Acute Dyspnea in the Office ROGER J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clinical Features of Acute Epiglottitis in Adults in the Emergency Department

대한응급의학회지 제 27 권 제 1 호 � 원저� Volume 27, Number 1, February, 2016 Eye, Ear, Nose & Oral Clinical Features of Acute Epiglottitis in Adults in the Emergency Department Department of Emergency Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Dongguk University Ilsan Hospital, Goyang, Gyeonggi-do1, Korea Kyoung Min You, M.D., Woon Yong Kwon, M.D., Gil Joon Suh, M.D., Kyung Su Kim, M.D., Jae Seong Kim, M.D.1, Min Ji Park, M.D. Purpose: Acute epiglottitis is a potentially fatal condition Key Words: Epiglottitis, Emergency medical services, Fever, that can result in airway obstruction. The aim of this study is Intratracheal Intubation to examine the clinical features of adult patients who visited the emergency department (ED) with acute epiglottitis. Methods: This retrospective observational study was con- Article Summary ducted at a single tertiary hospital ED from November 2005 What is already known in the previous study to October 2015. We searched our electronic medical While the incidence of acute epiglottitis in children has records (EMR) system for a diagnosis of “acute epiglottitis” shown a marked decrease as a result of vaccination for and selected those patients who visited the ED. Haemophilus influenzae type b, the incidence of acute Results: A total of 28 patients were included. There was no epiglottitis in adults has increased. However, in Korea, few pediatric case with acute epiglottitis during the study period. studies concerning adult patients with acute epiglottitis The mean age of the patients was 58.0±14.8 years. The who present to the emergency department (ED) have been peak incidences were in the sixth (n=7, 25.0%) and eighth reported. -

Table of Contents

viii Contents Chapter 1. Taking the Certification Examination . 1 General Suggestions for Preparing for the Exam About the Certification Exams Chapter 2. Developmental and Behavioral Sciences . 11 Mary Jo Gilmer, PhD, MBA, RN-BC, FAAN, and Paula Chiplis, PhD, RN, CPNP Psychosocial, Cognitive, and Ethical-Moral Development Behavior Modification Physical Development: Normal Growth Expectations and Developmental Milestones Family Concepts and Issues Family-Centered Care Cultural and Spiritual Diversity Chapter 3. Communication . 23 Mary Jo Gilmer, PhD, MBA, RN-BC, FAAN, and Karen Corlett, MSN, RN-BC, CPNP-AC/PC, PNP-BC Culturally Sensitive Communication Components of Therapeutic Communication Communication Barriers Modes of Communication Patient Confidentiality Written Communication in Nursing Practice Professional Communication Advocacy Chapter 4. The Nursing Process . 33 Clara J. Richardson, MSN, RN–BC Nursing Assessment Nursing Diagnosis and Treatment Chapter 5. Basic and Applied Sciences . 49 Mary Jo Gilmer, PhD, MBA, RN-BC, FAAN, and Paula Chiplis, PhD, RN, CPNP Trauma and Diseases Processes Common Genetic Disorders Common Childhood Diseases Traction Pharmacology Nutrition Chemistry Clinical Signs Associated With Isotonic Dehydration in Infants ix Chapter 6. Educational Principles and Strategies . 69 Mary Jo Gilmer, PhD, MBA, RN-BC, FAAN, and Karen Corlett, MSN, RN-BC, CPNP-AC/PC, PNP-BC Patient Education Chapter 7. Life Situations and Adaptive and Maladaptive Responses . 75 Mary Jo Gilmer, PhD, MBA, RN-BC, FAAN, and Karen Corlett, MSN, RN-BC, CPNP-AC/PC, PNP-BC Palliative Care End-of-Life Care Response to Crisis Chapter 8. Sensory Disorders . 87 Clara J. Richardson, MSN, RN–BC Developmental Characteristics of the Pediatric Sensory System Hearing Disorders Vision Disorders Conjunctivitis Otitis Media and Otitis Externa Retinoblastoma Trauma to the Eye Chapter 9. -

Slipping Rib Syndrome

Slipping Rib Syndrome Jackie Dozier, BS Edited by Lisa E McMahon, MD FACS FAAP David M Notrica, MD FACS FAAP Case Presentation AA is a 12 year old female who presented with a 7 month history of right-sided chest/rib pain. She states that the pain was not preceded by trauma and she had never experienced pain like this before. She has been seen in the past by her pediatrician, chiropractor, and sports medicine physician for her pain. In May 2012, she was seen in the ER after having manipulations done on her ribs by a sports medicine physician. Pain at that time was constant throughout the day and kept her from sleeping. However, it was relieved with hydrocodone/acetaminophen in the ER. Case Presentation Over the following months, the pain became progressively worse and then constant. She also developed shortness of breath. She is a swimmer and says she has had difficulty practicing due to the pain and SOB. AA was seen by a pediatric surgeon and scheduled for an interventional pain management service consult for a test injection. Following good temporary relief by local injection, she was scheduled costal cartilage removal to treat her pain. What is Slipping Rib Syndrome? •Slipping Rib Syndrome (SRS) is caused by hypermobility of the anterior ends of the false rib costal cartilages, which leads to slipping of the affected rib under the superior adjacent rib. •SRS an lead to irritation of the intercostal nerve or strain of the muscles surrounding the rib. •SRS is often misdiagnosed and can lead to months or years of unresolved abdominal and/or thoracic pain. -

Signs and Symptoms of COPD

American Thoracic Society PATIENT EDUCATION | INFORMATION SERIES Signs and Symptoms of COPD Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) can cause shortness of breath, tiredness, Short ness of Breath production of mucus, and cough. Many people with COPD develop most if not all, of these signs Avo iding Activities and symptoms. Sho rtness wit of Breath h Man s Why is shortness of breath a symptom of COPD? y Activitie Shortness of breath (or breathlessness) is a common Avoiding symptom of COPD because the obstruction in the A breathing tubes makes it difficult to move air in and ny Activity out of your lungs. This produces a feeling of difficulty breathing (See ATS Patient Information Series fact sheet Shor f B tness o on Breathlessness). Unfortunately, people try to avoid this reath Sitting feeling by becoming less and less active. This plan may or Standing work at first, but in time it leads to a downward spiral of: avoiding activities which leads to getting out of shape or becoming deconditioned, and this can result in even more Is tiredness a symptom of COPD? shortness of breath with activity (see diagram). Tiredness (or fatigue) is a common symptom in COPD. What can I do to treat shortness of breath? Tiredness may discourage you from keeping active, which leads to greater loss of energy, which then leads to more If your shortness of breath is from COPD, you can do several tiredness. When this cycle begins it is sometimes hard to things to control it: break. CLIP AND COPY AND CLIP ■■ Take your medications regularly. -

Risk of Acute Epiglottitis in Patients with Preexisting Diabetes Mellitus: a Population- Based Case–Control Study

RESEARCH ARTICLE Risk of acute epiglottitis in patients with preexisting diabetes mellitus: A population- based case±control study Yao-Te Tsai1,2, Ethan I. Huang1,2, Geng-He Chang1,2, Ming-Shao Tsai1,2, Cheng- Ming Hsu1,2, Yao-Hsu Yang3,4,5, Meng-Hung Lin6, Chia-Yen Liu6, Hsueh-Yu Li7* 1 Department of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Chiayi, Taiwan, 2 College of Medicine, Chang Gung University, Taoyuan, Taiwan, 3 Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Chiayi, Taiwan, 4 Institute of Occupational Medicine and a1111111111 Industrial Hygiene, National Taiwan University College of Public Health, Taipei, Taiwan, 5 School of a1111111111 Traditional Chinese Medicine, College of Medicine, Chang Gung University, Taoyuan, Taiwan, 6 Health a1111111111 Information and Epidemiology Laboratory, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Chiayi, Taiwan, 7 Department of a1111111111 Otolaryngology±Head and Neck Surgery, Linkou Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taoyuan, Taiwan a1111111111 * [email protected] Abstract OPEN ACCESS Citation: Tsai Y-T, Huang EI, Chang G-H, Tsai M-S, Hsu C-M, Yang Y-H, et al. (2018) Risk of acute Objective epiglottitis in patients with preexisting diabetes Studies have revealed that 3.5%±26.6% of patients with epiglottitis have comorbid diabetes mellitus: A population-based case±control study. PLoS ONE 13(6): e0199036. https://doi.org/ mellitus (DM). However, whether preexisting DM is a risk factor for acute epiglottitis remains 10.1371/journal.pone.0199036 unclear. In this study, our aim was to explore the relationship between preexisting DM and Editor: Yu Ru Kou, National Yang-Ming University, acute epiglottitis in different age and sex groups by using population-based data in Taiwan. -

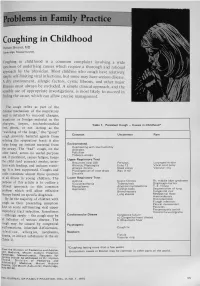

Problems in Family Practice

problems in Family Practice Coughing in Childhood Hyman Sh ran d , M D Cambridge, M assachusetts Coughing in childhood is a common complaint involving a wide spectrum of underlying causes which require a thorough and rational approach by the physician. Most children who cough have relatively simple self-limiting viral infections, but some may have serious disease. A dry environment, allergic factors, cystic fibrosis, and other major illnesses must always be excluded. A simple clinical approach, and the sensible use of appropriate investigations, is most likely to succeed in finding the cause, which can allow precise management. The cough reflex as part of the defense mechanism of the respiratory tract is initiated by mucosal changes, secretions or foreign material in the pharynx, larynx, tracheobronchial Table 1. Persistent Cough — Causes in Childhood* tree, pleura, or ear. Acting as the “watchdog of the lungs,” the “good” cough prevents harmful agents from Common Uncommon Rare entering the respiratory tract; it also helps bring up irritant material from Environmental Overheating with low humidity the airway. The “bad” cough, on the Allergens other hand, serves no useful purpose Pollution Tobacco smoke and, if persistent, causes fatigue, keeps Upper Respiratory Tract the child (and parents) awake, inter Recurrent viral URI Pertussis Laryngeal stridor feres with feeding, and induces vomit Rhinitis, Pharyngitis Echo 12 Vocal cord palsy Allergic rhinitis Nasal polyp Vascular ring ing. It is best suppressed. Coughs and Prolonged use of nose drops Wax in ear colds constitute almost three quarters Sinusitis of all illness in young children. The Lower Respiratory Tract Asthma Cystic fibrosis Rt. -

The Effects of Inhaled Albuterol in Transient Tachypnea of the Newborn Myo-Jing Kim,1 Jae-Ho Yoo,1 Jin-A Jung,1 Shin-Yun Byun2*

Original Article Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2014 March;6(2):126-130. http://dx.doi.org/10.4168/aair.2014.6.2.126 pISSN 2092-7355 • eISSN 2092-7363 The Effects of Inhaled Albuterol in Transient Tachypnea of the Newborn Myo-Jing Kim,1 Jae-Ho Yoo,1 Jin-A Jung,1 Shin-Yun Byun2* 1Department of Pediatrics, Dong-A University, College of Medicine, Busan, Korea 2Department of Pediatrics, Pusan National University School of Medicine, Yangsan, Korea This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Purpose: Transient tachypnea of the newborn (TTN) is a disorder caused by the delayed clearance of fetal alveolar fluid.ß -adrenergic agonists such as albuterol (salbutamol) are known to catalyze lung fluid absorption. This study examined whether inhalational salbutamol therapy could improve clinical symptoms in TTN. Additional endpoints included the diagnostic and therapeutic efficacy of salbutamol as well as its overall safety. Methods: From January 2010 through December 2010, we conducted a prospective study of 40 newborns hospitalized with TTN in the neonatal intensive care unit. Patients were given either inhalational salbutamol (28 patients) or placebo (12 patients), and clinical indices were compared. Results: The dura- tion of tachypnea was shorter in patients receiving inhalational salbutamol therapy, although this difference was not statistically significant. The dura- tion of supplemental oxygen therapy and the duration of empiric antibiotic treatment were significantly shorter in the salbutamol-treated group. -

CT Children's CLASP Guideline

CT Children’s CLASP Guideline Chest Pain INTRODUCTION . Chest pain is a frequent complaint in children and adolescents, which may lead to school absences and restriction of activities, often causing significant anxiety in the patient and family. The etiology of chest pain in children is not typically due to a serious organic cause without positive history and physical exam findings in the cardiac or respiratory systems. Good history taking skills and a thorough physical exam can point you in the direction of non-cardiac causes including GI, psychogenic, and other rare causes (see Appendix A). A study performed by the New England Congenital Cardiology Association (NECCA) identified 1016 ambulatory patients, ages 7 to 21 years, who were referred to a cardiologist for chest pain. Only two patients (< 0.2%) had chest pain due to an underlying cardiac condition, 1 with pericarditis and 1 with an anomalous coronary artery origin. Therefore, the vast majority of patients presenting to primary care setting with chest pain have a benign etiology and with careful screening, the patients at highest risk can be accurately identified and referred for evaluation by a Pediatric Cardiologist. INITIAL INITIAL EVALUATION: Focused on excluding rare, but serious abnormalities associated with sudden cardiac death EVALUATION or cardiac anomalies by obtaining the targeted clinical history and exam below (red flags): . Concerning Pain Characteristics, See Appendix B AND . Concerning Past Medical History, See Appendix B MANAGEMENT . Alarming Family History, See Appendix B . Physical exam: - Blood pressure abnormalities (obtain with manual cuff, in sitting position, right arm) - Non-innocent murmurs . Obtain ECG, unless confident pain is musculoskeletal in origin: - ECG’s can be obtained at CT Children’s main campus and satellites locations daily (Hartford, Danbury, Glastonbury, Shelton). -

Chapter 17 Dyspnea Sabina Braithwaite and Debra Perina

Chapter 17 Dyspnea Sabina Braithwaite and Debra Perina ■ PERSPECTIVE Pathophysiology Dyspnea is the term applied to the sensation of breathlessness The actual mechanisms responsible for dyspnea are unknown. and the patient’s reaction to that sensation. It is an uncomfort- Normal breathing is controlled both centrally by the respira- able awareness of breathing difficulties that in the extreme tory control center in the medulla oblongata, as well as periph- manifests as “air hunger.” Dyspnea is often ill defined by erally by chemoreceptors located near the carotid bodies, and patients, who may describe the feeling as shortness of breath, mechanoreceptors in the diaphragm and skeletal muscles.3 chest tightness, or difficulty breathing. Dyspnea results Any imbalance between these sites is perceived as dyspnea. from a variety of conditions, ranging from nonurgent to life- This imbalance generally results from ventilatory demand threatening. Neither the clinical severity nor the patient’s per- being greater than capacity.4 ception correlates well with the seriousness of underlying The perception and sensation of dyspnea are believed to pathology and may be affected by emotions, behavioral and occur by one or more of the following mechanisms: increased cultural influences, and external stimuli.1,2 work of breathing, such as the increased lung resistance or The following terms may be used in the assessment of the decreased compliance that occurs with asthma or chronic dyspneic patient: obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), or increased respira- tory drive, such as results from severe hypoxemia, acidosis, or Tachypnea: A respiratory rate greater than normal. Normal rates centrally acting stimuli (toxins, central nervous system events). -

Breathing Better with a COPD Diagnosis

Difficulty Breathing Chronic Bronchitis Smoker’s Cough Chronic Coughing Wheezing Em- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease physema Shortness of Breath Feeling of Suffocation Excess Mucus Difficulty Breathing Chronic Bronchitis Smoker’s Cough Chronic Coughing Wheezing Emphysema Shor tness of Breath Feeling of Suffocation Excess Mucus Difficulty Breathing Chronic Bronchitis Smoker’s Cough Chronic Coughing Wheezing Emphysema Shortness of Breath Feeling of Suffocation Excess Mucus Difficulty Breathing Chronic Bronchitis Smoker’s Cough Chron- ic Coughing Wheezing Emphysema Shortness of Breath Feeling of Suffocation Excess Mu- cus DifficultyBreathing Breathing Chronic Bronchitis Better Smoker’s Cough Chronic Coughing Wheezing Emphysema Shortness of Breath Feeling of Suffocation Excess Mucus Difficulty Breathing Chronic Bronchitis Smoker’s Cough Chronic Coughing Wheezing Emphysema Shor tness of Breath Feeling of SuffocationWith Excess a COPDMucus Difficulty Diagnosis Breathing Chronic Bronchitis Smoker’s Cough Chronic Coughing Wheezing Emphysema Shortness of Breath Feeling of did you know? When COPD is severe, shortness of breath and other COPDdid you is the know? 4th leading cause of death in the symptomswhen you can get are in the diagnosed way of doing even the most UnitedCOPD States.is the 4th The leading disease cause kills ofmore death than in 120,000 basicwith tasks, copd such as doing light housework, taking a Americansthe United eachStates year—that’s and causes 1 serious, death every long-term 4 walk,There and are even many bathing things and that getting you can dressed. do to make minutes—anddisability. The causesnumber serious, of people long-term with COPDdisability. is COPDliving withdevelops COPD slowly, easier: and can worsen over time, increasing.The number More of people than 12with million COPD people is increasing. -

Rivaroxaban (Xarelto®)

Rivaroxaban (Xarelto®) To reduce your bleeding and clotting risk it is important that you attend follow-up appointments with your provider, and have blood tests done as your provider orders. What is rivaroxaban (Xarelto®)? • Rivaroxaban is also called Xarelto® • Rivaroxaban(Xarelto®) is used to reduce the risk of blood clots and stroke in people with an abnormal heart rhythm known as atrial fibrillation, in people who have had a blood clot, or in people who have undergone orthopedic surgery. o Blood clots can block a blood vessel cutting off blood supply to the area. o Rarely, clots can break into pieces and travel in the blood stream, lodging in the heart (causing a heart attack), the lungs (causing a pulmonary embolus), or in the brain (causing a stroke). • If you were previously on Warfarin/Coumadin® and you are starting Rivaroxaban(Xarelto®), do not continue taking warfarin. Rivaroxaban(Xarelto®) replaces warfarin. Xarelto 10mg tablet Xarelto 15mg tablet Xarelto 20mg tablet How should I take rivaroxaban (Xarelto®)? • Take Rivaroxaban(Xarelto®) exactly as prescribed by your doctor. • Rivaroxaban(Xarelto®) should be taken with food. • Rivaroxaban(Xarelto®) tablets may be crushed and mixed with applesauce to make the tablet easier to swallow. - 1 - • If you missed a dose: o Take it as soon as you remember on the same day. • Do not stop taking rivaroxaban suddenly without telling your doctor. This can put you at risk of having a stroke or a blood clot. • If you take too much rivaroxaban, call your doctor or the anticoagulation service. If you are experiencing any bleeding which you cannot get to stop, go to the nearest emergency room. -

Central Neurogenic Hyperventilation Related to Post-Hypoxic Thalamic Lesion in a Child

Neurology International 2016; volume 8:6428 Central neurogenic normal. An emergency brain magnetic reso- nance imaging (MRI) was performed. Correspondence: Pinar Gençpinar, Department of hyperventilation related Although there was no apparent lesion in the Pediatric Neurology, Tepecik Training and to post-hypoxic thalamic lesion brain stem, bilateral diffuse thalamic, putami- Research Hospital, Izmir, Turkey. in a child nal and globus palllideal lesions were detected Tel.: +90.505.887.9258. on MRI (Figures 1 and 2). Examination E-mail: [email protected] Pinar Gençpinar,1 Kamil Karaali,2 revealed tachypnea (respiratory rate, 42/min), but other findings were normal. Arterial blood Key words: Central neurogenic hyperventilation; enay Haspolat,3 O uz Dursun4 thalamus; tachypnea; children. Ş ğ gases (ABGs) were pH, 7.52; PaCO2, 29 mmHg; 1Department of Pediatric Neurology, and PaO2, 142 mmHg. The chest radiograph, Contributions: PG prepared the manuscript; KK Tepecik Training of Research Hospital, electrocardiogram, and echocardiogram were prepared the figures and edited in this respect; 2 Izmir; Department of Radiology, normal. Laboratory studies disclosed the fol- OD and SH edited this manuscript and made final 3Department of Pediatric Neurology, lowing values: hematocrit, 33.7%, white blood version. 4Department of Pediatric Intensive Care cell count, 10.6×109/L; sodium, 140 mEq/L; Unit, Akdeniz University Hospital, potassium, 3.7 mEq/L; serum urea nitrogen; 6 Conflict of interest: the authors declare no poten- Antalya, Turkey mg/dL; creatinine, 0.21 mg/ dL; and glucose, tial conflict of interest. 110 mg/dL. Liver transaminases levels were normal. Serum lactate level was 1.97 mmol/L Received for publication: 23 January 2016.