St Sauveur- Le-Vicomte

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carte De Visite APPEVILLE - 50500

MARAIS DU COTENTIN ET DU BESSIN PARC NATUREL RÉGIONAL AIGNERVILLE - 14710 ........................ F4 BOUTTEVILLE - 50480 ...................... D3 CROSVILLE-SUR-DOUVE - 50360 ....... B3 HAM (Le) - 50310 .............................. C2 MEAUFFE (La) - 50880 ..................... D5 ORGLANDES - 50390 ....................... B2 ST-GEORGES-DE-BOHON - 50500 ..... C4 STE-MARIE-DU-MONT - 50480 .......... D3 AIREL - 50680 .................................. E4 BREVANDS - 50500 ........................... D3 DEZERT (Le) - 50620 ......................... D5 HAYE-DU-PUITS (La) - 50250 ............. B4 MEAUTIS - 50500 ............................ C4 OSMANVILLE - 14230 ....................... E3 ST-GERMAIN-DE-VARREVILLE - 50480 ....D2 STE-MERE-EGLISE - 50480 .............. C2 Tourist map AMFREVILLE - 50480 ....................... C2 BRICQUEVILLE - 14710 .......................E4 DOVILLE - 50250 ............................... B3 HEMEVEZ - 50700 ............................ B2 MESNIL-EURY (Le) - 50570 ............... D5 PERIERS - 50190 .............................. B5 ST-GERMAIN-DU-PERT - 14230 ......... E3 SAINTENY - 50500 .......................... C4 AMIGNY - 50620 .............................. D5 BRUCHEVILLE - 50480 ..................... D3 ECAUSSEVILLE - 50310 .................... C2 HIESVILLE - 50480 ........................... D3 MESNIL-VENERON (Le) - 50620 ......... D4 PICAUVILLE - 50360 ......................... C3 ST-GERMAIN-SUR-AY - 50430 ........... A4 SAON - 14330 .................................. F4 ANGOVILLE-AU-PLAIN - 50480 ......... -

The United States Airborne Divisions, and Their Role on June 6, 1944

The Histories Volume 6 | Issue 1 Article 3 The nitU ed States Airborne Divisions, and Their Role on June 6, 1944 Dennis Carey Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/the_histories Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carey, Dennis () "The nitU ed States Airborne Divisions, and Their Role on June 6, 1944," The Histories: Vol. 6 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/the_histories/vol6/iss1/3 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Scholarship at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The iH stories by an authorized editor of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Histories, Volume 6, Number 1 2 I The United States Airborne Divisions, and Their Role on June 6,1944 By Dennis Carey ‘07 The United States Airborne Divisions that were dropped behind Utah Beach in the early morning hours of June 6,1944 played a critical role in the eventual success of Operation Overlord. On the evening of June 5th, General Eisenhower visited the men of the 101st Airborne division as they geared up in preparation for their jump. In making his rounds among the troops giving his words of encouragement, a paratrooper remarked “Hell, we ain’t worried General. It’s the Krauts that ought to be worrying now.”1 This is just one example of the confidence and fortitude that the men of both the 82nd and 101st Airborne divisions possessed on the eve of Operation Overlord. -

Omaha Beach- Normandy, France Historic Trail

OMAHA BEACH- NORMANDY, FRANCE HISTORIC TRAIL OMAHA BEACH-NORMANDY, FRANCE HISTORIC TRANSATLANTICTRAIL COUNCIL How to Use This Guide This Field Guide contains information on the Omaha Beach- Normandy Historical Trail designed by members of the Transatlantic Council. The guide is intended to be a starting point in your endeavor to learn about the history of the sites on the trail. Remember, this may be the only time your Scouts visit the Omaha Beach area in their life so make it a great time! While TAC tries to update these Field Guides when possible, it may be several years before the next revision. If you have comments or suggestions, please send them to [email protected] or post them on the TAC Nation Facebook Group Page at https://www.facebook.com/groups/27951084309/. This guide can be printed as a 5½ x 4¼ inch pamphlet or read on a tablet or smart phone. Front Cover: Troops of the 1st Infantry Division land on Omaha Beach Front Cover Inset: Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial OMAHA BEACH-NORMANDY, FRANCE 2 HISTORIC TRAIL Table of Contents Getting Prepared……………………… 4 What is the Historic Trail…………5 Historic Trail Route……………. 6-18 Trail Map & Pictures..…….…..19-25 Background Material………..26-28 Quick Quiz…………………………..…… 29 B.S.A. Requirements…………..……30 Notes……………………………………..... 31 OMAHA BEACH-NORMANDY, FRANCE HISTORIC TRAIL 3 Getting Prepared Just like with any hike (or any activity in Scouting), the Historic Trail program starts with Being Prepared. 1. Review this Field Guide in detail. 2. Check local conditions and weather. 3. Study and Practice with the map and compass. -

Operation Overlord James Clinton Emmert Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2002 Operation overlord James Clinton Emmert Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Emmert, James Clinton, "Operation overlord" (2002). LSU Master's Theses. 619. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/619 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OPERATION OVERLORD A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Arts in The Interdepartmental Program in Liberal Arts by James Clinton Emmert B.A., Louisiana State University, 1996 May 2002 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis could not have been completed without the support of numerous persons. First, I would never have been able to finish if I had not had the help and support of my wife, Esther, who not only encouraged me and proofed my work, but also took care of our newborn twins alone while I wrote. In addition, I would like to thank Dr. Stanley Hilton, who spent time helping me refine my thoughts about the invasion and whose editing skills helped give life to this paper. Finally, I would like to thank the faculty of Louisiana State University for their guidance and the knowledge that they shared with me. -

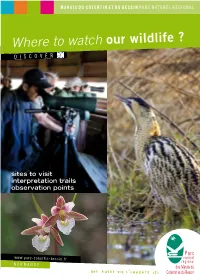

Where to Watch Our Wildlife ? D I S C O V E R

MARAIS DU COTENTIN ET DU BESSIN PARC NATUREL RÉGIONAL Where to watch our wildlife ? D I S C O V E R sites to visit interpretation trails observation points www.parc-cotentin-bessin.fr N O R M A N D Y PARC NATUREL RÉGIONAL DES MARAIS DU COTENTIN ET DU BESSIN Environment and landscapes Marshlands CHERBOURG-OCTEVILLE Introduction Foreshore BARFLEUR 1 The Mont de Doville p. 3 FieldsF and hedgerows QUETTEHOU 2 The Havre at Saint-Germain-sur-Ay p. 4 CHERBOURG-OCTEVILLE 3 Mathon peat bog p. 6 CHERBOURG-OCTEVILLE Moor 4 The Lande du Camp p. 7 D 14 Wood or forest 5 Saint-Patrice-de-Claids heaths p. 8 La Sinope VALOGNES 6 Sursat pond p. 9 SNCF Dune oro beach N 13 D 42 7 Rouges-Pièces reedbed p. 10 D 24 MONTEBOURG 8 p. 11 BRICQUEBEC Bohons Reserve Le Merderet 16 D 42 Marshlands, 9 D 14 D 421 The Port des Planques p. 12 between two coastlines… N 13 La Douve 18 D 15 10 D 900 The Château de la Rivière p. 13 11 The Claies de Vire p. 14 D 2 STE-MÈRE- 12 19 ÉGLISE The Aure marshes p. 15 ST-SAUVEUR- LE-VICOMTE D 15 Chef-du-Pont D 913 17 13 The Colombières countryside p. 16 D 70 Baie D 514 BARNEVILLE- des Veys D 15 La Douve D 70 CARTERET Les Moitiers- 14 The Ponts d’Ouve “Espace Naturel Sensible” p. 17 Le Gorget en-Bauptois D 113 20 La Senelle 15 15 The Veys bay p. -

COMMUNAUTE DE COMMUNES DE LA BAIE DU COTENTIN À Carentan Les Marais (50)

CONSEIL INDEPENDANT EN ENVIRONNEMENT COMMUNAUTE DE COMMUNES DE LA BAIE DU COTENTIN à Carentan les Marais (50) Projet de construction d’un abattoir de proximité et d’un atelier de découpe à Méautis Demande d’autorisation environnementale PARTIE 2 : ETUDE D’IMPACT GES n° 16658 Juin 2018 AGENCE OUEST AGENCE NORD AGENCE EST AGENCE SUD-EST-CENTRE AGENCE SUD-OUEST Z.I des Basses Forges 80 rue Pierre-Gilles de Gennes 870 avenue Denis Papin 139 Imp de la Chapelle - 42155 Forge 35530 NOYAL-SUR-VILAINE 02000 BARENTON BUGNY 54715 LUDRES ST-JEAN ST-MAURICE/LOIRE 79410 ECHIRÉ Tél. 02 99 04 10 20 Tél. 03 23 23 32 68 Tél. 03 83 26 02 63 Tél. 04 77 63 30 30 Tél. 05 49 79 20 20 Fax 02 99 04 10 25 Fax 09 72 19 35 51 Fax 03 26 29 75 76 Fax 04 77 63 39 80 Fax 09 72 11 13 90 e-mail : [email protected] e-mail : [email protected] e-mail : [email protected] e-mail : [email protected] e-mail : [email protected] www.ges-sa.fr - GES S.A.S au capital de 150 000 € - Siège social : L’Afféagement 35340 LIFFRE - RCS Rennes B 330 439 415 - NAF 7219Z Communauté de Communes de la Baie du Cotentin Partie 2 : Etude d’impact à Carentan les Marais (50) SOMMAIRE AVANT PROPOS _________________________________________________________________________ 5 TEXTES REGLEMENTAIRES ET PROCEDURE ___________________________________________ 6 DESCRIPTION DU PROJET 1. IDENTITE DU DEMANDEUR ____________________________________________________ 14 2. PRESENTATION DE L'ETABLISSEMENT ET DE LA DEMANDE ____________________ 14 2.1. -

MAGNEVILLE Version (1) Annule Et Remplace La Version Précédente 1/10

A la découverte de MAGNEVILLE Version (1) annule et remplace la version précédente 1/10 MAGNEVILLE Sommaire Identité, Toponymie page 1 Ferme-manoir de Saint-Louet page 7… Un peu d’histoire : Autres fermes-manoirs page 7… A savoir page 1… Monument 506th… page 8… Les personnes ou familles liées à la commune et leur histoire page 3… Cours d’eau page 8… Le patrimoine (public et privé), lieux et monuments à découvrir, événement : Lavoirs, Fontaines, Etangs page 8… Eglise page 4… Croix de chemin page 9… Château de La Cour page 5… Communes limitrophes & plans page 10… Ferme-Manoir de Beauval page 6… Randonner à Couville page 10… Sources page 10… Magneville appartient à l’arrondissement de Cherbourg, au canton de Bricquebec et appartenait à la communauté de communes du Cœur du Cotentin jusqu’à fin 2016. Désormais, la commune de Magneville appartient à la Communauté d’Agglomération du Cotentin (CAC). Les habitants de Magneville se nomment les Magnevil- lais(es). Magneville compte 339 habitants (recensement 2016) sur une superficie de 9.49 km², soit 36 hab. / km² (84,2 pour la Manche, 111 pour la Normandie et 116 pour la France). La Mairie Le nom de la paroisse est attesté sous les formes Magnevilla (1051-1066), Esware de Magnevilla (1164), Ma- gnevilla l’Esvarée (XIIe), Eswaredus de Magnevilla ( ?), Esgaret de Magnevilla ( ?), Magnavilla l’Esgarée (1240), Galterius Esguarez (v.1248). François de Beaurepaire (Historien et chercheur passionné par la toponymie qui a écrit un ouvrage de réfé- rence « les noms des communes et anciennes de la Manche »), confirme l’origine littérale de « grand do- maine » et indique que le déterminant l’Esgarée, aujourd’hui disparu, évoque un nom attesté localement au Moyen Âge comme le montre la mention de 1248. -

Clos Du Cotentin Valognes

THE ESSENTIELS CLOS DU COTENTIN VALOGNES #DISCOVERIES www.encotentin.fr 1 LET’S TELL A STORY THE CLOS DU COTENTIN… A JOURNEY BACK IN TIME HOW DO YOU FEEL This is the right place, the Clos du Cotentin ABOUT THAT? includes three towns rich with 2000 years of history: Valognes, nicknamed “Le Petit Versailles Normand” (small Normandy Versailles). Saint- Sauveur-le-Vicomte “Bourgade jolie comme un village d’Ecosse” (as pretty as a Scottish village) and Bricquebec-en-Cotentin “La cité du Donjon” (the city of the tower). The cultural diversity is enchanting: castles, private residences, museums, classified churches… For children, ask for the booklets “Coucou les p’tits cailloux” (Hi, little stones). These small booklets can be filled in by all the family and contain games and ways of discovering the heritage. You can collect all three: the first, about the medieval part of Valognes, the second on Bricquebec- en-Cotentin’s Castle and the third on Saint-Sauveur-le-Vicomte’s Castle (only in french). Deepen your knowledge of the Clos du Cotentin with guided visits and conferences by the “Pays d’Art et d’Histoire”, which take place throughout the year, as well as treasure hunts, criminal investigations and workshops for children (programs available). A team of guide lecturers with “a la carte” visits are also available for groups. Did you know? During the summer, every Tuesday afternoon, guided visits in french, in a horse-drawn carriage are organized, when you can discover the heritage of Valognes to the clip clop sound of horses’ hooves! Ideal for a family activity. -

Etat Des Lieux Etat Des Lieux Et Elements De Elements De

ETAT DES LIEUX ETETET ELEMENTS DE DIAGNOSTIC DUDUDU S.A.G.E. DOUVE TAUTE DOCUMENT VALIDE PAR LA COMMISSION LOCALE DE L’EAU DU 2424----01010101----2012201220122012 Mise à jour régulière des données Etat des lieux et éléments de diagnostic du SAGE Douve Taute – PNRMCB 2010 2 SOMMAIRE SSSOMMAIREOMMAIREOMMAIRE................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................3333 TTTABLE DES ILLUSTRATIOILLUSTRATIONSNSNSNS ...............................................................................................................................................................................................................................8888 PRESENTATION GENERALE DU TERRITOIRE..................................................10 TTTERRITOIRE ET POPULATPOPULATIONIONIONION ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................11111111 1. L'organisation du territoire : ...............................................................................................11 2. La population :.....................................................................................................................11 LLLES CARACTERISTIQUES PHYSIQUES DU BASSIN VERSANTVERSANTVERSANT...................................................................................................................12121212 -

Ça Bouge En Baie Du Cotentin !

Ça bouge en Baie du Cotentin ! Les nouvelles prestations et animations proposées Les nouveautés du territoire Faire jouer les 5 sens Le Clos des Pieds Nus aux 5 sens Tarifs : 10, route du Bauptois - Le Clos Verdier LES MOITIERS-EN-BAUPTOIS Adulte : 5 € 02 50 16 22 94 - 06 05 28 53 62 Enfant (3-16 ans) : 3 € Famille (2 ad. + 2 enfants.) : 13 € Parcours aménagé de 1,5 km à faire pieds nus. Afin d’ouvrir vos sens, vos pieds vont découvrir et ressentir plus d’une trentaine de matières différentes. Pour les amateurs de nature, des panneaux explicatifs vous permettront de découvrir le bienfait de certaines plantes. Un grand moment de partage pour les petits et les grands. Du 15 avril au 1er juillet : mercredi, week-end, jours fériés: 13h - 17h30. Du 2 juillet au 31 août : du mar. au dim. : 11h - 18h. En septembre. : Mercredi, week-end : 13h - 17h. En dehors de ces dates (de mi-avril à fin sept.) : groupes sur réservation (15 pers. min.) Escape Game Tarifs selon le nombre de joueurs : Le Blockhaus 3 joueurs : 27 €/pers 27 rue de la 101e Airborne - CARENTAN 4 joueurs : 25 €/pers 02 33 20 81 15 5 joueurs : 23 €/pers [email protected] 6 joueurs : 21 €/pers DURÉE DE L’EXPÉRIENCE : 1h30 Profitez d’une expérience 100% immersive en vous plongeant dans l’Histoire. Intrigues pensées selon les Soldats dans un Bunker ou Famille épisodes historiques du débarquement de 1944, décors de Résistants, faites votre choix et mobilier d’époque, mécanismes ingénieux : appréhendez l’Histoire sous un prisme didactique. -

La Baie De Seine: Hydrologie, Nutriments Et Ch Lorophylle (1978-1994) 14

La baie de Seine: hydrologie, nutriments et ch lorophylle (1978-1994) 14 - Alain Aminof; jean-François Guillaud, Roger Kérouel La baie de Seine: hydrologie, nutriments et chlorophylle (1978-1994) Alain Aminot, jean·François Guil/aud et Roger Kérouel ~ ....................................... " .... · · ' .... • ... · .... 0 .... ' , . ..... .... ~,. ~ ... _ . .... · ....... ,'-'fJ"!" ..... \. J , .... 2 La baie de Seine: hydrologie, nutriments et chlorophylle (1978-7994) < Sommaire Préambule 5 Résumé 7 Chapitre 1 : Le site et les apports Introduction 11 Apports en éléments nutritifs 12 Chapitre Il : Atlas des résultats Campagnes 17 Méthodes 19 Paramètres mesurés et prélèvements 19 Méthodes d'analyse 19 Présentation cartographique 19 Chapitre III : Caractéristiques spatio-temporelles Température 105 Salinité 105 Structu re spatiale 105 Cycles de marée 109 Diagrammes température-salinité (T-S) 111 Matériel particulaire 112 Relations turbidité-matières en suspension 112 Structure spatiale 113 Cycles de marée 117 Nutriments 118 Nitrate 118 Ammonium 119 Phosphate 120 Silicate 120 Nitrite 121 Urée 121 Pigments chlorophylliens 121 Oxygène dissous 122 Chapitre IV: Comportement des nutriments Schémas de dilution 127 Nitrate 127 Ammonium 127 Phosphate 127 Silicate 132 Consommation en nutriments 132 Consommation des nutriments au printemps 132 Consommation des nutriments en automne 129 Régénération des nutriments 141 Conclusion 145 Bibliographie 147 3 'K La baie de Seine: hydrologie, nutriments et chlorophylle (/978-1994) 4 La baie de Seine: hydrologie, nutriments et chlorophylle 17978-1994).$ Préambule L'enrichissement du milieu côtier en éléments Ce document représente la synthèse des données nutritifs (N, P, Si) devient préoccupant du fait des de nutriments acquises en baie de Seine depuis conséquences néfastes qui peuvent en découler, 1978, date des premières campagnes du CNEXO* généralisées sous le terme d'eutrophisation. -

Vii Corps, U.S

APPENDIX #1 CAPTURE OF CHERBOURG AND CONTENTIN PENINSULA BY VII CORPS, U.S. ARMY (6 June to 1 July 1944) The Initial Landings and Establishment of a Beachhead by 4th Infantry Division, 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions. (6-7 June) In the assault on the European Continent, which opened on the 6th of June, the US VII Corps, under the command of Major Gen. J. Lawton Collins, was assigned a position on the extreme Allied right. It had the mission of securing a beachhead on the Cotentin Peninsula, making contact with the US V Corps on its left, and seizing the major port of Cherbourg for use as a base for future operations. Chief among the considerations which influenced the detailed plans of the Corps were the beach defense proper; the inundated area immediately behind the beach; the River Douve, and the Prairies Marecaugeuses, which would serve as a defensive barrier on the South during the operations against Cherbourg; and the roads and bridges in the vicinity of Carentan which it was essential to control in order to insure a junction with the V Corps. Considerations of security prevented any air preparation, beyond the limited amount, which could be ascribed to routine coastal bombing, until the night of 5-6 June. That night heavy attacks were launched against key coastal batteries and other defenses in the area, and during a planned pause in the early morning bombing missions large flights of transport planes brought in major elements of two US Airborne Divisions. The 101st Airborne Division, commanded by Brig. Gen.