Lyndon B. Johnson Power

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chicken Wire and Telephone Calls: on Robert Caro

30 The Nation. December 10, 2012 LBJ PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY/YOICHI OKAMOTO LBJ PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY/YOICHI President Lyndon B. Johnson, October 22, 1968 Chicken Wire and Telephone Calls by THOMAS MEANEY obert Caro has been tracking his great The Years of Lyndon Johnson simply to be always the greediest, most ambi- white whale for thirty years now. As The Passage of Power. tious and ruthless man in the room. with any undertaking of this scale, an By Robert A. Caro. This is a serious criticism, but like the Knopf. 712 pp. $35. aura of legend attaches to the labor. journalistic halo over Caro, it confuses First there is the Ahab-like devotion to post-1960 scholarship. All of this fact- the trappings of his achievement for its Rwith which he has pursued the life of Lyndon hunting and what you might call Method core. Caro has always been more valuable Baines Johnson. In 1977, not long after pub- research has made Caro—who started his as a guide to how power works in postwar lishing his epic biography of Robert Moses, career as a reporter for Newsday—something America in particular than how it works New York City’s master builder, Caro de- of a hero for American journalists: he is the in some general abstract sense. Biography camped to Texas Hill Country for three years guildsman who made good and raised their would not initially seem to be the form best to take in the air of LBJ’s childhood. He spent craft to a level that academics can only envy. -

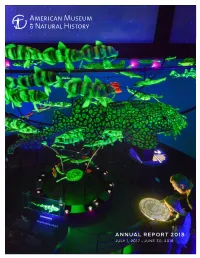

Annual Report 2018

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 JULY 1, 2017 – JUNE 30, 2018 be out-of-date or reflect the bias and expeditionary initiative, which traveled to SCIENCE stereotypes of past eras, the Museum is Transylvania under Macaulay Curator in endeavoring to address these. Thus, new the Division of Paleontology Mark Norell to 4 interpretation was developed for the “Old study dinosaurs and pterosaurs. The Richard New York” diorama. Similarly, at the request Gilder Graduate School conferred Ph.D. and EDUCATION of Mayor de Blasio’s Commission on Statues Masters of Arts in Teaching degrees, as well 10 and Monuments, the Museum is currently as honorary doctorates on exobiologist developing new interpretive content for the Andrew Knoll and philanthropists David S. EXHIBITION City-owned Theodore Roosevelt statue on and Ruth L. Gottesman. Visitors continued to 12 the Central Park West plaza. flock to the Museum to enjoy the Mummies, Our Senses, and Unseen Oceans exhibitions. Our second big event in fall 2017 was the REPORT OF THE The Gottesman Hall of Planet Earth received CHIEF FINANCIAL announcement of the complete renovation important updates, including a magnificent OFFICER of the long-beloved Gems and Minerals new Climate Change interactive wall. And 14 Halls. The newly named Allison and Roberto farther afield, in Columbus, Ohio, COSI Mignone Halls of Gems and Minerals will opened the new AMNH Dinosaur Gallery, the FINANCIAL showcase the Museum’s dazzling collections first Museum gallery outside of New York STATEMENTS and present the science of our Earth in new City, in an important new partnership. 16 and exciting ways. The Halls will also provide an important physical link to the Gilder All of this is testament to the public’s hunger BOARD OF Center for Science, Education, and Innovation for the kind of science and education the TRUSTEES when that new facility is completed, vastly Museum does, and the critical importance of 18 improving circulation and creating a more the Museum’s role as a trusted guide to the coherent and enjoyable experience, both science-based issues of our time. -

Overcoming Financial and Institutional Barriers to TOD: Lindbergh Station Case Study

Overcoming Financial and Insitutional Barriers to TOD Overcoming Financial and Institutional Barriers to TOD: Lindbergh Station Case Study Eric Dumbaugh Abstract While transit-oriented development has been embraced as a strategy to address a wide range of planning objectives, from minimizing automobile dependence to im- proving quality of life, there has been almost no examination into the practices that have resulted in the actual development of one. This study examines Atlanta’s Lindbergh Station TOD to understand how a real-world development was able to overcome the substantial development barriers that face these developments. It finds that transit agencies have a largely underappreciated ability to overcome the land assembly and project financing barriers that have heretofore prevented the develop- ment of these projects. Further, because they provide a means from converting capi- tal investment into positive operating returns, this study finds that development projects provide transit agencies with a unique means of overcoming the capital bias in funding apportionment mechanisms. This latter factor will undoubtedly play a key role in increasing the popularity of transit-agency sponsored TOD projects in the future. 43 Journal of Public Transportation, Vol. 7, No. 3, 2004 Introduction Transit-oriented development (TOD), which seeks to encourage transit and walk- ing as a travel mode by clustering mixed-use, higher density development around transit stations (Calthorpe 1993), has become popularly embraced as a strategy for mitigating a host of social ills, such as sprawl, automobile dependence, travel congestion, air pollution, and physical health, among others (Belzer and Autler 2002; Cervero et al. 2002; Frank et al. -

2019 BIO Program Rev3.Indd

MAY 17–1 9, 2019 BIOGRAPHERS INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE NEW YORK CITY LEON LEVY CENTER FOR BIOGRAPHY THE GRADUATE CENTER CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK The 2019 Plutarch Award Biographers International Organization is proud to present the Plutarch Award for the best biography of 2018, as chosen by our members. Congratulations to the ten nominees: The 2019 BIO Award Recipient: James McGrath Morris James McGrath Morris first fell in love with biography as a child reading newspaper obituaries. In fact, his steady diet of them be- came an important part of his education in history. In 2005, after a career as a journalist, an editor, a book publisher, and a school- teacher, Morris began writing books full-time. Among his works are Jailhouse Journalism: The Fourth Estate Behind Bars; The Rose Man of Sing Sing: A True Tale of Life, Murder, and Redemption in the Age of Yellow Journalism; Pulitzer: A Life in Politics, Print, and Power; Eye on the Struggle: Ethel Payne, The First Lady of the Black Press, which was awarded the Benjamin Hooks National Book Prize for the best work in civil rights history in 2015; and The Ambulance Drivers: Hemingway, Dos Passos, and a Friendship Made and Lost in War. He is also the author of two Kindle Singles, The Radio Operator and Murder by Revolution. In 2016, he taught literary journalism at Texas A&M, and he has conducted writing workshops at various colleges, universities, and conferences. He is the progenitor of the idea for BIO and was among the found- ers as well as a past president. -

Value Added: Jews in Postwar American Culture 69

Value Added: Jews in Postwar American completely secularized, even surpas. skepticism. So complete ~ triur Bless America" (1918, rev. 1938rcOl: Value Added: Jews in Postwar gled Banner" as the national antherr remember. The principle of separatiOi American Culture obstacle. 2 Until the early 1960s, however, th. pluralism were unrealized. Although Stephen J. Whitfield dency has not recurred, John F. Ker (BRANDEIS UNIVERSITY) longer necessary for the holder of the years later, another symbolic defeal conformity with the landmark U.S. Though Protestantism had long unoft the country, the Supreme Court bann five New York children challenged Americans are "descended from the same ancestors, speaking the same language, graders was eleven-year-old Joe Rotn professing the same religion, attached to the same principles of government, very graduation, he later recalled, some of similar in their manners and customs," John Jay wrote in The Federalist No.2, in before talking to him.) The shock Wi defense of the new Constitution. 1 At least he got the politics right: All the basic Long Island and across the country. A political institutions of the United States had been created by the end of the eigh the Supreme Court's ruling, and lib· teenth century, and none since then. But the Framers could scarcely have imagined their outrage. Two years later, the Re how the culture would keep shifting into new configurations. Regional and ethnic whether 1964 was "the time for our I customs would vary widely, new languages would get injected (at least for one or our school rooms"; and a conservativ two generations) and religious pluralism would become legitimated, largely because increasing antisemitism if the Jews ~ Americans increasingly did not have the same ancestors. -

A Republic...If You Can Keep It Essays and Reviews by Michael Burlingame, Charles C

VOLUME XIII, NUM BER 1, WINTER 2012/13 A Journal of Political Thought and Statesmanship A Republic...If You Can Keep It Essays and Reviews by Michael Burlingame, Charles C. Johnson, Michael Nelson, Ronald J. Pestritto, Richard Vedder, William Voegeli, and Ryan P. Williams Plus Victor Davis James Hankins: Hanson: Christopher Caldwell: Protestants Algis Valiunas: Imperial Burdens Gay Rites Gone Wild Leo Tolstoy Martha Bayles: Cheryl Miller: Benjamin Balint: Lincoln & Downton Abbey Salman Rushdie Django Unchained PRICE: $6.95 IN CANADA: $6.95 mmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmm Book Review by Michael Nelson Too Much Information The Passage of Power: The Years of Lyndon Johnson, by Robert A. Caro. Alfred A. Knopf, 736 pages, $35 obert a. caro began working on Caro turned 77 in October, however, and has Caro’s interpretation. Although the Johnson a biography of Lyndon Johnson in been requiring more time to account for his of Lone Star Rising and Flawed Giant is almost R1974, the year he published his award- subject’s life, which is understandable since it as unattractive as the man Caro describes, winning The Power Broker: Robert Moses and grew increasingly complex and consequential. Dallek argued that Johnson’s personal ambi- the Fall of New York. He meant The Years of At every stage of The Years of Lyndon Johnson, tion served a larger lifelong cause: to integrate Lyndon Johnson to be a six-year, three-volume Caro has underestimated the number of in- the South into the nation by developing its project. Instead, Caro’s first volume,The Path stallments to come and the number of years economy and ending racial segregation. -

David Greenberg

DAVID GREENBERG Professor of History Professor of Journalism & Media Studies Rutgers University, The State University of New Jersey 4 Huntington Street, New Brunswick, NJ 08901 646.504.5071 • [email protected] Education. Columbia University, New York, NY. PhD, History. 2001. MPhil, History. 1998. MA, History. 1996. Yale University, New Haven, CT. BA, History. 1990. Summa cum laude. Phi Beta Kappa. Distinction in the major. Academic Positions. Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ. Professor, Departments of History and Journalism & Media Studies. 2016- . Associate Professor, Departments of History and Journalism & Media Studies. 2008-2016. Assistant Professor, Department of Journalism & Media Studies. 2004-2008. Appointment to the Graduate Faculty, Department of History. 2004-2008. Affiliation with Department of Political Science. Affiliation with Department of Jewish Studies. Affiliation with Eagleton Institute of Politics. Columbia University, New York, NY. Visiting Associate Professor, Department of History, Spring 2014. Yale University, New Haven, CT. Lecturer, Department of History and Political Science. 2003-04. American Academy of Arts & Sciences, Cambridge MA. Visiting Scholar. 2002-03. Columbia University, New York, NY. Lecturer, Department of History. 2001-02. Teaching Assistant, Department of History. 1996-99. Greenberg, CV, p. 2. Other Journalism and Professional Experience. Politico Magazine. Columnist and Contributing Editor, 2015- The New Republic. Contributing Editor, 2006-2014. Moderator, “The Open University” blog, 2006-07. Acting Editor (with Peter Beinart), 1996. Managing Editor, 1994-95. Reporter-researcher, 1990-91. Slate Magazine. Contributing editor and founder of “History Lesson” column, the first regular history column by a professional historian in the mainstream media. 1998-2015. Staff editor, culture section, 1996-98. The New York Times. -

HERITAGE NEWSLETTER of the AMERICAN JEWISH HISTORICAL SOCIETY VOLUME 1, NUMBER 1 • SPRING 2003 CONTENTS a Letter From

H E R I T A G E VOL.1 NO.1 NEWSLETTER OF THE AMERICAN JEWISH HISTORICAL SOCIETY SPRING 2003 Posters from the past. A sampling of posters from the golden age of Yiddish theatre. Pages 14 -15. 350th Anniversary Emma Lazarus Awardee Baseball Card Collectors Edition American Jewish Historical Society 2002 -2003 Gift Roster Over $200,000 Genevieve & Justin L. Wyner $100,000 + Ann E. & Kenneth J. Bialkin Marion & George Blumenthal Ruth & Sidney Lapidus Barbara & Ira A. Lipman $25,000 + Citigroup Foundation Mr. David S. Gottesman Yvonne S. & Leslie M. Pollack Dianne B. and David J. Stern The Horace W. Goldsmith Linda & Michael Jesselson Nancy F. & David P. Solomon Mr. and Mrs. Sanford I. Weill Foundation Sandra C. & Kenneth D. Malamed Diane & Joseph S. Steinberg $10,000 + Mr. S. Daniel Abraham Edith & Henry J. Everett Mr. Jean-Marie Messier Muriel K. and David R Pokross Mr. Donald L. SaundersDr. and Elsie & M. Bernard Aidinoff Stephen and Myrna Greenberg Mr. Thomas Moran Mrs. Nancy T. Polevoy Mrs. Herbert Schilder Mr. Ted Benard-Cutler Mrs. Erica Jesselson Ruth G. & Edgar J. Nathan, III Mr. Joel Press Francesca & Bruce Slovin Mr. Len Blavatnik Renee & Daniel R. Kaplan National Basketball Association Mr. and Mrs. James Ratner Mr. Stanley Snider Mr. Edgar Bronfman Mr. and Mrs. Norman B. Leventhal National Hockey League Foundation Patrick and Chris Riley aMrs. Louise B. Stern Mr. Stanley Cohen Mr. Leonard Litwin Mr. George Noble Ambassador and Mrs. Felix Rohatyn Mr. Steve Stowe Combined Jewish Philanthropies Ms. Deborah B. Marin Ann & Jeffrey S. Oppenheim Louise P. & Gabriel Rosenfeld Adele & Ronald S. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Benjamin Henry Latrobe by Talbot Faulkner Hamlin Benjamin Henry Latrobe by Talbot Faulkner Hamlin

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Benjamin Henry Latrobe by Talbot Faulkner Hamlin Benjamin Henry Latrobe by Talbot Faulkner Hamlin. Our systems have detected unusual traffic activity from your network. Please complete this reCAPTCHA to demonstrate that it's you making the requests and not a robot. If you are having trouble seeing or completing this challenge, this page may help. If you continue to experience issues, you can contact JSTOR support. Block Reference: #7fc8aa90-cf51-11eb-a8fa-33e0b1df654c VID: #(null) IP: 116.202.236.252 Date and time: Thu, 17 Jun 2021 09:50:50 GMT. Benjamin Henry Latrobe. Benjamin Henry Latrobe was born in 1764 at Fulneck in Yorkshire. He was the Second son of the Reverend Benjamin Latrobe (1728 - 86), a minister of the Moravian church, and Anna Margaretta (Antes) Latrobe (1728 - 94), a third generation Pennsylvanian of Moravian Parentage. The original Latrobes had been French Huguenots who had settled in Ireland at the end of the 17th Century. Whilst he is most noted for his work on The White House and the Capitol in Washington, he introduced the Greek Revival as the style of American National architecture. He built Baltimore cathedral, not only the first Roman Catholic Cathedral in America but also the first vaulted church and is, perhaps, Latrobes finest monument. Hammerwood Park achieves importance as his first complete work, the first of only two in this country and one of only five remaining domestic buildings by Latrobe in existence. It was built as a temple to Apollo, dedicated as a hunting lodge to celebrate the arts and incorporating elements related to Demeter, mother Earth, in relation to the contemporary agricultural revolution. -

Robert Moses Replies to Robert Caro

We Live in a Motorized Civilization: Robert Moses Replies to Robert Caro Geoff Boeing Department of Urban Planning and Spatial Analysis University of Southern California April 2021 Introduction In 1974, Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. published Robert Caro’s The Power Broker, a critical biog- raphy of Robert Moses’s dictatorial tenure as the “master builder” of mid-century New York. Moses profoundly transformed New York’s urban fabric and transportation sys- tem, producing the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel, the Verrazano Narrows Bridge, the West- side Highway, the Cross-Bronx Expressway, the Lincoln Center, the UN headquarters, Shea Stadium, Jones Beach State Park, and many other projects. However, The Power Broker did lasting damage to his public image and today he remains one of the most con- troversial figures in city planning history. Caro’s book won the 1975 Pulitzer Prize and was eventually named one of the Modern Library’s 100 greatest nonfiction books of the twentieth century. Prior to this critical acclaim, however, came a pointed response from arXiv:2104.06179v1 [econ.GN] 26 Mar 2021 the biography’s subject. On August 26, 1974, Moses issued a turgid 23-page statement denouncing Caro’s work as “full of mistakes, unsupported charges, nasty baseless personalities, and random haymakers.” In his statement, Moses denied having had any responsibility for mass tran- sit, dismissed his “lady critics,” and defended the forced displacement of the poor as a necessary component of urban revitalization: “I raise my stein to the builder who can remove ghettos without moving people as I hail the chef who can make omelets without breaking eggs.” The statement also included a striking passage on what Moses perceived to be his critics’ hypocrisies in the modern age of automobility: “One cannot help being 1 amused by my friends among the media who shout for rails and inveigh against rubber but admit that they live in the suburbs and that their wives are absolutely dependent on motor cars. -

John Lewis Gaddis on Learning the Scholar's Craft

H-Diplo H-Diplo Essay 208- John Lewis Gaddis on Learning the Scholar’s Craft: Reflections of Historians and International Relations Scholars Discussion published by George Fujii on Friday, March 27, 2020 H-Diplo Essay 208 Essay Series on Learning the Scholar’s Craft: Reflections of Historians and International Relations Scholars 27 March 2020 Maybe You Can Go Home Again https://hdiplo.org/to/E208 Series Editor: Diane Labrosse | Production Editor: George Fujii Essay by John Lewis Gaddis, Yale University My home town in Texas has two claims to fame. Cotulla, founded in 1881 and located halfway between San Antonio and Laredo, quickly became notorious for its feuds, shootouts, and murders: it was, the El Paso Times reported five years later, “the toughest place” in the state.[1] In due course, though, it settled down, and by 1928 when the twenty year old Lyndon B. Johnson arrived to teach in its segregated “Mexican” school, Cotulla was on the way to earning its second claim—its very own chapter in Robert Caro’s epic biography.[2] It was, by then, a placid backwater. Or would have been if it had rained more often. I was born there in 1941. My parents grew up a block from one another. My brothers and I walked to school past only two houses, each occupied by relatives. Our dad’s drugstore, whose soda fountain made it the town’s social center, was three blocks in the other direction, past the telephone exchange where operators still asked, when you picked up your phone, “Number please?” None had more than three digits, and no calls came through during nap time. -

Download This Publication in PDF Format

“WHAT THE HELL’S A PRESIDENCY FOR?” Making Washington Work Revisiting H the Great SocietY THE ROLE OF GOVERNMENT FROM FDR & LBJ TO TODAY The 2012 Roosevelt House Presidential Leadership Symposium A Report and Reflection by Joseph A. Califano, Jr. Edited by Christine Zarett TABLE of Contents H PREFACE 4 ABOUT THE AUTHOR 7 INTRODUCTION 8 SYMPOSIUM DAY ONE 13 OPENING KEYNOTE ADDRESS 14 PRESIDENTIAL LEADERSHIP: MAKING WASHINGTON WORK 16 SYMPOSIUM DAY TWO 35 CIVIL RIGHTS 36 © 2012 HEALTH CARE 47 Roosevelt House Public Policy Institute at Hunter College CONCLUSION 54 47-49 East 65 Street New York, NY 10065 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 56 SYMPOSIUM SCHEDULE 57 Cover Image: President Lyndon B. Johnson and Joseph Califano, Jr., 1968. NotEs 61 H PREFACE A Message from Jennifer Raab and Jonathan Fanton On March 14-15, it was a privilege for Hunter College’s Roosevelt Joseph Califano’s essay identifies eight qualities of leadership House Public Policy Institute to host “Revisiting the Great Society: that made Lyndon Johnson so effective. Included among them The Role of Government from FDR and LBJ to Today.” Over two days, are knowing how to work with Congress, a laser focus, a zest for a distinguished roster of scholars and practitioners considered the political process, courage and good timing, and a willingness lessons learned from Roosevelt’s New Deal and Johnson’s Great to deploy the full powers of the presidency. Each is illustrated with Society with an eye toward understanding how to make Washington textured examples drawn from Joseph Califano’s direct observations work today. as part of the Johnson inner circle.