma immigration pro- 393 A.D., were celebrated as a population and/or a Black at this time perhaps in part because moter. He was instrumental in religious festival, until Roman postmaster. During the afore- Oklahoma was not yet a state. As founding the town of Langston Emperor Theodosius banned mentioned time, about fifty a result ,African Americans in and providing the initial land them for being a “pagan” festi- identifiable Black towns and/or upon which Langston Univer- val. -

Emmy Award Winners

CATEGORY 2035 2034 2033 2032 Outstanding Drama Title Title Title Title Lead Actor Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Lead Actress—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actor—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actress—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Outstanding Comedy Title Title Title Title Lead Actor—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Lead Actress—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actor—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actress—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Outstanding Limited Series Title Title Title Title Outstanding TV Movie Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Lead Actor—L.Ser./Movie Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Lead Actress—L.Ser./Movie Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actor—L.Ser./Movie Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actress—L.Ser./Movie Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title CATEGORY 2031 2030 2029 2028 Outstanding Drama Title Title Title Title Lead Actor—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Lead Actress—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actor—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actress—Drama Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Outstanding Comedy Title Title Title Title Lead Actor—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Lead Actress—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. Actor—Comedy Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Name, Title Supp. -

MAN of LA MANCHA Book by Dale Wasserman Music by Mitch Leigh Lyrics by Joe Darion Original Production Staged by Albert Marre Originally Produced by Albert W

barringtonstagecompany AWARD-WINNING THEATRE IN DOWNTOWN PITTSFIELD Julianne Boyd, Artistic Director Tristan Wilson, Managing Director and Cynthia and Randolph Nelson present MAN OF LA MANCHA Book by Dale Wasserman Music by Mitch Leigh Lyrics by Joe Darion Original Production Staged by Albert Marre Originally Produced by Albert W. Selden and Hal James Starring Jeff McCarthy and Felicia Boswell Rosalie Burke Meg Bussert Ed Dixon Todd Horman Lexi Janz Sara Kase Matthew Krob Parker Krug Sean MacLaughlin Louie Napoleon Waldemar Quinones-Villanueva Chris Ramirez Lyonel Reneau Tom Alan Robbins Ben Schrager Jonathan Spivey Joseph Torello Scenic Designer Costume Designer Lighting Designer Sound Designer James Kronzer Olivera Gajic Chris Lee Ed Chapman Director of Production Casting Press Representative Jeff Roudabush Pat McCorkle, CSA Charlie Siedenburg Fight Choreographer Production Stage Manager Ryan Winkles Renee Lutz Musical Direction by Darren R. Cohen Choreography by Greg Graham Directed by Julianne Boyd Man of La Mancha is sponsored in part by Bonnie and Terry Burman & The Feigenbaum Foundation MAN OF LA MANCHA is presented by arrangement with Tams-Witmark Music Library, Inc., 560 Lexington Avenue, New York, NY 10022. BOYD-QUINSON MAINSTAGE JUNE 10-JULY 11, 2015 Cast (in order of appearance) Esté Fuego Dancer/Moorish Dancer ............................................................... Lexi Janz Esté Fuego Singer/Muleteer .................................................................. Joseph Torello* Cervantes/Don Quixote ........................................................................... -

The Colored Pill: a History Film Performance Exposing Race Based Medicines

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 2020 The Colored Pill: A History Film Performance Exposing Race Based Medicines Wanda Lakota Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons The Colored Pill: A History Film Performance Exposing Race Based Medicines __________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the College of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________ by Wanda Lakota June 2020 Advisor: Dr. Bernadette Marie Calafell ©Copyright by Wanda Lakota 2020 All Rights Reserved Author: Wanda Lakota Title: The Colored Pill: A History Film Performance Exposing Race Based Medicines Advisor: Dr. Bernadette Marie Calafell Degree Date: June 2020 ABSTRACT Of the 32 pharmaceuticals approved by the FDA in 2005, one medicine stood out. That medicine, BiDil®, was a heart failure medication that set a precedent for being the first approved race based drug for African Americans. Though BiDil®, was the first race specific medicine, racialized bodies have been used all throughout history to advance medical knowledge. The framework for race, history, and racialized drugs was so multi- tiered; it could not be conceptualized from a single perspective. For this reason, this study examines racialized medicine through performance, history, and discourse analysis. The focus of this work aimed to inform and build on a new foundation for social inquiry—using a history film performance to elevate knowledge about race based medicines. -

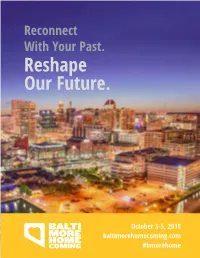

Reshape Our Future

Header here Reconnect With Your Past. Reshape Our Future. October 3-5, 2018 baltimorehomecoming.com #bmorehome#baltimorehome 1 Header here PHOTO BY ISAAC GUERRERO @S_ISAAC_GUERRERO #baltimorehome 2 #baltimorehome 3 WELCOME DEAR FRIENDS, Welcome home! We are so excited to have you back in Charm City for the first annual Baltimore Homecoming. We are grateful to the hundreds of leaders from across Baltimore – reverends and educators, artists and business executives, activists and philanthropists – who joined together to organize this event. We each have our own memories of Baltimore – a humid summer afternoon or spring ballgame, a favorite teacher or a first job. We hope that you take time while you’re home to reconnect with your past and savor the city – catch up with friends and family, drop by a favorite restaurant, or visit an old neighborhood. Reconnecting is the first step. But our deeper hope is that you begin to forge a new relationship to the city. Whether you left five years ago or fifty, Baltimore has evolved. The Baltimore of today has a dynamic real estate market and budding technology sector. Our artists are leading the national conversation on race and politics. Our nonprofit entrepreneurs are on the cutting-edge of social change. The Port of Baltimore is one of the fastest growing in the U.S. The city’s growth has emerged from and complemented our historic pillars of strength – a rich cultural heritage, world-class research institutions, strategic geographic location, and beautiful waterfront. Baltimore faces significant challenges that we cannot ignore: segregation, entrenched poverty, crime and violence. -

Seneca Village History Exhibit Black History Month Film Festival

Bronx Community College Weekly Newsletter Monday, February 8, 2016 Seneca Village History Exhibit College Discovery CD Scholars Now through Friday, February 26 Workshop Seneca Village was a self-determined 19th century free Black Thursday, February 11, 12 - 2 p.m., in Meister Hall [ME], community in what we know today as Central Park. Discover Schwendler Auditorium this historic hamlet’s pursuit of independence, social justice, and the right to call New York City “home.” This exhibit, courtesy Millions of Americans are affected of the Institute for the Exploration of Seneca Village History, by mental health conditions every can be viewed in the following campus locations: Colston Hall year. In addition to the person directly [CO], Lobby, 5th Floor and History Department, 3rd Floor; North experiencing a mental illness, family, Hall and Library [NL], 2nd Floor; Meister Hall [ME], Learning friends and communities are also Commons, Sub-Basement (SB) and Roscoe Brown Student affected. Join us as we welcome author Hakeem Rahim, a leading Center [BC], 1st Floor. African American voice in mental illness, wellness and recovery. Mr. In honor of Black History Month, you are invited to events Rahim speaks openly about his 15 year journey with bipolar disorder planned around the historical narrative and themes of Seneca to audiences across the country. Inspired to address the stigma of Village (watch for announcements). mental health, he became a certified National Alliance of Mental Illness (NAMI) speaker. Lunch will be provided and there will be a Black History Month Film Festival: book signing session at the end of the workshop. Sponsored by the College Discovery Program and the Office of Health Services. -

AEMB National Newsletter Alpha Eta Mu Beta National Biomedical Engineering Honor Society

April 2005 Volume 3, Issue 2 AEMB National Newsletter Alpha Eta Mu Beta National Biomedical Engineering Honor Society 2004-2006 National Officers • Attention Officers National President With the year nearly to a close, we hope that chapters Herbert Voigt, Ph.D. have had a fun and productive year. As you are looking Boston University to elect new officers for next year please note that at [email protected] least the Chapter President needs to attend the AEMB Annual Business Meeting. The meeting will be held at National Student President the BMES Fall Meeting in Baltimore, September 28th to Heather Swanson October 1st, 2005. Milwaukee School of Since we know that the seniors are going to be busy Engineering with jobs or grad school next year, just a reminder to, [email protected] after you have elected new officers, let us know who your new officers are so we can communicate with your National Student Vice President chapter. The forms are available on the AEMB website Teresa Murray http://ahmb.org using the “Chapter Status Form" and Arizona State University mail to: AEMB c/o BMES, 8401 Corporate Dr., Suite 225, Landover, MD, 20785-2224, (301)459-1999, [email protected] (301)459-2444(fax), or email the information to [email protected]. National Student Treasurer Vivek Mukhatyar Also DUES ARE DUE! If your chapter has not Boston University already done so, please send in the initiates form with [email protected] their national dues. If you need a form, you can access it at our web site http://ahmb.org; click on the ‘Forms’ link or call 301-459-1999. -

The Seventh and Final Chapter of the Harry Potter Story Begins As Harry

“Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 2,” is the final adventure in the Harry Potter film series. The much-anticipated motion picture event is the second of two full-length parts. In the epic finale, the battle between the good and evil forces of the wizarding world escalates into an all-out war. The stakes have never been higher and no one is safe. But it is Harry Potter who may be called upon to make the ultimate sacrifice as he draws closer to the climactic showdown with Lord Voldemort. It all ends here. “Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 2” stars Daniel Radcliffe, Rupert Grint and Emma Watson, reprising their roles as Harry Potter, Ron Weasley and Hermione Granger. The film’s ensemble cast also includes Helena Bonham Carter, Robbie Coltrane, Warwick Davis, Tom Felton, Ralph Fiennes, Michael Gambon, Ciarán Hinds, John Hurt, Jason Isaacs, Matthew Lewis, Gary Oldman, Alan Rickman, Maggie Smith, David Thewlis, Julie Walters and Bonnie Wright. The film was directed by David Yates, who also helmed the blockbusters “Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix,” “Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince” and “Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 1.” David Heyman, the producer of all of the Harry Potter films, produced the final film, together with David Barron and J.K. 1 Rowling. Screenwriter Steve Kloves adapted the screenplay, based on the book by J.K. Rowling. Lionel Wigram is the executive producer. Behind the scenes, the creative team included director of photography Eduardo Serra, production designer Stuart Craig, editor Mark Day, visual effects supervisor Tim Burke, special effects supervisor John Richardson, and costume designer Jany Temime.