Community Resources and Black Social Action, F Street, a Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Film Appreciation Wednesdays 6-10Pm in the Carole L

Mike Traina, professor Petaluma office #674, (707) 778-3687 Hours: Tues 3-5pm, Wed 2-5pm [email protected] Additional days by appointment Media 10: Film Appreciation Wednesdays 6-10pm in the Carole L. Ellis Auditorium Course Syllabus, Spring 2017 READ THIS DOCUMENT CAREFULLY! Welcome to the Spring Cinema Series… a unique opportunity to learn about cinema in an interdisciplinary, cinematheque-style environment open to the general public! Throughout the term we will invite a variety of special guests to enrich your understanding of the films in the series. The films will be preceded by formal introductions and followed by public discussions. You are welcome and encouraged to bring guests throughout the term! This is not a traditional class, therefore it is important for you to review the course assignments and due dates carefully to ensure that you fulfill all the requirements to earn the grade you desire. We want the Cinema Series to be both entertaining and enlightening for students and community alike. Welcome to our college film club! COURSE DESCRIPTION This course will introduce students to one of the most powerful cultural and social communications media of our time: cinema. The successful student will become more aware of the complexity of film art, more sensitive to its nuances, textures, and rhythms, and more perceptive in “reading” its multilayered blend of image, sound, and motion. The films, texts, and classroom materials will cover a broad range of domestic, independent, and international cinema, making students aware of the culture, politics, and social history of the periods in which the films were produced. -

PDF (1.06 Mib)

The Ten Best Movies of the 4. Pulp Fiction '94: Quentin Tarantino's follow-up to Reservoir Dogs was nothing short of spectacular as its unique blend of shocking violence and 1990s: side splitting laughs caused a massive stir at Cannes. Rapid fire style cou- pled with first class writing paved the way for a genre of film still prevalent 10. GOOdfellaS '90: True account of Henry Hill, Jimmy Conway, and Tommy in the industry today. De Vito and their mobster lives in New York during the '60s and '70s. Not The Godfather, but Scorsese's work is explosive, well-acted, and has some- 3. The Ice Storm '97: The best movie you didn't see. As Vietnam approach- thing that many films don't: mass appeal. es its terminus and the Watergate scandal unfolds, life in the real world is in a cocked hat. Beautifully written tale of sexual exploration as well as the 9. Fearless '93: Excellent introspective journey by director Peter Weir into search for meaning and genuine satisfaction outside of socially mandated the psyche of a plane crash survivor and his mental transformation. Deeply boundaries. moving performance from Jeff Bridges. 2. Lost Highway '97: David Lynch's journey into the depths of the mind 8. The Usual Suspects '95: Bryan Singer's taut crime drama features the made for one creepy film. Fred Madison, after being accused of murder, mys- best ensemble cast this side of Glengary Glen Ross. Gabriel Byrne, Stephen teriously morphs into Pete Dayton. Soon the two sides of the alter ego begin Baldwin, Benicio Del Toro, Kevin Pollak, Kevin Spacey and Chazz Palminteri to cross paths in a surreal web of intrigue. -

Teaching Social Studies Through Film

Teaching Social Studies Through Film Written, Produced, and Directed by John Burkowski Jr. Xose Manuel Alvarino Social Studies Teacher Social Studies Teacher Miami-Dade County Miami-Dade County Academy for Advanced Academics at Hialeah Gardens Middle School Florida International University 11690 NW 92 Ave 11200 SW 8 St. Hialeah Gardens, FL 33018 VH130 Telephone: 305-817-0017 Miami, FL 33199 E-mail: [email protected] Telephone: 305-348-7043 E-mail: [email protected] For information concerning IMPACT II opportunities, Adapter and Disseminator grants, please contact: The Education Fund 305-892-5099, Ext. 18 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.educationfund.org - 1 - INTRODUCTION Students are entertained and acquire knowledge through images; Internet, television, and films are examples. Though the printed word is essential in learning, educators have been taking notice of the new visual and oratory stimuli and incorporated them into classroom teaching. The purpose of this idea packet is to further introduce teacher colleagues to this methodology and share a compilation of films which may be easily implemented in secondary social studies instruction. Though this project focuses in grades 6-12 social studies we believe that media should be infused into all K-12 subject areas, from language arts, math, and foreign languages, to science, the arts, physical education, and more. In this day and age, students have become accustomed to acquiring knowledge through mediums such as television and movies. Though books and text are essential in learning, teachers should take notice of the new visual stimuli. Films are familiar in the everyday lives of students. -

The Representation of Suicide in the Cinema

The Representation of Suicide in the Cinema John Saddington Submitted for the degree of PhD University of York Department of Sociology September 2010 Abstract This study examines representations of suicide in film. Based upon original research cataloguing 350 films it considers the ways in which suicide is portrayed and considers this in relation to gender conventions and cinematic traditions. The thesis is split into two sections, one which considers wider themes relating to suicide and film and a second which considers a number of exemplary films. Part I discusses the wider literature associated with scholarly approaches to the study of both suicide and gender. This is followed by quantitative analysis of the representation of suicide in films, allowing important trends to be identified, especially in relation to gender, changes over time and the method of suicide. In Part II, themes identified within the literature review and the data are explored further in relation to detailed exemplary film analyses. Six films have been chosen: Le Feu Fol/et (1963), Leaving Las Vegas (1995), The Killers (1946 and 1964), The Hustler (1961) and The Virgin Suicides (1999). These films are considered in three chapters which exemplify different ways that suicide is constructed. Chapters 4 and 5 explore the two categories that I have developed to differentiate the reasons why film characters commit suicide. These are Melancholic Suicide, which focuses on a fundamentally "internal" and often iII understood motivation, for example depression or long term illness; and Occasioned Suicide, where there is an "external" motivation for which the narrative provides apparently intelligible explanations, for instance where a character is seen to be in danger or to be suffering from feelings of guilt. -

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS BEST FIRST SCREENPLAY 2012 NOMINEES (Winners in bold) *Will Reiser 50/50 BEST FEATURE (Award given to the producer(s)) Mike Cahill & Brit Marling Another Earth *The Artist Thomas Langmann J.C. Chandor Margin Call 50/50 Evan Goldberg, Ben Karlin, Seth Rogen Patrick DeWitt Terri Beginners Miranda de Pencier, Lars Knudsen, Phil Johnston Cedar Rapids Leslie Urdang, Dean Vanech, Jay Van Hoy Drive Michel Litvak, John Palermo, BEST FEMALE LEAD Marc Platt, Gigi Pritzker, Adam Siegel *Michelle Williams My Week with Marilyn Take Shelter Tyler Davidson, Sophia Lin Lauren Ambrose Think of Me The Descendants Jim Burke, Alexander Payne, Jim Taylor Rachael Harris Natural Selection Adepero Oduye Pariah BEST FIRST FEATURE (Award given to the director and producer) Elizabeth Olsen Martha Marcy May Marlene *Margin Call Director: J.C. Chandor Producers: Robert Ogden Barnum, BEST MALE LEAD Michael Benaroya, Neal Dodson, Joe Jenckes, Corey Moosa, Zachary Quinto *Jean Dujardin The Artist Another Earth Director: Mike Cahill Demián Bichir A Better Life Producers: Mike Cahill, Hunter Gray, Brit Marling, Ryan Gosling Drive Nicholas Shumaker Woody Harrelson Rampart In The Family Director: Patrick Wang Michael Shannon Take Shelter Producers: Robert Tonino, Andrew van den Houten, Patrick Wang BEST SUPPORTING FEMALE Martha Marcy May Marlene Director: Sean Durkin Producers: Antonio Campos, Patrick Cunningham, *Shailene Woodley The Descendants Chris Maybach, Josh Mond Jessica Chastain Take Shelter -

Movies About Writers & the Writing Life Compiled By

Movies About Writers & The Writing Life Compiled By Christina & Jason Katz Selection parameters: o A main character in the film must be a writer. No ensembles in this list unless writing is central to the storyline. o Only cinema movies are included. No TV movies. o Only print journalism. No broadcast journalism in this list. Screenwriting and TV writing are both represented. Bloggers are included. o Biographies or biopics about writers are listed. No documentaries are included. o No academics as central characters, unless the character is a novelist or some other type of writer. o Diaries are included, if the diary is part of the central part of the story. o Films are listed in chronological order by release year. o If a movie was re-released, then it is listed by its most recent release date. Thanks to everyone who contributed to this list. We had fun pulling it together. If you would like to refer the list to others, please send them to http://christinakatz.com/free/, where they can download the list in PDF form. Enjoy! 1. Barrets of Wimpole St. (1934) 2. It Happened One Night (1934) 3. His Girl Friday (1940) 4. The Philadelphia Story (1940) 5. Old Acquaintance (1943) 6. The Adventures of Mark Twain (1944) 7. The Lost Weekend (1945) 8. Christmas in Connecticut (1945) 9. I Remember Mama (1948) 10. The Third Man (1949) 11. In a Lonely Place (1950) 12. Sunset Boulevard (1950) 13. Orpheus (1950) 14. Hans Christian Andersen (1952) 15. A Face In The Crowd (1957) 16. Some Came Running (1958) 17. -

What Happened in Vegas?: the Use of Destination Branding to Influence Place Attachments

WHAT HAPPENED IN VEGAS?: THE USE OF DESTINATION BRANDING TO INFLUENCE PLACE ATTACHMENTS A Thesis by Kateri M. Grillot Bachelor of Fine Arts in Communication, Newman University, 2002 Submitted to the Department of the Elliott School of Communication and the faculty of the Graduate School of Wichita State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts May 2007 i © Copyright 2007 by Kateri M. Grillot All Rights Reserved i i WHAT HAPPENED IN VEGAS?: THE USE OF DESTINATION BRANDING TO INFLUENCE PLACE ATTACHMENTS I have examined the final copy of this thesis for form and content, and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts with a major in Communication. _________________________________ Susan Huxman, Committee Chair We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: _________________________________ Lisa Parcell, Committee Member _________________________________ Dorothy Billings, Committee Member ii i DEDICATION To my husband for believing, my family for supporting, and my son for inspiring iv You can tell the ideals of a nation by its advertisements. -Norman Douglas, 1917 v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Susan Huxman, for her guidance and enthusiasm. You embraced the project without knowing me and yet, you revealed unknown strengths in me. Thank you for your endless patience and support. Thanks are also due to my committee for investing time on this project and in me personally. I would like to thank Lisa Parcell, for her insight into public relations; your cheerful conversations were a delight and I will miss them. -

Cinema and Prostitution: How Prostitution Is Interpreted in Cinematographic Fiction

QUADERNS ISSN: 1138-9761 / www.cac.cat DEL CAC Cinema and prostitution: how prostitution is interpreted in cinematographic fiction JUANA GALLEGO Lecturer at the Communication Science Faculty of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona [email protected] Paper received 3 June 2010 and accepted 1 October 2010 Abstract Resum Prostitutes and prostitution have been widely represented in La qüestió de la prostitució i la figura de la prostituta han cinematographic narrative since the early days of cinema. estat un recurs àmpliament utilitzat en la ficció cinematogrà- Speaking about prostitution is a way of reflecting on human fica des dels inicis del cinema. Parlar de la prostitució és, sexuality and how this dimension of human life has evolved d’altra banda, reflexionar sobre la representació de la sexua- from the beginning of the 20th century until now. This article litat i l’evolució que ha experimentat aquesta dimensió de la is a summary of research currently underway into prostitution vida humana des de principis del segle XX fins a l’actualitat. in the cinema, analysing the figure of the prostitute in more Aquest article és un resum d’un treball de recerca en curs than 200 films, with a chapter that also tackles male prosti- sobre el sexe de pagament al cinema que analitza la figura de tution and their similarities and differences. la prostituta en més de 200 pel·lícules, amb un capítol en què també s’aborda la prostitució masculina i les similituds i Key words les diferències entre totes dues. Prostitution, cinema, sexuality, male prostitution. Paraules clau Prostitució, cine, sexualitat, prostitució masculina. -

Best Actor Oscar Winners Best Actress Oscar Winners Year Actor Age Movie Year Actress Age Movie 1980 Dustin Hoffman 42 Kramer Vs

Best Actor Oscar Winners Best Actress Oscar Winners Year Actor Age Movie Year Actress Age Movie 1980 Dustin Hoffman 42 Kramer vs. Kramer 1980 Sally Field 33 Norma Rae 1981 Robert De Niro 37 Raging Bull 1981 Sissy Spacek 31 Coal Miners Daughter 1982 Henry Fonda 76 On Golden Pond 1982 Katharine Hepburn 74 On Golden Pond 1983 Ben Kingsley 39 Gandhi 1983 Meryl Streep 33 Sophies Choice 1984 Robert Duvall 53 Tender Mercies 1984 Shirley MacLaine 49 Terms of Endearment 1985 F. Murray Abraham 45 Amadeus 1985 Sally Field 38 Places In The Heart 1986 William Hurt 36 Kiss of the Spider Woman 1986 Geraldine Page 61 The Trip to Bountiful 1987 Paul Newman 62 The Color of Money 1987 Marlee Matlin 21 Children Of A Lesser God 1988 Michael Douglas 43 Wall Street 1988 Cher 41 Moonstruck 1989 Dustin Hoffman 51 Rain Man 1989 Jodie Foster 26 The Accused 1990 Daniel Day-Lewis 32 My Left Foot 1990 Jessica Tandy 80 Driving Miss Daisy 1991 Jeremy Irons 42 Reversal of Fortune 1991 Kathy Bates 42 Misery 1992 Anthony Hopkins 54 The Silence of the Lambs 1992 Jodie Foster 29 The Silence of the Lambs 1993 Al Pacino 52 Scent of a Woman 1993 Emma Thompson 33 Howards End 1994 Tom Hanks 37 Philadelphia 1994 Holly Hunter 36 The Piano 1995 Tom Hanks 38 Forrest Gump 1995 Jessica Lange 45 Blue Sky 1996 Nicolas Cage 32 Leaving Las Vegas 1996 Susan Sarandon 49 Dead Man Walking 1997 Geoffrey Rush 45 Shine 1997 Frances McDormand 39 Fargo 1998 Jack Nicholson 60 As Good as It Gets 1998 Helen Hunt 34 As Good As It Gets 1999 Roberto Benigni 46 Life Is Beautiful 1999 Gwyneth Paltrow 26 -

Film Scr Ipts Online S Er

learn more at alexanderstreet.com S ONLINE FILM SCRIPTS ERIES From Here to Eternity Black Hawk Down The African Queen Fury Ben Hur Body Heat Mr. Deeds Goes to Town King Kong American Gigolo Double Indemnity Predator Suspicion Leaving Las Vegas His Girl Friday Trading Places Swing Time The Maltese Falcon Sunset Boulevard 2001: A Space Odyssey The Sting The Shining Urban Cowboy Platoon Billy Liar Unforgiven Broadcast News The Big Chill Comfort and Joy Blade Runner Pan’s Labyrinth Night of the Hunter The Jazz Singer State and Main Witness The Spanish Prisoner Tender Mercies Hotel Rwanda In the Line of Fire Rebel Without a Cause The Lavender Hill Mob Span’glish The Last Detail The Hustler Mr. Smith Goes to Washington Gods and Monsters Taxi Driver Mean Streets The Last Temptation of Christ Ararat Out of the Past Nashville The Magnificent Ambersons Film Scripts Online Series We watch, discuss, and analyze movies—but rarely do we read the scripts. While some well-known film scripts have appeared in print, most have never been published in any format. The scholar’s struggle to locate original scripts involves complicated permissions and negotiations, and holders of scripts are often reluctant to lend rare and unique documents. The Film Scripts Online Series makes Content available, for the first time, accurate and authorized versions of copyrighted The Film Scripts Online Series was recently screenplays. Now film scholars can expanded with Volume II to include 500 compare the writer’s vision with the new screenplays, along with monographs producer’s and director’s interpretations including the Film Classics series from from page to screen. -

Why Psychiatrists Should Watch Films (Or What Has Cinema Ever Done for Psychiatry?) Peter Byrne

Advances in psychiatric treatment (2009), vol. 15, 286–296 doi: 10.1192/apt.bp.107.005306 ARTICLE Why psychiatrists should watch films (or What has cinema ever done for psychiatry?) Peter Byrne Peter Byrne is a consultant me when some psychiatrists complain about their SUMMARY liaison psychiatrist and film studies unfavourable representations on film that cinema graduate. He devised and produced Cinema is at once a powerful medium, art, entertain has given psychiatry and psychiatrists a platform the short film1 in 4 (available at ment, an industry and an instrument of social www.rcpsych.ac.uk), which achieved they would not otherwise enjoy. Given the iron change; psychiatrists should neither ignore a UK cinema distribution in 2001. triangle of public anxiety and distrust of people nor censor it. Representations of psychiatrists His principal research interest is the with mental illness, an alienated tabloid press and stigma of mental health problems are mixed but psychiatric treatments are rarely and the effects of prejudice and portrayed posi tively. In this article, five rules of government policies focused on populist measures discrimination. He is Director of movie psychiatry are proposed, supported by (Cooper 2001), any media coverage that helps to Public Education for the Royal over 370 films. Commercial and artistic pressures engage that public is better than none. The worst College of Psychiatrists. reduce verisimilitude in fictional and factual films, response to ‘bad’ films would be a siege mentality/ Correspondence Dr Peter Byrne, Consultant Liaison Psychiatrist, although many are useful to advance understanding asylum culture among mental health professionals. Newham University Hospital, of phenomenology, shared history and social Would we and our patients really be better off if London E13 8SL, UK. -

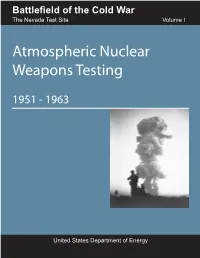

Atmospheric Nuclear Weapons Testing

Battlefi eld of the Cold War The Nevada Test Site Volume I Atmospheric Nuclear Weapons Testing 1951 - 1963 United States Department of Energy Of related interest: Origins of the Nevada Test Site by Terrence R. Fehner and F. G. Gosling The Manhattan Project: Making the Atomic Bomb * by F. G. Gosling The United States Department of Energy: A Summary History, 1977 – 1994 * by Terrence R. Fehner and Jack M. Holl * Copies available from the U.S. Department of Energy 1000 Independence Ave. S.W., Washington, DC 20585 Attention: Offi ce of History and Heritage Resources Telephone: 301-903-5431 DOE/MA-0003 Terrence R. Fehner & F. G. Gosling Offi ce of History and Heritage Resources Executive Secretariat Offi ce of Management Department of Energy September 2006 Battlefi eld of the Cold War The Nevada Test Site Volume I Atmospheric Nuclear Weapons Testing 1951-1963 Volume II Underground Nuclear Weapons Testing 1957-1992 (projected) These volumes are a joint project of the Offi ce of History and Heritage Resources and the National Nuclear Security Administration. Acknowledgements Atmospheric Nuclear Weapons Testing, Volume I of Battlefi eld of the Cold War: The Nevada Test Site, was written in conjunction with the opening of the Atomic Testing Museum in Las Vegas, Nevada. The museum with its state-of-the-art facility is the culmination of a unique cooperative effort among cross-governmental, community, and private sector partners. The initial impetus was provided by the Nevada Test Site Historical Foundation, a group primarily consisting of former U.S. Department of Energy and Nevada Test Site federal and contractor employees.