Centre for Reproductive Rights and Other

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Programming for Justice: Access for All

Programming for Justice: Access for All A Practitioner’s Guide to a Human Rights-Based Approach to Access to Justice Photo Credit: 1.Woman in Dolakha, UNDP Nepal, 2003 2. UNICEF East Asia and Pacific Regional Office, UNICEF/EAP00067/UNKNOWN 3. Local Mediation Council (Salish) Meeting, Munira Morshed Munni/UNDP Bangladesh, 2002 Copyright@2005 United Nations Development Programme Asia-Pacific Rights and Justice Intiative UNDP Regional Centre in Bangkok UN Service Building Rajdamnern Nok Avenue Bangkok 10200 Thailand ISBN: 974-93210-5-7 FOREWORD The Hon Justice Michael Kirby AC CMG* I like this book. It aims to help officials, aid agencies, civil society organizations and judges and lawyers to fulfil the true purposes of law. The book has grown out of the fine objectives of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). I honour UNDP and the officers who work within it. Truly, they participate in an agency that takes seriously the fundamental purposes of the United Nations organization,declared in the Charter. From the start,the United Nations has been founded on the tripartite principles of attaining peace and security; upholding human rights and fundamental freedoms;and promoting economic equity and justice. The subjects of this book are important for the promotion of these objectives. Attaining them is essential to building a better, safer and more equitable world. I have seen UNDP at work in the post-conflict situation in Cambodia; in the changeover to multi-party democracy in Malawi; and in a myriad of programmes in many other lands. The people of the world thirst for real justice and not just words and shibboleths. -

Alternative Report by Civil Society To

Nepal's Civil Society ALTERNATIVE REPORT to the UN Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination in addition to the Government of Nepal periodic reports 17 to 23, to be reviewed at the 95th session, 23 April -11 May 2018 Caste-Based Discrimination and Untouchability against Dalit in Nepal February 2018 Prepared by: Dalit NGO Federation Nepal SAMATA Foundation Nepal National Dalit Social Welfare Organization Feminist Dalit Organization Jagaran Media Center Rastriya Dalit Network, Madeshi Dalit Bikash Mahasangh In association with: Human Rights Treaty Monitoring Coordination Committee International Dalit Solidarity Network Key contact: Dalit NGO Federation Nepal Lalitpur Metropolitan City Ward No.22 Mitra Road Galli No. 6, Chakupat, Lalitpur. Email: [email protected] Tel: +977-01-5261219 URL: www.dnfnepal.org 1 Table of Contents Abbreviations .................................................................................................................................. 3 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 4 2. Discrimination against Dalits in Nepal ....................................................................................... 6 3. Updates on the previous CERD recommendations ..................................................................... 7 Article 1: Definitions of racial discrimination ............................................................................ 8 Article 2: Measures to eliminate -

Promoting Gender Equality and Social Inclusion: Nepal’S Commitments and Obligations

PROMOTING GENDER EQUALITY AND SOCIAL INCLUSION: NEPAL’S COMMITMENTS AND OBLIGATIONS PROMOTING GENDER EQUALITY AND SOCIAL INCLUSION: NEPAL’S COMMITMENTS AND OBLIGATIONS Publisher INHURED International Post Box No: 12684, Kathmandu Kupondole, Lalitpur Ph: 5010536, Fax: 5010616 Email: [email protected] www.inhuredinternational.org PROMOTING GENDER EQUALITY AND SOCIAL INCLUSION: NEPAL’S COMMITMENTS AND OBLIGATIONS I Editing : Ms. Shreejana Pokhrel Gopal Krishna Siwakoti, PhD Research team : Advocate Rita Mainaly Advocate Salina Kafle Advocate SushmaThapa Ms. Salina Joshi Preparatory team : Ms. Kripa Basnyat Ms. Sushila Limbu Ms. Akriti Gautam Special Contribution : Ms. Nandita Baruah Ms. Kripa Basnyat Ms. Sumitra Manandhar Ms. Tirza Theunissen Cover Photo : Conor-Ashleigh ISBN : 978-9937-8387-9-5 Design & Print : Creative Press Pvt. Ltd. Kathmandu, Nepal Copyright : INHURED International DISCLAIMER: This “Promoting Gender Equality and Social Inclusion: Nepal’s Commitments and Obligations” has been made possible by the support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and The Asia Foundation (TAF). The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of INHURED International and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government and TAF. II PROMOTING GENDER EQUALITY AND SOCIAL INCLUSION: NEPAL’S COMMITMENTS AND OBLIGATIONS ACKNOWLEDGEMENT International Institute for Human Rights Environment and Development (INHURED International) implemented “Promoting -

Diagnostic Study of Local Governance in Federal Nepal 2017

Diagnostic Study of Local Governance in Federal Nepal 2017 Diagnostic Study of Local Governance in Federal Nepal 2017 The Diagnostic Study of Local Governance in Federal Nepal was implemented with support from the Australian Government-The Asia Foundation Partnership on Subnational Governance in Nepal. The findings and any views expressed in this study do not reflect the views of the Australian Government or that of The Asia Foundation. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Diagnostic Study of Local Governance in Federal Nepal was implemented through the Australian Government, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) – The Asia Foundation Partnership on Subnational Governance in Nepal. The study was produced under the guidance of The Foundation Program Director, Bishnu Adhikari with support and inputs from Program Officer, Srijana Nepal. The study fieldwork and initial analysis was provided by a team of Nepal Centre for Contemporary Studies led by Dr. Krishna Hachhethu. The final publication was drafted with the assistance of consultant Asha Ghosh and intern Iain Payne. The Partnership is profoundly grateful to the locally elected representatives and people of Nepal who took the time to participate in this study and share their views. TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................. 1 1.1 THE PROMISED PATH OF FEDERALISM ......................................................... 1 1.2 FRAMEWORK FOR THE FUTURE ....................................................................... 3 -

Download Publication

RESEARCH REPORT Emerging Issues of Confict in November 2019 Federalized Context in Nepal 1 EMERGING ISSUES OF CONFLICT IN FEDERALIZED NEPAL Research Report November 2019 ASIAN ACADEMY FOR PEACE RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT Emerging Issues of Conflict in Federalized Context in Nepal November 2019 1000 Copies ASIAN ACADEMY Copyright : © FOR PEACE RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT ISBN : 978-9937-0-6973-1 Research Advisors : Mr. Shiva K Dhungana Mr. Tulasi R Nepal Reacher Team : Leader – Rabindra Bhattarai Member – Rita Bhadra Shrestha Member – Sharad Chandra Neupane Publisher : Asian Academy for Peace, Research and Development Thapagaun, Baneshwor, Kathmandu Email: [email protected] Tel: 015244060 i FOREWORD The research ‘Emerging Issues of Conflict in Federalized Context in Nepal’ has aimed at identifying the issues related to the implementation of the federal restructuring in the country. The research is an outcome of the desk review and field level interviews and focus group discussions in nine districts namely Ilam, Jhapa, Morang, Dhanusha, Mahottari, Makawanpur, Surkhet, Kailali and Rukum West, as well as drawings from a national level interaction held in Kathmandu to disseminate and validate the findings from the field. Asian Academy for Peace, Research and Development (Asian Peace Academy) expresses its sincere gratitude to Kurve Wustrow, Centre for Training and Networking in Non-violence Actions and Civil Society Platform for Peacebuilding and Statebuilding (CSPPS) for their support to undertake this research. A team of researchers collected and analysed the information to draw findings of the study. Therefore, the research is a collaborative effort of the researchers and field level supporting hands. I would like to thank Mr. -

Nepal's Constitution of 2015

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:40 constituteproject.org Nepal's Constitution of 2015 Unofficial translation by Nepal Law Society, International IDEA, and UNDP. This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:40 Table of contents Preamble . 12 PART 1: Preliminary . 12 1. Constitution as the fundamental law . 12 2. Sovereignty and state authority . 12 3. Nation . 13 4. State of Nepal . 13 5. National interest . 13 6. Language of the nation . 13 7. Language of official transaction . 13 8. National flag . 14 9. National anthem, etc. 14 Part 2: Citizenship . 14 10. Not to be denied of citizenship . 14 11. To be deemed citizen of Nepal . 14 12. Citizenship based on descent and gender identity . 15 13. Acquisition, re-acquisition and termination of citizenship . 15 14. Non-resident Nepali citizenship may be granted . 16 15. Other provisions related to citizenship of Nepal . 16 PART 3: Fundamental Rights and Duties . 16 16. Right to live with dignity . 16 17. Right to Freedom . 16 18. Right to equality . 18 19. Right to communication . 18 20. Right to Justice . 19 21. Right of victim of crime . 20 22. Right against torture . 20 23. Right against preventive detention . 20 24. Right against untouchability and discrimination . 21 25. Right to property . 21 26. Right to religious freedom . 22 27. Right to information . 22 28. Right to privacy . 22 29. Right against exploitation . 22 30. Right regarding clean environment . 23 31. Right to education . -

A Reading Guide to Nepalese History

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 25 Number 1 Himalaya No. 1 & 2 Article 5 2005 A Reading Guide to Nepalese History John Whelpton Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Whelpton, John. 2005. A Reading Guide to Nepalese History. HIMALAYA 25(1). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol25/iss1/5 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. jOHN WHELPTON A READING GUIDE TO NEPAL ESE HISTORY ·t.t. ' There is no single book or series that can be regarded as · an authoritative Chandra Shamsher and Family history of Nepal in the way that, This brief survey is intended as a list of works which Scientifique in France. This can be consulted online at for example, I have found especially useful myself or which I http://www.vjf.cnrs.fr/wwwisis/BIBLI0.02/form.htm the Cambridge think would be particularly suitable for readers wanting to follow up topics necessarily treated very · Ancient History BASIC NARRATIVES cursorily in my recent one-volume History of Nepal ' or the Oxford (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005). It There is no single book or series that can be regarded History of England includes some of the pre-1990 works listed in my as an authoritative history of Nepal in the way that, is accepted in the earlier Nepal (World Bibliographical Series, Oxford for example, the Cambridge Ancient History or the & Santa Barbara: Clio Press, 1990) and, though it Oxford History of England is accepted in the United United Kingdom. -

Of the Indigenous Peoples of Nepal

Alternative Report of the Indigenous Peoples of Nepal to the Sate Report Submitted by the Government of Nepal to the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination Submitted to 95th Session of the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) Palais des Nations CH-1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland Submitted by Lawyers' Association for Human Rights of Nepalese Indigenous Peoples (LAHURNIP) Nepal Federation of Indigenous Nationalities (NEFIN) National Indigenous Women's Federation (NIWF) Youth Federation of Indigenous Nationalities (YFIN) Nepal Indigenous Disabled Association (NIDA) National Coalition Against Racial Discrimination (NCARD) Indigenous Women's Legal Awareness Group (INWOLAG) Kathmandu, Nepal March 2018 1 PART I INTRODUCTION, SCOPE AND METHODOLOGY Introduction 1. Nepal is a "multiethnic, multi-lingual, multi-religious, multi-cultural and diverse regional characteristics"1 country. The country is the homeland to 125 caste/ethnic groups, 123 languages and 10 religious groups.2 The total population of Nepal is 26,494,504.3 Among them, indigenous peoples (IPs) comprise 35.8 percent of the total population. Nepal has legally recognized 59 indigenous nationalities, referred to as Adivasi Janajati. The country has entered into a new State structure with promulgation of new Constitution in September 2015. IPs of Nepal were forcibly assimilated in third category of Hindu Caste hierarchical system, that was legally institutionalized with the codification of the Civil Code (Muluki Ain) 1854. Further the Act divided IPs into slaveable and enslaveable. The Civil Court is still in practice with some changes. The principles and the notion of the Civil Code reflected in several existing legal provisions. -

DEMOCRACY in ACTION Annual Outcome Report 2019

INTERNATIONAL IDEA Supporting democracy worldwide DEMOCRACY IN ACTION Annual Outcome Report 2019 www.idea.int @Int_IDEA InternationalIDEA DEMOCRACY IN ACTION Annual Outcome Report 2019 Graphic design: Vision Communication ISBN: 978-91-7671-304-4 DOI: https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2020.12 International IDEA SE–103 34 Stockholm © 2020 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance SWEDEN +46 8 698 37 00 International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political [email protected] interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the www.idea.int views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council of Member States. 2 Annual Outcome Report 2019 International IDEA 3 Annual Outcome Report 2019 Contents Reclaiming democracy’s promise................................................................................................................1 Mentoring elected local officials in Nepal .........................................................................................42 Letter from the Secretary-General .....................................................................................................1 International IDEA looks to regional governance in Bolivia to bolster development .............................44 Introduction .....................................................................................................................................2 Training for increased women's political participation in Myanmar ...................................................46 -

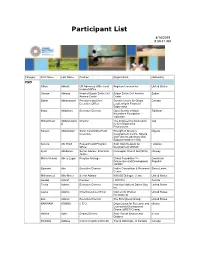

Participant List

Participant List 4/14/2019 8:59:41 AM Category First Name Last Name Position Organization Nationality CSO Jillian Abballe UN Advocacy Officer and Anglican Communion United States Head of Office Osman Abbass Head of Sudan Sickle Cell Sudan Sickle Cell Anemia Sudan Anemia Center Center Babak Abbaszadeh President and Chief Toronto Centre for Global Canada Executive Officer Leadership in Financial Supervision Ilhom Abdulloev Executive Director Open Society Institute Tajikistan Assistance Foundation - Tajikistan Mohammed Abdulmawjoo Director The Engineering Association Iraq d for Development & Environment Kassim Abdulsalam Zonal Coordinator/Field Strength in Diversity Nigeria Executive Development Centre, Nigeria and Farmers Advocacy and Support Initiative in Nig Serena Abi Khalil Research and Program Arab NGO Network for Lebanon Officer Development (ANND) Kjetil Abildsnes Senior Adviser, Economic Norwegian Church Aid (NCA) Norway Justice Maria Victoria Abreu Lugar Program Manager Global Foundation for Dominican Democracy and Development Republic (GFDD) Edmond Abu Executive Director Native Consortium & Research Sierra Leone Center Mohammed Abu-Nimer Senior Advisor KAICIID Dialogue Centre United States Aouadi Achraf Founder I WATCH Tunisia Terica Adams Executive Director Hamilton National Dance Day United States Inc. Laurel Adams Chief Executive Officer Women for Women United States International Zoë Adams Executive Director The Strongheart Group United States BAKINAM ADAMU C E O Organization for Research and Ghana Community Development Ghana -

Nepali Politics and the Rise of Jang Bahudur Rana, 1830

NEPALI POLITICS AND THE RISE OF JANG BAHUDUR RANA, 1830-1857 John Whelpton Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London February 1987 ProQuest Number: 10673006 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673006 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 ABSTRACT The thesis examines the political history of Nepal from 1830, covering the decline and fall of Bhimsen Thapa, the factional struggles $ which ended with Jang Bahadur Kunwar (later Rana)'s emergence as premier in 1846, and Jang1s final securing of his own position when he assumed the joint roles of prime minister and maharaja in 1857. The relationship between king, political elite (bharadar'i) , army and peasantry is analysed, with special prominence given to the religious aspects of Hindu kingship, and also to the role of prominent Chetri families and of the Brahman Mishras, Pandes and Paudyals who provided the rajgurus (royal preceptors). -

Reflections on Contemporary Nepal

Deepak Thapa Deepak THE POLITICS OF This companion volume to A Survey of the Nepali People in 2017 has been designed to provide insights into CHANGE the general socio-political context in CHANGE which the survey was conducted. The contributors provide perspectives on Contributors a range of topics to highlight issues Nandita Baruah pertinent to the changes Nepal Yurendra Basnett has experienced in recent years, Jonathan Goodhand particularly since the adoption of Krishna Khanal the new constitution in 2015 and Sameer Khatiwada the 2017 elections. These include THE POLITICS OF Dhruba Kumar politics at the national and local Sanjaya Mahato levels; women in politics; identity Bimala Rai Paudyal and inclusion; the dynamics in Janak Rai borderland areas; and the challenges Chandan Sapkota facing the Nepali economy. The six Sara Shneiderman articles in this book are expected to Oliver Walton make a significant contribution to the literature on the early years of CHANGE federal Nepal. Reflections on Contemporary Nepal edited by 9789937 597531 Deepak Thapa THE POLITICS OF CHANGE THE POLITICS OF CHANGE Reflections on Contemporary Nepal edited by Deepak Thapa The production of this volume was supported through the Australian Government–The Asia Foundation Partnership on Subnational Governance in Nepal. Any views expressed herein do not reflect the views of the Australian Government or those of The Asia Foundation. © Social Science Baha and The Asia Foundation, 2019 ISBN 978 9937 597 53 1 Published by Himal Books for Social Science Baha and The Asia Foundation. Social Science Baha 345 Ramchandra Marg, Battisputali Kathmandu – 9, Nepal Tel: +977-1-4472807 www.soscbaha.org The Asia Foundation 1722 Thirbam Sadak Kathmandu, Nepal www.asiafoundation.org Himal Books Himal Kitab Pvt Ltd 521 Narayan Gopal Sadak, Lazimpat Kathmandu – 2 www.himalbooks.com Printed in Nepal Contents Foreword vii Introduction ix Deepak Thapa 1.