Western Manhood in Clint Eastwood's Unforgiven 2/1/11 9:24 AM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pennsylvania State University

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts REVENGE AND STORYTELLING IN ENGLISH DRAMA, 1580-1640 A Dissertation in English by Heather Janine Murray © 2008 Heather Janine Murray Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2008 ii The dissertation of Heather Janine Murray was reviewed and approved* by the following: Linda Woodbridge Josephine Berry Weiss Chair in the Humanities and Professor of English Thesis Advisor Chair of Committee Laura Knoppers Professor of English Garrett Sullivan Professor of English Marcy North Associate Professor of English Christine Clark-Evans Associate Professor of French, Women's Studies, and African and African American Studies Robert R. Edwards Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of English and Comparative Literature Director of Graduate Studies Department of English *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. iii ABSTRACT This dissertation proposes that storytelling functions as a catalyst for revenge in early modern English revenge tragedy. Chapters on Kyd’s The Spanish Tragedy, Shakespeare’s first tetralogy, Cary’s The Tragedy of Mariam, and Ford’s ‘Tis Pity She’s a Whore examine the ways in which storytelling perpetuates acts of vengeance by individuals, families, and nations. Two premises shape the central argument. First, revengers come from within an intimate circle of family and friends; second, the desire for revenge is maintained, and the act of revenge later justified, through story-telling within this circle. Crimes ostensibly committed against an individual affect those nearest to the injured party, particularly close friends and family. Consequently, the revenger almost always comes from one of these two groups. -

Collision Course

FINAL-1 Sat, Jul 7, 2018 6:10:55 PM Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment for the week of July 14 - 20, 2018 HARTNETT’S ALL SOFT CLOTH CAR WASH Collision $ 00 OFF 3ANY course CAR WASH! EXPIRES 7/31/18 BUMPER SPECIALISTSHartnett's Car Wash H1artnett x 5` Auto Body, Inc. COLLISION REPAIR SPECIALISTS & APPRAISERS MA R.S. #2313 R. ALAN HARTNETT LIC. #2037 DANA F. HARTNETT LIC. #9482 Ian Anthony Dale stars in 15 WATER STREET “Salvation” DANVERS (Exit 23, Rte. 128) TEL. (978) 774-2474 FAX (978) 750-4663 Open 7 Days Mon.-Fri. 8-7, Sat. 8-6, Sun. 8-4 ** Gift Certificates Available ** Choosing the right OLD FASHIONED SERVICE Attorney is no accident FREE REGISTRY SERVICE Free Consultation PERSONAL INJURYCLAIMS • Automobile Accident Victims • Work Accidents • Slip &Fall • Motorcycle &Pedestrian Accidents John Doyle Forlizzi• Wrongfu Lawl Death Office INSURANCEDoyle Insurance AGENCY • Dog Attacks • Injuries2 x to 3 Children Voted #1 1 x 3 With 35 years experience on the North Insurance Shore we have aproven record of recovery Agency No Fee Unless Successful While Grace (Jennifer Finnigan, “Tyrant”) and Harris (Ian Anthony Dale, “Hawaii Five- The LawOffice of 0”) work to maintain civility in the hangar, Liam (Charlie Row, “Red Band Society”) and STEPHEN M. FORLIZZI Darius (Santiago Cabrera, “Big Little Lies”) continue to fight both RE/SYST and the im- Auto • Homeowners pending galactic threat. Loyalties will be challenged as humanity sits on the brink of Business • Life Insurance 978.739.4898 Earth’s potential extinction. Learn if order can continue to suppress chaos when a new Harthorne Office Park •Suite 106 www.ForlizziLaw.com 978-777-6344 491 Maple Street, Danvers, MA 01923 [email protected] episode of “Salvation” airs Monday, July 16, on CBS. -

Young Adult Audiences' Perceptions of Mediated

Mediated Sexuality and Teen Pregnancy: Exploring The Secret Life Of The American Teenager A thesis submitted to the College of Communication and Information of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Nicole D. Reamer August, 2012 Thesis written by Nicole D. Reamer B.A., The University of Toledo, 2007 M.A., Kent State University, 2012 Approved by Jeffrey T. Child, Ph.D., Advisor Paul Haridakis, Ph.D., Director, School of Communication Studies Stanley T. Wearden, Ph.D., Dean, College of Communication and Information Table of Contents Page TABLE OF CONTENTS iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS v CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION 1 TV and Socialization of Attitudes, Values, and Beliefs Among Young Adults 1 The Secret Life of the American Teenager 3 Teens, Sex, and the Media 4 II. REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE 7 Social Cognitive Theory 7 Research from a Social Cognitive Framework 11 Program-specific studies 11 Sexually-themed studies 13 Cultivation Theory 14 Research from a Cultivation perspective 16 The Adolescent Audience and Media Research 17 Sexuality in the Media 19 Alternative Media 20 Film and Television 21 Focus of this Study 27 III. METHODOLOGY 35 Sample Selection 35 Coding Procedures 36 Coder Training 37 Coding Process 39 Sexually Oriented Content 39 Overall Scene Content 40 Target 41 Location 42 Topic or Activity 43 Valence 44 Demographics 45 Analysis 46 IV. RESULTS 47 Sexually Oriented Content 47 Overall Scene Content 48 Target 48 iii Location 50 Topic or Activity 51 Valence 52 Topic Valence Variation by Target 54 V. DISCUSSION 56 Summary of Findings and Implications 58 Target and Location 59 Topic and Activity 63 Valence 65 Study Limitations 67 Future Directions 68 Audience Involvement 69 Conclusion 71 APPENDICES A. -

Sample Download

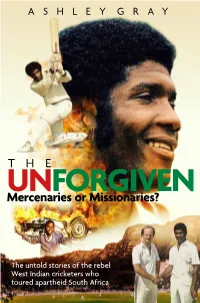

ASHLEY GRAY THE UN FORGIVEN THE MercenariesUNFORGIVEN or Missionaries? The untold stories of the rebel West Indian cricketers who toured apartheid South Africa Contents Introduction. 9. Lawrence Rowe . 26. Herbert Chang . 56. Alvin Kallicharran . 71 Faoud Bacchus . 88 Richard Austin . .102 . Alvin Greenidge . 125 Emmerson Trotman . 132 David Murray . .137 . Collis King . 157. Sylvester Clarke . .172 . Derick Parry . 189 Hartley Alleyne . .205 . Bernard Julien . .220 . Albert Padmore . .238 . Monte Lynch . 253. Ray Wynter . 268. Everton Mattis . .285 . Colin Croft . 301. Ezra Moseley . 309. Franklyn Stephenson . 318. Acknowledgements . 336 Scorecards. .337 . Map: Rebel Origins. 349. Selected Bibliography . 350. Lawrence Rowe ‘He was a hero here’ IT’S EASY to feel anonymous in the Fort Lauderdale sprawl. Shopping malls, car yards and hotels dominate the eyeline for miles. The vast concrete expanses have the effect of dissipating the city’s intensity, of stripping out emotion. The Gallery One Hilton Fort Lauderdale is a four-star monolith minutes from the Atlantic Ocean. Lawrence Rowe, a five-star batsman in his prime, is seated in the hotel lounge area. He has been trading off the anonymity of southern Florida for the past 35 years, an exile from Kingston, Jamaica, the highly charged city that could no longer tolerate its stylish, contrary hero. Florida is a haven for Jamaican expats; it’s a short 105-minute flight across the Caribbean Sea. Some of them work at the hotel. Bartender Alyssa, a 20-something from downtown Kingston, is too young to know that the neatly groomed septuagenarian she’s serving a glass of Coke was once her country’s most storied sportsman. -

Professional Wrestling, Sports Entertainment and the Liminal Experience in American Culture

PROFESSIONAL WRESTLING, SPORTS ENTERTAINMENT AND THE LIMINAL EXPERIENCE IN AMERICAN CULTURE By AARON D, FEIGENBAUM A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2000 Copyright 2000 by Aaron D. Feigenbaum ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There are many people who have helped me along the way, and I would like to express my appreciation to all of them. I would like to begin by thanking the members of my committee - Dr. Heather Gibson, Dr. Amitava Kumar, Dr. Norman Market, and Dr. Anthony Oliver-Smith - for all their help. I especially would like to thank my Chair, Dr. John Moore, for encouraging me to pursue my chosen field of study, guiding me in the right direction, and providing invaluable advice and encouragement. Others at the University of Florida who helped me in a variety of ways include Heather Hall, Jocelyn Shell, Jim Kunetz, and Farshid Safi. I would also like to thank Dr. Winnie Cooke and all my friends from the Teaching Center and Athletic Association for putting up with me the past few years. From the World Wrestling Federation, I would like to thank Vince McMahon, Jr., and Jim Byrne for taking the time to answer my questions and allowing me access to the World Wrestling Federation. A very special thanks goes out to Laura Bryson who provided so much help in many ways. I would like to thank Ed Garea and Paul MacArthur for answering my questions on both the history of professional wrestling and the current sports entertainment product. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

October 2011

OctOber 2011 7:00 PM ET/4:00 PM PT 3:15 PM ET/12:15 PM PT 1:00 PM ET/10:00 AM PT 6:00 PM CT/5:00 PM MT 2:15 PM CT/1:15 PM MT 12:00 PM CT/11:00 AM MT The Wild Bunch - In Retro/Na- Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves Spaceballs tional Film Registry 5:45 PM ET/2:45 PM PT 2:45 PM ET/11:45 AM PT SATURDAY, OCTOBER 1 9:30 PM ET/6:30 PM PT 4:45 PM CT/3:45 PM MT 1:45 PM CT/12:45 PM MT 12:00 AM ET/9:00 PM PT 8:30 PM CT/7:30 PM MT Unforgiven - National Film Regis- Gremlins - Spotlight Feature 11:00 PM CT/10:00 PM MT Unforgiven - National Film Regis- try/Spotlight Feature 4:35 PM ET/1:35 PM PT The Country Bears - KIDS try/Spotlight Feature 8:00 PM ET/5:00 PM PT 3:35 PM CT/2:35 PM MT FIRST!/kidScene “Friday Nights” 11:45 PM ET/8:45 PM PT 7:00 PM CT/6:00 PM MT Gremlins 2: The New Batch 1:30 AM ET/10:30 PM PT 10:45 PM CT/9:45 PM MT A Face in the Crowd - In Retro/Na- 6:30 PM ET/3:30 PM PT 12:30 AM CT/11:30 PM MT The Wild Bunch - In Retro/Na- tional Film Registry 5:30 PM CT/4:30 PM MT White Squall tional Film Registry 10:15 PM ET/7:15 PM PT The Lost Boys 3:45 AM ET/12:45 AM PT 9:15 PM CT/8:15 PM MT 8:15 PM ET/5:15 PM PT 2:45 AM CT/1:45 AM MT SUNDAY, OCTOBER 2 Papillon - In Retro 7:15 PM CT/6:15 PM MT Everybody’s All American 2:15 AM ET/11:15 PM PT Beetlejuice 6:00 AM ET/3:00 AM PT 1:15 AM CT/12:15 AM MT MONDAY, OCTOBER 3 10:00 PM ET/7:00 PM PT 5:00 AM CT/4:00 AM MT Unforgiven - National Film Regis- 1:00 AM ET/10:00 PM PT 9:00 PM CT/8:00 PM MT Zula Patrol: Animal Adventures in try/Spotlight Feature 12:00 AM CT/11:00 PM MT Big Fish Space 4:30 AM ET/1:30 AM PT -

Modernizing the Greek Tragedy: Clint Eastwood’S Impact on the Western

Modernizing the Greek Tragedy: Clint Eastwood’s Impact on the Western Jacob A. Williams A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies University of Washington 2012 Committee: Claudia Gorbman E. Joseph Sharkey Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences Table of Contents Dedication ii Acknowledgements iii Introduction 1 Section I The Anti-Hero: Newborn or Reborn Hero? 4 Section II A Greek Tradition: Violence as Catharsis 11 Section III The Theseus Theory 21 Section IV A Modern Greek Tale: The Outlaw Josey Wales 31 Section V The Euripides Effect: Bringing the Audience on Stage 40 Section VI The Importance of the Western Myth 47 Section VII Conclusion: The Immortality of the Western 49 Bibliography 53 Sources Cited 62 i Dedication To my wife and children, whom I cherish every day: To Brandy, for always being the one person I can always count on, and for supporting me through this entire process. You are my love and my life. I couldn’t have done any of this without you. To Andrew, for always being so responsible, being an awesome big brother to your siblings, and always helping me whenever I need you. You are a good son, and I am proud of the man you are becoming. To Tristan, for always being my best friend, and my son. You never cease to amaze and inspire me. Your creativity exceeds my own. To Gracie, for being my happy “Pretty Princess.” Thank you for allowing me to see the world through the eyes of a nature-loving little girl. -

Films Shown by Series

Films Shown by Series: Fall 1999 - Winter 2006 Winter 2006 Cine Brazil 2000s The Man Who Copied Children’s Classics Matinees City of God Mary Poppins Olga Babe Bus 174 The Great Muppet Caper Possible Loves The Lady and the Tramp Carandiru Wallace and Gromit in The Curse of the God is Brazilian Were-Rabbit Madam Satan Hans Staden The Overlooked Ford Central Station Up the River The Whole Town’s Talking Fosse Pilgrimage Kiss Me Kate Judge Priest / The Sun Shines Bright The A!airs of Dobie Gillis The Fugitive White Christmas Wagon Master My Sister Eileen The Wings of Eagles The Pajama Game Cheyenne Autumn How to Succeed in Business Without Really Seven Women Trying Sweet Charity Labor, Globalization, and the New Econ- Cabaret omy: Recent Films The Little Prince Bread and Roses All That Jazz The Corporation Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room Shaolin Chop Sockey!! Human Resources Enter the Dragon Life and Debt Shaolin Temple The Take Blazing Temple Blind Shaft The 36th Chamber of Shaolin The Devil’s Miner / The Yes Men Shao Lin Tzu Darwin’s Nightmare Martial Arts of Shaolin Iron Monkey Erich von Stroheim Fong Sai Yuk The Unbeliever Shaolin Soccer Blind Husbands Shaolin vs. Evil Dead Foolish Wives Merry-Go-Round Fall 2005 Greed The Merry Widow From the Trenches: The Everyday Soldier The Wedding March All Quiet on the Western Front The Great Gabbo Fires on the Plain (Nobi) Queen Kelly The Big Red One: The Reconstruction Five Graves to Cairo Das Boot Taegukgi Hwinalrmyeo: The Brotherhood of War Platoon Jean-Luc Godard (JLG): The Early Films, -

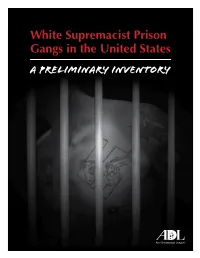

White Supremacist Prison Gangs in the United States a Preliminary Inventory Introduction

White Supremacist Prison Gangs in the United States A Preliminary Inventory Introduction With rising numbers and an increasing geographical spread, for some years white supremacist prison gangs have constitut- ed the fastest-growing segment of the white supremacist movement in the United States. While some other segments, such as neo-Nazis and the Ku Klux Klan, have suffered stagnation or even decline, white supremacist prison gangs have steadily been growing in numbers and reach, accompanied by a related rise in crime and violence. What is more, though they are called “prison gangs,” gangs like the Aryan Brotherhood of Texas, Aryan Circle, European Kindred and others, are just as active on the streets of America as they are behind bars. They plague not simply other inmates, but also local communities across the United States, from California to New Hampshire, Washington to Florida. For example, between 2000 and 2015, one single white supremacist prison gang, the Aryan Brotherhood of Texas, was responsible for at least 33 murders in communities across Texas. Behind these killings were a variety of motivations, including traditional criminal motives, gang-related murders, internal killings of suspected informants or rules-breakers, and hate-related motives directed against minorities. These murders didn’t take place behind bars—they occurred in the streets, homes and businesses of cities and towns across the Lone Star State. When people hear the term “prison gang,” they often assume that such gang members plague only other prisoners, or perhaps also corrections personnel. They certainly do represent a threat to inmates, many of whom have fallen prey to their violent attacks. -

Pro Wrestling Over -Sell

TTHHEE PPRROO WWRREESSTTLLIINNGG OOVVEERR--SSEELLLL™ a newsletter for those who want more Issue #1 Monthly Pro Wrestling Editorials & Analysis April 2011 For the 27th time... An in-depth look at WrestleMania XXVII Monthly Top of the card Underscore It's that time of year when we anything is responsible for getting Eddie Edwards captures ROH World begin to talk about the forthcoming WrestleMania past one million buys, WrestleMania, an event that is never it's going to be a combination of Tile in a shocker─ the story that makes the short of talking points. We speculate things. Maybe it'll be the appearances title change significant where it will rank on a long, storied list of stars from the Attitude Era of of highs and lows. We wonder what will wrestling mixed in with the newly Shocking, unexpected surprises seem happen on the show itself and gossip established stars that generate the to come few and far between, especially in the about our own ideas and theories. The need to see the pay-per-view. Perhaps year 2011. One of those moments happened on road to WreslteMania 27 has been a that selling point is the man that lit March 19 in the Manhattan Center of New York bumpy one filled with both anticipation the WrestleMania fire, The Rock. City. Eddie Edwards became the fifteenth Ring and discontent, elements that make the ─ So what match should go on of Honor World Champion after defeating April 3 spectacular in Atlanta one of the last? Oddly enough, that's a question Roderick Strong in what was described as an more newsworthy stories of the year. -

Black Cowboys: Ned Logan and the Portrayal of Blackness in Unforgiven

Black Cowboys: Ned Logan and the Portrayal of Blackness in Unforgiven The Oscars, film critics, and viewers alike have witnessed and praised the plot and performance of Unforgiven for many reasons. Will Munny still stands as the first image that comes to mind when thinking about Unforgiven - either his concerned face, him riding his horse, falling into mud, or infamously killing the town sheriff, Little Bill. Will Munny stands as the face of Unforgiven, similar to how Clint Eastwood stands as the mind behind the film. However, after further watching, re-watching, and engaging in a close viewing of the film, especially as a Black viewer, Ned Logan becomes the most important and different character in the film to me. Analysis into the film (while having my personal Black experience as context) reveals both a dichotomy and a purpose that Ned, and only Ned, has as the only Black figure in the film. I believe these distinct characterizations of Ned relate to his Blackness and the lack of diversity on and off screen. With the context of film history, Black cowboys in the nineteenth century, and through my eyes as a Black film viewer, I center Ned and try to understand how his character speaks to issues in film-making as it pertains to Black stories. Ned’s dynamic in this film interests me because he becomes both hyper-visible and invisible as a character. Almost everything he does and says centers Will, making him a classic sidekick. At the same time, Ned’s guidance to Will, and even his death, single-handedly shape Will’s decisions and character development in the movie.