Respiratory Drug Guidelines ______

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clinical Features of Acute Epiglottitis in Adults in the Emergency Department

대한응급의학회지 제 27 권 제 1 호 � 원저� Volume 27, Number 1, February, 2016 Eye, Ear, Nose & Oral Clinical Features of Acute Epiglottitis in Adults in the Emergency Department Department of Emergency Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Dongguk University Ilsan Hospital, Goyang, Gyeonggi-do1, Korea Kyoung Min You, M.D., Woon Yong Kwon, M.D., Gil Joon Suh, M.D., Kyung Su Kim, M.D., Jae Seong Kim, M.D.1, Min Ji Park, M.D. Purpose: Acute epiglottitis is a potentially fatal condition Key Words: Epiglottitis, Emergency medical services, Fever, that can result in airway obstruction. The aim of this study is Intratracheal Intubation to examine the clinical features of adult patients who visited the emergency department (ED) with acute epiglottitis. Methods: This retrospective observational study was con- Article Summary ducted at a single tertiary hospital ED from November 2005 What is already known in the previous study to October 2015. We searched our electronic medical While the incidence of acute epiglottitis in children has records (EMR) system for a diagnosis of “acute epiglottitis” shown a marked decrease as a result of vaccination for and selected those patients who visited the ED. Haemophilus influenzae type b, the incidence of acute Results: A total of 28 patients were included. There was no epiglottitis in adults has increased. However, in Korea, few pediatric case with acute epiglottitis during the study period. studies concerning adult patients with acute epiglottitis The mean age of the patients was 58.0±14.8 years. The who present to the emergency department (ED) have been peak incidences were in the sixth (n=7, 25.0%) and eighth reported. -

Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis As a Cause of Bronchial Asthma in Children

Egypt J Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2012;10(2):95-100. Original article Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis as a cause of bronchial asthma in children Background: Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) occurs in Dina Shokry, patients with asthma and cystic fibrosis. When aspergillus fumigatus spores Ashgan A. are inhaled they grow in bronchial mucous as hyphae. It occurs in non Alghobashy, immunocompromised patients and belongs to the hypersensitivity disorders Heba H. Gawish*, induced by Aspergillus. Objective: To diagnose cases of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis among asthmatic children and define the Manal M. El-Gerby* association between the clinical and laboratory findings of aspergillus fumigatus (AF) and bronchial asthma. Methods: Eighty asthmatic children were recruited in this study and divided into 50 atopic and 30 non-atopic Departments of children. The following were done: skin prick test for aspergillus fumigatus Pediatrics and and other allergens, measurement of serum total IgE, specific serum Clinical Pathology*, aspergillus fumigatus antibody titer IgG and IgE (AF specific IgG and IgE) Faculty of Medicine, and absolute eosinophilic count. Results: ABPA occurred only in atopic Zagazig University, asthmatics, it was more prevalent with decreased forced expiratory volume Egypt. at the first second (FEV1). Prolonged duration of asthma and steroid dependency were associated with ABPA. AF specific IgE and IgG were higher in the atopic group, they were higher in Aspergillus fumigatus skin Correspondence: prick test positive children than negative ones .Wheal diameter of skin prick Dina Shokry, test had a significant relation to the level of AF IgE titer. Skin prick test Department of positive cases for aspergillus fumigatus was observed in 32% of atopic Pediatrics, Faculty of asthmatic children. -

Table of Contents

viii Contents Chapter 1. Taking the Certification Examination . 1 General Suggestions for Preparing for the Exam About the Certification Exams Chapter 2. Developmental and Behavioral Sciences . 11 Mary Jo Gilmer, PhD, MBA, RN-BC, FAAN, and Paula Chiplis, PhD, RN, CPNP Psychosocial, Cognitive, and Ethical-Moral Development Behavior Modification Physical Development: Normal Growth Expectations and Developmental Milestones Family Concepts and Issues Family-Centered Care Cultural and Spiritual Diversity Chapter 3. Communication . 23 Mary Jo Gilmer, PhD, MBA, RN-BC, FAAN, and Karen Corlett, MSN, RN-BC, CPNP-AC/PC, PNP-BC Culturally Sensitive Communication Components of Therapeutic Communication Communication Barriers Modes of Communication Patient Confidentiality Written Communication in Nursing Practice Professional Communication Advocacy Chapter 4. The Nursing Process . 33 Clara J. Richardson, MSN, RN–BC Nursing Assessment Nursing Diagnosis and Treatment Chapter 5. Basic and Applied Sciences . 49 Mary Jo Gilmer, PhD, MBA, RN-BC, FAAN, and Paula Chiplis, PhD, RN, CPNP Trauma and Diseases Processes Common Genetic Disorders Common Childhood Diseases Traction Pharmacology Nutrition Chemistry Clinical Signs Associated With Isotonic Dehydration in Infants ix Chapter 6. Educational Principles and Strategies . 69 Mary Jo Gilmer, PhD, MBA, RN-BC, FAAN, and Karen Corlett, MSN, RN-BC, CPNP-AC/PC, PNP-BC Patient Education Chapter 7. Life Situations and Adaptive and Maladaptive Responses . 75 Mary Jo Gilmer, PhD, MBA, RN-BC, FAAN, and Karen Corlett, MSN, RN-BC, CPNP-AC/PC, PNP-BC Palliative Care End-of-Life Care Response to Crisis Chapter 8. Sensory Disorders . 87 Clara J. Richardson, MSN, RN–BC Developmental Characteristics of the Pediatric Sensory System Hearing Disorders Vision Disorders Conjunctivitis Otitis Media and Otitis Externa Retinoblastoma Trauma to the Eye Chapter 9. -

Khan CV 9-4-20

CURRICULUM VITAE DAVID A. KHAN, MD University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center 5323 Harry Hines Boulevard Dallas, TX 75390-8859 (214) 648-5659 (work) (214) 648-9102 (fax) [email protected] EDUCATION 1980 -1984 University of Illinois, Champaign IL; B.S. in Chemistry, Magna Cum Laude 1984 -1988 University of Illinois School of Medicine, Chicago IL; M.D. 1988 -1991 Good Samaritan Medical Center, Phoenix AZ; Internal Medicine internship & residency 1991-1994 Mayo Clinic, Rochester MN; Allergy & Immunology fellowship PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 1994 -2001 Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine, UT Southwestern 1997 -1998 Co-Director, Allergy & Immunology Training Program 1998 - Director, Allergy & Immunology Training Program 2002- 2008 Associate Professor of Internal Medicine, UT Southwestern 2008-present Professor of Medicine, UT Southwestern AWARDS/HONORS 1993 Allen & Hanburys Respiratory Institute Allergy Fellowship Award 1993 Von Pirquet Award 2001 Outstanding Teacher 2000-2001 UTSW Class of 2003 2004 Outstanding Teacher 2003-2004 UTSW Class of 2006 2005 Outstanding Teacher 2004-2005 UTSW Class of 2007 2006 Daniel Goodman Lectureship, ACAAI meeting 2007 Most Entertaining Teacher 2006-2007 UTSW Class of 2009 2008 Stanislaus Jaros Lectureship, ACAAI meeting 2009 Outstanding Teacher 2007-2008 UTSW Class of 2010 2011 John L. McGovern Lectureship, ACAAI meeting 2012 I. Leonard Bernstein Lecture, ACAAI meeting 2014 Distinguished Fellow, ACAAI meeting 2015 Elliot F. Ellis Memorial Lectureship, AAAAI meeting 2015 Bernard Berman Lectureship, -

Risk of Acute Epiglottitis in Patients with Preexisting Diabetes Mellitus: a Population- Based Case–Control Study

RESEARCH ARTICLE Risk of acute epiglottitis in patients with preexisting diabetes mellitus: A population- based case±control study Yao-Te Tsai1,2, Ethan I. Huang1,2, Geng-He Chang1,2, Ming-Shao Tsai1,2, Cheng- Ming Hsu1,2, Yao-Hsu Yang3,4,5, Meng-Hung Lin6, Chia-Yen Liu6, Hsueh-Yu Li7* 1 Department of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Chiayi, Taiwan, 2 College of Medicine, Chang Gung University, Taoyuan, Taiwan, 3 Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Chiayi, Taiwan, 4 Institute of Occupational Medicine and a1111111111 Industrial Hygiene, National Taiwan University College of Public Health, Taipei, Taiwan, 5 School of a1111111111 Traditional Chinese Medicine, College of Medicine, Chang Gung University, Taoyuan, Taiwan, 6 Health a1111111111 Information and Epidemiology Laboratory, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Chiayi, Taiwan, 7 Department of a1111111111 Otolaryngology±Head and Neck Surgery, Linkou Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taoyuan, Taiwan a1111111111 * [email protected] Abstract OPEN ACCESS Citation: Tsai Y-T, Huang EI, Chang G-H, Tsai M-S, Hsu C-M, Yang Y-H, et al. (2018) Risk of acute Objective epiglottitis in patients with preexisting diabetes Studies have revealed that 3.5%±26.6% of patients with epiglottitis have comorbid diabetes mellitus: A population-based case±control study. PLoS ONE 13(6): e0199036. https://doi.org/ mellitus (DM). However, whether preexisting DM is a risk factor for acute epiglottitis remains 10.1371/journal.pone.0199036 unclear. In this study, our aim was to explore the relationship between preexisting DM and Editor: Yu Ru Kou, National Yang-Ming University, acute epiglottitis in different age and sex groups by using population-based data in Taiwan. -

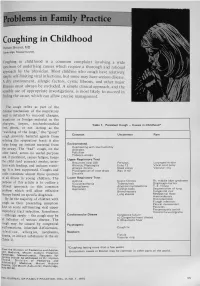

Problems in Family Practice

problems in Family Practice Coughing in Childhood Hyman Sh ran d , M D Cambridge, M assachusetts Coughing in childhood is a common complaint involving a wide spectrum of underlying causes which require a thorough and rational approach by the physician. Most children who cough have relatively simple self-limiting viral infections, but some may have serious disease. A dry environment, allergic factors, cystic fibrosis, and other major illnesses must always be excluded. A simple clinical approach, and the sensible use of appropriate investigations, is most likely to succeed in finding the cause, which can allow precise management. The cough reflex as part of the defense mechanism of the respiratory tract is initiated by mucosal changes, secretions or foreign material in the pharynx, larynx, tracheobronchial Table 1. Persistent Cough — Causes in Childhood* tree, pleura, or ear. Acting as the “watchdog of the lungs,” the “good” cough prevents harmful agents from Common Uncommon Rare entering the respiratory tract; it also helps bring up irritant material from Environmental Overheating with low humidity the airway. The “bad” cough, on the Allergens other hand, serves no useful purpose Pollution Tobacco smoke and, if persistent, causes fatigue, keeps Upper Respiratory Tract the child (and parents) awake, inter Recurrent viral URI Pertussis Laryngeal stridor feres with feeding, and induces vomit Rhinitis, Pharyngitis Echo 12 Vocal cord palsy Allergic rhinitis Nasal polyp Vascular ring ing. It is best suppressed. Coughs and Prolonged use of nose drops Wax in ear colds constitute almost three quarters Sinusitis of all illness in young children. The Lower Respiratory Tract Asthma Cystic fibrosis Rt. -

Asthma Exacerbation Management

CLINICAL PATHWAY ASTHMA EXACERBATION MANAGEMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Figure 1. Algorithm for Asthma Exacerbation Management – Outpatient Clinic Figure 2. Algorithm for Asthma Management – Emergency Department Figure 3. Algorithm for Asthma Management – Inpatient Figure 4. Progression through the Bronchodilator Weaning Protocol Table 1. Pediatric Asthma Severity (PAS) Score Table 2. Bronchodilator Weaning Protocol Target Population Clinical Management Clinical Assessment Treatment Clinical Care Guidelines for Treatment of Asthma Exacerbations Children’s Hospital Colorado High Risk Asthma Program Table 3. Dosage of Daily Controller Medication for Asthma Control Table 4. Dosage of Medications for Asthma Exacerbations Table 5. Dexamethasone Dosing Guide for Asthma Figure 5. Algorithm for Dexamethasone Dosing – Inpatient Asthma Patient | Caregiver Education Materials Appendix A. Asthma Management – Outpatient Appendix B. Asthma Stepwise Approach (aka STEPs) Appendix C. Asthma Education Handout References Clinical Improvement Team Page 1 of 24 CLINICAL PATHWAY FIGURE 1. ALGORITHM FOR ASTHMA EXACERBATION MANAGEMENT – OUTPATIENT CLINIC Triage RN/MA: • Check HR, RR, temp, pulse ox. Triage level as appropriate • Notify attending physician if patient in severe distress (RR greater than 35, oxygen saturation less than 90%, speaks in single words/trouble breathing at rest) Primary RN: • Give oxygen to keep pulse oximetry greater than 90% Treatment Inclusion Criteria 1. Give nebulized or MDI3 albuterol up to 3 doses. Albuterol dosing is 0.15 to 0.3mg/kg per 2007 • 2 years or older NHLBI guidelines. • Treated for asthma or asthma • Less than 20 kg: 2.5 mg neb x 3 or 2 to 4 puffs MDI albuterol x 3 exacerbation • 20 kg or greater: 5 mg neb x 3 or 4 to 8 puffs MDI albuterol x 3 • First time wheeze with history consistent Note: For moderate (dyspnea interferes with activities)/severe (dyspnea at rest) exacerbations you with asthma can add atrovent to nebulized albuterol at 0.5mg/neb x 3. -

NUR 6325 Family Primary Care I Fall Semester 2021 Course Information

NUR 6325 Family Primary Care I Fall Semester 2021 Department of Nursing Instructor: Avis Johnson-Smith, DNP, APRN, FNP-BC, CPNP-PC, CPMHS, CNS, FAANP Email: [email protected] Phone: 229-431-2030 Office: Virtual Office Hours: By Appointment. If you have a question and an email response would suffice, then simply let me know this when you contact me. Time Zone: All due dates and times in this syllabus are Central Standard Time (CST) Course Information Course Description The course focus is on the transition from RN to Family Nurse Practitioner in the diagnosis and management of common acute and chronic conditions across the lifespan in a primary care setting. As a provider of family-centered care emphasis is placed on health promotion, risk reduction and evidence- based management of common symptoms and problems. Nursing’s unique contribution to patient care and collaboration with other health care professionals is emphasized. Course Credits Three semester credit hours (3-0-0) This course meets completely online using Blackboard as the delivery method Prerequisite / Co-requisite Courses NUR 6201, 6318, 6323, 6324, 6331, NUR 6327 Prerequisite Skills Accessing internet web sites, use of ASU Library resources, and proficiency with Microsoft Word and/or PowerPoint are expectations of the program name. Computer access requirements are further delineated in the graduate Handbook. Tutorials for ASU Library and for Blackboard are available through RamPort. The ASU Graduate Nursing Student Handbook1 should be reviewed before taking this course. Program Outcomes Upon completion of the program of study for the MSN Program, the graduate will be prepared to: 1. -

Management of Acute Exacerbation of Asthma and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in the Emergency Department

Management of Acute Exacerbation of Asthma and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in the Emergency Department Salvador J. Suau, MD*, Peter M.C. DeBlieux, MD KEYWORDS Asthma Asthmatic crisis COPD AECOPD KEY POINTS Management of severe asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exac- erbations require similar medical interventions in the acute care setting. Capnography, electrocardiography, chest x-ray, and ultrasonography are important diag- nostic tools in patients with undifferentiated shortness of breath. Bronchodilators and corticosteroids are first-line therapies for both asthma and COPD exacerbations. Noninvasive ventilation, magnesium, and ketamine should be considered in patients with severe symptoms and in those not responding to first-line therapy. A detailed plan reviewed with the patient before discharge can decrease the number of future exacerbations. INTRODUCTION Acute asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbations are the most common respiratory diseases requiring emergent medical evaluation and treatment. Asthma accounts for more than 2 million visits to emergency departments (EDs), and approximately 4000 annual deaths in the United States.1 In a similar fashion, COPD is a major cause of morbidity and mortality. It affects more than 14.2 million Americans (Æ9.8 million who may be undiagnosed).2 COPD accounts for more than 1.5 million yearly ED visits and is the fourth leading cause of death Disclosures: None. Louisiana State University, University Medical Center of New Orleans, 2000 Canal Street, D&T 2nd Floor - Suite 2720, New Orleans, LA 70112, USA * Corresponding author. E-mail address: [email protected] Emerg Med Clin N Am 34 (2016) 15–37 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.emc.2015.08.002 emed.theclinics.com 0733-8627/16/$ – see front matter Ó 2016 Elsevier Inc. -

Defective Regulation of Immune Responses in Croup Due to Parainfluenza Virus

716 WELLIVER ET AL. Science 221: 1067-1070 20. Mawhinney TP, Feather MS, Martinez JR, Barbero GJ 1979 The chronically 17. Quissell DO 1980 Secretory response of dispersed rat submandibular cells: I. reserpinized rat as an animal model for cystic fibrosis: acute effect of Potassium release. Am J Physiol 238:C90-C98 isoproterenol and pilocarpine upon pulmonary lavage fluid. Pediatr Res 18. Lowry OH, Rosebrough NF, Farrar AL, Randall RJ 195 1 Protein measurement 13:760-763 with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem 193:265-268 21. Frizzell RA, Fields M, Schultz SG 1979 Sodium-coupled chloride transport by 19. Perlmutter J, Martinez JR 1978 The chornically reserpinized rat as a possible epithelial tissues. Am J Physiol 236:FI-F8 model for cystic fibrosis: VII. Alterations in the secretory response to secretin 22. Welsh M 1983 Inhibition of chloride secretion by furosemide in canine tracheal and to cholecystokinin from the pancreas in vivo. Pediatr Res 12: 188- 194 epithelium. J Memb Biol71:219-226 003 1-3998/85/1907-07 16$02.00/0 PEDIATRIC RESEARCH Vol. 19, No. 7, 1985 Copyright O 1985 International Pediatric Research Foundation, Inc. Printed in U.S.A. Defective Regulation of Immune Responses in Croup Due to Parainfluenza Virus ROBERT C. WELLIVER, MARTHA SUN, AND DEBORAH RINALDO Department ofPediatrics, State University of New York at Buffalo, and Division of Infectious Diseases, Children S Hospital, Buffalo, New York 14222 ABSTRACT. In order to determine if defects in regulation Croup is a common respiratory illness of childhood, yet fairly of immune responses play a role in the pathogenesis of little is known about its pathogenesis. -

2020 GINA Pocket Guide for Asthma Management and Prevention

POCKET GUIDE FOR ASTHMA MANAGEMENT AND PREVENTION (for Adults and Children Older than 5 Years) DISTRIBUTE OR COPY NOT DO MATERIAL- COPYRIGHTED A Pocket Guide for Health Professionals Updated 2020 BASED ON THE GLOBAL STRATEGY FOR ASTHMA MANAGEMENT AND PREVENTION © 2020 Global Initiative for Asthma GLOBAL INITIATIVE FOR ASTHMA ASTHMA MANAGEMENT AND PREVENTION DISTRIBUTE for adults and children older ORthan 5 years COPY NOT A POCKET GUIDE FOR HEALTHDO PROFESSIONALS MATERIAL-Updated 2020 GINA Science Committee Chair: Helen Reddel, MBBS PhD COPYRIGHTED GINA Board of Directors Chair: Louis-Philippe Boulet, MD GINA Dissemination and Implementation Committee Chair: Mark Levy, MD (to Sept 2019); Alvaro Cruz, MD (from Sept 2019) GINA Assembly The GINA Assembly includes members from many countries, listed on the GINA website www.ginasthma.org. GINA Executive Director Rebecca Decker, BS, MSJ Names of members of the GINA Committees are listed on page 48. 1 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS BDP Beclometasone dipropionate COPD Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease CXR Chest X-ray DPI Dry powder inhaler FeNO Fraction of exhaled nitric oxide FEV1 Forced expiratory volume in 1 second FVC Forced vital capacity GERD Gastroesophageal reflux disease HDM House dust mite ICS Inhaled corticosteroids ICS-LABA Combination ICS and LABA Ig Immunoglobulin IL Interleukin DISTRIBUTE IV Intravenous OR LABA Long-acting beta2-agonist COPY LAMA Long-acting muscarinic antagonist NOT LTRA Leukotriene receptor antagonistDO n.a. Not applicable NSAID Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug MATERIAL- O2 Oxygen OCS Oral corticosteroids PEF Peak expiratory flow pMDI PressurizedCOPYRIGHTED metered dose inhaler SABA Short-acting beta2-agonist SC Subcutaneous SLIT Sublingual immunotherapy 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of abbreviations ........................................................................................ -

1 Respiratory Disorders 1

SECTION 1 Respiratory Disorders 1 Sore Throat Robert R. Tanz Most causes of sore throat are nonbacterial and neither require nor are is rarely reason to test outpatients and infrequent benefit to testing inpa- alleviated by antibiotic therapy (Tables 1.1, 1.2, and 1.3). Accurate tients except to confirm and treat influenza. diagnosis is essential: Acute streptococcal pharyngitis warrants diag- Adenoviruses can cause upper and lower respiratory tract disease, nosis and therapy to ensure prevention of serious suppurative and ranging from ordinary colds to severe pneumonia and multisystem nonsuppurative complications. Life-threatening infectious complica- disease, including hepatitis, myocarditis, and myositis. The incubation tions of oropharyngeal infections, whether streptococcal or nonstrep- period of adenovirus infection is 2-4 days. Upper respiratory tract tococcal, may manifest with mouth pain, pharyngitis, parapharyngeal infection typically produces fever, erythema of the pharynx, and fol- space infectious extension, and/or airway obstruction (Tables 1.4 and licular hyperplasia of the tonsils, together with exudate. Enlargement 1.5). In many cases, the history and/or physical exam can help direct of the cervical lymph nodes occurs frequently. When conjunctivitis diagnosis and treatment, but the enormous number of potential causes occurs in association with adenoviral pharyngitis, the resulting syn- is too large to address all of them. drome is called pharyngoconjunctival fever. Pharyngitis may last as long as 7 days and does not respond to antibiotics. There are many adenovirus serotypes; adenovirus infections may therefore develop in VIRAL PHARYNGITIS children more than once. Laboratory studies may reveal a leukocytosis and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Adenovirus outbreaks Most episodes of pharyngitis are caused by viruses (see Tables 1.2 and have been associated with swimming pools and contamination in 1.3).