Crop Profile for Okra in Florida

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005

Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services U.S. Department of Agriculture www.healthierus.gov/dietaryguidelines i MESSAGE FROM THE SECRETARIES We are pleased to present the 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. This document is intended to be a primary source of dietary health information for policymakers, nutrition educators, and health providers. Based on the latest scientific evidence, the 2005 Dietary Guidelines provides information and advice for choosing a nutritious diet, maintaining a healthy weight, achieving adequate exercise, and “keeping foods safe” to avoid foodborne illness. This document is based on the recommendations put forward by the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. The Committee was composed of scientific experts who were responsible for reviewing and analyzing the most current dietary and nutritional information and incorporating this into a scientific evidence-based report. We want to thank them and the other public and private professionals who assisted in developing this document for their hard work and dedication. The more we learn about nutrition and exercise, the more we recognize their importance in everyday life. Children need a healthy diet for normal growth and development, and Americans of all ages may reduce their risk of chronic disease by adopting a nutritious diet and engaging in regular physical activity. However, putting this knowledge into practice is difficult. More than 90 million Americans are affected by chronic diseases and conditions that compromise their quality of life and well-being. Overweight and obesity, which are risk factors for diabetes and other chronic diseases, are more common than ever before. To correct this problem, many Americans must make significant changes in their eating habits and lifestyles. -

Physico-Chemical and Fatty Acid Composition of Oil Extracted by Acetone Solvent from Alligator Pepper (Aframomum Melegueta)

Chemistry Research Journal, 2017, 2(3):36-41 Available online www.chemrj.org ISSN: 2455-8990 Research Article CODEN(USA): CRJHA5 Physico-chemical and Fatty Acid Composition of Oil Extracted by Acetone Solvent from Alligator Pepper (Aframomum Melegueta) Aladekoyi Gbenga1, Ogundowle O1, Aladejimokun AO2, Adesuyi AT2, Alfred AO2 1Food Science and Technology Dept., Rufus Giwa Polytechnic, Owo, Ondo State, Nigeria 2Science Laboratory Technology Dept, Rufus Giwa Polytechnic, Owo, Ondo State, Nigeria Abstract To achieve a suitable concentration of the active ingredients contained in the plant or seed samples and that their action can be more effective, it is necessary to perform several procedures through which the active ingredients are extracted with the appropriate solvents, These are selected according to the solubility and stability of the beneficial substances. The acetone (a polar solvent) extracting method by soaking where adopted for the extraction of oil from alligator pepper seeds (Aframomum Melegueta) for adequate extraction. Since the water content easily soluble in acetone after decantation, a freeze drying method at -20 ℃ and vacuum pressure of 1.034 mBar was used to remove both the acetone and the water content. This prevented the effect of heat during drying on the essential oil present in the oil extracted from the sample. This method leaved the oil in its natural state for its Physico-chemical and fatty acid composition. The values obtained for the chemical composition were. Acid value (mg/KOH/g) 34.22±0.2, Iodine Value (wijs) 29.44±0.2, Saponification Value (Mg/KoH/g) 145.86±0.3 and Peroxide Value (mg/kg) 30.90±0.2 respectively, 1.4605±0.1 and 0.9034±0.1 were the values obtained for the physical parameters (Refractive Index and Specific gravity)respectively. -

Okra in the Garden Taunya Ernst and Dan Drost

March 2012 Horticulture/Vegetables/2012-02pr Okra in the Garden Taunya Ernst and Dan Drost Introduction Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) was introduced to America from Africa in the 1660s, likely as a result of the slave trade. Also known as gumbo, it is a warm season crop often grown in southern gardens where summers are hot and long. Okra is a member of the hibiscus family producing large yellow flowers, giving an ornamental appeal to many gardens. The immature pods are used in soups, stir fries, and stews, often as a thickening agent. Cultivars Okra varieties come in an assortment of heights, pod colors, sizes, and shapes. Plants grow from 12 inches to 6 feet tall with most cultivars reaching 3 to 6 feet high with a 2 to 4 foot spread. Plants produce pods 3 to 12 inches long and pods come in a range of colors (dark green to a whitish hue) and shapes (round, smooth or ridged). Annie Oakley II, a compact, hybrid cultivar, thrives in cool short season environments, making it better suited for a Utah garden. Other dwarf or early ripening varieties may be available. Consult your local nursery or garden center for other adapted varieties. in full sun and when temperatures are consistently Site Selection above 65 ˚F. Fertile, sandy loam soils with a pH of 6.0 to 7.0 are ideal for growing okra. Utah soils have a Soil Preparation higher pH (7.0 to 8.5) so it may be necessary to add Have the soil tested to determine nutrient sulfur or peat moss to modify pH levels. -

Okra Stewed in Tomato with Coriander and Preserved Lemon

Okra Stewed in Tomato with Coriander and Preserved Lemon Okra stewed in tomato with coriander and preserved lemon is one of my favorite dishes. I came across it inYotam Ottolenghi’s book Plenty and while I had previously cooked okra with tomato and spices, the particular flavours and the fact the okra is first roasted before being stewed really makes this version very special. Okra has a lot of fibre that becomes soluble on cooking, making it quite a slimy vegetable. While this is seen as an attribute for the thick gumbos of the Southern American states, the extreme unctiousness is not always sort out for dishes in other parts of the world, where the acidity of lemons or vinegar is used to lessen the effect. While I quite liked the sliminess it was not until I roasted the okra that I really came to adore this strange vegetable. Roasting is a great way to bring out the pleasant nutty flavours of vegetables such as cauliflower or Brussles sprouts while retarding the sulphur taste associated with these brassicas. Roasting also enhances the flavour of okra while keeping it toothsome and, you guessed it, not slimey. This dish is fragrant with coriander, preserved lemon and mint. While in Yotam’s version he adds whole coriander seeds in the tomato sauce, I prefer to scatter the seeds with the okra during roasting and use the finely minced roots and the leaves of a bunch of reshf coriander in the sauce instead. Some store bought brands of preserved lemon can have a rather artificial flavour for reasons I don’t quite know, so I now prefer to make use of my own which are nothing more than lemons and salt. -

The Gradual Loss of African Indigenous Vegetables in Tropical America: a Review

The Gradual Loss of African Indigenous Vegetables in Tropical America: A Review 1 ,2 INA VANDEBROEK AND ROBERT VOEKS* 1The New York Botanical Garden, Institute of Economic Botany, 2900 Southern Boulevard, The Bronx, NY 10458, USA 2Department of Geography & the Environment, California State University—Fullerton, 800 N. State College Blvd., Fullerton, CA 92832, USA *Corresponding author; e-mail: [email protected] Leaf vegetables and other edible greens are a crucial component of traditional diets in sub-Saharan Africa, used popularly in soups, sauces, and stews. In this review, we trace the trajectories of 12 prominent African indigenous vegetables (AIVs) in tropical America, in order to better understand the diffusion of their culinary and ethnobotanical uses by the African diaspora. The 12 AIVs were selected from African reference works and preliminary reports of their presence in the Americas. Given the importance of each of these vegetables in African diets, our working hypothesis was that the culinary traditions associated with these species would be continued in tropical America by Afro-descendant communities. However, a review of the historical and contemporary literature, and consultation with scholars, shows that the culinary uses of most of these vegetables have been gradually lost. Two noteworthy exceptions include okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) and callaloo (Amaranthus viridis), although the latter is not the species used in Africa and callaloo has only risen to prominence in Jamaica since the 1960s. Nine of the 12 AIVs found refuge in the African- derived religions Candomblé and Santería, where they remain ritually important. In speculating why these AIVs did not survive in the diets of the New World African diaspora, one has to contemplate the sociocultural, economic, and environmental forces that have shaped—and continue to shape—these foodways and cuisines since the Atlantic slave trade. -

A Review of the Literature

Pharmacogn J. 2019; 11(6)Suppl:1511-1525 A Multifaceted Journal in the field of Natural Products and Pharmacognosy Original Article www.phcogj.com Phytochemical and Pharmacological Support for the Traditional Uses of Zingiberacea Species in Suriname - A Review of the Literature Dennis RA Mans*, Meryll Djotaroeno, Priscilla Friperson, Jennifer Pawirodihardjo ABSTRACT The Zingiberacea or ginger family is a family of flowering plants comprising roughly 1,600 species of aromatic perennial herbs with creeping horizontal or tuberous rhizomes divided into about 50 genera. The Zingiberaceae are distributed throughout tropical Africa, Asia, and the Americas. Many members are economically important as spices, ornamentals, cosmetics, Dennis RA Mans*, Meryll traditional medicines, and/or ingredients of religious rituals. One of the most prominent Djotaroeno, Priscilla Friperson, characteristics of this plant family is the presence of essential oils in particularly the rhizomes Jennifer Pawirodihardjo but in some cases also the leaves and other parts of the plant. The essential oils are in general Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of made up of a variety of, among others, terpenoid and phenolic compounds with important Medical Sciences, Anton de Kom University of biological activities. The Republic of Suriname (South America) is well-known for its ethnic and Suriname, Paramaribo, SURINAME. cultural diversity as well as its extensive ethnopharmacological knowledge and unique plant Correspondence biodiversity. This paper first presents some general information on the Zingiberacea family, subsequently provides some background about Suriname and the Zingiberacea species in the Dennis RA Mans country, then extensively addresses the traditional uses of one representative of the seven Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Anton de Kom genera in the country and provides the phytochemical and pharmacological support for these University of Suriname, Kernkampweg 6, uses, and concludes with a critical appraisal of the medicinal values of these plants. -

Abelmoschus Esculentus) As a Potential Dietary Medicine with Nutraceutical Importance for Sustainable Health Applications

molecules Review Okra (Abelmoschus Esculentus) as a Potential Dietary Medicine with Nutraceutical Importance for Sustainable Health Applications Abd Elmoneim O. Elkhalifa 1 , Eyad Alshammari 1, Mohd Adnan 2 , Jerold C. Alcantara 3, Amir Mahgoub Awadelkareem 1, Nagat Elzein Eltoum 1, Khalid Mehmood 4, Bibhu Prasad Panda 5 and Syed Amir Ashraf 1,* 1 Department of Clinical Nutrition, College of Applied Medical Sciences, University of Hail, Hail 2440, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] (A.E.O.E.); [email protected] (E.A.); [email protected] (A.M.A.); [email protected] (N.E.E.) 2 Department of Biology, College of Science, University of Hail, Hail 2440, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] 3 Department of Clinical Laboratory Sciences, College of Applied Medical Sciences, University of Hail, Hail 2440, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] 4 Department of Pharmaceutics, College of Pharmacy, University of Hail, Hail 2440, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] 5 Microbial and Pharmaceutical Biotechnology Laboratory, Centre for Advanced Research and Pharmaceutical Sciences, School of Pharmaceutical Education and Research, Jamia Hamdard, New Delhi 110062, India; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +966-591-491-521 or +966-165-358-298 Citation: Elkhalifa, A.E.O.; Alshammari, E.; Adnan, M.; Alcantara, J.C.; Awadelkareem, A.M.; Abstract: Recently, there has been a paradigm shift from conventional therapies to relatively safer Eltoum, N.E.; Mehmood, K.; Panda, phytotherapies. This divergence is crucial for the management of various chronic diseases. Okra B.P.; Ashraf, S.A. Okra (Abelmoschus (Abelmoschus esculentus L.) is a popular vegetable crop with good nutritional significance, along Esculentus) as a Potential Dietary with certain therapeutic values, which makes it a potential candidate in the use of a variety of Medicine with Nutraceutical nutraceuticals. -

Pectin Isolation and Characterization from Six Okra Genotypes

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Huddersfield Repository 1 Pectin isolation and characterization from six okra genotypes 2 F. M. Kpodoa,b, J. K. Agbenorhevia, K. Albac, R. J. Binghamc, I. N. Oduroa , G. A. Morrisd and 3 V. Kontogiorgosc* 4 aDepartment of Food Science and Technology, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and 5 Technology, Kumasi, Ghana 6 bDepartment of Nutrition and Dietetics, University of Health and Allied Sciences, Ho, Ghana 7 cDepartment of Biological Sciences, University of Huddersfield, HD1 3DH, UK 8 d Department of Chemical Sciences, University of Huddersfield, HD1 3DH, UK 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 1 20 Abstract 21 Pectin was isolated by aqueous extraction at pH 6.0 from the pods of six different okra 22 genotypes (Abelmoschus esculentus L.). Genetic diversity was determined using fragment length 23 analysis (FLA) of ten simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers. Physical and chemical evaluation 24 of pectin was performed by means of FT-IR and NMR spectroscopy, sugar composition analysis 25 (GC-MS), size exclusion chromatography coupled to multi-angle laser light scattering (SEC- 26 MALLS), dilute solution viscometry and steady shear rheology assisted by principal component 27 analysis (PCA). Each of the SSR markers detected on average 4.1 alleles and revealed unique 28 genotypes for each sample. Extraction yield was between 11–14 % resulting in pectin with 29 galacturonic acid content between 43–63 %, low degree of methyl-esterification (17–25 %) and 30 high degree of acetylation (20–40 %). -

World Rural Observations 2013;5(3) Http

World Rural Observations 2013;5(3) http://www.sciencepub.net/rural Repellance Effect Of Aqueous Extract Of Alligator Pepper (Aframomum Melegueta K. Schum) On Insects Of Okra Okpako E.C., Osuagwu A.N., Agbor R.B., Ekpo I.A., Kalu S.E Department of Genetics and Biotechnology, University of Calabar, Calabar, Nigeria E-mail: [email protected]; Phone No. 08063430125 ABSTRACT: Food security could be achieved through the use of bio-insecticide to prevent insect attacks on crops which invariably would have cause damage to the crops, thereby resulting in poor crop production. The repellence effect of aqueous extract of Alligator pepper (Aframomum melegueta K. Schum) on the growth and yield of okra was investigated. The aqueous seed extract was prepared by air drying the spices material (A. melegueta) after drying, the seeds were pulverized to powder. Ten percent (10%) aqueous extract was prepared by soaking 100g of the spice powder in one liter of distilled water and allowed for 24 hours. Different concentrations of the extract were prepared consisting of control (0%), 2.5%, 5.0%, and 10%. The treatment was applied twice a week. Data were collected based on the following parameters. Days to 50% seedling emergence, plant height, number of leaves, leaf area, days to 50% flowering, pod length, number of pods, and number of seeds. The result showed that there were no significant difference (P>0.05) in the days to seedling emergence, days to flowering, pod length, number of pods and number of seeds but significant difference (P<0.05) was observed on the plant height, leaf area and number of leaves per plant. -

Effect of Variety and Plant Density on Growth and Yield of Okra (Abelmoschus Esculentus (L.) Moench)

IOSR Journal of Agriculture and Veterinary Science (IOSR-JAVS) e-ISSN: 2319-2380, p-ISSN: 2319-2372. Volume 9, Issue 2 Ver. II (Feb. 2016), PP 38-42 www.iosrjournals.org Effect of Variety and Plant Density on Growth and Yield of Okra (Abelmoschus Esculentus (L.) Moench) Aliyu, U.1, Ajala, A. A1. 1Department of Crop Science, Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto,Nigeria Abstract: Field trials were conducted at the Fruit and Vegetable Teaching and Research Farm, Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto during the 2013 and 2014 raining seasons, to study the effects of variety and plant population density (in terms of intra-row spacing) on the growth and yield of okra (Abelmoschus esculentus (L.) Moench). The treatments consisted of three plant population densities, 50,000 plants per ha, 66,666 plants per ha and 100,000 plants per ha by varying the intra row spacing at 40cm, 30cm and 20cm respectively and two varieties of okra, namely Dogo(Local variety) and Clemson spineless (improved variety) which were laid out in a Randomized Complete Block Design (RCBD) and replicated three times. The results obtained revealed that variety had significant influence on the growth and yield of okra. Dogo variety was higher in terms of plant height at 5 and 8 weeks after planting whereas Clemson spineless variety was higher in terms of number of branches per plant at 2 and 8 weeks after planting, pod weight, pod length, number of pods per plant and pod yield per hectare. Intra-row spacing of 40cm recorded more number of branches per plant at 5 weeks after planting. -

Type of Okra (Abelmoschus)And Its Nature of Resistance to Yellow Vein Mosaic Virus Disease

Cytologia 51: 753-756, 1986 Origin of 'Guineen' Type of Okra (Abelmoschus)and its Nature of Resistance to Yellow Vein Mosaic Virus Disease K. J. Madhusoodanan and M. A. Nazeer Indian Cardamom ResearchInstitute, Kailasanadu-685553, Kerala, India and Rubber Research Institute of India, Kottayam-686009, Kerala, India AcceptedJuly 27, 1985 The tender green fruit of okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) is prominent among the warmer region vegetables. In India, the high suceptibility of the plant to yellow vein mosaic disease spread by an insect vector Bemisia tabaci Genn. leads at times to a loss of about 94% of the crop (Shastry and Singh 1974), besides the fruit is also attacked by borer (Earias insulana). Hybridization with a 'Guineen' type of okra, an yellow vein mosaic resistant and pest immune species, followed by back-crossing and selection has already been taken up to incorporate the disease resistant genes while tenabling the palatability of A. esculentus fruit. For the success of such a rational crossing programme, a thorough understanding of the cytogenetic relation ships between the two types would be an indispensable prerequisite. It is also im portant from the phylogenetic stand-point. Materials and methods The 'Guineen' type (Fig. 1) used in the present study is an accession of okra introduced by the Division of Plant Introduction, I.A. R.I., New Delhi from Ghana which was initially considered as Abelmoschusmanihot but not confirmedas it closely resembles A. esculentusas well. The other one-'Soudanien' type (A. esculentus(L.) Moench; Fig. 2) is a race cultivated locally. The type names are as proposed by Siemonsma (1982). -

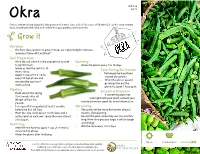

Okra Diam Nonummy Nibh Lorem Ipsum Dolor Sit Amet, Lorem Ipsum Okra Is a Warm-Season Vegetable That Grows Well in Most Texas Soils

EHT-158 Kids can help too! 04/21 Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetuer adipiscing elit, sed Okra diam nonummy nibh Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, Lorem ipsum Okra is a warm-season vegetable that grows well in most Texas soils. A fair source of Vitamindolor A, sitit can Lorem be eatenipsum in sit many Cucumberways, including boiled, fried, and cooked in soups, gumbos, and casseroles. amet, consectetuer, sed GrowGrow itit Subheader CUCUMBER Varieties • The best okra varieties to grow in Texas are ‘Cajun Delight,’ ‘Clemson Spineless,’ ‘Emerald,’ ‘Lee Dwarf.’ Soil Preparation • Work the soil when it is dry enough not to stick Watering to garden tools. • Water the plants every 7 to 10 days. Subheader• Spade or turn the soil 8 to 10 inches deep. Care During the Season • Pull weeds by hand from • Apply ½ cup of 15-5-10 for around okra plants. every 10 feet of row and • When the okra is up and mix into the top 3 to 4 growing, thin out the inches of soil. plants to about 1 foot apart. Planting • Plant okra in the spring Insects & Diseases • If something does not 2 to 3 weeks after all look rightSubheader with your plant, contact your danger of frost has county Extension agent for more information. passed. • For a good fall crop, plant at least 3 months Harvesting before the first fall frost. • Okra pods will be ready for harvest about 2 Subheader• Plant the okra seeds about 1 inch deep and 2 Subheadermonths after planting. inches apart in each row. Space the rows at least • Harvest the pods when they are 3 to 4 inches 3 feet apart.