Assessment of the Mary River Project: Impacts and Benefits

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Figure 5: Arctic Bay and Clyde River Site-Specific Marine Hunting Values Reported in the Study Area

FINAL REPORT: QIA’S TUSAQTAVUT STUDY SPECIFIC TO BAFFINLAND’S PROPOSED PHASE 2 OF THE MARY RIVER PROJECT FOR THE COMMUNITIES OF ARCTIC BAY AND CLYDE RIVER Figure 5: Arctic Bay and Clyde River site-specific Marine Hunting values reported in the Study Area 37 FINAL REPORT: QIA’S TUSAQTAVUT STUDY SPECIFIC TO BAFFINLAND’S PROPOSED PHASE 2 OF THE MARY RIVER PROJECT FOR THE COMMUNITIES OF ARCTIC BAY AND CLYDE RIVER 4.2.2 Importance Marine Hunting encompasses a variety of species, bodies of knowledge, modes of travel, animal processing and food storage techniques (e.g., food caches), and harvesting locations and habitation sites. Study participants have used and continue to use the Study Area for Marine Hunting. The quotes below highlight some of their experiences hunting narwhal, walrus, and seal species in and around Milne Inlet, Eclipse Sound, Pond Inlet, and Baffin Bay. So, his family would also go narwhal hunting around Milne Inlet. … Yeah, that was a prime narwhal hunting area all that along here. … Yeah, that whole area. (C15 2020a, interpreted from Inuktitut) There was so much narwhal that you could hear them as soon as you wake up and they’d be there all day … They’re migrating but there’s so many of them that they would – it could take all day into the night, that’s how much narwhal there was … So they … would do all their narwhal hunting around that area [in Eclipse Sound]. (A01 2020, interpreted from Inuktitut) Plenty of seal hunting around Mount Herodier area. … And then, you know, he would also remember people catching narwhal really close to Pond Inlet when he was a child, but he can’t quite pinpoint what the year was. -

RECLAMATION PILOT STUDY Mary River Mine Project

RECLAMATION PILOT STUDY Mary River Mine Project Revegetaon Survey & Preliminary Reclamaon Trial REV.1 Prepared For Baffinland Iron Mines Corporaon 300 - 2275 Upper Middle Road East Oakville, ON L6H 0C3 Prepared By EDI Environmental Dynamics Inc. 220 - 736, 8 Ave. Southwest Calgary, AB T2P 1H4 EDI Contact Patrick Audet, PhD, RPBio Mike Seerington, MSc, RPBio EDI Project 19Y0005:2008 March 2020 Down to Earth Biology This page is intentionally blank. RECLAMATION PILOT STUDY Mary River Mine Project | Revegetation Survey & Preliminary Reclamation Trial TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................... 1 2 POST-DISTURBANCE REVEGETATION SURVEY............................................................................................ 2 2.1 SURVEY DESIGN ........................................................................................................................................................................... 2 2.2 METHODS & ANALYSES ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 2.3 RESULTS SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................................................................... 6 2.3.1 KM52 — 1-Year Post-Disturbance ........................................................................................................................................ -

Canadian Arctic Tide Measurement Techniques and Results

International Hydrographie Review, Monaco, LXIII (2), July 1986 CANADIAN ARCTIC TIDE MEASUREMENT TECHNIQUES AND RESULTS by B.J. TAIT, S.T. GRANT, D. St.-JACQUES and F. STEPHENSON (*) ABSTRACT About 10 years ago the Canadian Hydrographic Service recognized the need for a planned approach to completing tide and current surveys of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago in order to meet the requirements of marine shipping and construction industries as well as the needs of environmental studies related to resource development. Therefore, a program of tidal surveys was begun which has resulted in a data base of tidal records covering most of the Archipelago. In this paper the problems faced by tidal surveyors and others working in the harsh Arctic environment are described and the variety of equipment and techniques developed for short, medium and long-term deployments are reported. The tidal characteris tics throughout the Archipelago, determined primarily from these surveys, are briefly summarized. It was also recognized that there would be a need for real time tidal data by engineers, surveyors and mariners. Since the existing permanent tide gauges in the Arctic do not have this capability, a project was started in the early 1980’s to develop and construct a new permanent gauging system. The first of these gauges was constructed during the summer of 1985 and is described. INTRODUCTION The Canadian Arctic Archipelago shown in Figure 1 is a large group of islands north of the mainland of Canada bounded on the west by the Beaufort Sea, on the north by the Arctic Ocean and on the east by Davis Strait, Baffin Bay and Greenland and split through the middle by Parry Channel which constitutes most of the famous North West Passage. -

Caribou (Barren-Ground Population) Rangifer Tarandus

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Caribou Rangifer tarandus Barren-ground population in Canada THREATENED 2016 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2016. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Caribou Rangifer tarandus, Barren-ground population, in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. xiii + 123 pp. (http://www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/default.asp?lang=en&n=24F7211B-1). Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Anne Gunn, Kim Poole, and Don Russell for writing the status report on Caribou (Rangifer tarandus), Barren-ground population, in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada. This report was overseen and edited by Justina Ray, Co-chair of the COSEWIC Terrestrial Mammals Specialist Subcommittee, with the support of the members of the Terrestrial Mammals Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment and Climate Change Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-938-4125 Fax: 819-938-3984 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur le Caribou (Rangifer tarandus), population de la toundra, au Canada. Cover illustration/photo: Caribou — Photo by A. Gunn. Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2016. Catalogue No. CW69-14/746-2017E-PDF ISBN 978-0-660-07782-6 COSEWIC Assessment Summary Assessment Summary – November 2016 Common name Caribou - Barren-ground population Scientific name Rangifer tarandus Status Threatened Reason for designation Members of this population give birth on the open arctic tundra, and most subpopulations (herds) winter in vast subarctic forests. -

Approaching Economic Growth and Sustainable Communities in Context of Mining in Nunavut

Mining a Better Future: Approaching Economic Growth and Sustainable Communities in Context of Mining in Nunavut by Nadav Goelman B.A. (Professional Communications), Royal Roads University, 2010 Capstone Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Public Policy in the School of Public Policy Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Nadav Goelman 2014 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2014 Approval Name: Nadav Goelman Degree: Master of Public Policy Title of Thesis: Mining a Better Future: Approaching Economic Growth and Sustainable Communities in Context of Mining in Nunavut Examining Committee: Chair: Dominique M. Gross Professor, School of Public Policy, SFU Nancy Olewiler Senior Supervisor Professor Doug McArthur Supervisor Professor Maureen Maloney Internal Examiner Professor School of Public Policy Date Defended/Approved: March 5, 2014 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii Ethics Statement iv Abstract Resource development near isolated communities in Nunavut exacerbates preexisting social problems that are insufficiently ameliorated by the policy frameworks addressing them. Data from Baker Lake shows rising crime rates correlating with the mine’s arrival; and failure to ameliorate stagnant, declining education outcomes. The current framework of policy is comprised of loosely coordinated efforts by the federal and territorial governments. Supplemental community-driven research was found to identify additional interventions that garner renewed local support and heightened efficacy. Economic modeling of estimated costs and benefits of these interventions within three alternatives: a local, regional, or territorial rollout, revealed plausible net benefits at various discount rates. Additional qualitative evidence of pros and cons for each alternative supported recommendation of up to three local pilot project(s) to assess efficacy of these interventions to mitigate, ameliorate, and prevent the negative side effects of resource development in Nunavut, and remove barriers to equitable sustainable economic growth. -

Draft Nunavut Land Use Plan

Draft Nunavut Land Use Plan Options and Recommendations Draft – 2014 Contents Introduction .............................................................................. 3 Aerodromes ................................................................................ 75 Purpose ........................................................................................... 3 DND Establishments ............................................................... 76 Guiding Policies, Objectives and Goals ............................... 3 North Warning System Sites................................................ 76 Considered Information ............................................................ 3 Encouraging Sustainable Economic Development ..... 77 Decision making framework .................................................... 4 Mineral Potential ...................................................................... 77 General Options Considered .................................................... 4 Oil and Gas Exploration .......................................................... 78 Protecting and Sustaining the Environment .................. 5 Commercial Fisheries .............................................................. 78 Key Migratory Bird Habitat Sites .......................................... 5 Mixed Use ............................................................................... 80 Caribou Habitat ......................................................................... 41 Mixed Use .................................................................................. -

Gjoa Haven © Nunavut Tourism

NUNAVUT COASTAL RESOURCE INVENTORY ᐊᕙᑎᓕᕆᔨᒃᑯᑦ Department of Environment Avatiliqiyikkut Ministère de l’Environnement Gjoa Haven © Nunavut Tourism ᐊᕙᑎᓕᕆᔨᒃᑯᑦ Department of Environment Avatiliqiyikkut NUNAVUT COASTAL RESOURCE INVENTORY • Gjoa Haven INVENTORY RESOURCE COASTAL NUNAVUT Ministère de l’Environnement Nunavut Coastal Resource Inventory – Gjoa Haven 2011 Department of Environment Fisheries and Sealing Division Box 1000 Station 1310 Iqaluit, Nunavut, X0A 0H0 GJOA HAVEN Inventory deliverables include: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • A final report summarizing all of the activities This report is derived from the Hamlet of Gjoa Haven undertaken as part of this project; and represents one component of the Nunavut Coastal Resource Inventory (NCRI). “Coastal inventory”, as used • Provision of the coastal resource inventory in a GIS here, refers to the collection of information on coastal database; resources and activities gained from community interviews, research, reports, maps, and other resources. This data is • Large-format resource inventory maps for the Hamlet presented in a series of maps. of Gjoa Haven, Nunavut; and Coastal resource inventories have been conducted in • Key recommendations on both the use of this study as many jurisdictions throughout Canada, notably along the well as future initiatives. Atlantic and Pacific coasts. These inventories have been used as a means of gathering reliable information on During the course of this project, Gjoa Haven was visited on coastal resources to facilitate their strategic assessment, two occasions: -

Grade 5 Module 3B, Unit 3, Lesson 3

Grade 5: Module 3B: Unit 3: Lesson 3 Conducting Research: Analyzing Expert Texts about the Mary River Project This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. Exempt third-party content is indicated by the footer: © (name of copyright holder). Used by permission and not subject to Creative Commons license. GRADE 5: MODULE 3B: UNIT 3: LESSON 3 Conducting Research: Analyzing Expert Texts about the Mary River Project Long-Term Targets Addressed (Based on NYSP12 ELA CCLS) I can analyze multiple accounts of the same topic, noting important similarities and differences in the point of view they represent. (RI.5.6) I can explain how the author uses reasons and evidence to support particular points in a text. (RI.5.8) I can draw evidence from informational texts to support analysis, reflection, and research. (W.5.9b) I can determine the meaning of unknown words and phrases, choosing flexibly from a range of strategies. (L.5.4) Supporting Learning Targets Ongoing Assessment • I can analyze the meaning of key words and phrases, using a variety of strategies. • Vocabulary terms defined on index cards and Frayer • I can support my research, analysis, and reflection on the Mary River project by drawing upon evidence Models from expert texts. • Point of View Graphic Organizer: Expert Texts • I can explain the reasons and evidence given to support two different points of view about the Mary River project on Baffin Island. Copyright © 2013 by Expeditionary Learning, New York, NY. All Rights Reserved. NYS Common Core ELA Curriculum • G5:M3B:U3:L3 • June 2014 • 1 GRADE 5: MODULE 3B: UNIT 3: LESSON 3 Conducting Research: Analyzing Expert Texts about the Mary River Project Agenda Teaching Notes 1. -

Tab 6 Estimating the Abundance Of

SUBMISSION TO THE NUNAVUT WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT BOARD FOR Information: X Decision: Issue: South Baffin Island Caribou Abundance Survey, 2012 and Proposed Management Recommendations Background: Caribou are a critical component of the boreal and arctic ecosystems. They are culturally significant to local communities and provide an important source of food. In some areas, there is still uncertainty on population trends because of the lack of scientific information due to difficult logistics and remoteness. This is particularly true for Baffin Island, where three sub-populations of Barrenground caribou (Rangifer tarandus groenlandicus) are hypothesized, though little is known about their abundance and trends over time (Ferguson and Gauthier 1992). In the past 60 years, only discrete portions of their range have been surveyed and no robust quantitative estimates at the sub-population level were ever derived. For over a decade Inuit from communities on northern Baffin Island, and more recently from across the entire island, have reported declines in caribou numbers, although no quantitative estimates are available. In total 10 communities, representing half of all Nunavummiut, traditionally or currently harvest Baffin Island caribou. At the same time, climate change, including increased arctic temperatures and precipitation, and anthropogenic activities connected to mineral exploration and mining are potentially negatively impacting caribou and their range. Due to the risk of these cumulative negative effects, and the importance of these caribou to communities, the Department of Environment undertook, in 2012, a quantitative caribou abundance aerial survey of South Baffin Island with the support of the NWMB and co- management partners. This area represents the most abundant area of caribou on Baffin Island. -

Mining, Mineral Exploration and Geoscience Contents

Overview 2020 Nunavut Mining, Mineral Exploration and Geoscience Contents 3 Land Tenure in Nunavut 30 Base Metals 6 Government of Canada 31 Diamonds 10 Government of Nunavut 3 2 Gold 16 Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated 4 4 Iron 2 0 Canada-Nunavut Geoscience Office 4 6 Inactive projects 2 4 Kitikmeot Region 4 9 Glossary 2 6 Kivalliq Region 50 Guide to Abbreviations 2 8 Qikiqtani Region 51 Index About Nunavut: Mining, Mineral Exploration and by the Canadian Securities Administrators (CSA), the regulatory Geoscience Overview 2020 body which oversees stock market and investment practices, and is intended to ensure that misleading, erroneous, or This publication is a combined effort of four partners: fraudulent information relating to mineral properties is not Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada published and promoted to investors on the stock exchanges (CIRNAC), Government of Nunavut (GN), Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated (NTI), and Canada‑Nunavut Geoscience Office overseen by the CSA. Resource estimates reported by mineral (CNGO). The intent is to capture information on exploration and exploration companies that are listed on Canadian stock mining activities in 2020 and to make this information available exchanges must be NI 43‑101 compliant. to the public and industry stakeholders. We thank the many contributors who submitted data and Acknowledgements photos for this edition. Prospectors and mining companies are This publication was written by the Mineral Resources Division welcome to submit information on their programs and photos at CIRNAC’s Nunavut Regional Office (Matthew Senkow, for inclusion in next year’s publication. Feedback and comments Alia Bigio, Samuel de Beer, Yann Bureau, Cedric Mayer, and are always appreciated. -

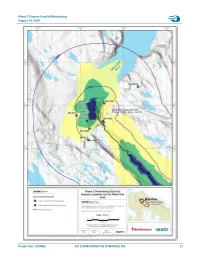

Phase 2 Passive Dustfall Monitoring August 14, 2019

Phase 2 Passive Dustfall Monitoring August 14, 2019 Project No: 19Y0006 EDI ENVIRONMENTAL DYNAMICS INC. 11 Mary River Project Phase 2 Proposal ECCC-FC1 ATTACHMENT 2: HUMAN HEALTH BASED DUSTFALL THRESHOLDS FOR MINE AND PORT SITE Date: October 15, 2019 To: Lou Kamermans, BIM From: Christine Moore, Intrinsik cc : Mike Setterington, EDI; Mike Lepage, RWDI, Richard Cook, KP; Sara Wallace and Dan Jarratt, Stantec Re: Human Health Based Dustfall Thresholds for Mine and Port Site – DRAFT V 3 While dustfall guidelines exist in several jurisdictions (such as Ontario and Alberta), they are generally based on soiling, as opposed to human health considerations. The Government of Nunavut is requesting that Project-specific dustfall guidelines protective of human health be developed for use within the Air Quality and Noise Abatement Management Plan (AQNAMP) to define rates which would be associated with management actions. Project-specific dustfall guidelines developed for consideration of human health within the Project area need to consider the model predictions for dustfall, in addition to the size of affected areas and potential exposure that could occur based on consumption rates for resources harvested within the area. These factors were used to define potential exposure scenarios. An additional consideration when developing dustfall rates protective of human health is the different geochemistry at the mine and port areas based on the existing site-specific geochemistry of the dustfall samples previously collected. As all rock and soil contain naturally occurring metals and metalloids (which will be referred to as metals), the dustfall generated from Project activities also contains metals. Iron is the most common metal in the dustfall, representing 4.43% of total dustfall at the Mine site, and 3.03% at the Port site. -

Community Experiences of Mining in Baker Lake, Nunavut

Community Experiences of Mining in Baker Lake, Nunavut by Kelsey Peterson A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Geography Guelph, Ontario, Canada ©Kelsey Peterson, April, 2012 ABSTRACT COMMUNITY EXPERIENCES OF MINING IN BAKER LAKE, NUNAVUT Kelsey Peterson Advisor: University of Guelph, 2012 Professor Ben Bradshaw With recent increases in mineral prices, the Canadian Arctic has experienced a dramatic upswing in mining development. With the development of the Meadowbank gold mine, the nearby Hamlet of Baker Lake, Nunavut is experiencing these changes firsthand. In response to an invitation from the Hamlet of Baker Lake, this research document residents’ experiences with the Meadowbank mine. These experiences are not felt homogeneously across the community; indeed, residents’ experiences with mining have been mixed. Beyond this core finding, the research suggests four further notable insights: employment has provided the opportunity for people to elevate themselves out of welfare/social assistance; education has become more common, but some students are leaving high school to pursue mine work; and local businesses are benefiting from mining contracts, but this is limited to those companies pre-existing the mine. Finally, varied individual experiences are in part generated by an individual’s context including personal context and choices. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the support and assistance of several key people. My advisor, Ben Bradshaw, has been instrumental in all stages of pre- research, research and writing. From accepting me to the program and connecting me to Baker Lake to funding my research and reading innumerable drafts of the written thesis, Professor Bradshaw has been critical to this research project.