Socio-Economic Monitoring Report for the Mary River Project | Page Ii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RECLAMATION PILOT STUDY Mary River Mine Project

RECLAMATION PILOT STUDY Mary River Mine Project Revegetaon Survey & Preliminary Reclamaon Trial REV.1 Prepared For Baffinland Iron Mines Corporaon 300 - 2275 Upper Middle Road East Oakville, ON L6H 0C3 Prepared By EDI Environmental Dynamics Inc. 220 - 736, 8 Ave. Southwest Calgary, AB T2P 1H4 EDI Contact Patrick Audet, PhD, RPBio Mike Seerington, MSc, RPBio EDI Project 19Y0005:2008 March 2020 Down to Earth Biology This page is intentionally blank. RECLAMATION PILOT STUDY Mary River Mine Project | Revegetation Survey & Preliminary Reclamation Trial TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................... 1 2 POST-DISTURBANCE REVEGETATION SURVEY............................................................................................ 2 2.1 SURVEY DESIGN ........................................................................................................................................................................... 2 2.2 METHODS & ANALYSES ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 2.3 RESULTS SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................................................................... 6 2.3.1 KM52 — 1-Year Post-Disturbance ........................................................................................................................................ -

Gjoa Haven © Nunavut Tourism

NUNAVUT COASTAL RESOURCE INVENTORY ᐊᕙᑎᓕᕆᔨᒃᑯᑦ Department of Environment Avatiliqiyikkut Ministère de l’Environnement Gjoa Haven © Nunavut Tourism ᐊᕙᑎᓕᕆᔨᒃᑯᑦ Department of Environment Avatiliqiyikkut NUNAVUT COASTAL RESOURCE INVENTORY • Gjoa Haven INVENTORY RESOURCE COASTAL NUNAVUT Ministère de l’Environnement Nunavut Coastal Resource Inventory – Gjoa Haven 2011 Department of Environment Fisheries and Sealing Division Box 1000 Station 1310 Iqaluit, Nunavut, X0A 0H0 GJOA HAVEN Inventory deliverables include: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • A final report summarizing all of the activities This report is derived from the Hamlet of Gjoa Haven undertaken as part of this project; and represents one component of the Nunavut Coastal Resource Inventory (NCRI). “Coastal inventory”, as used • Provision of the coastal resource inventory in a GIS here, refers to the collection of information on coastal database; resources and activities gained from community interviews, research, reports, maps, and other resources. This data is • Large-format resource inventory maps for the Hamlet presented in a series of maps. of Gjoa Haven, Nunavut; and Coastal resource inventories have been conducted in • Key recommendations on both the use of this study as many jurisdictions throughout Canada, notably along the well as future initiatives. Atlantic and Pacific coasts. These inventories have been used as a means of gathering reliable information on During the course of this project, Gjoa Haven was visited on coastal resources to facilitate their strategic assessment, two occasions: -

Grade 5 Module 3B, Unit 3, Lesson 3

Grade 5: Module 3B: Unit 3: Lesson 3 Conducting Research: Analyzing Expert Texts about the Mary River Project This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. Exempt third-party content is indicated by the footer: © (name of copyright holder). Used by permission and not subject to Creative Commons license. GRADE 5: MODULE 3B: UNIT 3: LESSON 3 Conducting Research: Analyzing Expert Texts about the Mary River Project Long-Term Targets Addressed (Based on NYSP12 ELA CCLS) I can analyze multiple accounts of the same topic, noting important similarities and differences in the point of view they represent. (RI.5.6) I can explain how the author uses reasons and evidence to support particular points in a text. (RI.5.8) I can draw evidence from informational texts to support analysis, reflection, and research. (W.5.9b) I can determine the meaning of unknown words and phrases, choosing flexibly from a range of strategies. (L.5.4) Supporting Learning Targets Ongoing Assessment • I can analyze the meaning of key words and phrases, using a variety of strategies. • Vocabulary terms defined on index cards and Frayer • I can support my research, analysis, and reflection on the Mary River project by drawing upon evidence Models from expert texts. • Point of View Graphic Organizer: Expert Texts • I can explain the reasons and evidence given to support two different points of view about the Mary River project on Baffin Island. Copyright © 2013 by Expeditionary Learning, New York, NY. All Rights Reserved. NYS Common Core ELA Curriculum • G5:M3B:U3:L3 • June 2014 • 1 GRADE 5: MODULE 3B: UNIT 3: LESSON 3 Conducting Research: Analyzing Expert Texts about the Mary River Project Agenda Teaching Notes 1. -

Tab 6 Estimating the Abundance Of

SUBMISSION TO THE NUNAVUT WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT BOARD FOR Information: X Decision: Issue: South Baffin Island Caribou Abundance Survey, 2012 and Proposed Management Recommendations Background: Caribou are a critical component of the boreal and arctic ecosystems. They are culturally significant to local communities and provide an important source of food. In some areas, there is still uncertainty on population trends because of the lack of scientific information due to difficult logistics and remoteness. This is particularly true for Baffin Island, where three sub-populations of Barrenground caribou (Rangifer tarandus groenlandicus) are hypothesized, though little is known about their abundance and trends over time (Ferguson and Gauthier 1992). In the past 60 years, only discrete portions of their range have been surveyed and no robust quantitative estimates at the sub-population level were ever derived. For over a decade Inuit from communities on northern Baffin Island, and more recently from across the entire island, have reported declines in caribou numbers, although no quantitative estimates are available. In total 10 communities, representing half of all Nunavummiut, traditionally or currently harvest Baffin Island caribou. At the same time, climate change, including increased arctic temperatures and precipitation, and anthropogenic activities connected to mineral exploration and mining are potentially negatively impacting caribou and their range. Due to the risk of these cumulative negative effects, and the importance of these caribou to communities, the Department of Environment undertook, in 2012, a quantitative caribou abundance aerial survey of South Baffin Island with the support of the NWMB and co- management partners. This area represents the most abundant area of caribou on Baffin Island. -

Mining, Mineral Exploration and Geoscience Contents

Overview 2020 Nunavut Mining, Mineral Exploration and Geoscience Contents 3 Land Tenure in Nunavut 30 Base Metals 6 Government of Canada 31 Diamonds 10 Government of Nunavut 3 2 Gold 16 Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated 4 4 Iron 2 0 Canada-Nunavut Geoscience Office 4 6 Inactive projects 2 4 Kitikmeot Region 4 9 Glossary 2 6 Kivalliq Region 50 Guide to Abbreviations 2 8 Qikiqtani Region 51 Index About Nunavut: Mining, Mineral Exploration and by the Canadian Securities Administrators (CSA), the regulatory Geoscience Overview 2020 body which oversees stock market and investment practices, and is intended to ensure that misleading, erroneous, or This publication is a combined effort of four partners: fraudulent information relating to mineral properties is not Crown‑Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada published and promoted to investors on the stock exchanges (CIRNAC), Government of Nunavut (GN), Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated (NTI), and Canada‑Nunavut Geoscience Office overseen by the CSA. Resource estimates reported by mineral (CNGO). The intent is to capture information on exploration and exploration companies that are listed on Canadian stock mining activities in 2020 and to make this information available exchanges must be NI 43‑101 compliant. to the public and industry stakeholders. We thank the many contributors who submitted data and Acknowledgements photos for this edition. Prospectors and mining companies are This publication was written by the Mineral Resources Division welcome to submit information on their programs and photos at CIRNAC’s Nunavut Regional Office (Matthew Senkow, for inclusion in next year’s publication. Feedback and comments Alia Bigio, Samuel de Beer, Yann Bureau, Cedric Mayer, and are always appreciated. -

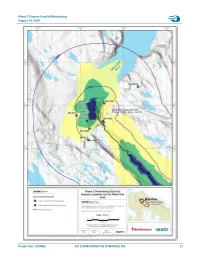

Phase 2 Passive Dustfall Monitoring August 14, 2019

Phase 2 Passive Dustfall Monitoring August 14, 2019 Project No: 19Y0006 EDI ENVIRONMENTAL DYNAMICS INC. 11 Mary River Project Phase 2 Proposal ECCC-FC1 ATTACHMENT 2: HUMAN HEALTH BASED DUSTFALL THRESHOLDS FOR MINE AND PORT SITE Date: October 15, 2019 To: Lou Kamermans, BIM From: Christine Moore, Intrinsik cc : Mike Setterington, EDI; Mike Lepage, RWDI, Richard Cook, KP; Sara Wallace and Dan Jarratt, Stantec Re: Human Health Based Dustfall Thresholds for Mine and Port Site – DRAFT V 3 While dustfall guidelines exist in several jurisdictions (such as Ontario and Alberta), they are generally based on soiling, as opposed to human health considerations. The Government of Nunavut is requesting that Project-specific dustfall guidelines protective of human health be developed for use within the Air Quality and Noise Abatement Management Plan (AQNAMP) to define rates which would be associated with management actions. Project-specific dustfall guidelines developed for consideration of human health within the Project area need to consider the model predictions for dustfall, in addition to the size of affected areas and potential exposure that could occur based on consumption rates for resources harvested within the area. These factors were used to define potential exposure scenarios. An additional consideration when developing dustfall rates protective of human health is the different geochemistry at the mine and port areas based on the existing site-specific geochemistry of the dustfall samples previously collected. As all rock and soil contain naturally occurring metals and metalloids (which will be referred to as metals), the dustfall generated from Project activities also contains metals. Iron is the most common metal in the dustfall, representing 4.43% of total dustfall at the Mine site, and 3.03% at the Port site. -

Problems with the Environmental Working Groups for the Mary River

Problems with the environmental working groups for the Mary River mine Report to the Hamlet of Clyde River and Nangmautaq Hunters and Trappers Association January 5, 2021 Dr. Warren Bernauer (Department of Environment and Geography, University of Manitoba) Dr. Glen Hostetler (Natural Resources Institute, University of Manitoba) Rowan Harris (BSc, University of British Columbia) --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Baffinland’s Mary River mine uses a flexible approach to mitigating environmental effects. The mitigation measures are not set in stone in the NIRB project certificate. Instead, Baffinland is required to regularly update its management plans, based on advice from working groups. The members of these working groups include Baffinland, government authorities, Inuit organizations, and the Miitimatalik HTO. In some cases, non-government organizations participate as observers. For example, the Marine Environment Working Group (MEWG) includes Baffinland, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Parks Canada, the Qikiqtani Inuit Association, and the Mittimatalik HTO. World Wildlife Fund and Oceans North are observers to the MEWG. The Terrestrial Environment Working Group (TEWG) includes the Government of Nunavut, QIA, and Mittimatalik HTO. When these groups were proposed, they were presented as a way to minimize the negative effects of the Mary River mine. Communities were told they could use the working groups to impose stricter mitigation measures if the mine ended up having more serious environmental impacts than expected. In other words, these working groups were supposed to provide the opportunity for adaptive management. Adaptive management is useful in situations where there is uncertainty about a project’s environmental impacts and the effectiveness of mitigation measures. It requires careful monitoring so participants can learn about the environmental impacts that are actually happening and if environmental management plans are successful in avoiding significant effects. -

Technical Report

Project N Report NI 43-101 Technical Baffin Island-Mary River, Mary RiverIron OreTrucking o . 165926 Mary River, Baffin Island, Canada Mary River Iron Ore Trucking NI 43-101 Technical Report Prepared by: AMEC Americas Ltd. Prepared for: Baffinland George H. Wahl, P. Geo Iron Mines Corporation Rene Gharapetian, P. Eng. February 2010 James E. Jackson, P. Eng Project No. 165926 Vikram Khera, P. Eng VOLUME 1 Gregory G. Wortman, P. Eng REPORT Effective Date, January 13, 2011 IMPORTANT NOTICE This report was prepared as a National Instrument 43-101 Technical Re- port for Baffinland Iron Mines Corporation (BIM) by AMEC Americas Lim- ited (AMEC). The quality of information, conclusions, and estimates con- tained herein is consistent with the level of effort involved in AMEC’s ser- vices, based on: i) information available at the time of preparation, ii) data supplied by outside sources, and iii) the assumptions, conditions, and qualifications set forth in this report. This report is intended for use by (BIM) subject to the terms and conditions of its contract with AMEC. This contract permits (BIM) to file this report as a Technical Report with Cana- dian Securities Regulatory Authorities pursuant to National Instrument 43- 101, Standards of Disclosure for Mineral Projects. Except for the purposes legislated under provincial securities law, any other uses of this report by any third party is at that party’s sole risk. Baffinland Iron Mines Corporation Mary River Baffin Island Mary River Iron Ore Trucking NI 43-101 Technical Report TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................. 1-1 1.1 Introduction and Scope of Work ...................................................................................... -

In This Issue

Northern Mining News Volume 14, No. 12 December 2020 In this December 2020 issue: Mining benefits to NWT & Nunavut – the latest numbers on jobs and spending ............. 2 Breaking news! TMAC Resources Inc. to be acquired by Agnico Eagle .............................. 3 Mountain Province improving diamond prices, exceptional diamond recovered ............. 5 Sabina reports successful 2020 exploration season at Back River ..................................... 6 Sabina Gold & Silver updates construction accomplishments ........................................... 7 NorZinc hits multiple high-grade silver and zinc intercepts in drill program ..................... 8 Osisko Metals intersects 8.6 metres grading 15% Zn+Pb at Pine Point ............................. 8 Gold Terra reports Crestaurum drilling program results .................................................... 9 Vital Metals partners with Norwegian company REEtec .................................................. 11 Nighthawk reports gold intersects at Colomac ................................................................ 12 Exploration & development news briefs .......................................................................... 14 Member news releases ..................................................................................................... 16 Industry events ................................................................................................................. 17 Presentations ................................................................................................................... -

30160105.Pdf

C S A S S C C S Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat Secrétariat canadien de consultation scientifique Research Document 2009/008 Document de recherche 2009/008 An Ecological and Oceanographical Évaluation écologique et Assessment of the Alternate Ballast océanographique de la zone Water Exchange Zone in the Hudson alternative pour l’échange des eaux Strait Region de ballast de la région du détroit d'Hudson D.B. Stewart and K.L. Howland Fisheries and Oceans Canada Central and Arctic Region, Freshwater Institute 501 University Crescent Winnipeg, Manitoba R3T 2N6 This series documents the scientific basis for the La présente série documente les fondements evaluation of aquatic resources and ecosystems scientifiques des évaluations des ressources et in Canada. As such, it addresses the issues of des écosystèmes aquatiques du Canada. Elle the day in the time frames required and the traite des problèmes courants selon les documents it contains are not intended as échéanciers dictés. Les documents qu’elle definitive statements on the subjects addressed contient ne doivent pas être considérés comme but rather as progress reports on ongoing des énoncés définitifs sur les sujets traités, mais investigations. plutôt comme des rapports d’étape sur les études en cours. Research documents are produced in the official Les documents de recherche sont publiés dans language in which they are provided to the la langue officielle utilisée dans le manuscrit Secretariat. envoyé au Secrétariat. This document is available on the Internet at: Ce document est -

Covid Concern at Mary River Presumably Infected Individual Is Isolating, Health Officials Say No Reason for Nunavummiut to Worry About Spread

ᓄᕙᒡᔪᐊᕐᓇᕐᒧᑦ ᐃᓱᒫᓘᑕᐅᔪᖅ ᓄᓘᔭᕐᓂ ᐊᐃᑦᑐᖅᓯᒪᑐᐃᓐᓇᕆᐊᓕᒃ ᐃᓄᒃ ᐅᐸᒃᑕᐅᑦᑕᐃᓕᒪᔭᕆᐊᖃᖅᐳᖅ, ᐋᓐᓂᐊᖃᕐᓇᙱᑦᑐᓕᕆᔨᒃᑯᓐᓂ ᐱᓕᕆᔨᐅᔪᑦ ᐅᖃᖅᐳᑦ ᓄᓇᕗᒻᒥᐅᑦ ᐃᓱᒫᓗᒋᐊᖃᙱᓚᑦ ᐊᐃᑦᑐᐃᓂᐅᔪᒥ Covid concern at Mary River Presumably infected individual is isolating, health officials say no reason for Nunavummiut to worry about spread Volume 76 Issue 10 MONDAY, JULY 6, 2020 $.95 (plus GST) Nunavut Happy Nunavut Day! Day festivities to be indoors What does Nunavut Day mean to you? Iqalummiut march for mental health Sanirajak planning for bowhead hunt NNSL file photo Teresina Walland, then 2, laughs with delight as she holds her balloon animal aloft during Nunavut Day cele- brations in 2017. Publication mail Contract #40012157 "Liquor and cannabis outlets are easy to establish and maintain and the black market is thriving, yet treatment centres are too expensive?" 7 71605 00200 2 – Columnist Harry Maksagak questions the territory's priorities around liquor, page 9. 2 nunavutnews.com, Monday, July 6, 2020 kNKu W?9oxJ5, N[Z/su, JMw 6, 2020 `rNs/OsCh8i3j5 tu1Z5 Wdt1Q5 tu1Z5 W?9Oxt5ti3j5 tu1Z5 kNKu W?9oxJ5, N[Z/su, JMw 6, 2020 nunavutnews.com, Monday, July 6, 2020 3 Did we get it wrong? feature news êΩËîΩÇéíÇÀîᓄ á·∆¿ÖÀî Nunavut News is committed to getting facts and names right. With that goes a commitment to acknowledge mistakes and run corrections. If you spot an error in Nunavut News/North, call (867) 979- 5990 and ask to speak to an editor, or email editor- [email protected]. We'll get a correction or clarification in as soon as we can. NEWS Briefs ᐆᒪᔫᖃᑎᒥᓂᒃ ᐆᒪᕕᖃᖅᑐᒥ ᓇᓂᔭᐅᔪᖃᖅᐳᖅ ᑲᖏᖅᖠᓂᕐᒥ ᐊᐃᕕᐅᑉ ᐅᖃᖓᓂ ᐊᐃᕕᐅᑉ ᐅᖃᖓᓂ ᖃᐅᔨᓴᖅᑕᐅᓂᖓᓂ ᐆᒪᔫᖃᑎᒥᓂᒃ ᐆᒪᕕᖃᖅᑐᒥ ᖁᐱᕐᕈᖅ ᖁᐱᕐᕆᓐᓇᖅᑐᖃᖅᐳᖅ ᑲᖏᖅᖠᓂᕐᒥ, ᐋᓐᓂᐊᖃᕐᓇᙱᑦᑐᓕᕆᔨᒃᑯᑦ ᐅᖃᐅᔾᔨᕗᑦ ᓄᓇᖃᖅᑎᐅᔪᓂ. -

Baffinland Provides Update on Mary River Blockades

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Baffinland Provides Update on Mary River Blockades Mary River, NU, February 8, 2021 – The protest at Baffinland Iron Mines Corporation’s (“Baffinland”) Mary River Project is ongoing. There are more than 700 men and women currently at the Mary River Project site in Nunavut who are impacted by the protestors’ blockading of the air strip and the tote road. The Mary River airstrip is currently closed to all regularly scheduled air traffic. Food and supply flights have been suspended, as well as employee and contractor transfers, search and rescue flights, and other North Baffin air traffic support services provided by the Mary River airstrip. Baffinland understands that requests have been made by the organizers to be recognized as a Designated Inuit Organization under the Nunavut Agreement and for a portion of the royalties payable by Baffinland under the Inuit Impact and Benefit Agreement to be paid directly to them. Baffinland hears these requests, but has no right or ability to grant them. Baffinland personnel have had numerous meetings with organizers, both at the blockades and in Pond Inlet, imploring the protestors to relocate off the airstrip and allow runway maintenance to take place and flights to resume. So far these discussions have not yielded any progress. On the evening of February 4, 2021, a group of protestors erected two blockades at the Mary River Project, one on the airstrip and one on a section of the tote road. To ensure the safety of every employee, contractor and protestor on site, the majority of operational activities have been suspended until such time as it is considered safe for them to resume.