Che in Bolivia: 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Delegation of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ireland (Marxist-Leninist) Returns from Visit to Albania

Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line Anti-revisionism in Ireland Delegation of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ireland (Marxist-Leninist) Returns from Visit to Albania Published: Red Patriot, newspaper of the Communist Party of Ireland (Marxist-Leninist), May 21, 1978.) Transcription, Editing and Markup: Paul Saba and Sam Richards Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti- Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above. Recently a Central Committee delegation of the Communist Party of Ireland (Marxist-Leninist) returned from a visit to the People's Socialist Republic of Albania, where it was hosted by the Central Committee of the Party of Labor of Albania. The delegation saw at first hand the great achievements of the Albanian people under the leadership of the great Party of Labor of Albania led by Comrade Enver Hoxha. The Party of Labor of Albania has distinguished itself by its persistent adherence to principle and its refusal to capitulate to any form of revisionism. It opposed the revisionism of Tito right from the outset. It opposed the revisionism of the Khrushchev clique and the Soviet revisionists as soon as it appeared. Today, the Party of Labor of Albania has taken a resolute stand against the new revisionists pushing the reactionary theory of three worlds. The Party of Labor of Albania has played an outstanding role in the struggle against revisionism of all kinds and has won the deepest respect of all genuine Marxist-Leninists and progressive people throughout the world. -

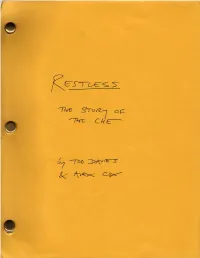

Restless.Pdf

RESTLESS THE STORY OF EL ‘CHE’ GUEVARA by ALEX COX & TOD DAVIES first draft 19 jan 1993 © Davies & Cox 1993 2 VALLEGRANDE PROVINCE, BOLIVIA EXT EARLY MORNING 30 JULY 1967 In a deep canyon beside a fast-flowing river, about TWENTY MEN are camped. Bearded, skinny, strained. Most are asleep in attitudes of exhaustion. One, awake, stares in despair at the state of his boots. Pack animals are tethered nearby. MORO, Cuban, thickly bearded, clad in the ubiquitous fatigues, prepares coffee over a smoking fire. "CHE" GUEVARA, Revolutionary Commandant and leader of this expedition, hunches wheezing over his journal - a cherry- coloured, plastic-covered agenda. Unable to sleep, CHE waits for the coffee to relieve his ASTHMA. CHE is bearded, 39 years old. A LIGHT flickers on the far side of the ravine. MORO Shit. A light -- ANGLE ON RAUL A Bolivian, picking up his M-1 rifle. RAUL Who goes there? VOICE Trinidad Detachment -- GUNFIRE BREAKS OUT. RAUL is firing across the river at the light. Incoming bullets whine through the camp. EVERYONE is awake and in a panic. ANGLE ON POMBO CHE's deputy, a tall Black Cuban, helping the weakened CHE aboard a horse. CHE's asthma worsens as the bullets fly. CHE Chino! The supplies! 3 ANGLE ON CHINO Chinese-Peruvian, round-faced and bespectacled, rounding up the frightened mounts. OTHER MEN load the horses with supplies - lashing them insecurely in their haste. It's getting light. SOLDIERS of the Bolivian Army can be seen across the ravine, firing through the trees. POMBO leads CHE's horse away from the gunfire. -

1992 a Glorious Model of Proletarian Internationalism: Mao Zedong and Helping Vietnam Resist France

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified 1992 A Glorious Model of Proletarian Internationalism: Mao Zedong and Helping Vietnam Resist France Citation: “A Glorious Model of Proletarian Internationalism: Mao Zedong and Helping Vietnam Resist France,” 1992, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Luo Guibo, "Wuchanjieji guojizhuyide guanghui dianfan: yi Mao Zedong he Yuan-Yue Kang-Fa" ("A Glorious Model of Proletarian Internationalism: Mao Zedong and Helping Vietnam Resist France"), in Mianhuai Mao Zedong (Remembering Mao Zedong), ed. Mianhuai Mao Zedong bianxiezhu (Beijing: Zhongyang Wenxian chubanshe, 1992) 286-299. Translated by Emily M. Hill http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/120359 Summary: Luo Guibo recounts China's involvement in the First Indochina War and its assistance to the Viet Minh. Credits: This document was made possible with support from the MacArthur Foundation and the Leon Levy Foundation. Original Language: Chinese Contents: English Translation One Late in 1949, soon after the establishment of New China, Chairman Ho Chi Minh and the Central Committee of the Indochinese Communist Party (ICP) wrote to Chairman Mao and the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), asking for Chinese assistance. In January 1950, Ho made a secret visit to Beijing to request Chinaʼs assistance in Vietnamʼs struggle against France. Following Hoʼs visit, the CCP Central Committee made the decision, authorized by Chairman Mao, to send me on a secret mission to Vietnam. I was formally appointed as the Liaison Representative of the CCP Central Committee to the ICP Central Committee. Comrade [Liu] Shaoqi personally composed a letter of introduction, which stated: ʻI hereby recommend to your office Comrade Luo Guibo, who has been a provincial Party secretary and commissar, as the Liaison Representative of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party. -

Moscow Takes Command: 1929–1937

Section 3 Moscow takes command: 1929–1937 The documents in this section cover the period from February 1929 until early 1937, with most of them being concentrated in the earlier years of this period in line with the general distribution of documents in the CAAL. This period marks an important shift in the history of relations between the CPA and the Comintern for two main reasons. First, because the Comintern became a direct player in the leadership struggles within the Party in 1929 (the main catalyst for which, not surprisingly, was the CPA's long-troubled approach to the issue of the ALP). And second, because it sent an organizer to Australia to `Bolshevize' the Party in 1930±31. A new generation of leaders took over from the old, owing their positions to Moscow's patronage, and thusÐuntil the Party was declared an illegal organization in 1940Ðfully compliant with the policies and wishes of Moscow. The shift in relations just outlined was part of a broader pattern in the Comintern's dealings with its sections that began after the Sixth Congress in 1928. If the `Third Period' thesis was correct, and the world class struggle was about to intensify, and the Soviet Union to come under military attack (and, indeed, the thesis was partly correct, but partly self-fulfilling), then the Comintern needed sections that could reliably implement its policies. The Sixth Congress had been quite open about it: it now required from its national sections a `strict party discipline and prompt and precise execution of the decisions of the Communist International, of its agencies and of the leading Party committees' (Degras 1960, 466). -

Open Letter to the Communist Party of the Philippines

32 1*3 •if From the Committee of the The following Open Letter and women under arms and which seriously with the problems of line was forwarded to A World to Win has set ablaze a people's war which threaten the revolutionary by the Information Bureau of the throughout the Philippines, was left character of your party and the peo• RIM. It is published in full; the paralyzed by the march of events, ple's war it is leading. subheads have been added by or worse, trailing in their wake. In• This is a matter of serious impor• AWTW. deed, the inability of the CPP to tance not only for the destiny of the oo To the Central Committee find its bearings amidst the political Philippine revolution, but for the Communist Party of the Philippines crisis and ultimate fall of the Mar• proletarian revolutionary move• co cos regime in order to carry forward ment around the world. At its foun• ». Comrades, the revolutionary war has now given ding the CPP declared that the > It is with the most dramatically rise to political crisis in the CPP Philippine revolution was a compo• ^ conflicting emotions that the Com- itself, and even to mounting tenden• nent part of the world proletarian S mittee of the Revolutionary Inter- cies towards outright capitulation. revolution. And indeed it is. The Q nationalist Movement has viewed This situation has arisen after CPP itself was born in the flames *"* the unfolding of events over the past several years in which Marxist- of the international battle against Q year in the Philippines. -

De Ernesto, El “Che” Guevara: Cuatro Miradas Biográficas Y Una Novela*

Literatura y Lingüística N° 36 ISSN 0716 - 5811 / pp. 121 - 137 La(s) vida(s) de Ernesto, el “Che” Guevara: cuatro miradas biográficas y una novela* Gilda Waldman M.** Resumen La escritura biográfica, como género, alberga en su interior una gran diversidad de métodos, enfoques, miradas y modelos que comparten un rasgo central: se trata de textos interpre- tativos, pues ningún pasado individual se puede reconstruir fielmente. En este sentido, cabe referirse a algunas de las más importantes biografías existentes sobre el Che Guevara, como La vida en rojo, de Jorge G. Castañeda, (Alfaguara 1997); Che Ernesto Guevara. Una leyenda de nuestro siglo, de Pierre Kalfon (Plaza y Janés, 1997); Che Guevara. Una vida revo- lucionaria, de John Lee Anderson (Anagrama, 2006) y Ernesto Guevara, también conocido como el Che, de Paco Ignacio Taibo II (Planeta, 1996). Por otro lado, en la vida del Che, hay silencios oscuros que las biografías no cubren, salvo de manera muy superficial. Algunos de estos vacíos son retomados por la literatura, por ejemplo, a través de la novela de Abel Posse, Los Cuadernos de Praga. Palabras clave: Che Guevara, biografías, interpretación, literatura. Ernesto “Che” Guevara’s Lives. Four Biographies and one Novel Abstract The biographical writing, as a genre, shelters inside a wide diversity of methods, approaches, points of view and models that share a central trait: it is an interpretative text, since no individual past can be faithfully reconstructed. In this sense, it is worth referring to some of the most diverse and important biographies written about Che Guervara, (Jorge G. Castañeda: La vida en rojo, Alfaguara 1997; Pierre Kalfon: Che Ernesto Guevara. -

Press Release Author A.C. Frieden Follows Che Guevara's Trail in Bolivia

Press Release Author A.C. Frieden Follows Che Guevara’s Trail in Bolivia VALLEGRANDE, Bolivia (Nov. 22, 2007) -- Author A.C. Frieden traveled to Bolivia to research Che Guevara’s 1960s revolutionary movement in order to complete his upcoming novel Where Spies Go To Die. Arriving in Santa Cruz, Bolivia’s largest city and one of the transit points for Che Guevara and his rebels in 1966, Frieden visited many of the city’s key sites and interviewed a number of locals in preparation for his journey south. Above: Monument dedicated to Che Guevara located in the center of the tiny village of La Higuera, in south-central Bolivia, where the guerrilla leader was executed in 1967. After visiting Samaipata, he went on to Vallegrande to see various sites related to Che Guevara. In particular, Frieden visited the Señor de Malta hospital, where Che’s body was flown to after his execution in La Higuera. Frieden toured the airfield and nearby grounds where Che’s remains and those of his most loyal comrades were secretly buried in 1967. For several days Frieden ventured south from Vallegrande across rugged mountain roads to visit remote villages and trails connected to Che Guevara’s doomed rebellion. After visiting the town of Pucara, Frieden arrived in La Higuera and toured the schoolhouse where Che was executed by CIA-backed Bolivian troops shortly after his capture in the nearby canyon called Quebrada de Yuro. In La Higuera, Frieden interviewed a village elder who had witnessed Che’s arrival into the village 40 years earlier. Frieden returned to Samaipata, where he toured El Fuerte, an archeological site (designated a world heritage site by UNESCO) that was inhabited by three populations over several centuries: the Amazonian, Inca and Colonial civilizations. -

Huellas De Tania

Cuidado de la edición: Tte Cor. Ana Dayamín Montero Díaz Edición: Olivia Diago Izquierdo Diseño de cubierta e interior: Liatmara Santiesteban García Realización: Yudelmis Doce Rodríguez Corrección: Catalina Díaz Martínez Fotos: Cortesía de los autores © Adys Cupull Reyes, 2019 Froilán González García, 2019 © Sobre la presente edición: Casa Editorial Verde Olivo, 2020 ISBN: 978-959-224-478-8 Todos los derechos reservados. Esta publicación no puede ser reproducida, ni en todo ni en parte, en ningún soporte sin la autorización por escrito de la editorial. Casa Editorial Verde Olivo Avenida de Independencia y San Pedro Apartado 6916. CP 10600 Plaza de la Revolución, La Habana [email protected] www.verdeolivo.cu «Lo más valioso que un hombre posee es la vida, se le da a él solo una vez y por ello debe aprovecharla de manera que los años vividos no le pesen, que la vergüenza de un pasado mezquino no le queme y que muriendo pueda decir, he consagrado toda mi vida y mi gran fuerza a lo más hermoso del mundo, a la lucha por la liberación de la humanidad». NICOLÁS OSTROVKI «...es tarea nuestra mantenerla viva en todas las formas». VILMA ESPÍN GUILLOIS Índice NOTA AL LECTOR / 5 UNA MUCHACHA ARGENTINA EN ALEMANIA / 14 UNA ARGENTINA EN CUBA / 27 MISIÓN ESPECIAL / 48 NACE EN PRAGA LAURA GUTIÉRREZ BAUER / 59 VIAJE A MÉXICO Y REGRESO A BOLIVIA / 87 EN LAS SELVAS DE ÑACAHUASÚ / 106 TANIA EN LA RETAGUARDIA GUERRILLERA / 111 UN SOBREVIVIENTE DE LA RETAGUARDIA / 120 POMBO HABLA DE LA RETAGUARDIA / 131 ASESINATOS EN BOLIVIA / 140 TANIA EN VALLEGRANDE / 145 EL POEMA A ITA / 154 PRESENCIA DE TANIA / 161 HOMENAJES DESDE ÑACAHUASÚ / 168 SOLIDARIDAD DE LOS VALLEGRANDINOS / 175 HUELLAS INDELEBLES / 180 ANEXOS / 190 TESTIMONIO GRÁFICO / 198 AGRADECIMIENTOS / 224 BIBLIOGRAFÍA / 227 Nota al lector Huellas de Tania es el título de esta obra para la cual hemos indaga- do y compilado informaciones basadas en la vida de Haydée Tamara Bunke Bíder, Tania la Guerrillera. -

The Beginning of the End: the Political Theory of the Gernian Conmunist Party to the Third Period

THE BEGINNING OF THE END: THE POLITICAL THEORY OF THE GERNIAN CONMUNIST PARTY TO THE THIRD PERIOD By Lea Haro Thesis submitted for degree of PhD Centre for Socialist Theory and Movements Faculty of Law, Business, and Social Science January 2007 Table of Contents Abstract I Acknowledgments iv Methodology i. Why Bother with Marxist Theory? I ii. Outline 5 iii. Sources 9 1. Introduction - The Origins of German Communism: A 14 Historical Narrative of the German Social Democratic Party a. The Gotha Unity 15 b. From the Erjlurt Programme to Bureaucracy 23 c. From War Credits to Republic 30 II. The Theoretical Foundations of German Communism - The 39 Theories of Rosa Luxemburg a. Luxemburg as a Theorist 41 b. Rosa Luxemburg's Contribution to the Debates within the 47 SPD i. Revisionism 48 ii. Mass Strike and the Russian Revolution of 1905 58 c. Polemics with Lenin 66 i. National Question 69 ii. Imperialism 75 iii. Political Organisation 80 Summary 84 Ill. Crisis of Theory in the Comintern 87 a. Creating Uniformity in the Comintern 91 i. Role of Correct Theory 93 ii. Centralism and Strict Discipline 99 iii. Consequencesof the Policy of Uniformity for the 108 KPD b. Comintern's Policy of "Bolshevisation" 116 i. Power Struggle in the CPSU 120 ii. Comintern After Lenin 123 iii. Consequencesof Bolshevisation for KPD 130 iv. Legacy of Luxemburgism 140 c. Consequencesof a New Doctrine 143 i. Socialism in One Country 145 ii. Sixth Congress of the Comintern and the 150 Emergence of the Third Period Summary 159 IV. The Third Period and the Development of the Theory of Social 162 Fascism in Germany a. -

Download The

Las formas del duelo: memoria, utopía y visiones apocalípticas en las narrativas de la guerrilla mexicana (1979-2008) by José Feliciano Lara Aguilar B.J., Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 2001 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Hispanic Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) October 2016 © José Feliciano Lara Aguilar, 2016 Abstract This study analyzes six literary works of the Mexican contemporary guerrilla that covers the years 1979 to 2008: Al cielo por asalto (1979) by Agustín Ramos, ¿Por qué no dijiste todo? (1980) and La patria celestial (1992) by Salvador Castañeda, Morir de sed junto a la fuente. Sierra de Chihuahua 1968 (2001) by Minerva Armendáriz Ponce, Veinte de cobre (2004) by Fritz Glockner, and Vencer o morir (2008) by Leopoldo Ayala. In both their form and structure, these narratives address the notion of mourning, as well as its inherent categories, such as: work of mourning or grief work, melancholy, loss, grief, remnants, and specters, among others, which call into question and destabilize the generalized social discourse. In this tension, I observe the emergence of aesthetic languages that take place within the post-revolutionary imaginary of the 1960’s, and 1970’s with the exhaustion of revolutionary imaginary that was predominant in the preceding decades. These aesthetic languages provide mourning with new contents, organized in three fields: memory, utopia, and apocalyptic visions, which recreate mourning as a symbolic space where an important social struggle for the reconstruction of the past is still ongoing. -

On Democratic Centralism

The Marxist, XXVI 1, January–March 2010 PRAKASH KARAT On Democratic Centralism In the recent period, alongwith a number of critical discussions on the electoral set-back suffered by the CPI (M) and the Left in last Lok Sabha elections, there have been some questions raised about the practice of democratic centralism as the organizational principle of the Communist Party. Such critiques have come from persons who are intellectuals associated with the Left or the CPI (M). Since such views are being voiced by comrades and persons who are not hostile to the Party, or, consider themselves as belonging to the Left, we should address the issues raised by them and respond. This is all the more necessary since the CPI (M) considers the issue of democratic centralism to be a basic and vital one for a party of the working class. Instead of dealing with each of the critiques separately, we are categorising below the various objections and criticisms made. Though, it must be stated that it is not necessary that each of them hold all the views expressed by the others. But the common refrain is that democratic centralism should not serve as the organizational principle of the Communist Party or that it should be modified. What are the points made in these critiques? They can be summed up as follows: THE MARXIST 1. Democratic centralism is characterized as a Party organizational structure fashioned by Lenin to meet the specific conditions of Tsarist autocracy which was an authoritarian and repressive regime. Hence, its emphasis on centralization, creating a core of professional revolutionaries and secrecy. -

El Che Entre El Ideal Y La Reproducción, (Trayectoria De Una Imagen)..Pdf

UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DEL ESTADO DE MÉXICO FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS POLÍTICAS Y SOCIALES “EL CHE, ENTREL EL IDEAL Y LA REPRODUCCIÓN” (TRAYECTORIA DE UNA IMAGEN) ENSAYO PARA OBTENER EL TÍTULO DE: LICENCIADA EN COMUNICACIÓN PRESENTA YESABELL RODRÍGUEZ CHIMAL DIRECTOR DE ENSAYO DR. GUSTAVO GARDUÑO OROPEZA TOLUCA, ESTADO DE MÉXICO NOVIEMBRE 2018 1 Agradecimientos Ver un trabajo concluido es más de lo que puede aparentar, tenerlo entre las manos remite el esfuerzo que implicó cada letra y tilde, a su vez remonta a los que hicieron posible esto, gracias a todos los que dieron algo de su luz para vislumbrar este trabajo; a María de Jesús. En memoria de la estrella de la boina del Che… A Xitlali Rodríguez. Índice Presentación..…………………………………………………………………………………………………........3 Capitulo 1. “El Che de la Foto” 1.1 El Che ………....……………………………………………..…………………………................................7 1.2 Chesus………....……………………………………………..…………………………...............................9 1.3 ¿Quién es el Che?………....……………………………………………..………………………………….13 1.3.1 Guevara Ciudadano de América Latina ………………………………………………………………...15 1.4 La revolución y la guerrilla…………………………………………………………………………………..20 1.4.1 La ideología como parte de la guerrilla. …………………………………......................................…21 1.4.2 La comunicación como papel fundamental en la guerrilla…………………………….………………30 1.4.3 Che en Bolivia la última guerrilla……………………………………………………………………..…..33 Capitulo 2. La historia de una fotografía de la revolución y su masificación. 2.1 Historia de un instante…………………………………..…………………………...................................37 2.2 Una retrospectiva a las fotos de Ernesto Guevara de la Serna……..…………………………............40 2.3 La apropiación de la propiedad intelectual y su reproducción masiva………………………..……..... 45 Capitulo 3. El Guerrillero Heroico y la composición fotográfica. 3.1. La importancia de una imagen fotográfica. ………..........……………………………………...............53 3.2 El Guerrillero Heroico y la composición fotográfica……………………………………………………....61 3.2.1 Regla de los tercios……………………………………………………………………………………….