Ritual Vessel (Ding) [Chinese]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inscriptional Records of the Western Zhou

INSCRIPTIONAL RECORDS OF THE WESTERN ZHOU Robert Eno Fall 2012 Note to Readers The translations in these pages cannot be considered scholarly. They were originally prepared in early 1988, under stringent time pressures, specifically for teaching use that term. Although I modified them sporadically between that time and 2012, my final year of teaching, their purpose as course materials, used in a week-long classroom exercise for undergraduate students in an early China history survey, did not warrant the type of robust academic apparatus that a scholarly edition would have required. Since no broad anthology of translations of bronze inscriptions was generally available, I have, since the late 1990s, made updated versions of this resource available online for use by teachers and students generally. As freely available materials, they may still be of use. However, as specialists have been aware all along, there are many imperfections in these translations, and I want to make sure that readers are aware that there is now a scholarly alternative, published last month: A Source Book of Ancient Chinese Bronze Inscriptions, edited by Constance Cook and Paul Goldin (Berkeley: Society for the Study of Early China, 2016). The “Source Book” includes translations of over one hundred inscriptions, prepared by ten contributors. I have chosen not to revise the materials here in light of this new resource, even in the case of a few items in the “Source Book” that were contributed by me, because a piecemeal revision seemed unhelpful, and I am now too distant from research on Western Zhou bronzes to undertake a more extensive one. -

Maria Khayutina • [email protected] the Tombs

Maria Khayutina [email protected] The Tombs of Peng State and Related Questions Paper for the Chicago Bronze Workshop, November 3-7, 2010 (, 1.1.) () The discovery of the Western Zhou period’s Peng State in Heng River Valley in the south of Shanxi Province represents one of the most fascinating archaeological events of the last decade. Ruled by a lineage of Kui (Gui ) surname, Peng, supposedly, was founded by descendants of a group that, to a certain degree, retained autonomy from the Huaxia cultural and political community, dominated by lineages of Zi , Ji and Jiang surnames. Considering Peng’s location right to the south of one of the major Ji states, Jin , and quite close to the eastern residence of Zhou kings, Chengzhou , its case can be very instructive with regard to the construction of the geo-political and cultural space in Early China during the Western Zhou period. Although the publication of the full excavations’ report may take years, some preliminary observations can be made already now based on simplified archaeological reports about the tombs of Peng ruler Cheng and his spouse née Ji of Bi . In the present paper, I briefly introduce the tombs inventory and the inscriptions on the bronzes, and then proceed to discuss the following questions: - How the tombs M1 and M2 at Hengbei can be dated? - What does the equipment of the Hengbei tombs suggest about the cultural roots of Peng? - What can be observed about Peng’s relations to the Gui people and to other Kui/Gui- surnamed lineages? 1. General Information The cemetery of Peng state has been discovered near Hengbei village (Hengshui town, Jiang County, Shanxi ). -

Piece Mold, Lost Wax & Composite Casting Techniques of The

Piece Mold, Lost Wax & Composite Casting Techniques of the Chinese Bronze Age Behzad Bavarian and Lisa Reiner Dept. of MSEM College of Engineering and Computer Science September 2006 Table of Contents Abstract Approximate timeline 1 Introduction 2 Bronze Transition from Clay 4 Elemental Analysis of Bronze Alloys 4 Melting Temperature 7 Casting Methods 8 Casting Molds 14 Casting Flaws 21 Lost Wax Method 25 Sanxingdui 28 Environmental Effects on Surface Appearance 32 Conclusion 35 References 36 China can claim a history rich in over 5,000 years of artistic, philosophical and political advancement. As well, it is birthplace to one of the world's oldest and most complex civilizations. By 1100 BC, a high level of artistic and technical skill in bronze casting had been achieved by the Chinese. Bronze artifacts initially were copies of clay objects, but soon evolved into shapes invoking bronze material characteristics. Essentially, the bronze alloys represented in the copper-tin-lead ternary diagram are not easily hot or cold worked and are difficult to shape by hammering, the most common techniques used by the ancient Europeans and Middle Easterners. This did not deter the Chinese, however, for they had demonstrated technical proficiency with hard, thin walled ceramics by the end of the Neolithic period and were able to use these skills to develop a most unusual casting method called the piece mold process. Advances in ceramic technology played an influential role in the progress of Chinese bronze casting where the piece mold process was more of a technological extension than a distinct innovation. Certainly, the long and specialized experience in handling clay was required to form the delicate inscriptions, to properly fit the molds together and to prevent them from cracking during the pour. -

Deciphering China's AI Dream

1 | Deciphering China’s AI Dream Deciphering China’s AI Dream The context, components, capabilities, and consequences of China’s strategy to lead the world in AI Jeffrey Ding* Centre for the Governance of AI, Future of Humanity Institute, University of Oxford March 2018 *Address correspondence to [email protected]. For comments and input, I thank: Miles Brundage, Allan Dafoe, Eric Drexler, Sophie-Charlotte Fisher, Carrick Flynn, Ben Garfinkel, Jimmy Goodrich, Chelsea Guo, Elsa Kania, Jade Leung, Jared Milfred, Luke Muehlhauser, Brian Tse, Helen Toner, and Baobao Zhang. A special thanks goes to Danit Gal for feedback that inspired me to rewrite significant portions of the report, Roxanne Heston for her generous help in improving the structure of the report, and Laura Pomarius for formatting and production assistance. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 INTRODUCTION 7 I. CONTEXT 7 A. China’s AI expectations vs. current scale of AI industry 8 B. China’s AI ambitions vs. other countries’ AI strategies 11 II. COMPONENTS 14 A. Key consistencies and differences with other science and technology plans 14 B. Channels from these key features to drivers of AI development 16 III. CAPABILITIES 23 A. Evaluation of China’s current AI capacities by driver 23 i. Catch-up approach in hardware 23 ii. Closed critical mass of data 25 iii. Algorithm development is high-quality but still lacking in fundamental innovation 25 iv. Partnership with the private AI sector 27 B. Assessment of China’s position on the AI Potential Index 28 IV. CONSEQUENCES 30 A. Emerging engagement in AI ethics and safety 30 B. -

Summary Life in the Shang Dynasty Shang Rulers and Gods Top 10

Summary Life in the Shang Dynasty Map showing the expanse of the Shang Dynasty Shang society was divided into different classes. At the top Did you know? were the royal family, and then priests and administrative Warriors were able to join The Shang Dynasty, also known as the Yin between 1523 and 1028 BCE. THE UPPER classes. Members of the aristocracy were well-respected, and the upper classes. The CLASSES more successful they were Dynasty, ruled the Yellow River Valley in the had clothes made from the finest materials. They were often in battle, the higher they second millenium BCE (approx 1675-1046BCE). given the responsibility of governing small areas. could rise! Life was very different for peasants, who were at the bottom Did you know? The Shang Dynasty succeeded the Xia Dynasty of the social ladder. The majority of the population was in this THE LOWER Peasants were governed and was followed by the Zhou Dynasty. bracket were limited to farming crops and selling handmade by local aristocrats, and CLASSES had little hope of leaving items for a profit. Some lower classes were buried with their masters, leading archaeologists to believe they were slaves. their life of peasantry. It was the first Chinese Dynasty for which there is Shang people ate a varied diet! The basic food was millet, a Did you know? written and archaeological evidence. type of grain, but barley and wheat were also grown. Shang The people of the Shang FOOD farmers were also skilled, growing vegetables and beans. Fish Dynasty also kept domesticated animals, The Dynasty expanded its territory and moved were caught in the rivers, and some animals (for example deer such as pigs, dogs, goats its capital city on several occasions. -

The Legacy of Bronzes and Bronze Inscriptions in Early Chinese Literature Paul R

The Legacy of Bronzes and Bronze Inscriptions in Early Chinese Literature Paul R. Goldin [DRAFT —not for citation] The most famous references to bronze inscriptions in early Chinese literature are probably the “written on bamboo and silk” passages in the Mozi 墨子 (which furnished the title for a highly regarded study of Chinese codicology by Chicago’s own Tsuen- hsuin Tsien 錢存訓). 1 More than once, when asked to justify a consequential but historically questionable statement, Mozi is said to have responded: “It is written on bamboo and silk; it is inscribed in bronze and stone; it is incised on platters and bowls; and [thus] it is transmitted to the sons and grandsons of later generations” 書於竹帛,鏤 於金石,琢於槃盂,傳遺後世子孫.2 But in asserting that such documents convey credible information about the activities of the ancestors, Mohists were—as in so many other matters 3—atypical of their intellectual culture. The more common ancient attitude toward the testimony of inscriptions was one of gentle skepticism: inscriptions were regarded as works of reverent commemoration, and incorporating the whole truth within them was taken to be as indecorous as, say, portraying Louis XIV complete with his gout and fistulas. As we read in an undated ritual text, “Protocols of Sacrifice” (“Jitong” 祭 統), currently found in the compendium Ritual Records ( Liji 禮記): 夫鼎有銘,銘者,自名也。自名以稱揚其先祖之美,而明著之 後世者也。為先祖者,莫不有美焉,莫不有惡焉,銘之義,稱美而不 稱惡,此孝子孝孫之心也。唯賢者能之。 銘者,論譔其先祖之有德善,功烈勳勞慶賞聲名列於天下,而 1 Written on Bamboo and Silk: The Beginnings of Chinese Books and Inscriptions , ed. Edward L. Shaughnessy, 2nd edition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004). -

Chinese Bronzes from the Meiyintang Collection Volume 2 Christian

Chinese Bronzes from the Meiyintang Collection Volume 2 Christian Deydier Chinese Bronzes from the Meiyintang Collection Volume 2 Chinese Bronzes from the Meiyintang Collection Volume 2 Christian Deydier Contents 9 Foreword 11 Chronology 13 Map 14 Studies of archaic Chinese bronze ritual vessels 24 Casting techniques 28 Fake bronzes 36 Shapes Catalogue 57 I - Xia / Erlitou culture 73 II - Early Shang / Erligang period 103 III - Late Shang / Yinxu period 151 IV - Western Zhou dynasty 187 V - Early Eastern Zhou / Spring and Autumn period 203 VI - Late Eastern Zhou / Warring States period 217 VII - Han dynasty 220 Bibliography 6 7 Since the publication of Volume 1 of Chinese Bronzes in the Meiyintang Collection, the collection has expanded and fifty more ritual bronzes have been added to those which have already been published. Many of the new acquisitions take us back to the very origins of bronze- vessel casting in China or, in other words, to the Erlitou cultural period (19th – 16th centuries BC.) in the Xia dynasty and the Erligang period (16th – 14th centuries BC.) at the beginning of the Shang dynasty. As a result of the collector’s recently renewed concentration on these early periods, the Meiyintang Collection has been able to acquire several exceptional bronzes of the Erlitou period, such as the extremely rare jiao listed as no. 160 (p. 68) and has also, as a result, now become the most complete collection in private hands of bronze ritual vessels of the Erligang period. The archaic bronze vessels in the Meiyintang Collection, probably the most important private collection of its type in terms of the quality, the rarity and the impeccable provenances of its objects, are a concrete testament to and a visual reminder of the primary importance in Chinese culture of the ancestral cult. -

Not for Citation Reflections on Literary and Devotional Aspects of Western

Draft – Not for Citation Reflections on Literary and Devotional Aspects of Western Zhou Memorial Inscriptions Robert Eno 伊若泊 Symposium on Ancient Chinese Bronzes, University of Chicago, 2010 This essay poses some very general questions concerning Western Zhou bronze inscriptions as a corpus that seem to me problems that are of intrinsic interest, inspired by one vessel in particular in the Shouyang Studio collection, and mixing a few other recently recovered inscriptions with ones I’m more familiar with in reflecting on the issues I want to raise. I should begin with a confession that it has been some years since I dealt with bronze inscriptions as part of a research agenda, and I cannot claim close familiarity with a wide range of those that have come to light in recent years, though working on this paper has helped me to know better what it is that I do not know. I have titled it a reflection because it is not the fruit of extensive and ongoing research, but my hope is that it raises issues of interest that are also ones we have the tools to explore. The issues that concern me here are these: First, given the highly formulaic and restricted nature of most bronze texts, and the fact that significant portions of many seem to be redactions of texts originally created on other materials, wood or bamboo, how far can we identify in these texts elements of literary creativity and what might be construed as personal expression arising from the occasion of creating memorial inscriptions in bronze? Second, acknowledging that the context for the -

Major Vessel Types by Use

Major Vessel Types by Use Vessel Use Food Wine Water xian you you Vessel Type ding fang ding li or yan gui yu dou fu jue jia he gu zun lei hu (type 1) (type 2) fang yi pan Development Stage Pottery Prototype Early Shang (approx 1600–1400 BCE) Late Shang (approx 1400–1050 BCE) Western Zhou (approx 1050–771 BCE) Eastern Zhou (approx 770–256 BCE) PLEASE DO NOT REMOVE FROM THE GALLERY Shang Ceremony What was a ceremony at the Shang court like? thrust, now into a matching hollow on the left side David Keightley in his Sources of Shang History of the shell: ‘It is due to Father Jia.’ More time provides a wonderful description of what such passes . another crack forms in response. Moving a ceremony might have entailed. to the next plastron, Chue repeats the charges: ‘It is not due to Father Jia.’ Puk. ‘It is due to Father Jia.’ “Filtering through the portal of the ancestral temple, He rams the brand into the hollows and cracks the the sunlight wakens the eyes of the monster mask, second turtle shell, then the third, then the fourth. bulging with life on the garish bronze tripod. At the center of the temple stands the king, at the center “The diviners consult. The congregation of kinsmen of the four quarters, the center of the Shang world. strains to catch their words, for the curse of a dead Ripening millet glimpsed though the doorway father may, in the king’s eyes, be the work of a Shang-dynasty ritual wine vessel (he), Shang-dynasty ritual wine vessel (jue), shows his harvest rituals have found favor. -

The 9Th East China Partial Differential Equations Conference & Shanxi

The 9th East China Partial Differential Equations Conference & Shanxi International Conference on Partial Differential Equations (First Announcement) Shanxi University, Taiyuan, Shanxi, China July 16{19, 2012 Aim of the conference: The 9th East China Partial Differential Equations Conference & Shanxi International Conference on Partial Differential Equations, is to be held at Taiyuan, Shanxi, China, from July 16th to July 19th of 2012. This conference is jointly organized by the School of Mathematical Sciences of Shanxi University (Shanxi, Taiyuan), the Department of Mathematics and the Center for PDE of East China Normal University (Shanghai). It is our goal to increase the academic exchanges and interactions in PDE research in China, and also to showcase the state of art in PDE research to the young researchers especially in Shanxi. Registration: If you plan to participate this conference, please send us an e-mail by June 1st, 2012 to the organizing committee via email [email protected] and containing your name, affiliation, postal address, e-mail address, travel schedule and additional information and comments. Deadline: The deadline for registration is June 1st, 2012. Titles and abstracts of all the invited talks/contributed talks must be received by June 1st, 2012. Abstracts should be typed in LaTeX or plain text document, containing your name, institute affiliation, postal address, e-mail address, title and abstract, not to exceed 200 words and sent by email to [email protected]. Conference Schedule: July 15 (Sunday): Arrival -

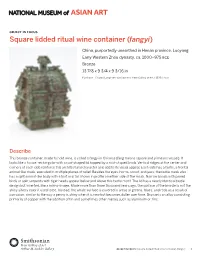

Object in Focus: Square Lidded Ritual Wine Container (Fangyi)

object in focus Square lidded ritual wine container (fangyi) China, purportedly unearthed in Henan province, Luoyang Early Western Zhou dynasty, ca. 1000–975 BCE Bronze 13 7/8 x 9 3/4 x 9 3/16 in Purchase—Charles Lang Freer Endowment. Freer Gallery of Art, F1930.54a-b Describe This bronze container, made to hold wine, is called a fangyi in Chinese (fang means square and yi means vessel). It looks like a house: rectangular with a roof-shaped lid topped by a roof-shaped knob. Vertical ridges at the center and corners of each side reinforce this architectural character and add to its visual appeal. Each side has a taotie, a frontal animal-like mask, executed in multiple planes of relief. Besides the eyes, horns, snout, and jaws, the taotie mask also has a split animal-like body with a foot and tail shown in profle on either side of the mask. Narrow bands with paired birds or split serpents with tiger heads appear below and above this taotie motif. The lid has a nearly identical taotie design but inverted, like a mirror-image. Made more than three thousand years ago, the surface of the bronze is not the shiny silvery color it used to be. Instead, the whole surface is covered in areas of greens, blues, and reds as a result of corrosion, similar to the way a penny is shiny when it is new but becomes duller over time. Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper with the addition of tin and sometimes other metals such as aluminum or zinc. -

English Language, Large Print

ENGLISH LANGUAGE, LARGE PRINT Ancient Bells RESOUND of China Resound: Ancient Bells of China Bells were among the first metal objects created in China. Beginning over 3,500 years ago, small, primitive noisemakers grew into gongs and further evolved into sets of hand bells for playing melodies. Centuries of technological experimentation later resulted in sophisticated bells that produced two pitches when struck at different spots. Variations in size, shape, decoration, and sound also reveal regional differences across north and south China. By the late Bronze Age large sets of tuned bells were played in ensemble performances in both areas. Cast from bronze, these durable instruments preserve valuable hints about the character of early Chinese music. Today we can use technology to explore these ancient bells and to explain their acoustical properties, but we know little about the actual sound of this early music. To bring the bells to life, we commissioned three composers to create soundscapes using the recorded tones of a 2,500‐ year‐old bell set on display. Each of them also produced a video projection to interpret his composition with moving images that allow us to "see sound." Unless otherwise indicated, all of these objects are from China, are made of bronze, and were the gift of the Dr. Paul Singer Collection of Chinese Art of the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; a joint gift of the Arthur M. Sackler Foundation, Paul Singer, the AMS Foundation for the Arts, Sciences, and Humanities, and the Children of Arthur M. Sackler. 2 Symbols of Refinement Chinese regional courts competed with one another on the battlefield and on the music stage.