Variation in Avian Diversity in Relation to Plant Species in Urban Parks of Aydin, Turkey - 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal Editorial Staff: Rachel Cobb, David Pfaff, Patricia Riley Hammer, Henri Nier, Suzanne Pierot, Sabina Sulgrove, Russell Windle

Spring 2010 Volume 36 IVY J OURNAL IVY OF THE YEAR 2011 Hedera helix ‘Ivalace’ General Information Press Information American Ivy Society [email protected] P. O. Box 163 Deerfield, NJ 08313 Ivy Identification, Registration Membership Russell A. Windle The American Ivy Society Membership American Ivy Society Laurie Perper P.O. Box 461 512 Waterford Road Lionville, PA 19353-0461 Silver Spring, MD, 20901 [email protected] Officers and Directors President—Suzanne Warner Pierot Treasurer—Susan Hendley Membership—Laurie Perper Registrar, Ivy Research Center Director—Russell Windle Taxonomist—Dr. Sabina Mueller Sulgrove Rosa Capps, Rachel Cobb, Susan Cummings, Barbara Furlong, Patricia Riley Hammer, Constance L. Meck, Dorothy Rouse, Daphne Pfaff, Pearl Wong Ivy Journal Editorial Staff: Rachel Cobb, David Pfaff, Patricia Riley Hammer, Henri Nier, Suzanne Pierot, Sabina Sulgrove, Russell Windle The Ivy Journal is published once per year by the American Ivy Society, a nonprofit educational organization. Membership includes a new ivy plant each year, subscription to the Ivy Journal and Between the Vines, the newsletter of The American Ivy Society. Editorial submissions are welcome. Mail typed, double-spaced manuscript to the Ivy Journal Editor, The American Ivy Society. Enclose a self-addressed, stamped envelope if you wish manuscript and/ or artwork to be returned. Manuscripts will be handled with reasonable care. However, AIS assumes no responsibility for safety of artwork, photographs, or manuscripts. Every precaution is taken to ensure accuracy but AIS cannot accept responsibility for the corrections or accuracy of the information supplied herein or for any opinion expressed. The American Ivy Society P. O. Box 163, Deerfield Street, NJ 08313 www.ivy.org Remember to send AIS your new address. -

PACKAGE LEAFLET Package Leaflet: Information for the Patient

PACKAGE LEAFLET Package leaflet: Information for the patient Pulmocap Hedera, stroop Dry extract of ivy leaf Read all of this leaflet carefully before you start taking this medicine because it contains important information for you. Always take this medicine exactly as described in this leaflet or as your doctor or pharmacist have told you. - Keep this leaflet. You may need to read it again. - Ask your pharmacist if you need more information or advice. - If you get any side effects, talk to your doctor or pharmacist. This includes any possible side effects not listed in this leaflet. See section 4. - You must talk to a doctor if you do not feel better or if you feel worse after 5 days. What is in this leaflet 1. What Pulmocap Hedera is and what it is used for 2. What you need to know before you take Pulmocap Hedera 3. How to take Pulmocap Hedera 4. Possible side effects 5. How to store Pulmocap Hedera 6. Contents of the pack and other information 1. What Pulmocap Hedera is and what it is used for Pulmocap Hedera is a herbal medicinal product used as an expectorant in case of productive cough. It contains the dry extract of ivy leaf (Hedera helix L., folium). Pulmocap Hedera is indicated in adults, adolescents and children older than 2 years. You must talk to a doctor if you do not feel better or if you feel worse after 5 days. 2. What you need to know before you take Pulmocap Hedera Do not use this medicine: - if you are allergic to ivy, other members of the Araliaceae family or any other ingredients of this medicine (listed in section 6). -

Proper Listing of Scientific and Common Plant Names In

PROPER USAGE OF PLANT NAMES IN PUBLICATIONS A Guide for Writers and Editors Kathy Musial, Huntington Botanical Gardens, August 2017 Scientific names (also known as “Latin names”, “botanical names”) A unit of biological classification is called a “taxon” (plural, “taxa”). This is defined as a taxonomic group of any rank, e.g. genus, species, subspecies, variety. To allow scientists and others to clearly communicate with each other, taxa have names consisting of Latin words. These words may be derived from languages other than Latin, in which case they are referred to as “latinized”. A species name consists of two words: the genus name followed by a second name (called the specific epithet) unique to that species; e.g. Hedera helix. Once the name has been mentioned in text, the genus name may be abbreviated in any immediately subsequent listings of the same species, or other species of the same genus, e.g. Hedera helix, H. canariensis. The first letter of the genus name is always upper case and the first letter of the specific epithet is always lower case. Latin genus and species names should always be italicized when they appear in text that is in roman type; conversely, these Latin names should be in roman type when they appear in italicized text. Names of suprageneric taxa (above the genus level, e.g. families, Asteraceae, etc.), are never italicized when they appear in roman text. The first letter of these names is always upper case. Subspecific taxa (subspecies, variety, forma) have a third epithet that is always separated from the specific epithet by the rank designation “var.”, “ssp.” or “subsp.”, or “forma” (sometimes abbreviated as “f.”); e.g. -

Hedera Helix Information Guide

New York City EcoFlora Hedera helix L. English Ivy Araliaceae (Aralia family) Description: Evergreen woody vine, young shoots and inflorescences covered with stellate hairs or peltate scales; juvenile stems creeping and forming extensive mats, the mature stems up to 25 centimeters diameter, climbing by abundant, adventitious roots with adhesive pads. Leaves simple, alternate, dimorphic, 4–10 cm long; juvenile leaves palmately lobed with 3 or 5 triangular lobes, glabrous, the base cordate, the apex acute or acuminate, the upper surface shining and dark green with whitened veins, sometimes tinged purple in winter, the lower surface pale green; mature leaves ovate or rhombic, entire, otherwise like juveniles. Flowers in axillary umbels; sepals 5, very short; petals 5, fleshy, green; stamens 5; ovary inferior. Fruit a drupe with 2–3 pyrennes, turning black at maturity. Where Found: Hedera helix is native to Europe from Ireland and Norway to the Caucasus. In New York City, the species is most abundant near home sites and gardens where there is a history of cultivation, especially in suburban areas. Natural History: In its native Europe, bees and other insects obtain nectar from the flowers and birds disperse the fruit. The adventitious climbing roots secrete an adhesive polymer composed of nanoparticles. Root hairs shrink and curl as they dry, pulling the stem closer to the surface. These forces enable the plant to climb very high and accumulate great mass. When a tree is so encumbered, its photosynthetic potential is diminished and the tree is vulnerable to breakage in wind and ice storms. The ground covering impedes absorption from rainfall and creates desert-like conditions dominated by one species. -

Hedera: a Public Hashgraph Network & Governing Council

Hedera: A Public Hashgraph Network & Governing Council The trust layer of the internet Dr. Leemon Baird, Mance Harmon, and Paul Madsen WHITEPAPER V.2.1 LAST UPDATED AUGUST 15, 2020 SUBJECT TO FURTHER REVIEW & UPDATE 1 Vision To build a trusted, secure, and empowered digital future for all. Mission We are dedicated to building a trusted and secure online world that empowers you. Where you can work, play, buy, sell, create, and engage socially. Where you have safety and privacy in your digital communities. Where you are confident when interacting with others. Where this digital future is available to all. Hello future. © 2018-2020 Hedera Hashgraph, LLC. All rights reserved. WHITEPAPER 2 Executive Summary Distributed ledger technologies (DLT) have the potential to disrupt and transform existing markets in multiple industries. However, in our opinion there are five fundamental obstacles to overcome before distributed ledgers can be widely accepted and adopted by enterprises. In this paper we will examine these obstacles and discuss why Hedera Hashgraph is well-suited to support a vast array of applications and become the world’s first mass-adopted public distributed ledger. 1. PERFORMANCE - The most compelling use cases for DLT require hundreds of thousands of transactions per second, and many require consensus latency measured in seconds. These performance metrics are orders of magnitude beyond what current public DLT platforms can achieve. 2. SECURITY - If public DLT platforms are to facilitate the transfer of trillions of dollars of value, they will be targeted by hackers, and so will need the strongest possible network security. Having the strongest possible security starts with the consensus algorithm itself, with its security properties formally proven mathematically. -

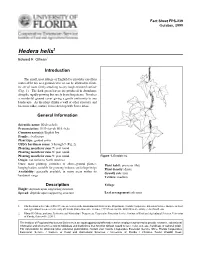

Hedera Helix1

Fact Sheet FPS-239 October, 1999 Hedera helix1 Edward F. Gilman2 Introduction The small, neat foliage of English Ivy provides excellent material for use as a ground cover or can be allowed to climb, its aerial roots firmly attaching to any rough-textured surface (Fig. 1). The dark green leaves are produced in abundance along the rapidly growing but rarely branching stems. It makes a wonderful ground cover giving a gentle uniformity to any landscape. As the plant climbs a wall or other structure and becomes older, mature leaves develop with fewer lobes. General Information Scientific name: Hedera helix Pronunciation: HED-dur-uh HEL-licks Common name(s): English Ivy Family: Araliaceae Plant type: ground cover USDA hardiness zones: 5 through 9 (Fig. 2) Planting month for zone 7: year round Planting month for zone 8: year round Planting month for zone 9: year round Figure 1. English Ivy. Origin: not native to North America Uses: mass planting; container or above-ground planter; Plant habit: prostrate (flat) hanging basket; suitable for growing indoors; cut foliage/twigs Plant density: dense Availablity: generally available in many areas within its Growth rate: fast hardiness range Texture: medium Description Foliage Height: depends upon supporting structure Spread: depends upon supporting structure Leaf arrangement: alternate 1.This document is Fact Sheet FPS-239, one of a series of the Environmental Horticulture Department, Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida. Publication date: October, 1999 Please visit the EDIS Web site at http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu. 2. Edward F. Gilman, professor, Environmental Horticulture Department, Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida, Gainesville, 32611. -

FSC Nettlecombe Court Nature Review 2014

FSC Nettlecombe Court Nature Review 2014 Compiled by: Sam Tuddenham Nettlecombe Court- Nature Review 2014 Introduction The purpose of this report is to review and share the number of different species that are present in the grounds of Nettlecombe Court. A significant proportion of this data has been generated by FSC course tutors and course attendees studying at Nettlecombe court on a variety of courses. Some of the data has been collected for the primary purpose of species monitoring for nationwide conservation charities e.g. The Big Butterfly Count and Bee Walk Survey Scheme. Other species have just been noted by members or staff when out in the grounds. These records are as accurate as possible however we accept that there may be species missing. Nettlecombe Court Nettlecombe Court Field Centre of the Field Studies Council sits just inside the eastern border of Exmoor national park, North-West of Taunton (Map 1). The house grid reference is 51o07’52.23”N, 32o05’8.65”W and this report only documents wildlife within the grounds of the house (see Map 2). The estate is around 60 hectares and there is a large variety of environment types: Dry semi- improved neutral grassland, bare ground, woodland (large, small, man –made and natural), bracken dominated hills, ornamental shrubs (lawns/ domestic gardens) and streams. These will all provide different habitats, enabling the rich diversity of wildlife found at Nettlecombe Court. Nettlecombe court has possessed a meteorological station for a number of years and so a summary of “MET” data has been included in this report. -

Toxicodendron Radicans) in the Free-Air Tyree

February 2008 COMMENTS 585 Sotala, D. J., and C. M. Kirkpatrick. 1973. Foods of white- Schnitzer et al. (2008) contrast results from a recent tailed deer, Odocoileus virginianus,inMartinCounty, experimental study documenting increased growth of Indiana. American Midland Naturalist 89:281–286. Sperry, J. S., N. M. Holbrook, M. H. Zimmerman, and M. T. poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans) in the free-air Tyree. 1987. Spring filling of xylem vessels in wild grapevine. carbon dioxide enrichment (FACE) facility in the Duke Plant Physiology 83:414–417. Forest, North Carolina (Mohan et al. 2006), to an Stiles, E. W. 1982. Fruit flags: two hypotheses. American uncontrolled observational study finding decreased Naturalist 120:500–509. Walters, M. B., and P. B. Reich. 2000. Seed size, nitrogen abundance of poison ivy in Wisconsin forests between supply and growth rate affect tree seedling survival in deep 1959 and 2005 (Londre´and Schnitzer 2006). Schnitzer et shade. Ecology 81:1887–1901. al. (2008) accurately point out that controlled field Ward, J. K., and J. Kelly. 2004. Scaling up evolutionary studies may not always emulate long-term responses in responses to elevated CO2: lessons from Arabidopsis. Ecology Letters 7:427–440. uncontrolled ‘‘real world’’ forests. The lack-of-change in WDNR (Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources). 2004. overall vine abundance in the Wisconsin forests is in Southern forest communities. Ecological landscapes of contrast to previous studies showing recent increases in Wisconsin—Ecosystem Management Planning Handbook, the abundance of vines in temperate (Myster and Pickett HB1805.1. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Madison, Wisconsin, USA. 1992, Dillenburg et al. -

Habitat Use and Space Preferences of Eurasian Bullfinches (Pyrrhula Pyrrhula) in Northwestern Iberia Throughout the Year

Hernández Avian Res (2021) 12:8 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40657-021-00241-0 Avian Research RESEARCH Open Access Habitat use and space preferences of Eurasian Bullfnches (Pyrrhula pyrrhula) in northwestern Iberia throughout the year Ángel Hernández1,2* Abstract Background: For all vertebrates in general, a concerted efort to move beyond single season research is vital to improve our understanding of species ecology. Knowledge of habitat use and selection by Eurasian Bullfnches (Pyrrhula pyrrhula) is limited with regard to the non-breeding season. To date, research on the habitat of the Iberian subspecies iberiae consists of very general descriptions. In relation to space use, only broad features are available for the entire distribution range of Eurasian Bullfnches, including Iberia. Methods: In this study, seasonal preferences regarding habitat and space in a population of Eurasian Bullfnches are examined for the frst time in the Iberian Peninsula, through direct observation during a six-year period. The essential habitat components, substrate selection and perch height were assessed. Results: Hedgerows were the key essential habitat component for bullfnches during all seasons. Nevertheless, small poplar plantations became increasingly important from winter to summer-autumn. Bullfnches perched mostly in shrubs/trees throughout the year, but there were signifcant seasonal changes in substrate use, ground and herbs being of considerable importance during spring-summer. Throughout the year, over half of the records corresponded to feeding, reaching almost 90% in winter. Generally, bullfnches perched noticeably lower while feeding. Male bullfnches perched markedly higher than females, notably singing males in spring-summer. Juveniles perched at a height not much lower than that of males. -

English Ivy (Hedera Helix)

W231 English Ivy (Hedera helix) Becky Koepke-Hill, Extension Assistant, Plant Sciences Greg Armel, Assistant Professor, Extension Weed Specialist for Invasive Weeds, Plant Sciences Origin: English ivy is native to Europe, from northeastern Ireland to southern Scandinavia, and south to Spain. It is also native in western Asia and northern Africa. English ivy arrived in North America as a landscape plant and escaped from those landscape settings into natural areas. Description: This evergreen perennial vine can grow up to 90 feet with proper support. English ivy has two forms: juvenile and mature. Juvenile plants have leaves with three to five lobes and herbaceous stems or very thin woody stems. Mature plants have leaves with no lobes and thick woody stems, with a primary support- ing stem containing hairs similar to poison ivy. The supporting stem grows up trees or walls. Most English ivy plants in landscapes are juvenile plants. Both mature and juvenile plants have leaves with smooth edges, which are dark green with white or pale green veins. Small, inconspicuous flowers appear in the fall on mature stems and produce dark blue to black fruits. Habitat: English ivy grows in fields, hedgerows, woodlands, forest edges and upland areas. It does not thrive in wet or extremely moist areas, but will grow in a wide range of soil pH. New populations generally occur on land that has been disturbed by humans or natural occurrences. Environmental Impact: English ivy grows into thick carpets on forest floors, crowding out native vegetation, and it is one of few exotic plants that can thrive in full, deep shade. -

Intriguing World of Weeds Iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii

Intriguing World of Weeds iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii Poison-Ivy/Poison-Oak/Poison-Sumac-The Virulent Weeds 1 LARRY W. MITICH2 I I; INTRODUCTION I, ii The word poison entered the English language in 1387 as 'poysoun" (18), and in Memoirs ofAmerican Academy of Arts and Sciences, v. 1, 1785, the word poison-ivy was used for the first time: "Poison ivy ... produces the same kind of inflammation and eruptions . as poison wood tree" (18). · The first known reference to poison-ivy, Toxicodendron radicans (L.) Ktze., dates from the 7th century in China and the 10th century in Japan. Since Toxicodendron species do not grow in Europe, the plants re mained unknown to Western civiliza tion until explorers visited the New World seven centuries later (7). Capt. John Smith (1579-1631) wrote the first description of poison-ivy and origi nated its common name; he noted a similarity in the climbing habit of They used that name for a shrub of the Southern States, North American poison-ivy to English with crenately-lobed, very pubescent leaflets (1). ivy (Hedera helix L.) (7). Toxicodendron, a pre-Linnaean name, was not accepted Joseph Pitton de Tournefort (1656-1708) established at the generic level by Linnaeus. Tournefort limited the the genus for poison-ivy in lnstitutiones rei herbariae, v. genus to ternate-leaved plants, thus omitting such close 1, p. 610, 1700 (7). The name is from the Latin for poison relatives of poison-ivy as poison-sumac and the oriental ous tree (9). lacquer tree (7). The lacquer tree has been known for In 1635 Jacques Philippe Cornut ( 1601-1651) wrote the first book on Canadian botany (Canadensium Plantarum thousands of years, and descriptions of the inflammations aliarumque nondum editarum historia, Parisiis [Paris]). -

English Ivy (Hedera Helix)

KING COUNTY NOXIOUS WEED ALERT Non-Regulated Class C English Ivy* Noxious Weed: Control Hedera helix Ginseng Family Recommended Identification Tips • Woody, evergreen, perennial vine, trailing or climbing • Leaves on non-flowering stems (juvenile stage):dull green, lobed, with distinct light veins; stems produce roots at nodes; most common leaf type on plant • Leaves on flowering stems (mature stage):glossy green, unlobed; stems produce umbrella-like clusters of greenish flowers, followed by dark berry-like fruits • Ivy plants can have both juvenile and mature stems • Vines typically grow 90 feet long with stems up to one foot in diameter; can grow up 300-foot trees. Juvenile ivy leaves are dull green and deeply lobed, with distinct light veins. Biology Climbing vines form small rootlets that have a glue-like substance to attach to any surface. Spreads vegetatively via creeping stems and roots. Once mature, also spreads by bird-dispersed seeds found in berry-like fruits. Flowers in the fall; fruits mature in early spring. Roots are long and mostly creeping (usually 1-4 inches deep). Plants are long-lived, 50 to 100 years or more. Impacts Provides hiding places for rats and other vermin. In natural areas, crowds out native plants and takes over the forest floor. Adds substantial weight to trees, which can contribute to blowdowns. Forms thick mats that Mature ivy stems have fuller, glossy, can accelerate rot and deteriorate structures. Shallow-rooted ivy mats unlobed leaves and produce clusters of black fruit. on hillsides can increase risk of slope slippage. Entire plant contains somewhat toxic compounds; sap can cause rashes in some people.