MURRAY-THESIS.Pdf (948.0Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2013 Pitching Profiles for TV Producers Media Contacts

2013 Pitching Profiles for TV Producers Media Contacts A Cision Executive Briefing Report | January 2013 Cision Briefing Book: TV Producers Regional Cable Network | Time Warner Inc., NY 1 News, Mr. Matt Besterman, News, Executive Producer Shipping Address: 75 9Th Ave Frnt 6 DMA: New York, NY (1) New York, NY 10011-7033 MSA: New York--Northern NJ--Long Island, NY--NJ--PA MSA (1) United States of America Mailing Address: 75 9Th Ave Frnt 6 Phone: +1 (212) 691-3364 (p) New York, NY 10011-7033 Fax: +1 (212) 379-3577 (d) United States of America Email: [email protected] (p) Contact Preference: E-Mail Home Page: http://www.ny1.com Profile: Besterman serves as Executive Producer for NY 1 News. He is a good contact for PR professionals pitching the program. When asked if there is any type of story idea in particular he’s interested in receiving, Besterman replies, “We don’t really know what we might be interested in until we hear about it. But it has to relate to New Yorkers.” Besterman is interested in receiving company news and profiles, event listings, personality profiles and interviews, public appearance information, rumors and insider news, and trend stories. On deadlines, Besterman says that each program is formulated the day of its broadcast, but he prefers to books guests several days in advance. Besterman prefers to be contacted and pitched by email only. Besterman has been an executive producer at New York 1 News since November 2000. He previously worked as a producer at WRGB-TV in Albany, NY since March 1998. -

Chopped All-Stars

Press Contact: Lauren Sklar Phone: 646-336-6745; E-mail: [email protected] *High-res images, show footage, and interviews available upon request. CHOPPED ALL-STARS Season Two Judge/Host Bios Ted Allen Emmy Award winner Ted Allen is the host of Chopped, Food Network’s hit primetime culinary competition show, and the author of the upcoming cookbook “In My Kitchen: 100 Recipes and Discoveries for Passionate Cooks” debuting in May, 2012, and an earlier book, "The Food You Want to Eat: 100 Smart, Simple Recipes," both from Clarkson- Potter. Ted also has been a contributing writer to Esquire magazine since 1996. Previously, he was the food and wine specialist on the groundbreaking Bravo series Queer Eye, a judge on Food Network's Iron Chef America, and a judge on Bravo’s Top Chef. He lives in Brooklyn with his longtime partner, interior designer Barry Rice. Anne Burrell Anne Burrell has always stood out in the restaurant business for her remarkable culinary talent, bold and creative dishes, and her trademark spiky blond hair. After training at New York’s Culinary Institute of America and Italy’s Culinary Institute for Foreigners, she gained hands-on experience at notable New York restaurants including Felidia, Savoy, Lumi, and Italian Wine Merchants. Anne taught for three years at New York’s Institute of Culinary Education and served as Executive Chef at New York’s Centro Vinoteca. She stars in Food Network’s Secrets of a Restaurant Chef and Worst Cooks in America and recently competed on The Next Iron Chef: Super Chefs. In 2011, she released her first cookbook, the best-selling “Cook Like a Rock Star” (Clarkson Potter). -

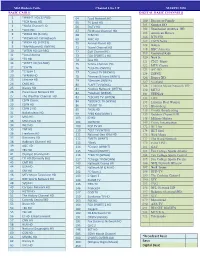

2020 March Channel Line up with Pricing Color

B is Mid-Hudson Cable Channel Line UP MARCH 2020 BASIC CABLE DIGITAL BASIC CHANNELS 2 *WMHT HD (17 PBS) 64 Food Network HD 100 Discovery Family 3 *FOX News HD 65 TV Land HD 101 Science HD 4 *NASA Channel HD 66 TruTV HD 102 Destination America HD 5 *QVC HD 67 FX Movie Channe l HD 105 American Heroes 6 *WRGB HD (6-CBS) 68 TCM HD 106 BTN HD 7 *WCWN HD CW Network 69 AMC HD 107 ESPN News 8 *WXXA HD (FOX23) 70 Animal Planet HD 108 Babytv 9 *My4AlbanyHD (WNYA) 71 Travel Channel HD 118 BBC America 10 *WTEN HD (10-ABC) 72 Golf Channel HD 119 Universal Kids 11 *Local Access 73 FOX SPORTS 1 HD 12 *FX HD 120 Nick Jr. 74 fuse HD 121 CMT Music 13 *WNYT HD (13-NBC) 75 Tennis Channel HD 122 MTV Classic 17 *EWTN 76 *LIGHTtv (WNYA) 123 IFC HD 19 *C-Span 1 77 *Comet TV (WCWN) 124 ESPNU 20 *WRNN HD 78 *Heroes & Icons (WNYT) 126 Disney XD 23 Lifetime HD 79 *Decades (WNYA) 127 Viceland 24 CNBC HD 80 *LAFF TV (WXXA) 128 Lifetime Movie Network HD 25 Disney HD 81 *Justice Network (WTEN) 130 MTV2 26 Paramount Network HD 82 *Stadium (WRGB) 131 TEENick 27 The Weather Channel HD 83 *ESCAPE TV (WTEN) 132 LIFE 28 ESPN Classic 84 *BOUNCE TV (WXXA) 133 Lifetime Real Women 29 ESPN HD 86 *START TV 135 Bloomberg 30 ESPN 2 HD 95 *HSN HD 138 Trinity Broadcasting 31 Nickelodeon HD 99 *PBS Kids(WMHT) 139 Outdoor Channel HD 32 MSG HD 103 ID HD 148 Military History 33 MSG PLUS HD 104 OWN HD 149 Crime Investigation 34 WE! HD 109 POP TV HD 172 BET her 35 TNT HD 110 *GET TV (WTEN) 174 BET Soul 36 Freeform HD 111 National Geo Wild HD 175 Nick Music 37 Discovery HD 112 *METV (WNYT) -

Friday Prime Time, April 17 4 P.M

April 17 - 23, 2009 SPANISH FORK CABLE GUIDE 9 Friday Prime Time, April 17 4 P.M. 4:30 5 P.M. 5:30 6 P.M. 6:30 7 P.M. 7:30 8 P.M. 8:30 9 P.M. 9:30 10 P.M. 10:30 11 P.M. 11:30 BASIC CABLE Oprah Winfrey Å 4 News (N) Å CBS Evening News (N) Å Entertainment Ghost Whisperer “Save Our Flashpoint “First in Line” ’ NUMB3RS “Jack of All Trades” News (N) Å (10:35) Late Show With David Late Late Show KUTV 2 News-Couric Tonight Souls” ’ Å 4 Å 4 ’ Å 4 Letterman (N) ’ 4 KJZZ 3The People’s Court (N) 4 The Insider 4 Frasier ’ 4 Friends ’ 4 Friends 5 Fortune Jeopardy! 3 Dr. Phil ’ Å 4 News (N) Å Scrubs ’ 5 Scrubs ’ 5 Entertain The Insider 4 The Ellen DeGeneres Show (N) News (N) World News- News (N) Two and a Half Wife Swap “Burroughs/Padovan- Supernanny “DeMello Family” 20/20 ’ Å 4 News (N) (10:35) Night- Access Holly- (11:36) Extra KTVX 4’ Å 3 Gibson Men 5 Hickman” (N) ’ 4 (N) ’ Å line (N) 3 wood (N) 4 (N) Å 4 News (N) Å News (N) Å News (N) Å NBC Nightly News (N) Å News (N) Å Howie Do It Howie Do It Dateline NBC A police of cer looks into the disappearance of a News (N) Å (10:35) The Tonight Show With Late Night- KSL 5 News (N) 3 (N) ’ Å (N) ’ Å Michigan woman. (N) ’ Å Jay Leno ’ Å 5 Jimmy Fallon TBS 6Raymond Friends ’ 5 Seinfeld ’ 4 Seinfeld ’ 4 Family Guy 5 Family Guy 5 ‘Happy Gilmore’ (PG-13, ’96) ›› Adam Sandler. -

Food Network Canada Delves Into Cheese: a Love Story, Hosted by the World’S Youngest Maître Fromager, Afrim Pristine

LOVE AT FIRST BITE: FOOD NETWORK CANADA DELVES INTO CHEESE: A LOVE STORY, HOSTED BY THE WORLD’S YOUNGEST MAÎTRE FROMAGER, AFRIM PRISTINE Corus Studios Original Docu-Series Cheese: A Love Story Debuts June 9 at 8 p.m. ET Summer Premieres Continue with BBQ Brawl: Flay vs Symon vs Jackson, Project Bakeover, Chopped: Martha Rules, and More Stream the Series Live and On Demand with STACKTV or the Global TV App Cheese: A Love Story Host, Afrim Pristine. Photo Courtesy of Food Network Canada. Get a first look here For images visit the Corus Media Centre To share this release socially use: https://bit.ly/3hh1Cou For Immediate Release TORONTO, May 10, 2021 – The creamy richness of Camembert, the smooth texture of fresh mozzarella, the oozy stream of melted raclette: arriving this summer, Food Network Canada and Corus Studios dive into the evolving world of cheese with food travel docu-series Cheese: A Love Story. Hosted by the world's youngest Maître Fromager (Cheese Master), Afrim Pristine travels the globe exploring the most iconic cheese locations and hidden gems to get a deeper look at one of the world’s greatest, and most beloved foods. Cheese: A Love Story makes its debut on June 9 at 8 p.m. ET on Food Network Canada. Afrim Pristine is Canada's leading cheese expert, owner of the Cheese Boutique in Toronto, Ont., and has over 25 years of cheese experience. His passion and commitment to learning more about this magical food stems from his father and family business of 50 years. -

Nexstar Media Group Stations(1)

Nexstar Media Group Stations(1) Full Full Full Market Power Primary Market Power Primary Market Power Primary Rank Market Stations Affiliation Rank Market Stations Affiliation Rank Market Stations Affiliation 2 Los Angeles, CA KTLA The CW 57 Mobile, AL WKRG CBS 111 Springfield, MA WWLP NBC 3 Chicago, IL WGN Independent WFNA The CW 112 Lansing, MI WLAJ ABC 4 Philadelphia, PA WPHL MNTV 59 Albany, NY WTEN ABC WLNS CBS 5 Dallas, TX KDAF The CW WXXA FOX 113 Sioux Falls, SD KELO CBS 6 San Francisco, CA KRON MNTV 60 Wilkes Barre, PA WBRE NBC KDLO CBS 7 DC/Hagerstown, WDVM(2) Independent WYOU CBS KPLO CBS MD WDCW The CW 61 Knoxville, TN WATE ABC 114 Tyler-Longview, TX KETK NBC 8 Houston, TX KIAH The CW 62 Little Rock, AR KARK NBC KFXK FOX 12 Tampa, FL WFLA NBC KARZ MNTV 115 Youngstown, OH WYTV ABC WTTA MNTV KLRT FOX WKBN CBS 13 Seattle, WA KCPQ(3) FOX KASN The CW 120 Peoria, IL WMBD CBS KZJO MNTV 63 Dayton, OH WDTN NBC WYZZ FOX 17 Denver, CO KDVR FOX WBDT The CW 123 Lafayette, LA KLFY CBS KWGN The CW 66 Honolulu, HI KHON FOX 125 Bakersfield, CA KGET NBC KFCT FOX KHAW FOX 129 La Crosse, WI WLAX FOX 19 Cleveland, OH WJW FOX KAII FOX WEUX FOX 20 Sacramento, CA KTXL FOX KGMD MNTV 130 Columbus, GA WRBL CBS 22 Portland, OR KOIN CBS KGMV MNTV 132 Amarillo, TX KAMR NBC KRCW The CW KHII MNTV KCIT FOX 23 St. Louis, MO KPLR The CW 67 Green Bay, WI WFRV CBS 138 Rockford, IL WQRF FOX KTVI FOX 68 Des Moines, IA WHO NBC WTVO ABC 25 Indianapolis, IN WTTV CBS 69 Roanoke, VA WFXR FOX 140 Monroe, AR KARD FOX WTTK CBS WWCW The CW WXIN FOX KTVE NBC 72 Wichita, KS -

A Study of Celebrity Cookbooks, Culinary Personas, and Inequality

G Models POETIC-1168; No. of Pages 22 Poetics xxx (2014) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Poetics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/poetic Making change in the kitchen? A study of celebrity cookbooks, culinary personas, and inequality Jose´e Johnston *, Alexandra Rodney, Phillipa Chong University of Toronto, Department of Sociology, 725 Spadina Avenue, Toronto, Ontario M5S 2J4, Canada ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: In this paper, we investigate how cultural ideals of race, class and Available online xxx gender are revealed and reproduced through celebrity chefs’ public identities. Celebrity-chef status appears attainable by diverse voices Keywords: including self-trained cooks like Rachael Ray, prisoner turned high- Food end-chef Jeff Henderson, and Nascar-fan Guy Fieri. This paper Persona investigates how food celebrities’ self-presentations – their culinary Cookbooks personas – relate to social hierarchies. Drawing from literature on Celebrity chefs the sociology of culture, personas, food, and gender, we carry out an Gender inductive qualitative analysis of celebrity chef cookbooks written Inequality by stars with a significant multi-media presence. We identify seven distinct culinary personas: homebody, home stylist, pin-up, chef- artisan, maverick, gastrosexual, and self-made man. We find that culinary personas are highly gendered, but also classed and racialized. Relating these findings to the broader culinary field, we suggest that celebrity chef personas may serve to naturalize status inequities, and our findings contribute to theories of cultural, culinary and gender stratification. This paper supports the use of ‘‘persona’’ as an analytical tool that can aid understanding of cultural inequalities, as well as the limited opportunities for new entrants to gain authority in their respective fields. -

Fall Flavours Culinary Festival Title Sponsor

The Prince Edward Island Fall Flavours Culinary Festival Title Sponsor September 4 – October 4 Official Festival Guide A unique culinary adventure highlighting authentic Prince Edward Island tastes & traditions. Incredible food, delightful venues, entertaining hosts, one-of-a-kind experiences. Some of the most fabulous and intimate food experiences you can imagine, including Signature Events hosted by popular CELEBRITY CHEF personalities! Signature Event Sponsors Tickets on sale now www.fallflavours.ca 1-866-960-9912 FOOD NETWORK is a trademark of Television Food Network G.P.; used with permission Welcome There’s so much that’s so good about Prince Edward Island, and our Fall Flavours Festival is a perfect example. The Festival features the best of our local foods and – with the expert preparation by our guest and local chef experts – lets us showcase them to perfection. This year’s Fall Flavours Festival brings you more than 60 different food events and activities. It also brings you some of North America’s most recognized and acclaimed chefs to join us as we celebrate Prince Edward Island’s culinary treasures. The entire Island is set for the Festival. From Tignish in the west to Souris in the east, communities all over the Island are showcasing the best we have to offer. And that best is spectacular - we are surrounded by some of the best food on the planet, and it’s never presented any better than during our Fall Flavours Festival. Enjoy! Event Types Events & Accommodation Packages Be sure to visit us online at www.fallflavours.ca for more details and information on special Fall Flavours events & accommodation packages. -

Daryl Hall and William Shatner to Join Diy Network’S Celebrity Roster in 2014

DARYL HALL AND WILLIAM SHATNER TO JOIN DIY NETWORK’S CELEBRITY ROSTER IN 2014 NEW YORK (For Immediate Release—April 1, 2014) From celebrities tackling home remodels to regular folks renovating their homes, DIY Network will premiere seven new series that focus on the realities of home improvement. The network’s latest addition to its “celebrity home rehab” franchise, The Shatner Project, premieres in October and will follow the home renovation of actor William Shatner, instantly recognizable to television fans as the original Star Trek captain, James T. Kirk, commander of the starship U.S.S. Enterprise; Sergeant T.J. Hooker of T.J. Hooker and Attorney Denny Crane of Boston Legal. In July, the highly anticipated series, Daryl’s Restoration Over-Hall will premiere, starring singer/songwriter Daryl Hall from the musical duo Hall & Oates as he revives the historic charm of an 18th century Connecticut home. In addition, popular licensed contractor Jason Cameron will help homeowners smash their way to gorgeous new spaces by wrecking and remodeling their worst rooms in the new series, Sledgehammer. “DIY Network offers an authentic look at the realities of dealing with any home improvement project,” said Steven Lerner, senior vice president of programming development, HGTV and DIY Network. “When fans see Daryl Hall chasing his passion for historical rehab or William Shatner remodeling his outdated LA pad, they’re getting a glimpse of a real renovation – and they’re seeing that no matter who you are, the challenges that come with tackling a home remodel are universal.” Additional new DIY Network series will include First Time Flippers featuring overzealous property virgins who put their do-it-yourself real estate skills to the ultimate test and Stone Age which follows father and son duo, Steve and Nick Rhule, as they build amazing custom outdoor designs, including waterfalls, patios and fire pits, one rock at a time. -

A 040909 Breeze Thursday

Post Comments, share Views, read Blogs on CaPe-Coral-daily-Breeze.Com Day three Little League CAPE CORAL county tourney continues DAILY BREEZE — SPORTS WEATHER: Partly Cloudy • Tonight: Mostly Clear • Wednesday: Sunny — 2A cape-coral-daily-breeze.com Vol. 48, No. 92 Tuesday, April 21, 2009 50 cents Man to serve life for home invasion shooting death Andrew Marcus told Lee Circuit Judge Mark Steinbeck Attorneys plan to appeal conviction during Morales’ sentencing hearing Monday, citing the use By CONNOR HOLMES der, two counts of attempted cutors. Two others were shot, of firearms to kill Gomez and [email protected] second-degree murder with a and another man was beaten injure two others. One of five defendants in the firearm and aggravated battery with a tire iron. Steinbeck sentenced Anibal 2005 home invasion shooting with a deadly weapon by a Lee Fort Myers police testified Morales to serve three manda- Morales death of Jose Gomez was sen- County jury in early February. they later found the murder tory life sentences and 15 years tenced to life in prison Monday Morales fatally shot Gomez weapon in Morales’ car during in prison consecutively for the afternoon in a Lee County through the heart during a rob- a traffic stop. charges of which he has been courtroom. bery at 18060 Nalle Road, “We believe this case calls convicted. Anibal Morales, 22, was North Fort Myers, in November for the maximum sentence ... ” convicted of first-degree mur- 2005, according to state prose- Assistant State Attorney See SENTENCE, page 6A Expert speaker City manager calls take-home vehicle audit report wrong Refuses to go into detail By GRAY ROHRER [email protected] “The finding that the city Cape Coral City Manager is paying insurance on Terry Stewart denied one of the more cars than it owns is more glaring contentions of the inaccurate.” city’s take-home vehicle audit report Monday, saying the city — City Manager is not paying insurance on Terry Stewart more vehicles than it owns. -

KFDX * 3 Basic

Channel Package Channel Name Number Basic NBC - KFDX * 3 Basic NBC - KFOR 4 Basic ABC - KOCO 5 Basic CBS - KAUZ * 6 Basic ABC - KSWO * 7 Basic KSBI 8 Basic CBS - KWTV 9 Basic CW - KAUZ * 10 Basic CW - KOCB 11 Basic FOX - KOKH 12 Basic PBS - KETA 13 Basic FOX - KJTL * 14 Basic Freedom 43- KAUT 15 Basic EWTN 16 Basic ION - KOPX 17 Basic TBN - KTBO 18 Basic C-SPAN 96 Basic Court TV - KAUT 160 Basic Escape - KAUT 161 Basic AntTV - KFOR 170 Basic Justice - KFOR 171 Basic MeTV - KOCO 180 Basic New 9 Now - KWTV 190 Basic TBD - KOCB 200 Basic Comet - KOCB 201 Basic Charge! KOKH 210 Basic Stadium - KOKH 211 Basic LAFF - KSBI 220 Basic Grit - KSBI 221 Basic Telemundo - KTUZ 230 Basic OETA Create 235 Basic OETA Kids 236 Basic LAFF - KFDX * 240 Basic Telemundo - KSWO * 250 Basic MeTV - KSWO * 251 Basic My Network TV - KJBO * 260 Basic Grit - KJTL * 270 Basic Bounce - KJTL * 271 Basic QVC 280 Basic Shop HQ 281 Basic Jewelry TV 282 Basic Home Shopping Network 283 Essential Lifetime Television 29 Essential ESPN 30 Essential ESPN2 31 Essential Fox Sports Oklahoma 35 Essential Fox Sports Plus 36 Essential Fox Sports 1 37 Essential The Golf Channel 40 Essential TBS 41 Essential TNT 42 Essential NBC Sports Network 45 Essential Tennis Channel 47 Essential Disney Channel 54 Essential Animal Planet 57 Essential National Geographic 58 Essential Nickelodeon 60 Essential Cartoon Network 68 Essential Hallmark Channel 73 Essential Hallmark Movies & Mysteries 74 Essential Hallmark Drama 75 Essential Lifetime Movie Network 76 Essential HGTV 78 Essential Food Network -

I Love to Eat by James Still in Performance: April 15 - June 27, 2021

Commonweal Theatre Company presents I Love To Eat by James Still In performance: April 15 - June 27, 2021 products and markets. Beard nurtured a genera- tion of American chefs and cookbook authors who have changed the way we eat. James Andrew Beard was born on May 5, 1903, in Portland, Oregon, to Elizabeth and John Beard. His mother, an independent English woman passionate about food, ran a boarding house. His father worked at Portland’s Customs House. The family spent summers at the beach at Gearhart, Oregon, fishing, gathering shellfish and wild berries, and cooking meals with whatever was caught. He studied briefly at Reed College in Portland in 1923, but was expelled. Reed claimed it was due to poor scholastic performance, but Beard maintained it was due to his homosexuality. Beard then went on the road with a theatrical troupe. He lived abroad for several years study- ing voice and theater but returned to the United States for good in 1927. Although he kept trying to break into the theater and movies, by 1935 he needed to supplement what was a very non-lucra- Biography tive career and began a catering business. With From the website of the James Beard Founda- the opening of a small food shop called Hors tion: jamesbeard.org/about d’Oeuvre, Inc., in 1937, Beard finally realized that his future lay in the world of food and cooking. nointed the “Dean of American cookery” by In 1940, Beard penned what was then the first Athe New York Times in 1954, James Beard major cookbook devoted exclusively to cock- laid the groundwork for the food revolution that tail food, Hors d’Oeuvre & Canapés.