26 79 90 105 140 146 Niall Sharples*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dorset Places to Visit

Dorset Places to Visit What to See & Do in Dorset Cycling Cyclists will find the thousands of miles of winding hedge-lined lanes very enticing. Dorset offers the visitor a huge range of things to There is no better way to observe the life of the see and do within a relatively small area. What- countryside than on an ambling bike ride. The ever your interest, whether it be archaeology, more energetic cyclist will find a large variety of history, old churches and castles or nationally suggested routes in leaflets at the TICs. important formal gardens, it is here. Activities For people who prefer more organised Museums The county features a large number activities there is a wide range on offer, particu- of museums, from the world class Tank Museum larly in the vicinity of Poole, Bournemouth, to the tiniest specialist village heritage centre. All Christchurch and Weymouth. These cover are interesting and staffed by enthusiastic people everything expected of prime seaside resorts who love to tell the story of their museum. with things to do for every age and inclination. The National Trust maintains a variety of Coastline For many the prime attraction of properties here. These include Thomas Hardy’s Dorset is its coastline, with many superb beach- birthplace and his house in Dorchester. The es. Those at Poole, Bournemouth, Weymouth grandiose mansion of Kingston Lacy is the and Swanage have traditional seaside facilities creation of the Bankes family. Private man- and entertainments during the summer. People sions to visit include Athelhampton House and who prefer quiet coves or extensive beaches will Sherborne Castle. -

Abbotsbury & Inland

Itinerary #3 - Abbotsbury & Inland 16 15 Crown copyright 14 13 12 11 1 2 3 10 8 6 9 7 4 5 Abbotsbury lies at the centre West Bay to Portland. The size Abbotsbury & of a part of Dorset where the of the pebbles is graded from Inland visitor is spoilt for choice. The west to east, starting off with only answer is to keep coming pea-sized stones and gradual- 1. Chesil Beach 148 back for more. There are dra- ly increasing in diameter the 2. Burton Bradstock 148 matic views from everywhere further east one goes. There 3. Cogden Beach 148 along the B3167 coast road, is limited access to The Fleet 4. Abbotsbury 148 but one of the best vistas in lagoon except where the South Abbotsbury Castle 149 Dorset is undoubtedly from West Coast Path follows the Sub-Tropical Gardens 149 the steep hill west of the village. northern shore from Langton St Catherine’s Chapel 149 Swannery 148 Herring to Ferrybridge. 5. The Fleet 149 Stop in one of the several lay- 6. Hardy’s Monument 151 bies and take time to savour the The Ridgeway passes along 7. Hellstone 150 The Fleet and Chesil Beach, the Chalk spine which runs 8. The Valley of Stones 150 with Portland behind, St from Askerswell Down and on 9. The Mare & Her Colts 150 Catherine’s Chapel in the fore- to Purbeck. Large numbers of 10. Kingston Russell Circle 150 ground and Abbotsbury nest- prehistoric sites litter this area, 11. Nine Stones Circle 150 ling in its valley. -

Walking the Jurassic Coast Walking the Jurassic Coast

WALKING THE JURASSIC COAST WALKING THE JURASSIC COAST DORSET AND EAST DEVON: THE WALKS, THE ROCKS, THE FOSSILS By Ronald Turnbull JUNIPER HOUSE, MURLEY MOSS, OXENHOLME ROAD, KENDAL, CUMBRIA LA9 7RL www.cicerone.co.uk © Ronald Turnbull 2015 First edition 2015 CONTENTS ISBN: 978 1 85284 741 8 Reprinted 2017, 2019, 2021 (with updates) Map key ...................................................... 7 Printed in Singapore by KHL using responsibly sourced paper Strata diagram ................................................ 10 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Geological topic index .......................................... 12 This product includes mapping data licensed from Ordnance INTRODUCTION ............................................. 15 Survey® with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s The Jurassic Coast .............................................. 16 Stationery Office. © Crown copyright 2015 All rights reserved. When to walk ................................................. 17 Licence number PU100012932. Getting there and around ........................................ 17 Staying the night ............................................... 18 All photographs are by the author. Maps and GPS ................................................ 18 Safety at the seaside ............................................ 19 Using this guide ............................................... 20 GEOLOGICAL INTRODUCTION ................................. 21 The sea ..................................................... -

Dorset Building Stone Work Continues to Expand the Dorset Dorset Important Building Stone Website, Launched in Geological 2017

Dorset Environmental Records Centre Newsletter No.79 Spring/Summer 2018 ith the milder winters we have allows us to set different sensitivity For those of you looking for a new Wseen recently, the recording levels for different species. So for some challenge, I recently read an interesting season never really seems to stop but species like bats and badgers, DERC article by Douglas Boyes on some of it certainly gets a boost as the warmer will get the detailed data but on the the moths found in birds’ nests. Whilst weather comes in. Many of you are now distribution maps visible to all recorders, cleaning out the nest boxes in his using Living Record to collect data, the resolution can be set at 1 km or 10 Welsh garden Douglas took the disused and with over half a million records for km. At DERC, the list of ‘sensitive’ species nests and stored them in an unheated Dorset collected by Living Record since is relatively short. With guidance from outbuilding to see what emerged. He it started in 2010, it has made a huge the county recorders we have identified found four moth species including difference to the way we work. There are those species which may be at risk and set Niditinea striolella The Brindled Clothes other recording systems available, often our levels of access to data accordingly. Moth, a relatively scarce moth with a used for specific projects or recording However, not all systems have the same limited distribution. Douglas followed groups, like the BirdTrack apps local control levels. -

West Dorset Sites

DORSET AONB BUILT ENVIRONMENT ASSESSMENT: JOHN WYKES WEST DORSET SITES LCA22 BRIT VALLEY Location & landscape setting This area runs for 15kms from the sea, at West Bay, up the flood plain of the River Brit, through Bridport, to Netherbury and Beaminster. It is a contrasting corridor of developed coastline; reedy lower reaches of the river; the large town of Bridport (with distinctive green spaces along the river running into developed areas); an inland landscape of rounded hills; and Beaminster, attractively set in a bowl of higher hills, below Buckham Down and White Sheet Hill. The mature parkland of Parnham House abuts Beaminster on its southern edge and forms a fine entry into the town. Settlement form & pattern: The corridor contains the largest settlement in the area, Bridport, which grew as a route centre, market and industrial town (notably for rope, cordage and net production); it is nucleated around a former market place and shows evidence of a Saxon and medieval planned layout; West Bay developed from a small fishing hamlet to the port for Bridport and, from the late 19th-century, as a small pleasure resort; it is still nucleated around the Harbour but has spread north on the West Bay Road and up onto West Cliff; Pymore, to the north of Bridport, was a self- contained industrial complex, related to the processing of flax and the manufacturing of rope and net and is nucleated around its mill; Netherbury is a small, nucleated village at a minor route centre on a river crossing; Beaminster is a small market town, nucleated around its Square, again at a route centre of the main north- south road (A3066) and the east-west B3163 and several minor routes to the surrounding area; it has grown along several road ribbons but is constrained to the south by the proximity of Parnham House; DRAFT 1 DORSET AONB BUILT ENVIRONMENT ASSESSMENT: JOHN WYKES Edges of settlements are influenced by historical and physical factors. -

Licence Annex B

LICENCE ANNEX B: Summary of all restrictions relating to licensed actions on Sites of Special Scientific Interest, Special Areas of Conservation, Special Protection Areas and RAMSAR Sites within the county of Dorset Protected Sites that are within the assessment are not necessarily part of any active operations. Active operations can and will only occur on protected sites where landowner permission has been granted. SSSI Site Name European Site Licence Conditions Name (if applicable Abbotsbury Blind No additional conditions imposed Lane Abbotsbury Castle Restrict vehicles to existing tracks. Limit location of traps to existing sett footprint. Aunt Mary's West Dorset Alder Exclude SSSI or restrict vehicles to existing vehicular Bottom Woods SAC tracks & limit location of traps to within the sett footprint Axmouth to Lyme Sidmouth to West Exclude SSSI or restrict access to footpaths. Exclude Regis Under Cliffs Bay SAC the littoral sediment and supralittoral sediment and shingle zones. Limit location of traps to within sett footprint. Restrict vehicles to existing tracks. Purple Gromwell may be present on pathways... Babylon Hill No additional conditions imposed Batcombe Down Restrict vehicles to existing tracks. Limit location of traps to existing sett footprint or areas of scrub within Units 1, 3 and 4 Bere Stream Exclude SSSI or restrict vehicles to existing tracks. Limit location of traps to existing sett footprint. Limit location of traps to existing footprint or areas of scrub within Units 1 and 3. Black Hill Down Cerne & Sydling Restrict vehicles to existing tracks. Limit location of Downs SAC traps to existing footprint or areas of scrub. Exclude any Marsh Fritillary butterfly colony locations from vehicle movement or digging in of traps (likely to be on West or South facing slopes). -

Ed Board (PDF)

EXPLANATION OF THE PLATES. PLATES I., II. & III. Illustrate Dr. Buckland and Mr. De la Beche's paper on the Geology of the neighbour hood of Weymouth and the adjacent parts of the coast of Dorset. PLATE I. Geological Map of the neighbourhood of Weymouth and the adjacent parts of the coast of Dorset. The reader is requested to take notice that the authors do not profess to mark the exact limits of the lower Purbeck Beds in Portland, but merely to indicate their presence as the uppermost formation in the north end of that island. PLATE II. Series of Sections.—Colours the same as in the Map. Fig. 1. Section from the Great fault near Upway to the Bill of Portland*. Fig. 2. Section from the Great fault near Moigne's Down Farm to Ringstead Bay. Fig. 3. Section from the Great fault near Poxwell to the signal station near Osmington Mills. Fig. 4. Section from the Great fault near Sutton to the Sea at Ham Cliff. Fig. 5. Section from the Great fault near Sutton to Jordon Hill in Weymouth Bay. Fig. 6. Section from Abbotsbury Common over Linton Hill. Fig. 7. Section from Abbotsbury Castle to Abbotsbury Swanery, showing the continua tion of the Great fault. Fig. 8. Coast section from Jordon Hill to near Boat Cove. The apparent curvature in the Oxford Clay and other strata at the east end of this section arises from an inden tation of the coast: the strata have an E. and W. direction throughout, and dip rapidly N., and have not the bend here represented, by throwing the curves of the coast into a straight line. -

Programme 2: Frontline Dorset

Programme 2: Frontline Dorset In this week’s walk we cover a 60-mile stretch of the stunning coast of Dorset, uncovering evidence of a time when this sleepy county of rolling hills and winding lanes was utterly transformed. When WWII broke out and the threat of a Nazi invasion was real, Dorset was frontline Britain. This 5 day walk begins just outside the village of Abbotsbury, on the western edge of Chesil Beach. It heads through the harbours of Weymouth and Portland before taking in the spectacular landmark of Durdle Door. We watch our step as we cross the firing ranges of Lulworth,and make our way to Studland and Swanage; locations that played a vital role in the run-up to D-Day. Along the route we explore a rich history of the defiance and courage exhibited during the most destructive war the world has ever known. Please use OS Explorer Map: OL 15 Purbeck and South Dorset. All Distances approximate. Day 1 Abbotsbury to Weymouth, via Abbotsbury Anti-tank Defences, Abbotsbury Swannery and Langton Herring. Distance: 12.3 miles Day 2 Weymouth (via Portland) to Osmington Mills, via Nothe Fort, Portland, Jack Mantle’s Grave. Distance: 12.8 miles Day 3 Osmington Mills to Lulworth, via Ringstead Radar Bunker, Durdle Door and Lulworth Cove. Distance: 6.1 miles Day 4 Lulworth to Worth Matravers, via Lulworth Firing Ranges, Iron Age Hill Fort, St Aldhelm’s Head. Distance: 15.1 miles Day 5 Worth Matravers (via Studland Bay) to Swanage, via Fort Henry, Studland Bay. Distance: 14.3 miles Day 1: Abbotsbury to Weymouth, via Abbotsbury Anti-Tank Defences, Abbotsbury Swannery, Langton Herring. -

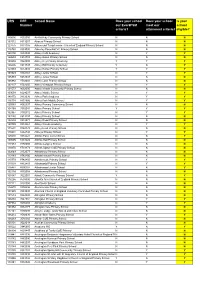

URN DFE Number School Name Does Your School Our Ever6fsm Criteria?

URN DFE School Name Does your school Does your school Is your Number our Ever6FSM meet our school criteria? attainment criteria? eligible? 140696 8552000 Ab Kettleby Community Primary School N N N 133312 8813257 Abacus Primary School N N N 123775 9333105 Abbas and Templecombe Church of England Primary School N N N 116780 8853000 Abberley Parochial VC Primary School N N N 140190 9283020 Abbey CofE Academy N Y Y 122659 8912788 Abbey Gates Primary School N N N 139404 3522000 Abbey Hey Primary Academy Y Y Y 136006 8913797 Abbey Hill Primary & Nursery Y N Y 123989 8612033 Abbey Hulton Primary School Y Y Y 103929 3332101 Abbey Junior School N Y Y 136989 8412647 Abbey Junior School N N N 106982 3732001 Abbey Lane Primary School N N N 132127 8732450 Abbey Meadows Primary School N Y Y 131573 8662000 Abbey Meads Community Primary School N N N 109654 8224037 Abbey Middle School N Y Y 140172 3812036 Abbey Park Academy N Y Y 116774 8852906 Abbey Park Middle School N Y Y 120063 8562337 Abbey Primary Community School N N N 104168 3352041 Abbey Primary School Y Y Y 102967 3192012 Abbey Primary School N Y Y 133280 8913297 Abbey Primary School N N N 122599 8912571 Abbey Road Primary School N N N 139709 9312461 Abbey Woods Academy N Y Y 115601 9162172 Abbeymead Primary School N N N 110401 8262348 Abbeys Primary School N Y Y 125580 9372421 Abbots Farm Junior School N N Y 139605 8833822 Abbots Hall Primary School N N N 117083 9192000 Abbots Langley School N N N 110850 8733373 Abbots Ripton CofE Primary School N N N 102649 3152077 Abbotsbury Primary School -

Heritage at Risk Register 2016, South West

South West Register 2016 HERITAGE AT RISK 2016 / SOUTH WEST Contents Heritage at Risk III Plymouth, City of (UA) 179 Poole (UA) 184 The Register VII Somerset 184 Content and criteria VII Exmoor (NP) 184 Criteria for inclusion on the Register IX Mendip 188 Sedgemoor 192 Reducing the risks XI South Somerset 196 Key statistics XIV Taunton Deane 202 Publications and guidance XV West Somerset 205 South Gloucestershire (UA) 206 Key to the entries XVII Swindon (UA) 208 Entries on the Register by local planning XIX authority Torbay (UA) 210 Bath and North East Somerset (UA) 1 Wiltshire (UA) 212 Bournemouth (UA) 3 Bristol, City of (UA) 4 Cornwall (UA) 8 Devon 46 Dartmoor (NP) 46 East Devon 73 Exeter 80 Exmoor (NP) 81 Mid Devon 82 North Devon 84 South Hams 89 Teignbridge 98 Torridge 101 West Devon 110 Dorset 113 Christchurch 113 East Dorset 114 North Dorset 119 Purbeck 126 West Dorset 134 Weymouth and Portland 152 Gloucestershire 153 Cheltenham 153 Cotswold 154 Forest of Dean 160 Gloucester 164 Stroud 166 Tewkesbury 169 Isles of Scilly (UA) 172 Isles of Scilly (UA) (off) 177 North Somerset (UA) 177 II South West Summary 2016 he South West has an exceptionally rich and diverse heritage, especially important for its prehistoric monuments such as Maiden Castle in Dorset, the largest Iron T Age hill fort in England. The region also played a key role in the nation’s industrial heritage leaving an important, but sometimes challenging legacy, from its iconic Cornish tin mines to its textile mills and Brunel’s engineering masterpieces for the Great Western Railway. -

Heritage at Risk Register 2018, South West

South West Register 2018 HERITAGE AT RISK 2018 / SOUTH WEST Contents The Register III Somerset 173 Content and criteria III Exmoor (NP) 173 Mendip 177 Criteria for inclusion on the Register V Sedgemoor 182 Reducing the risks VII South Somerset 186 Taunton Deane 191 Key statistics XI West Somerset 193 Publications and guidance XII South Gloucestershire (UA) 195 Key to the entries XIV Swindon (UA) 198 Entries on the Register by local planning XVI Torbay (UA) 200 authority Wiltshire (UA) 202 Bath and North East Somerset (UA) 1 Bournemouth (UA) 3 Bristol, City of (UA) 4 Cornwall (UA) 8 Devon 47 Dartmoor (NP) 47 East Devon 70 Exeter 77 Exmoor (NP) 78 Mid Devon 79 North Devon 82 South Hams 87 Teignbridge 94 Torridge 96 West Devon 105 Dorset 108 Christchurch 108 East Dorset 108 North Dorset 113 Purbeck 120 West Dorset 128 Weymouth and Portland 145 Gloucestershire 146 Cheltenham 146 Cotswold 146 Forest of Dean 151 Gloucester 154 Stroud 155 Tewkesbury 159 Isles of Scilly (UA) 162 North Somerset (UA) 167 Plymouth, City of (UA) 168 Poole (UA) 173 II HERITAGE AT RISK 2018 / SOUTH WEST LISTED BUILDINGS THE REGISTER Listing is the most commonly encountered type of statutory protection of heritage assets. A listed building Content and criteria (or structure) is one that has been granted protection as being of special architectural or historic interest. The LISTING older and rarer a building is, the more likely it is to be listed. Buildings less than 30 years old are listed only if Definition they are of very high quality and under threat. -

DORSET COUNTRYSIDE VOLUNTEERS ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING Held at West Stafford on July 3Rd 2010

Dorset Countryside Volunteers No 153 August - October 2010 Reg Charity No 1071723 www.dcv.org.uk Who we are, what we do, where, why and how . DCV is . A DCV day lasts . A practical conservation group run by volunteers 10.00a.m. – 5.00p.m. approximately since 1972 doing practical work in the Breaks for lunch and drinks countryside that would not otherwise be done Volunteers are male and female, from all walks FINDING DCV . of life, all ages and from all over the county Work is seasonal - in winter , woodland work, Maps with the task programme (at the back of this hedgelaying, coppicing; in summer dry stone newsletter) show the locations of task sites walling, clearing ponds, footpath work Look for DCV’s yellow arrows near the worksite or red and white tape or the DCV information board Organisations we work for include: Dorset may show an explanatory note Wildlife Trust (DWT), Heritage Coast Project, Natural England, National Trust, Amphibian & If unsure of the worksite try to arrive by 10.00 to Reptile Conservation Trust (ARC) meet other volunteers. The worksite may be some way off. Lost? give us a call on 07929 961532 We work at weekends throughout Dorset No super-human strength or special skills FOOD, DRINK & ACCOMMODATION needed, or attendance on every task or even for the whole weekend - any time is a bonus Occasionally, we hire a village hall, cook supper, visit the local pub and sleep overnight - karrimats DCV offers . available! N.B. Book with Peter a week in advance Practical care for the environment The charge for a weekend, including Saturday Opportunity to learn new skills - training given evening meal, lunch Saturday and Sunday, Use of all necessary tools breakfast on Sunday and accommodation, £3.00 DCV provides free hot/cold drinks and biscuits Beautiful countryside, social events, fun & companionship during the day - bring your own mug if you wish Link with a French conservation group On residentials, all volunteers are welcome to come for the evening meal and pub whether working both YOU should bring .