The Little Orchestra Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Decca Discography

DECCA DISCOGRAPHY >>V VIENNA, Austria, Germany, Hungary, etc. The Vienna Philharmonic was the jewel in Decca’s crown, particularly from 1956 when the engineers adopted the Sofiensaal as their favoured studio. The contract with the orchestra was secured partly by cultivating various chamber ensembles drawn from its membership. Vienna was favoured for symphonic cycles, particularly in the mid-1960s, and for German opera and operetta, including Strausses of all varieties and Solti’s “Ring” (1958-65), as well as Mackerras’s Janá ček (1976-82). Karajan recorded intermittently for Decca with the VPO from 1959-78. But apart from the New Year concerts, resumed in 2008, recording with the VPO ceased in 1998. Outside the capital there were various sessions in Salzburg from 1984-99. Germany was largely left to Decca’s partner Telefunken, though it was so overshadowed by Deutsche Grammophon and EMI Electrola that few of its products were marketed in the UK, with even those soon relegated to a cheap label. It later signed Harnoncourt and eventually became part of the competition, joining Warner Classics in 1990. Decca did venture to Bayreuth in 1951, ’53 and ’55 but wrecking tactics by Walter Legge blocked the release of several recordings for half a century. The Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra’s sessions moved from Geneva to its home town in 1963 and continued there until 1985. The exiled Philharmonia Hungarica recorded in West Germany from 1969-75. There were a few engagements with the Bavarian Radio in Munich from 1977- 82, but the first substantial contract with a German symphony orchestra did not come until 1982. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 109, 1989-1990, Subscription

BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SBJI OZAWA MUSIC DIRECTOR 109TH SEASON 1989-90 ^r^ After the show, enjoy the limelight. Tanqueray. A singular experience. Imported English Gin, 47.3% Alc/Vol (94.6°). 100% Grain Neutral Spirits. © 1988 Schieffelin & Somerset Co., New York, N.Y. Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Carl St. Clair and Pascal Verrot, Assistant Conductors One Hundred and Ninth Season, 1989-90 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Nelson J. Darling, Jr., Chairman Emeritus J. P. Barger, Chairman George H. Kidder, President Mrs. Lewis S. Dabney, Vice-Chairman Archie C. Epps, Vice-Chairman Mrs. John H. Fitzpatrick, Vice-Chairman William J. Poorvu, Vice-Chairman and Treasurer David B. Arnold, Jr. Mrs. Eugene B. Doggett Mrs. August R. Meyer Peter A. Brooke Avram J. Goldberg Mrs. Robert B. Newman James F. Geary Mrs. John L. Grandin Peter C. Read John F. Cogan, Jr. Francis W. Hatch, Jr. Richard A. Smith Julian Cohen Mrs. Bela T. Kalman Ray Stata William M. Crozier, Jr. Mrs. George I. Kaplan William F. Thompson Mrs. Michael H. Davis Harvey Chet Krentzman Nicholas T. Zervas Trustees Emeriti Vernon R. Alden Mrs. Harris Fahnestock Mrs. George R. Rowland Philip K. Allen E. Morton Jennings, Jr. Mrs. George Lee Sargent Allen G. Barry Edward M. Kennedy Sidney Stoneman Leo L. Beranek Albert L. Nickerson John Hoyt Stookey Mrs. John M. Bradley Thomas D. Perry, Jr. John L. Thorndike Abram T. Collier Irving W. Rabb Other Officers of the Corporation John Ex Rodgers, Assistant Treasurer Michael G. McDonough, Assistant Treasurer Daniel R. Gustin, Clerk Administration Kenneth Haas, Managing Director Daniel R. -

INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter 6ce, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing In this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Ifowell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 NOTE TO USERS The original manuscript received by UMI contains pages with slanted print. Pages were microfilmed as received. This reproduction is the best copy available UMI JANICE HARSANYI; PROFILE OF AN ARTISTATEACHER D.M.A. -

Mahler Symphony No.8

MAHLER SYMPHONY NO.8 KLAUS TENNSTEDTconductor LONDON PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA A BBC recording 0052 Mahler 8 booklet 20 page version.indd 1 11/01/2011 10:06:37 MAHLER SYMPHONY NO.8 Mahler composed his Eighth Symphony at scherzo and finale. And since Faust’s his lakeside summer home in Carinthia in aspirations towards superhuman wisdom 1906. His wife Alma, to whom he dedicated paralleled the Catholics’ invocation of the the work, remembered that time as their ‘last Holy Spirit, it was logical as well as musically summer of peace and beauty and content’. unifying to develop themes from Part I in Part The following year they suffered three II. The first draft was finished in eight weeks, grievous blows: the loss of Mahler’s musical and Mahler wrote to the conductor Willem directorship of the Vienna Court Opera, the Mengelberg: ‘It is the greatest work I have death of their four-year-old elder daughter and yet composed…Imagine that the universe the diagnosis of Mahler’s heart disease. Yet bursts into song. We no longer hear human in 1906 all seemed well. The summer began voices but those of planets and suns.’ The as usual with him fearing loss of inspiration. triumphant first performance took place Then one morning there came into his mind in Munich on 12 September 1910. Eight the words of Veni, Creator Spiritus (Come, months later Mahler died, burnt out at fifty. Creator Spirit), the 9th-century Catholic hymn for Pentecost. He started setting the In his handling of the huge forces Mahler lines to music, beginning what developed integrates the eight solo voices and three into the work that a German impresario choirs into complex orchestral textures nicknamed with pardonable exaggeration the with scant regard for the singers’ comfort. -

The Flute in Opera

The New York Flute Club N E W S L E T T E R March 2004 The Flute in Opera: Three Inside Views Interview by Katherine Fink his interview reflects the fascinating differences between our first chair opera flutists, not only in the way they think about their careers, but also in the way the interviews were conducted. Michael Parloff responded by email in a rich and elo- Tquent narrative, Trudy Kane invited me to her home and fed me a delicious brunch, and Bart Feller gave a phone inter- view. The hardest part for me was to condense three fantastic commentaries into one. I encourage you to seek out these artists at the Flute Fair to hear more of their highly entertaining anecdotes. KF: Trudy and Michael, how old were you when you got the job at the Met? Did you encounter difficulties because of your youth? MP: I was 24 when I joined the Met Orchestra in 1977. At that time the flute BART FELLER TRUDY KANE MICHAEL PARLOFF section had recently been transformed from four men with an average age of In Concert about 60 to a group of still-wet-behind- Sunday, March 14, 2004, 5:45 pm the-ears twenty-somethings. Undoubt- edly, it was strange for some of the older LaGuardia Concert Hall members of the orchestra to have young LaGuardia High School of Music and Art and Performing Arts men and, particularly, young women 100 Amsterdam Avenue (at 65th Street) heading up their sections. Interestingly, some of the “youngsters” from the class Program of ’77 have already started to retire. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 99, 1979-1980

H^l eleven 99th SEASON *^«?s &%^ >) BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SEIJI OZAWA Music Director — ^ <f mm V.S.O.t* 11 <s$Utt&>ft&ndm enf7%r mvH^ 6' £0. V&QP COGNAC FRANCE ***&£''* ISO ifcitoiSOTTLKO HY F BPMV MARTIN NE CHAMPAGNE COGW THE FIRST NAME IN COGNAC SINCE 172 FINE CHAMPAGNE COGNAC: FROM QUALITY: A DISTINGUISHING ATTRIBUTE State Street Bank and Trust Company unites you to an evening with The Boston Symphon) Orchestra every Friday at nine on WCRB/IM. Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Colin Davis, Principal Guest Conductor Joseph Silverstein, Assistant Conductor Ninety-Ninth Season 1979-80 The Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra Inc. Talcott M. Banks, Chairman Nelson J. Darling, Jr., President Philip K. Allen, Vice-President Sidney Stoneman, Vice-President Mrs. Harris Fahnestock, Vice-President John L. Thorndike, Vice-President Roderick M. MacDougall, Treasurer Vernon R. Alden Archie C. Epps III Thomas D. Perry, Jr. Allen G. Barry E. Morton Jennings, Jr. Irving W. Rabb LeoL. Beranek Edward M. Kennedy Paul C. Reardon Mrs. John M. Bradley George H. Kidder David Rockefeller, Jr. George H.A. Clowes, Jr. Edward G. Murray Mrs. George Lee Sargent Abram T. Collier Albert L. Nickerson John Hoyt Stookey Trustees Emeriti Richard P. Chapman John T. Noonan Mrs. James H. Perkins Administration of the Boston Symphony Orchestra Thomas W. Morris General Manager Peter Gelb Gideon Toeplitz Daniel R. Gustin Assistant Manager Orchestra Manager Assistant Manager Joseph M. Hobbs Walter D.Hill William Bernell Director of Director of Assistant to the Development Business Affairs General Manager Lawrence Murray Dorothy Sullivan Anita R. -

The Operatic Bassoon: a Pedagogical Excerpt Collection

!"#$%&#'(!)*$+(,,%%-.$($&#/(0%0)*(1$#2*#'&!$*%11#*!)%-$ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ 34$ $ ,565$(7$869:;:$ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ ,93<=>>:?$>@$>;:$A5B9C>4$@A$>;:$ D5B@3E$,B;@@C$@A$F9E=B$=G$H56>=5C$A9CA=CC<:G>$ @A$>;:$6:I9=6:<:G>E$A@6$>;:$?:J6::K$ /@B>@6$@A$F9E=B$ )G?=5G5$LG=M:6E=>4$ F54$NONP$ $ $ (BB:H>:?$34$>;:$A5B9C>4$@A$>;:$ )G?=5G5$LG=M:6E=>4$D5B@3E$,B;@@C$@A$F9E=BK$ =G$H56>=5C$A9CA=CC<:G>$@A$>;:$6:I9=6:<:G>E$A@6$>;:$?:J6::$ /@B>@6$@A$F9E=B$ $ $ /@B>@65C$*@<<=>>::$$ $ $ $ QQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQ$ R=CC=5<$19?S=JK$':E:56B;$/=6:B>@6$T$*;5=6$ $ $ $ $ QQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQ$ U5>;64G$19V5E$ $ $ $ $ QQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQ$ U5>;C::G$FB1:5G$ $ $ $ $ QQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQ$ &:>:6$F=VEW5$ $ $ (H6=C$NPK$NONP$ $ $ ==$ $ *@H46=J;>$X$NONP$ ,565$869:;:$ $ $ ===$ $ $ !"#$%#&'()#*'+),(-.#/0$0#',1#2)+$',.## 34"#(""5#$)#("#)6)+%#$7-08#&)--",.#%"7(4#"+84)-(+'#+)4)'+-'&.#',1#'((),1)1#)6)+%#*"--09&)#8",8)+(:## ;40&)#,"#&",<)+#4)+).#0(#0-#%"7+#6"08)-#',1#9)&0)=#0,#$)#(4'(#8",(0,7)#("#-))#$)#(4+"7<4:# >#'$#(4)#3"$',#>#'$#("1'%#9)8'7-)#"=#%"7:# ?"6)#',1#$0--#%"7:# @&3'%-:# # # : =M$ $ !"#$%&'()*(+($,-. !;5GV$4@9$>@$>;:$<5G4$@H:65$@6J5G=W5>=@GE$5G?$A:CC@S$35EE@@G=E>E$S;@$S=CC=GJC4$5=?:?$<4$ 6:E:56B;$=G$H6@M=?=GJ$@H:65$59?=>=@G$6:H:6>@=6:$H5BV:>E$5G?$C=E>E7$!;5GV$4@9$>@$+@@E:4$T$"5SV:EK$1>?7$ A@6$6:H6=G>$H:6<=EE=@GE$@A$!4)#A'5)B-#C+"<+)--#5G?$C)()+#D+0$)-7$$ !;5GV$4@9$>@$<4$B@CC:5J9:E$5G?$A6=:G?E$5>$)G?=5G5$LG=M:6E=>4$S;@$;5M:$3::G$9G?:6E>5G?=GJ$5G?$ E9HH@6>=M:$@A$<4$:G?:5M@6E$>@$B@<HC:>:$>;=E$?@B9<:G>$5G?$?:J6::$S;=C:$S@6V=GJ$A9CCY>=<:K$5G?$>;:G$ -

NYP 20-01 RELEASE DATE: September 25, 2019

THE NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC THIS WEEK Broadcast Schedule – Fall 2019 PROGRAM#: NYP 20-01 RELEASE DATE: September 25, 2019 Bernstein conducts Haydn’s Mass in B-flat STRAUSS: Also sprach Zarathustra Guiseppe Sinopoli, conductor HAYDN: Mass in B‐flat, Hob. XXII:14 Judith Blegen, soprano Frederica Von Stade, mezzo Kenneth Riegel, tenor Simon Estes, bass Westminster Choir Joseph Flummerfelt, director Leonard Bernstein, conductor STRAUSS: Tod und Verklärung, Op. 24 Giuseppe Sinopoli, conductor PROGRAM#: NYP 20-02 RELEASE DATE: October 2, 2019 Boulez and Bernstein conduct Dukas, Beethoven, Roussel, and Ravel DUKAS: La Péri (fanfare et poème danse) Pierre Boulez, conductor BEETHOVEN: Piano Concerto No. 1 in C Major, Op. 15 Leonard Bernstein, piano & conductor ROUSSEL: Symphony No. 3 in G minor, Op. 42 Pierre Boulez, conductor RAVEL: Mother Goose (Ma Mére l’oye) Pierre Boulez, conductor PROGRAM#: NYP 20-03 RELEASE DATE: October 9, 2019 Masur conducts Missa Solemnis PROKOFIEV: Symphony No. 1, Op. 25 “Classical” Leonard Bernstein, conductor MENDELSSOHN: Violin Concerto in E Minor, Op. 64 Nathan Milstein, violin Bruno Walter, conductor BEETHOVEN: Mass in D Major, Op. 123, “Missa solemnis” Christine Brewer, soprano Florence Quivar, mezzo Anthony Rolfe Johnson, tenor Peter Rose, bass Glenn Dicterow, violin New York Choral Artists, dir. Joseph Flummerfelt American Boychoir, dir. James Litton Kurt Masur, conductor PROGRAM#: NYP 20-04 RELEASE DATE: October 16, 2019 Wind Concertos and More VIVALDI: Concerto for Piccolo, Strings, and Cembalo in C Major, RV. 444 Mindy Kaufmann, piccolo Zubin Mehta, conductor HINDEMITH: Symphony: “Mathis der Maler” Leonard Bernstein, conductor MOZART: Concerto for Bassoon and Orchestra in B‐flat Major, K. -

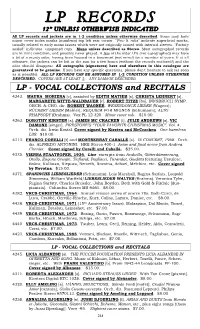

LP RECORDS 12” UNLESS OTHERWISE INDICATED All LP Records and Jackets Are in 1-2 Condition Unless Otherwise Described

LP RECORDS 12” UNLESS OTHERWISE INDICATED All LP records and jackets are in 1-2 condition unless otherwise described. Some may have minor cover index marks (numbers) top left rear corner. "Few lt. rubs" indicate superficial marks, usually related to early mono issues which were not originally issued with internal sleeves. "Factory sealed" indicates unopened copy. Mono unless described as Stereo. Most autographed records are in mint condition, and possibly never played. A few of the older LPs (not autographed) may have a bit of a musty odor, having been housed in a basement (not mine!) for a number of years. If at all offensive, the jackets can be left in the sun for a few hours (without the records enclosed!) and the odor should disappear. All autographs (signatures) here and elsewhere in this catalogue are guaranteed to be genuine. If you have any specific questions, please don’t hesitate to ask (as soon as is possible). ALL LP RECORDS CAN BE ASSUMED IN 1-2 CONDITION UNLESS OTHERWISE DESCRIBED. COVERS ARE AT LEAST 2. ANY DAMAGE DESCRIBED. LP - VOCAL COLLECTIONS and RECITALS 4243. MAURA MORIERA [c], assisted by EDITH MATHIS [s], CHRISTA LEHNERT [s], MARGARETE WITTE-WALDBAUER [c], ROBERT TITZE [bs], INNSBRUCH SYMP. ORCH. & CHO. dir. ROBERT WAGNER. WESENDONCK LIEDER (Wagner); RÜCKERT LIEDER (Mahler); REQUIEM FOR MIGNON (Schumann); ALTO RHAPSODY (Brahms). Vox PL 12.320. Minor cover rub. $10.00. 4263. DOROTHY KIRSTEN [s], JAMES MC CRACKEN [t], JULIE ANDREWS [s], VIC DAMONE [singer]. FIRESTONE’S “YOUR FAVORITE CHRISTMAS MUSIC”. Vol. 4. Orch. dir. Irwin Kostal. Cover signed by Kirsten and McCracken. -

Mcgill Community for Lifelong Learning | Rory O'sullivan Music

Rory O’Sullivan Opera and Music DVD Collection McGill Community for Lifelong Learning McGill Community for Lifelong Learning | Rory O’Sullivan Music Collection Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................ 3 Borrowing Procedure ................................................................................................. 4 DVD Request Form ................................................................................................... 5 Opera Collection ........................................................................................................ 6 Opera Compilations ...............................................................................................263 Orchestral and Other Works ..................................................................................287 Last Update: 28 March 2017 Page 2 McGill Community for Lifelong Learning | Rory O’Sullivan Music Collection Introduction McGill Community for Lifelong Learning is now in possession of a unique collection of opera DVDs. The family of the late Rory O’Sullivan has generously donated his personal collection for the pleasure and enjoyment of all MCLL members. Rory, through his very popular and legendary Opera Study Groups, inspired huge numbers with his knowledge, love and passion for opera. An architect by profession, Rory was born, raised and educated in Ireland. In his youth he participated in school productions of Gilbert and Sullivan operettas. This instilled -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 103, 1983-1984

oston Symphony Orchestra SEIJI OZAWA, Music Director .* ' BOSTON % /symphony \ \ orchestra/ . iV SEIJI OZAWA >:- 103rd Season 1983-84 Imported by Remy Martin Amerique, Inc., N.Y VS.O.P COGNAC. SINCE 1 Sole U.S.A. Distributor, Premiere Wine Merchants Inc., N.Y. 80 Proof. REMY MARTIN* Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Sir Colin Davis, Principal Guest Conductor Joseph Silverstein, Assistant Conductor One Hundred and Third Season, 1983-84 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Leo L. Beranek, Chairman Nelson J. Darling, Jr., President Mrs. Harris Fahnestock, Vice-President George H. Kidder, Vice-President Sidney Stoneman, Vice-President Roderick M. MacDougall, Treasurer John Ex Rodgers, Assistant Treasurer Vernon R. Alden Archie C. Epps HI Thomas D. Perry, Jr. David B. Arnold, Jr. Mrs. John H. Fitzpatrick William J. Poorvu J. P. Barger Mrs. John L. Grandin Irving W. Rabb Mrs. John M. Bradley E. James Morton Mrs. George R. Rowland Mrs. Norman L. Cahners David G. Mugar Mrs. George Lee Sargent George H.A. Clowes, Jr. Albert L. Nickerson William A. Selke Mrs. Lewis S. Dabney John Hoyt Stookey Trustees Emeriti Abram T. Collier, Chairman ofthe Board Emeritus Philip K. Allen E. Morton Jennings, Jr. Mrs. James H. Perkins Allen G. Barry Edward M. Kennedy Paul C. Reardon Richard P. Chapman Edward G. Murray John L. Thorndike John T. Noonan Administration of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Thomas W. Morris - General Manager William Bernell - Artistic Administrator Daniel R. Gustin - Assistant Manager B.J. Krintzman - Director ofPlanning Anne H. Parsons - Orchestra Manager Caroline Smedvig - Director ofPromotion Josiah Stevenson - Director ofDevelopment Theodore A. -

Beverly, “Music Misses You”

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2014 BEVERLY, “MUSIC MISSES YOU”: A BIOGRAPHICAL AND PERFORMANCE GUIDE TO AMERICAN MEZZO-SOPRANO BEVERLY WOLFF’S CAREER AND HER SUBSEQUENT IMPACT ON AMERICAN OPERA AND ART SONG Sarah C. Downs Trail University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Downs Trail, Sarah C., "BEVERLY, “MUSIC MISSES YOU”: A BIOGRAPHICAL AND PERFORMANCE GUIDE TO AMERICAN MEZZO-SOPRANO BEVERLY WOLFF’S CAREER AND HER SUBSEQUENT IMPACT ON AMERICAN OPERA AND ART SONG" (2014). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 27. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/27 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known.