Mousaion 27(2) 2009 Special Issue Layout.Indd 2 3/17/2010 2:11:06 PM a Number Paints a Thousand Words

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lee-Roman-Dutch-Law.Pdf

I ,- AN INTRODUCTION TO ROMAN-DUTCH LAW R! W.^'LEE, B.C.L., M.A. DEAN OF THE LAW FACULTY, M CGILL UNIVERSITY, MONTREAL ADVOCATE OF THE SUPREME COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA OF GRAY'S INN, BARRISTER-AT-LAW AND LATELY PROFESSOR OF ROMAN-DUTCH LAW IN THE UNIVERSITY OF LONDON OXFORD AT THE CLARENDON PRESS OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON EDINBURGH GLASGOW NEW YORK TORONTO MELBOURNE BOMBAY HUMPHREY MILFORD M.A. PUBLISHER TO THE UNIVERSITY PRINTED IN ENGLAND AT THE OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS TO THE HON. J. G. KOTZE ONE OF HIS MAJESTY'S JUDGES OF THE SUPREME COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA LATE CHIEF JUSTICE OF THE TRANSVAAL a 2 PREFACE THIS book, as its title indicates, is an Introduction to Roman-Dutch Law. It has grown out of a course of lectures delivered in the University of London at intervals in the years 1906-14. During this time I was frequently asked by students to recommend a text-book which would help them in their reading and perhaps enable them to satisfy the requirements of the University or of the Council of Legal Education. The book was not to be found. The classical Introduction to the Jurisprudence of the Province of Holland of Grotius, published in the year 1631, inevitably leaves the reader in a state of bewilderment as to the nature and content of the Roman- Dutch Law administered at the present day by the Courts of South Africa, Ceylon, and British Guiana. The same must be said of the treatise of Simon van Leeuwen entitled The Roman-Dutch Law, published in 1664, and of the elementary Handbook of Joannes van der Linden, published in 1806. -

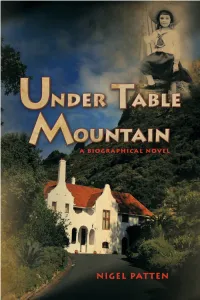

UNDER TABLE MOUNTAIN a Biographical Novel

UNDER TABLE MOUNTAIN a biographical novel by NIGEL PATTEN Copyright © 2011 All rights reserved—Nigel Patten No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or by any information storage retrieval system, without the permission, in writing, from the publisher. Strategic Book Group P.O. Box 333 Durham CT 06422 www.StrategicBookClub.com Design: Dedicated Business Solutions, Inc. (www.netdbs.com) ISBN 978-1-61897-161-6 The last decade of the 19th century were troubled years in South Africa. Tension between Britain and the two Boer republics, the Transvaal and the Orange Free State, increased until war became inevitable. These turbulent ten years saw many notable fi gures pass through Cape Town at various times and for various reasons, fi gures like Robert Baden-Powell, Rudyard Kipling, Jan Smuts or Cecil Rhodes. All of them were friends, guests or visitors at ‘Mon Desir’, the home of Sir Henry Juta, barrister and Speaker of the Cape House. This is the story of Louise Juta, the youngest of his four daughters, from her birth until she left South Africa in 1904 to go to school in England and never return. She spent the last years of her long life in Switzerland. I would drop in most days for an hour or two to play scrabble with Lady Luia Forbes, as she then was, and listen to her reminiscing. This is the result. Sir Henry Juta Lady Luia Forbes Louise Juta For Luia in fond memory of the many hours we spent together. -

Towards a Legal History of White Women in the Transvaal, 1877-1899

TOWARDS A LEGAL HISTORY OF WHITE WOMEN IN THE TRANSVAAL, 1877-1899 by MARELIZE GROBLER Submitted as requirement for the degree MAGISTER HEREDITATIS CULTURAEQUE SCIENTIAE (HISTORY) in the Department of Historical and Heritage Studies Faculty of Humanities University of Pretoria Pretoria 2009 Supervisor: Prof. L. Kriel Co-supervisor: Prof. K. Harris © University of Pretoria I. PREFACE If one considers South African history as a whole, white women in the Transvaal as a group have been somewhat neglected by historians.1 This study is a first step in rectifying this neglect, by using legal sources in a historical context to create a space for the women, one on which future research can build. This space is referred to as a stage, and the theoretical thinking behind the use of the stage analogy is discussed in chapter 2.2 What it translates to in practice is that women played out their lives on a historical stage. The stage is constructed by various means: legal sources are used to build it, a study of ‘life’ in the Transvaal is the backdrop, and court cases are the mise-en-scène. This is a study of white, not black, women, and the determining factor is scope. Black women were not perceived as equal citizens by the Transvaal’s leaders or its white inhabitants, but most importantly, they had their own legal system.3 Eventually, one would like to reach a stage where black and white women’s rights could be studied simultaneously, but that as yet is not possible. The rights of neither of the two female populations have been sufficiently explored; this study aims to redress the situation as far as the whites were concerned. -

BETTY FREUND: a NURSE in FRANCE - Part II Compiled and Edited by Betty Hugo*

Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol 15, Nr 2, 1985. http://scientiamilitaria.journals.ac.za BETTY FREUND: A NURSE IN FRANCE - Part II Compiled and edited by Betty Hugo* Accounts of Betty's death and funeral service, newspaper cuttings, and a copy of the pro- gramme issued at a Memorial Service held in Cape Town in 1925. Betty Freund's grave (in the Protestant Section of the Cannes Cemetery) 1 Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol 15, Nr 2, 1985. http://scientiamilitaria.journals.ac.za THE CABLE THE REPORT 16th May, 1918 South African Ambulance, Hospital Beau Rivage, Dear Sir, Cannes I have to confirm my cable of the 13th instant 7th May, 1918 reading as follows: SISTER ELIZABETH FREUND, late of Luckhoff, "163. Communicate the following to Martin be- Orange Free State, South Africa, affectionately gins Deeply regret to inform you death 4th known to everyone alike as Betty, passed away May Sister Freund full particulars by mail con- at 2 a.m. on Saturday, 4th May, 1918, in her 31 st vey Committee's sympathy to relatives French year. Government have awarded her gold Medaille des Epidemies in recognition of services ren- For some little time back she had not been in a dered Beau Rivage Villa Felicie March aver- very good state of health, but her valiant spirit age 97 27 respectively. - Grew. refused to recognise defeat and she cour- MilLAR," ageously stuck to her duty long after she ought to have given up. Ten weeks ago however, even her determination was forced to give way and and to enclose, for your information and trans- she took to her bed. -

Juta Law Publishing

ADVERTORIAL Supporting the judiciary: Juta Law Publishing century has gone by since the South appointed by President Paul Kruger as Johannesburg’s first criminal African judiciary was instituted follow- magistrate (at the age of 19). He rose to become Chief Magistrate A of Johannesburg and was a founder of the Rand Club. Juta Street in ing Union in 1910. Juta is honoured to have Braamfontein, Johannesburg, was named after the family. been, over the whole of this period, the The Duncan family, which became dominant in the firm during the publisher of legal works reflecting the great 20th century, also produced a lawyer of distinction who was at the heart of a landmark battle in South African law (the famous Harris political and social challenges confronting the cases; AD judgments reported at SALR 1952 (2) SA 428 (A) and 1952 country, and the continuing endeavour of our (4) SA 769 (A)). Graeme Duncan QC argued before the Appellate Division in 1952 that laws made by Parliament in the early 1950s to courts to interpret the law and to assist in its deprive Coloured people of the limited franchise that they had at the development. time were invalid. He succeeded, and successive courts ruled against The house of Juta was founded in Cape Town in 1853 by Jan Carel the government. Although the government ultimately got round the Juta, an immigrant newly arrived from the Netherlands. From a very legal restrictions, in the Harris judgments the courts demonstrated early time, Juta has been closely associated with the development and an independence and an adherence to principle that have become a practice of the law in South Africa. -

A Period of Transition

A PERIOD OF TRANSITION P. HISTORY OF GRAHAMSTOWN 1902-1918 A thesis for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS by Nicholas Derek Southey The writer wishes to express his gratitude to the Ernest Oppenheimer Memorial Trust for a Scholarship for 1820 Settler and Eastern Cape History. The financial assistance of the Human Sciences Research Council is also acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions reached are those of the author and are entirely independent of both these organizations. RHODES UNIVERSITY GR AHAMSTOWN 1984 ii T ABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THE FOOTNOTES iv PREFACE v CHAPTER 1 Municipal Status: A Changing Framework 1 CHAPTER 2 Commercial and Economic Decline 33 CHAPTER 3 Municipal Finance 87 CHAPTER 4 Public Works 113 CHAPTER 5 Sanitation and Public Health 145 CHAPTER 6 Black Grahamstown: "A Dis~race to Civilization" 187 CHAPTER 7 Politics in Flux 257 CHAPTER 8 Conclusion 324 APPENDICES A Population of Grahamstown 1891-1921 352 B Mayors of Grahamstown 1901-1919 354 C Grahamstown Representatives in Parliament 1904-1918 360 D Manifesto of the Eastern Province Association 363 E Some Specimens of Earnings: salaries of artisans and 365 unskilled employees in Grahamstown (1915) F Two verses to commemorate the centenary of Grahamstown in 367 1912 G Map based on Plan of the City of Grahamstown, by Ernest 371a Grubb, City Engineer, Grahamstown, January 1909. BIBLIOGRAPHY 372 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am grateful to the many people who, by the assistance they have given me, have enabled the completion of this thesis. Cory Librarians, Mr Michael Berning and Mrs Sandra Fold, assisted by Dr Mandy Goedhals, Mr Jackson Vena and Mrs Sally Poole, were at all times unstinting with their time, advice and concern, and am grateful to them for making the Cory Library such a pleasant place in which to research. -

Sakeman En Politikus Aan Die Kaap 1859 –1931

Sir David Pieter de Villiers Graaff: Sakeman en Politikus aan die Kaap 1859 –1931 Ebbe Dommisse Proefskrif ingelewer vir die graad Doktor in die Wysbegeerte (Geskiedenis) in die Fakulteit Lettere en Sosiale Wetenskappe aan die Universiteit van Stellenbosch Promotor: Prof A M Grundlingh Desember 2011 University of Stellenbosch: http://scholar.sun.ac.za 1 Kopiereg © 2011 Universiteit van Stellenbosch Alle regte voorbehou University of Stellenbosch: http://scholar.sun.ac.za 2 Opsomming Hierdie studie is ‘n biografie van sir David Pieter de Villiers Graaff, die baronet van Kaapstad wat in 1859 gebore en in 1931 oorlede is. Dit dek sy hele lewensloop, van sy geboorte-uur as arm plaasseun in die distrik van Villiersdorp totdat hy as een van Suid-Afrika se innoverendste sakemanne gesterf het nadat hy hom ook in ‘n politieke loopbaan onderskei het. As die pionier van koelbewaring in Suid-Afrika het hy teen die einde van die negentiende eeu die verkoeling van vleis en voedsel op groot skaal na die land gebring en in die vleisbedryf een van die grootste sakeondernemings in die Suidelike Halfrond opgebou. As burgemeester van Kaapstad op die jeugdige ouderdom van 31 het hy ‘n deurslaggewende bydrae tot die modernisering van die stad gelewer. As lid van genl. Louis Botha se eerste Kabinet na Uniewording in 1910, ‘n bepalende gebeurtenis waardeur die landsgrense van die huidige Republiek van Suid-Afrika vasgelê is, het hy ‘n soms onderskatte rol in die opgang van die land en die landsekonomie na die beproewinge en langtermyn-gevolge van die Anglo-Boere-oorlog gespeel. Die lewensverhaal van hierdie komplekse sakeleier-politikus, ‘n Kaapse Afrikaner wat as vrygesel op gevorderde leeftyd ‘n erflike Britse titel ontvang het en daarna met die dogter van die leraar van sy NG gemeente getroud is, is boonop ‘n boeiende voorbeeld van die moeilike keuses wat Kaapse Afrikaners in koloniale tye tussen trou aan die Britse Ryk en verankering in die Suid- Afrikaanse bodem moes maak. -

THE FOUNDATIONS of ANTISEMITISM in SOUTH AFRICA IMAGES of the JEW C.1870-1930

THE FOUNDATIONS OF ANTISEMITISM IN SOUTH AFRICA IMAGES OF THE JEW c.1870-1930 by MILTON SHAIN M.A.(S.A.); S.T.D. (U.C.T.); M.A.(LEEDS) A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the UniversityDepartment of Cape of History Town University of Cape Town February 1990 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town To take only the subject of the Jews, it would be difficult to find a form of bad reasoning about them which has not been heard in conversation or been admitted to the dignity of print. - George Eliot 1 CONTENTS PAGE ASTRACT i PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv CHAPTER ONE: Introduction 1 CHAPTER TWO: Gentlemen and Knaves The Ambivalent Image 19 CHAPTER THREE: "Where the Carcass is, there shal 1 the Eagles be Gathered Together" : Pedlars, Peruvians and Plutocrats 45 CHAPTER FOUR: From Pariah to Parvenu : The Making of a Stereotype 117 CHAPTER FIVE: Shirkers and Subversives Embellishing the Jewish Stereotype 186 CHAPTER SIX: The Rand Rebellion : Consolidating the Jewish Stereotype 22L CHAPTER SEVEN: "The Jews are Everywhere Climbing to the Top of the Trees Where the Plums are to be Found" : Ou ts iders and Intruders 271 CHAPTER EIGHT: Conclusions : Reappraising Anti- semitism in the Nineteen Thirties and Early Forties 332 APPENDIX I 352 APPENDIX II 363 BIBLIOGRAPHY 366 ii ABSTRACT Historians of South African Jewry have depicted antisemitism in the 1930s and early 1940s as essentially an alien phenomenon, a product of Nazi propaganda at a time of great social and economic trauma. -

Pressure on Goldstone to Repair His Report's Damage to Israel

CHING YUN HU SHOWS BRILLIANT VIRTUOSIC SKILLS / 12 WRITING, BUT AN OVER- VINTAGE PIPPI STILL POPULATED STEALS HEARTS / 12 DESK / 13 Subscribe to our FREE epaper - go to www.sajewishreport.co.za www.sajewishreport.co.za Friday, 8 April 2011 / 4 Nissan, 5771 Volume 15 Number 13 Pressure on Goldstone to repair his Report’s damage to Israel PAGE 3, 8-9 PHOTO: ILAN OSSENDRYVER PHOTO: Dr Clive Evian is a world expert on Aids and a tireless fighter IN THE FOREFRONT OF SOUTH against this pandemic which is wreaking havoc in South Africa. He is a pioneer in the surveillance, prevention and treatment of the AFRICA’S FIGHT AGAINST AIDS disease. He is a true builder of a better South Africa. SEE PAGE 11 UJ scampers to Travel in Mexico - friendly DAVIS: Criticising Israel Israel house prices limit BGU fallout / 4 haven for Jews / 16 doesn’t make an enemy / 10 rise steadily / 5 YOUTH / 18-19 SPORTS / 24 LETTERS / 14 CROSSWORD & BRIDGE / 20 COMMUNITY BUZZ / 7 WHAT’S ON / 20 2 SA JEWISH REPORT 08 - 15 April 2011 SHABBAT TIMES PARSHA OF THE WEEK April 8/4 Nissan April 9/5 Nissan Owen Metzorah Birds of peace Griffith; Starts Ends Ann Harris; 17:42 18:30 Johannesburg WORDS CREATE reality. The Hebrew and Rabbi word for speech, dibur, is the same word 18:10 19:05 Cape Town Moshe for “thing”, davar. And so we read in this 17:27 18:16 Durban Silberhaft. 17:47 18:36 Bloemfontein week’s Torah reading that one who slan- PARSHAT 17:46 18:36 Port Elizabeth dered would be afflicted with a skin con- 17:38 18:28 East London dition that would render him a metzo- METZORAH rah. -

Bibliography of the Publications of J.C. Juta and J.C. Juta & Co 1853-1903

BIBLIOGRAPHY OF T'dE PUBLICATIONS OF J. C. J U T A and J. C. J U T A & Co. 1853-1903 by A.B. Caine and L. Leipoldt. University of Cape Town School of Librarianship University of Cape Town. 1954. The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town ii. PREFACE This is not a comprehensive bibliography of Juta publications for the period 1853 to 1903; indeed we doubt whether it is a complete record of the publica- tions to be found in Cape Town - and no attempt has been made to trace publications in other centres. Certain sources in Cape To~m have not been investigated at all - for example, advertisements in newspapers were not sought for beyond 188 3 and then the search was confined to four newspapers, published in Cape Town. A check on some1the advertisements thus found revealed that Juta's hardly advertised at all in the Eastern province during this period, but a similar check on the Dutch papers originating in Cape Town held more promise. But these researches were abandoned in favour of the more fruitful fields of African.a collections and periodicals of the time. Reviews, and to a lesser extent advertisements, proved to be a trying source of information as there was often no clear distinction made between the bookselling and book-publishing functions of local firms. -

Juta and Company Is the Oldest Publishing House

Corporate Heritage Profi le Juta and Company uta and Company is the oldest publishing house Jin South Africa, and may well be South Africa’s oldest unlisted public company still in existence today. Remarkably, the company remains true to its initial intent to service education and information requirements, and for close on 160 years Juta and Company has been especially associated with Law, Education and Academic publishing and retailing. Drawing on its heritage of authority and excellence, Juta has remained relevant by retaining its entrepreneurial spirit of embracing technological innovation and diversifying beyond publishing and retail into training, e-learning and technology-driven information solutions. The history of Juta is in many ways the history of publishing and book retailing in South Africa. Jan Carel Juta was an enterprising young Dutchman. Trained in Law and married to Karl Marx’s sister, he sailed to the Cape where, By 1857 JC Juta had moved to 2 Wale Street, Cape Town in 1853, he established a company that would be described What was said by Sir John Kotze of Jan Carel Juta might well be said of the company he founded, “He has left us an example of what can be achieved by perseverance, devotion to duty and honourable commercial effort.” JC Juta started publishing legal journals as far back as 1864. That era also marked the beginning of the connection between Juta and education that continues to this day 58 Juta and Company constant theme is the enterprise, determination 158 Years of the Juta brand and integrity of the people who succeeded Jan Responding to the market and Carel Juta. -

Gold Fields Collection

CORY LIBRARY FOR HISTORICAL RESEARCH REGISTER OF DOCUMENTS NO. 27 GOLD FIELDS COLLECTION RHODES UNIVERSITY GRAHAMSTOWN 1981 CORY LIBRARY FOR HISTORICAL RESEARCH REGISTER 0? DOCUMENTS NO. 27 GOLD FIELDS COLLECTION GRAHAMSTOWN 1981 CONTENTS A. Manuscripts anddocuoents ................ ............. 1. B. Pictorial aaterial .................................. *»1. C. Paaphlets......................... 71*. I. Maps .............................. 99. E. Newspapers............................................ 1 1 6 T. Artefacts .................. 117 The documentb described in this Register are the "non-book" materials from the collection presented to Rhodes University for the Cory Library by Gold Fields of South Africa Ltd. It contains manuscripts and documents, books, photographs, newspapers, pamphlets, maps and memorabilia. These materials were assembled from 191*1*- onwards by the firm as a Rhodes Memorial Library and Museum. This Library was established to cover the history and traditions of the Company and its subsidiaries, successors to the original Rhodes, Rudd and Caldecott Syndicate, with special reference to Cecil John Rhodes. The establishment took place as the Company was nearing its 60th Anniversary and Mr F.C.M. Bawden, who was in 'charge from the early days until his death in 1 9 6 8 was able to build up the collection both by purchase and by assembling materials in the records of Gold Fields and its subsidiaries. In 1976 Gold Fields decided that the Collection should be made available to researchers and chose Rhodes University as the most appropriate institution through which to do this. At the time of the deposit in the Cory Library the University Librarian, Dr. F.G. van der Riot, commented, "I think that this is about the biggest gift that has come to the Cory Library since it was first established with the Cory Collection." The sise of the deposit was a major factor in the decision to retain the usual policy for these Registers and to list only the "non-book" Items here.