Women in Mexican Folk Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Postclassic Aztec Figurines and Domestic Ritual

Copyright by Maribel Rodriguez 2010 The Thesis Committee for Maribel Rodriguez Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Postclassic Aztec Figurines and Domestic Ritual APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Julia Guernsey David Stuart Postclassic Aztec Figurines and Domestic Ritual by Maribel Rodriguez, B.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin December 2010 Dedication Esto esta dedicado en especial para mi familia. Acknowledgements There are my academicians and friends I would like to extend my sincere gratitude. This research began thanks to Steve Bourget who encouraged and listened to my initial ideas and early stages of brainstorming. To Mariah Wade and Enrique Rodriguez-Alegria I am grateful for all their help, advice, and direction to numerous vital resources. Aztec scholars Michael Smith, Jeffrey and Mary Parsons, Susan T. Evans, and Salvador Guilliem Arroyo who provided assistance in the initial process of my research and offered scholarly resources and material. A special thank you to my second reader David Stuart for agreeing to be part of this project. This research project was made possible from a generous contribution from the Art and Art History Department Traveling grant that allowed me the opportunity to travel and complete archival research at the National American Indian History Museum. I would also like to thank Fausto Reyes Zataray for proofreading multiple copies of this draft; Phana Phang for going above and beyond to assist and support in any way possible; and Lizbeth Rodriguez Dimas and Rosalia Rodriguez Dimas for their encouragement and never ending support. -

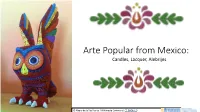

Intro Alebrije.Pdf

Arte Popular from Mexico: Candles, Lacquer, Alebrijes © Alvaro de la Paz Franco / Wikimedia Commons/ CC BY-SA 4.0 What is arte popular? Arte Popular is a Spanish term that translates to Popular Art in English. Another word for Arte Popular is artesanias. These can be arts like paintings and pottery, but they also include food, dance, and clothes. These arts are unique to Mexico and the communities that live in it. After the Mexican Revolution of the 1910s, focus was turned to Native Amerindian and farming communities. These communities were creating works of art but they had been ignored. But, after the revolution, Mexico needed something that could unite the people of Mexico. They decided to use the traditional arts of its people. Arte popular/artesanias became the heart of Mexico. You can go to Mexico now and visit artists’ workshops and © Thelmadatter / Edgar Adalberto Franco Martinez Ayotoxco De Guerrero, Puebla at see how they create their beautiful art. the Encuentro de las Colecciones de Arte Popular Valoración y Retos at the Franz Mayer Museum in Mexico City / Wikimedia Commons/ CC BY-SA 4.0 Arte popular/artesanias are traditions of many years within their communities. It is this community aspect that has provided Mexico with an art that focuses on the everyday people. It is why the word ‘popular’ is used to label these kinds of arts. The amazing objects they create, whether it is ceramic bowls or painted chests, are all unique and specific to the communities This is why there is so much variety in Mexico, because it is a large country. -

![Cuaderno 90 2021 Cuadernos Del Centro De Estudios En Diseño Y Comunicación [Ensayos]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8283/cuaderno-90-2021-cuadernos-del-centro-de-estudios-en-dise%C3%B1o-y-comunicaci%C3%B3n-ensayos-238283.webp)

Cuaderno 90 2021 Cuadernos Del Centro De Estudios En Diseño Y Comunicación [Ensayos]

ISSN 1668-0227 Año 21 Número 90 Enero Cuaderno 90 2021 Cuadernos del Centro de Estudios en Diseño y Comunicación [Ensayos] Investigar en Diseño: del complejo y multívoco diálogo entre el Diseño y las artesanías Marina Laura Matarrese y Luz del Carmen Vilchis Esquivel: Prólogo || Eje 1 Reflexiones conceptuales acerca del cruce entre diseño y artesanía | Luz del Carmen Vilchis Esquivel: Del símbo- lo a la trama | María Laura Garrido: La división arte/artesanía y su relación con la construcción de una historia del diseño | Marco Antonio Sandoval Valle: Relaciones de complejidad e identidad entre artesanía y diseño | Miguel Angel Rubio Toledo: El Diseño sistémico transdisciplinar para el desarrollo sostenible neguentró- pico de la producción artesanal | Yésica A. del Moral Zamudio: La innovación en la creación y comercialización de animales fan- tásticos en Arrazola, Oaxaca | Mónica Susana De La Barrera Me- dina: El diseño como objeto artesanal de consumo e identidad || Eje 2. La relación diseño y artesanía en los pueblos indígenas | Paola Trocha: Las artesanías Zenú: transformaciones y continui- dades como parte de diversas estrategias artesanales | Mercedes Martínez González y Fernando García García: El espejo en que nos vemos juntos: la antropología y el diseño en la creación de un video mapping arquitectónico con una comunidad purépecha de México | Paolo Arévalo Ortiz: La cultura visual en el proceso del tejido Puruhá | Daniela Larrea Solórzano: La artesanía salasaca y sus procesos de transculturación estética | Annabella Ponce Pérez y Carolina Cornejo Ramón: El diseño textil como resultado de la interacción étnica en Quito, a finales del siglo XVIII | Verónica Ariza y Mar Itzel Andrade: La relación artesanía y diseño. -

Movements of Diverse Inquiries As Critical Teaching Practices Among Charros, Tlacuaches and Mapaches Stephen T

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Open Access Dissertations 9-2012 Movements of Diverse Inquiries as Critical Teaching Practices Among Charros, Tlacuaches and Mapaches Stephen T. Sadlier University of Massachusetts Amherst, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Sadlier, Stephen T., "Movements of Diverse Inquiries as Critical Teaching Practices Among Charros, Tlacuaches and Mapaches" (2012). Open Access Dissertations. 664. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations/664 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MOVEMENTS OF DIVERSE INQUIRIES AS CRITICAL TEACHING PRACTICES AMONG CHARROS, TLACUACHES AND MAPACHES A Dissertation Presented by STEPHEN T. SADLIER Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION September 2012 School of Education Language, Literacy, and Culture © Copyright by Stephen T. Sadlier 2012 All Rights Reserved MOVEMENTS OF DIVERSE INQUIRIES AS CRITICAL TEACHING PRACTICES AMONG CHARROS,1 TLACUACHES2 AND MAPACHES3 A Dissertation Presented By STEPHEN T. SADLIER Approved as to style and content -

THE REBOZO Marta Turok [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2016 SOME NATIONAL GOODS IN 1871: THE REBOZO Marta Turok [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Art Practice Commons, Fashion Design Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Fine Arts Commons, and the Museum Studies Commons Turok, Marta, "SOME NATIONAL GOODS IN 1871: THE REBOZO" (2016). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 993. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/993 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Crosscurrents: Land, Labor, and the Port. Textile Society of America’s 15th Biennial Symposium. Savannah, GA, October 19-23, 2016. 511 SOME NATIONAL GOODS IN 1871: THE REBOZO1 Marta Turok [email protected], [email protected] The history of rebozos and jaspe (ikat) in Mexico still presents many enigmas and fertile field for research. Public and private collections in Mexican and foreign museums preserve a variety of rebozos from the mid-18th through the 20th centuries. However, it has been complicated to correlate these extant pieces with exact places of production and dates. Other sources such as written accounts and images focus mostly on their social uses, sometimes places of production or sale are merely mentioned yet techniques and designs are the information least dealt with. -

Born of Clay Ceramics from the National Museum of The

bornclay of ceramics from the National Museum of the American Indian NMAI EDITIONS NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION WASHINGTON AND NEW YORk In partnership with Native peoples and first edition cover: Maya tripod bowl depicting a their allies, the National Museum of 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 bird, a.d. 1–650. campeche, Mexico. the American Indian fosters a richer Modeled and painted (pre- and shared human experience through a library of congress cataloging-in- postfiring) ceramic, 3.75 by 13.75 in. more informed understanding of Publication data 24/7762. Photo by ernest amoroso. Native peoples. Born of clay : ceramics from the National Museum of the american late Mississippian globular bottle, head of Publications, NMai: indian / by ramiro Matos ... [et a.d. 1450–1600. rose Place, cross terence Winch al.].— 1st ed. county, arkansas. Modeled and editors: holly stewart p. cm. incised ceramic, 8.5 by 8.75 in. and amy Pickworth 17/4224. Photo by Walter larrimore. designers: ISBN:1-933565-01-2 steve Bell and Nancy Bratton eBook ISBN:978-1-933565-26-2 title Page: tile masks, ca. 2002. Made by Nora Naranjo-Morse (santa clara, Photography © 2005 National Museum “Published in conjunction with the b. 1953). santa clara Pueblo, New of the american indian, smithsonian exhibition Born of Clay: Ceramics from Mexico. Modeled and painted ceram institution. the National Museum of the American - text © 2005 NMai, smithsonian Indian, on view at the National ic, largest: 7.75 by 4 in. 26/5270. institution. all rights reserved under Museum of the american indian’s Photo by Walter larrimore. -

Aztec Figurine Studies. in the Post-Classic

Foreword: Aztec Figurine Studies Michael E. Smith Arizona State University Ceramic figurines are one of the mystery artifact categories of ancient Mesoamerica. Although figurines are abundant at archaeological sites from the Early Formative period through Early Colonial Spanish times, we know very little about them. How were figurines used? Who used them? What was their symbolic meaning? Did these human-like objects portray deities or people? Most scholars believe that ceramic figurines were used in some way in rites or ceremonies, but it has been difficult to find convincing evidence for their specific uses or meanings. The lack of knowledge about the use and significance of ceramic figurines is particularly striking for the Aztec culture of central Mexico. 1 Early Spanish chroniclers devoted literally thousands of pages to descriptions of Aztec religion, yet they rarely mentioned figurines. Ritual codices depict numerous gods, ceremonies, and mythological scenes, yet figurines are not included. Today we have a richly detailed understanding of many aspects of Aztec religion, but figurines play only a minor role in this body of knowledge. An important reason for the omission of figurines from the early colonial textual accounts is that these objects were almost certainly used primarily by women—in the home—for rites of curing, fertility, and divination (Cyphers Guillén 1993; Heyden 1996; Smith 2002), and the Spanish friars who wrote the major accounts of Aztec culture had little knowledge of Aztec women or domestic life (Burkhart 1997; Rodríguez-Shadow 1997). Ceramic figurines can provide crucial information on Aztec domestic ritual and life. They offer a window on these worlds that are very poorly described in written sources. -

Observatori De Política Exterior Europea

INSTITUT UNIVERSITARI D’ESTUDIS EUROPEUS Obs Observatori de Política Exterior Europea Working Paper n. 47 Mayo de 2003 The European Union Perception of Cuba: From Frustation to Irritation Joaquín Roy Catedrático ‘Jean Monnet’ y director del Centro de la Unión Europea de la Universidad de Miami Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Edifici E-1 08193 Bellaterra Barcelona (España) © Institut Universitari d'Estudis Europeus. Todos derechos reservados al IUEE. All rights reserved. Working Paper 47 Observatori de Política Exterior Europea On Friday May 16, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Cuba summoned the newly-appointed charge- d’affairs of the European Commission in Havana and announced the withdrawal of the application procedure for membership in the Cotonou Agreement of the Africa, Caribbean, and Pacific (ACP) countries, and in fact renouncing to benefit from European development aid.1 In a blistering note published in the Granma official newspaper of the Cuban Communist Party, the government blamed the EU Commission for exerting undue pressure, its alleged alignment with the policies of the United States, and censure for the measures taken by Cuba during the previous weeks.2 In reality, Cuba avoided an embarrasin flat rejection for its application. This was the anti-climatic ending for a long process that can be traced back to the end of the Cold War, in a context where Cuba has been testing alternative grounds to substitute for the overwhelming protection of the Soviet Union. I. An overall assessment3 In April 2003 an extremely serious crisis affected Cuba’s international relations, and most especially its link with Europe. It was the result of the harshness of the reprisals against the dissidents and the death sentences imposed on three hijackers of a ferry. -

Número 87 Completo

Número 87 Octubre, Noviembre y Diciembre 2020 Editado por Luis Gómez Encinas Multidisciplinary, quarterly, open access and peer-reviewed journal Licencia CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 apostadigital.com Número 87 Octubre, Noviembre y Diciembre 2020 Editado por Luis Gómez Encinas La portada ha sido diseñada usando imágenes de pixabay.com Aposta, publicada trimestralmente, es una revista digital internacional de ciencias sociales con perspectiva interdisciplinaria, que tiene como misión promover el debate y la reflexión sobre los temas esenciales de la sociedad contemporánea a través de la publicación de artículos científicos de carácter empírico y teórico. Aposta fue creada en 2003, con el planteamiento de ofrecer una revista en acceso abierto a autores de España y América Latina en donde divulgar su producción científica de calidad sobre el análisis sociológico e incluir campos afines, como la antropología, la filosofía, la economía, la ciencia política, para ampliar y enriquecer la investigación social. Normas para autores Si quieres saber cómo publicar en nuestra revista, recomendamos revisar las directrices para autores/as en: http://apostadigital.com/page.php?page=normas-autores Políticas Puedes consultar las políticas de nuestra revista en: http://apostadigital.com/page.php?page=politicas Director / Editor Luis Gómez Encinas Contacto C/ Juan XXIII, 21 28938 Móstoles Madrid, España luisencinas[at]apostadigital[.]com Servicios de indexación: BASE, Capes, CARHUS, CIRC, Copac, Dialnet, DICE, DOAJ, EBSCO, ERIH PLUS, ESCI (Web of Science), Google Scholar, -

Las Técnicas Textiles Y La Historia Cultural De Los Pueblos Otopames

Las técnicas textiles y la historia cultural de los pueblos otopames Alejandro de Ávila Blomberg Jardín Etnobotánico y Museo Textil de Oaxaca Las comunidades otopames conservaron hasta mediados del siglo XX uno de los repertorios textiles más diversificados en nuestro continente. Buena parte de las materias primas y las técnicas de tejido han sido abandonadas en las últimas décadas, lo que nos obliga a recurrir a las notas de campo y las colecciones reunidas por Bodil Christensen y otros etnógrafos pioneros para estudiarlas. En este trabajo examino las plantas y animales que proveían las fibras y colorantes textiles que fueron documentados en las investigaciones tempranas. Muestro que las afinidades biogeográficas de esas especies no corresponden con lo que esperaríamos encontrar en una muestra aleatoria de la flora y la fauna de las zonas por encima de los 1500 metros de altitud, donde se asienta la mayor parte de la población otopame desde la antigüedad. Ello indica que hay una preferencia marcada por utilizar materias primas provenientes de la biota tropical, y sugiere que la historia temprana de innovación tecnológica en las zonas bajas delimitó el inventario de fibras y tintes textiles en toda Mesoamérica, incluso en su periferia septentrional sobre el altiplano. Las fuentes de información referidas me permiten catalogar también las distintas técnicas de tejido y teñido vigentes entre los pueblos otopames de 1880 a 1960, para mostrar una variación mayor que entre los grupos vecinos. Relaciono la persistencia de este patrón cultural con la ubicación de varias comunidades otomíes y pames en la frontera norte de conformaciones políticas y económicas más complejas en la época prehispánica, área convertida posteriormente en una franja marginal del estado novohispano y decimonónico. -

The European Union Perception of Cuba: from Frustration to Irritation* Joaquín Roy

RFC-03-2 The European Union Perception of Cuba: From Frustration to Irritation* Joaquín Roy EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Fidel Castro dramatically selected the commemoration of the 50th anniversary of his failed attack against the Moncada Barracks in Santiago de Cuba on July 26, 1953, for his rejection of any kind of humanitarian assistance, economic cooperation, and political dialogue with the European Union (EU) and its member states, signalling one of the lowest points in European- Cuban relations.1 Just days before the anniversary of what later history would recognize as the prelude of the Cuban Revolution, the European Union’s Foreign Relations Council issued a harsh criticism of the regime’s latest policies and personal insults against some European leaders (notably, Spain’s José María Aznar), in essence freezing all prospects of closer relations. The overall context was, of course, the global uncertainty of the U.S. occupation of Iraq in the aftermath of the post-September 11 tension. Having survived the end of the Cold War and the perennial U.S. harassment, the Castro regime seemed to have lost its most precious alternative source of international cooperation, if not economic support. RESUMEN Fidel Castro escogió de manera espectacular la fecha de conmemoración del Aniversario 50 del fallido ataque al cuartel Moncada en Santigo de Cuba, el 26 de julio de 1953, para anunciar su rechazo a cualquier tipo de ayuda humanitaria, cooperación económica y diálogo político con la Unión Europea (UE) y sus estados miembros, lo cual marca uno de los niveles más bajos de las relaciones entre Cuba y la UE. -

Publicaciones Periódicas-Pág.513-578-IA-7

Publicaciones periódicas En la primera subsección, dedicada a "Revistas científicas y de divul gación", se presentan las tablas de contenido de 57 números de 30 re vistas y anuarios. En la segunda subsección se ofrece esta misma clase de información sobre boletinesinternos y algunas publicaciones que mayormente son de este mismo tipo de circulación y/ o están vinculadas de manera particu larmente estrecha con las actividades de la institución editora respectiva. Esta información, aunque incompleta, permite tener una impresión de la gran cantidad de temas estudiados y de actividades llevadas a cabo en muchas instituciones mexicanas centradas en alguna rama de las cien cias antropológicas. Cabe señalar que a veces, el que un boletín presente en un volumen del anuario INVeNTaRio aNTROPOLÓGICO, no vuelva a aparecer en el si guiente, significa que dejó de publicarse por un tiempo o para siempre, pero otras veces esto se debe solamente a que se perdió el contacto entre el anuario y los editores de la publicación en cuestión. Por ello, y con el objetivo de mantener cierta continuidad, se incluye en esta sección oca sionalmente información sobre material publicado no solamente durante el año de referencia, sino durante uno o dos anteriores. La tercera subsección informa nuevamente sobre revistas estudian tiles, en este caso de publicaciones editadas en las ciudades de México y Mérida. 513 Revistas científicas y de divulgación ALQUIMIA [Sistema Nacional de Fototecas-INAH; ISSN 1405-7786] Año 3, número 8, enero-abril de 2000 ["Fotógrafasen México: 1880-1955"] • José Antonio Rodríguez, Nu~vas razones para una añeja historia • Rebeca Monroy Nasr, Mujeres en el proceso fotográfico (1880-1950) • Antonio Saborit, Algunas fotógrafas extranjeras y sus sorprendentes imágenes mexicanas • Alicia Sánchez Mejorada, La fuerza evocadora de La Castañeda PORTAFOLIO • Cárlos A.