Highly Accurate Local Pseudopotentials of Li, Na, and Mg for Orbital Free Density Functional Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Empirical Pseudopotential Method

The empirical pseudopotential method Richard Tran PID: A1070602 1 Background In 1934, Fermi [1] proposed a method to describe high lying atomic states by replacing the complex effects of the core electrons with an effective potential described by the pseudo-wavefunctions of the valence electrons. Shortly after, this pseudopotential (PSP), was realized by Hellmann [2] who implemented it to describe the energy levels of alkali atoms. Despite his initial success, further exploration of the PSP and its application in efficiently solving the Hamiltonian of periodic systems did not reach its zenith until the middle of the twenti- eth century when Herring [3] proposed the orthogonalized plane wave (OPW) method to calculate the wave functions of metals and semiconductors. Using the OPW, Phillips and Kleinman [4] showed that the orthogonality of the va- lence electrons’ wave functions relative to that of the core electrons leads to a cancellation of the attractive and repulsive potentials of the core electrons (with the repulsive potentials being approximated either analytically or empirically), allowing for a rapid convergence of the OPW calculations. Subsequently in the 60s, Marvin Cohen expanded and improved upon the pseudopotential method by using the crystalline energy levels of several semicon- ductor materials [6, 7, 8] to empirically obtain the potentials needed to compute the atomic wave functions, developing what is now known as the empirical pseu- dopotential method (EPM). Although more advanced PSPs such as the ab-initio pseudopotentials exist, the EPM still provides an incredibly accurate method for calculating optical properties and band structures, especially for metals and semiconductors, with a less computationally taxing method. -

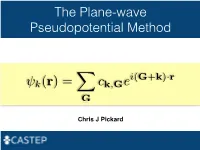

The Plane-Wave Pseudopotential Method

The Plane-wave Pseudopotential Method i(G+k) r k(r)= ck,Ge · XG Chris J Pickard Electrons in a Solid Nearly Free Electrons Nearly Free Electrons Nearly Free Electrons Electronic Structures Methods Empirical Pseudopotentials Ab Initio Pseudopotentials Ab Initio Pseudopotentials Ab Initio Pseudopotentials Ab Initio Pseudopotentials Ultrasoft Pseudopotentials (Vanderbilt, 1990) Projector Augmented Waves Deriving the Pseudo Hamiltonian PAW vs PAW C. G. van de Walle and P. E. Bloechl 1993 (I) PAW to calculate all electron properties from PSP calculations" P. E. Bloechl 1994 (II)! The PAW electronic structure method" " The two are linked, but should not be confused References David Vanderbilt, Soft self-consistent pseudopotentials in a generalised eigenvalue formalism, PRB 1990 41 7892" Kari Laasonen et al, Car-Parinello molecular dynamics with Vanderbilt ultrasoft pseudopotentials, PRB 1993 47 10142" P.E. Bloechl, Projector augmented-wave method, PRB 1994 50 17953" G. Kresse and D. Joubert, From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method, PRB 1999 59 1758 On-the-fly Pseudopotentials - All quantities for PAW (I) reconstruction available" - Allows automatic consistency of the potentials with functionals" - Even fewer input files required" - The code in CASTEP is a cut down (fast) pseudopotential code" - There are internal databases" - Other generation codes (Vanderbilt’s original, OPIUM, LD1) exist It all works! Kohn-Sham Equations Being (Self) Consistent Eigenproblem in a Basis Just a Few Atoms In a Crystal Plane-waves -

Introduction to DFT and the Plane-Wave Pseudopotential Method

Introduction to DFT and the plane-wave pseudopotential method Keith Refson STFC Rutherford Appleton Laboratory Chilton, Didcot, OXON OX11 0QX 23 Apr 2014 Parallel Materials Modelling Packages @ EPCC 1 / 55 Introduction Synopsis Motivation Some ab initio codes Quantum-mechanical approaches Density Functional Theory Electronic Structure of Condensed Phases Total-energy calculations Introduction Basis sets Plane-waves and Pseudopotentials How to solve the equations Parallel Materials Modelling Packages @ EPCC 2 / 55 Synopsis Introduction A guided tour inside the “black box” of ab-initio simulation. Synopsis • Motivation • The rise of quantum-mechanical simulations. Some ab initio codes Wavefunction-based theory • Density-functional theory (DFT) Quantum-mechanical • approaches Quantum theory in periodic boundaries • Plane-wave and other basis sets Density Functional • Theory SCF solvers • Molecular Dynamics Electronic Structure of Condensed Phases Recommended Reading and Further Study Total-energy calculations • Basis sets Jorge Kohanoff Electronic Structure Calculations for Solids and Molecules, Plane-waves and Theory and Computational Methods, Cambridge, ISBN-13: 9780521815918 Pseudopotentials • Dominik Marx, J¨urg Hutter Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics: Basic Theory and How to solve the Advanced Methods Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 0521898633 equations • Richard M. Martin Electronic Structure: Basic Theory and Practical Methods: Basic Theory and Practical Density Functional Approaches Vol 1 Cambridge University Press, ISBN: 0521782856 -

The Plane-Wave Pseudopotential Method

The Plane-Wave Pseudopotential Method Eckhard Pehlke, Institut für Laser- und Plasmaphysik, Universität Essen, 45117 Essen, Germany. Starting Point: Electronic structure problem from physics, chemistry, materials science, geology, biology, ... which can be solved by total-energy calculations. Topics of this (i) how to get rid of the "core electrons": talk: the pseudopotential concept (ii) the plane-wave basis-set and its advantages (iii) supercells, Bloch theorem and Brillouin zone integrals choices we have... Treatment of electron-electron interaction and decisions to make... Hartree-Fock (HF) ¿ ÒÌ Ò· Ú ´ÖµÒ´Öµ Ö Ú ¼ ¼ ½ Ò´ÖµÒ´Ö µ ¿ ¿ ¼ · Ö Ö · Ò Configuration-Interaction (CI) ¼ ¾ Ö Ö Quantum Monte-Carlo (QMC) ÑÒ Ò ¼ Ú Ê ¿ Ò´Ö µ ÖÆ Density-Functional Theory (DFT) ¼ ½ Ò´Ö µ ¾ ¿ ¼ ´ Ö · Ú ´Öµ· Ö · Ú ´Öµµ ´Öµ ´Öµ ¼ ¾ Ö Ö Æ Ò ¾ Ò´Öµ ´Öµ Ú ´Öµ Æ´Öµ Problem: Approximation to XC functional. decisions to make... Simulation of Atomic Geometries Example: chemisorption site & energy of a particular atom on a surface = ? How to simulate adsorption geometry? single molecule or cluster Use Bloch theorem. periodically repeated supercell, slab-geometry Efficient Brillouin zone integration schemes. true half-space geometry, Green-function methods decisions to make... Basis Set to Expand Wave-Functions ½ ¡Ê ´Øµ ´ Öµ Ù ´Ö Ê µ Ô Æ linear combination of Ê atomic orbitals (LCAO) ´ Öµ ´µ ´ Öµ simple, unbiased, ½ ´·µ¡Ö ´ Öµ ´ · µ plane waves (PW) Ô independent of ª atomic positions augmented plane waves . (APW) etc. etc. I. The Pseudopotential Concept Core-States and Chemical Bonding? Validity of the Frozen-Core Approximation U. von Barth, C.D. -

Car-Parrinello Molecular Dynamics

CPMD Car-Parrinello Molecular Dynamics An ab initio Electronic Structure and Molecular Dynamics Program The CPMD consortium WWW: http://www.cpmd.org/ Mailing list: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] January 29, 2019 Send comments and bug reports to [email protected] This manual is for CPMD version 4.3.0 CPMD 4.3.0 January 29, 2019 Contents I Overview3 1 About this manual3 2 Citation 3 3 Important constants and conversion factors3 4 Recommendations for further reading4 5 History 5 5.1 CPMD Version 1.....................................5 5.2 CPMD Version 2.....................................5 5.2.1 Version 2.0....................................5 5.2.2 Version 2.5....................................5 5.3 CPMD Version 3.....................................5 5.3.1 Version 3.0....................................5 5.3.2 Version 3.1....................................5 5.3.3 Version 3.2....................................5 5.3.4 Version 3.3....................................6 5.3.5 Version 3.4....................................6 5.3.6 Version 3.5....................................6 5.3.7 Version 3.6....................................6 5.3.8 Version 3.7....................................6 5.3.9 Version 3.8....................................6 5.3.10 Version 3.9....................................6 5.3.11 Version 3.10....................................7 5.3.12 Version 3.11....................................7 5.3.13 Version 3.12....................................7 5.3.14 Version 3.13....................................7 5.3.15 Version 3.14....................................7 5.3.16 Version 3.15....................................8 5.3.17 Version 3.17....................................8 5.4 CPMD Version 4.....................................8 5.4.1 Version 4.0....................................8 5.4.2 Version 4.1....................................8 5.4.3 Version 4.3....................................9 6 Installation 10 7 Running CPMD 11 8 Files 12 II Reference Manual 15 9 Input File Reference 15 9.1 Basic rules........................................ -

Qbox (Qb@Ll Branch)

Qbox (qb@ll branch) Summary Version 1.2 Purpose of Benchmark Qbox is a first-principles molecular dynamics code used to compute the properties of materials directly from the underlying physics equations. Density Functional Theory is used to provide a quantum-mechanical description of chemically-active electrons and nonlocal norm-conserving pseudopotentials are used to represent ions and core electrons. The method has O(N3) computational complexity, where N is the total number of valence electrons in the system. Characteristics of Benchmark The computational workload of a Qbox run is split between parallel dense linear algebra, carried out by the ScaLAPACK library, and a custom 3D Fast Fourier Transform. The primary data structure, the electronic wavefunction, is distributed across a 2D MPI process grid. The shape of the process grid is defined by the nrowmax variable set in the Qbox input file, which sets the number of process rows. Parallel performance can vary significantly with process grid shape, although past experience has shown that highly rectangular process grids (e.g. 2048 x 64) give the best performance. The majority of the run time is spent in matrix multiplication, Gram-Schmidt orthogonalization and parallel FFTs. Several ScaLAPACK routines do not scale well beyond 100k+ MPI tasks, so threading can be used to run on more cores. The parallel FFT and a few other loops are threaded in Qbox with OpenMP, but most of the threading speedup comes from the use of threaded linear algebra kernels (blas, lapack, ESSL). Qbox requires a minimum of 1GB of main memory per MPI task. Mechanics of Building Benchmark To compile Qbox: 1. -

Empirical Pseudopotential Method

Computational Electronics Empirical Pseudopotential Method Prepared by: Dragica Vasileska Associate Professor Arizona State University The Empirical Pseudopotential Method The concept of pseudopotentials was introduced by Fermi [1] to study high-lying atomic states. Afterwards, Hellman proposed that pseudopotentials be used for calculating the energy levels of the alkali metals [2]. The wide spread usage of pseudopotentials did not occur until the late 1950s, when activity in the area of condensed matter physics began to accelerate. The main advantage of using pseudopotentials is that only valence electrons have to be considered. The core electrons are treated as if they are frozen in an atomic-like configuration. As a result, the valence electrons are thought to move in a weak one-electron potential. The pseudopotential method is based on the orthogonalized plane wave (OPW) method due to Herring. In this method, the crystal wavefuntion ψ k is constructed to be orthogonal to the core states. This is accomplished by expanding ψ k as a smooth part of symmetrized combinations of Bloch functions ϕk , augmented with a linear combination of core states. This is expressed as ψ = ϕ + Φ k k ∑bk,t k,t , (1) t where bk,t are orthogonalization coefficients and Φ k,t are core wave functions. For Si-14, the summation over t in Eq. (1) is a sum over the core states 1s2 2s2 2p6. Since the crystal wave function is constructed to be orthogonal to the core wave functions, the orthogonalization coefficients can be calculated, thus yielding the final expression ψ = ϕ − Φ ϕ Φ k k ∑ k,t k k,t . -

Pseudopotential Theory of Semiconductor Quantum Dots Alex Zunger

phys. stat. sol. (b) 224, No. 3, 727–734 (2001) Pseudopotential Theory of Semiconductor Quantum Dots Alex Zunger National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Golden, CO 80401, USA (Received July 31, 2000; accepted October 2, 2000) Subject classification: 71.15.Dx; 73.21.La; S5.11; S5.12; S7.11; S7.12; S8.11; S8.12 This paper reviews our pseudopotential approach to study the electronic structure of semiconduc- tor quantum dots, emphasizing methodology ideas and a survey of recent applications to both “free-standing” and “semiconductor embedded” quantum-dot systems. 1. Introduction: What Are the Bottlenecks LimitingAccurate Theoretical Modelingof Semiconductor Quantum Dots Analyses of the experimental observations on quantum dots reveal that a theory of quantum dots must encompass both single-particle electro- nic structure and many-body physics. Regarding the single-particle electronic structure, the available methods are either insuf- ficient or impossibly complicated. The prevailing single-particle method for quantum nano- structures –– the effective-mass approximation (EMA) and its “k Á p” generalization –– were carefully tested by us [1–3], and were found to be insufficiently accurate for our purposes. Specifically, the underlying continuum-like EMA misses the atomistic nature of quantum dots. Indeed, in attempting to expand the dot’s wavefunction in terms of only the VBM and CBM of the infinite bulk solid at the Brillouin zone center (k = 0) the EMA produces but a rough sketch of the dot’s microscopic wavefunctions. The limited accuracy originating from the neglect of multi-band coupling prevents reliable calculations of wave- function expectation values such as energy levels [1–4], exchange energies [5] and inter- electronic Coulomb repulsion [6] in free-standing quantum dots. -

Quantum Espresso Intro Student Cluster Competition

SC21 STUDENT CLUSTER COMPETITION QUANTUM ESPRESSO INTRO STUDENT CLUSTER COMPETITION erhtjhtyhy YE LUO COLLEEN BERTONI Argonne National Laboratory Argonne National Laboratory Jun. 28th 2021 MANIFESTO § QUANTUM ESPRESSO is an integrated suite of Open-Source computer codes for electronic-structure calculations and materials modeling at the nanoscale. It is based on density-functional theory, plane waves, and pseudopotentials. § https://www.quantum-espresso.org/project/manifesto 2 SCIENCE, ALGORITHMS QUANTUM MECHANICS For microscopic material properties The picture can't be displayed. The picture can't be displayed. We solve this simplified case The picture can't be displayed. which is still extremely difficult 4 DENSITY FUNCTIONAL THEORY § Hohenberg–Kohn theorems – Theorem 1. The external potential (and hence the total energy), is a unique functional of the electron density. – Theorem 2. The functional that delivers the ground-state energy of the system gives the lowest energy if and only if the input density is the true ground-state density. § Kohn-Sham equation – The ground-state density of the interacting system of interest can be calculated as ground-state density of an auxiliary non-interacting system in an effective potential – Solvable with approximations, LDA 5 BOOMING PUBLICATIONS Highly correlated with the availability of HPC clusters Numbers of papers when DFT is searched as a topic Perspective on density functional theory K. Burke, J. Chem. Phys. 136, 150901 (2012) 6 MANY DFT CODES AROUND THE WORLD •Local orbital basis codes -

VASP: Basics (DFT, PW, PAW, … )

VASP: Basics (DFT, PW, PAW, … ) University of Vienna, Faculty of Physics and Center for Computational Materials Science, Vienna, Austria Outline ● Density functional theory ● Translational invariance and periodic boundary conditions ● Plane wave basis set ● The Projector-Augmented-Wave method ● Electronic minimization The Many-Body Schrödinger equation Hˆ (r1,...,rN )=E (r1,...,rN ) 1 1 ∆i + V (ri)+ (r1,...,rN )=E (r1,...,rN ) 0−2 ri rj 1 i i i=j X X X6 | − | @ A For instance, many-body WF storage demands are prohibitive: N (r1,...,rN ) (#grid points) 5 electrons on a 10×10×10 grid ~ 10 PetaBytes ! A solution: map onto “one-electron” theory: (r ,...,r ) (r), (r),..., (r) 1 N ! { 1 2 N } Hohenberg-Kohn-Sham DFT Map onto “one-electron” theory: N (r ,...,r ) (r), (r),..., (r) (r ,...,r )= (r ) 1 N ! { 1 2 N } 1 N i i i Y Total energy is a functional of the density: E[⇢]=T [ [⇢] ]+E [⇢]+E [⇢] + E [⇢]+U[Z] s { i } H xc Z The density is computed using the one-electron orbitals: N ⇢(r)= (r) 2 | i | i X The one-electron orbitals are the solutions of the Kohn-Sham equation: 1 ∆ + V (r)+V [⇢](r)+V [⇢](r) (r)=✏ (r) −2 Z H xc i i i ⇣ ⌘ BUT: Exc[⇢]=??? Vxc[⇢](r)=??? Exchange-Correlation Exc[⇢]=??? Vxc[⇢](r)=??? • Exchange-Correlation functionals are modeled on the uniform-electron-gas (UEG): The correlation energy (and potential) has been calculated by means of Monte- Carlo methods for a wide range of densities, and has been parametrized to yield a density functional. • LDA: we simply pretend that an inhomogeneous electronic density locally behaves like a homogeneous electron gas. -

Norm-Conserving Pseudopotentials with Chemical Accuracy Compared to All-Electron Calculations Alex Willand, Yaroslav O

Norm-conserving pseudopotentials with chemical accuracy compared to all-electron calculations Alex Willand, Yaroslav O. Kvashnin, Luigi Genovese, Álvaro Vázquez-Mayagoitia, Arpan Krishna Deb, Ali Sadeghi, Thierry Deutsch, and Stefan Goedecker Citation: The Journal of Chemical Physics 138, 104109 (2013); doi: 10.1063/1.4793260 View online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.4793260 View Table of Contents: http://scitation.aip.org/content/aip/journal/jcp/138/10?ver=pdfcov Published by the AIP Publishing Articles you may be interested in Electronic structure and optical conductivity of two dimensional (2D) MoS2: Pseudopotential DFT versus full potential calculations AIP Conf. Proc. 1447, 1269 (2012); 10.1063/1.4710474 Effects of d -electrons in pseudopotential screened-exchange density functional calculations J. Appl. Phys. 103, 113713 (2008); 10.1063/1.2936966 All-electron and relativistic pseudopotential studies for the group 1 element polarizabilities from K to element 119 J. Chem. Phys. 122, 104103 (2005); 10.1063/1.1856451 Norm-conserving Hartree–Fock pseudopotentials and their asymptotic behavior J. Chem. Phys. 122, 014112 (2005); 10.1063/1.1829049 The accuracy of the pseudopotential approximation. III. A comparison between pseudopotential and all-electron methods for Au and AuH J. Chem. Phys. 113, 7110 (2000); 10.1063/1.1313556 This article is copyrighted as indicated in the article. Reuse of AIP content is subject to the terms at: http://scitation.aip.org/termsconditions. Downloaded to IP: 131.152.108.241 On: Mon, 12 May 2014 14:50:15 THE JOURNAL OF CHEMICAL PHYSICS 138, 104109 (2013) Norm-conserving pseudopotentials with chemical accuracy compared to all-electron calculations Alex Willand,1 Yaroslav O. -

Architecture of Qbox, a Parallel, Scalable first- Principles Molecular Dynamics (FPMD) Code

IBM Journal of Research and Development Tuesday, 23 October 2007 3:53 pm Allen Press, Inc. ibmr-52-01-09 Page 1 Architecture of F. Gygi Qbox: A scalable first-principles molecular dynamics code We describe the architecture of Qbox, a parallel, scalable first- principles molecular dynamics (FPMD) code. Qbox is a Cþþ/ Message Passing Interface implementation of FPMD based on the plane-wave, pseudopotential method for electronic structure calculations. It is built upon well-optimized parallel numerical libraries, such as Basic Linear Algebra Communication Subprograms (BLACS) and Scalable Linear Algebra Package (ScaLAPACK), and also features an Extensible Markup Language (XML) interface built on the Apache Xerces-C library. We describe various choices made in the design of Qbox that lead to excellent scalability on large parallel computers. In particular, we discuss the case of the IBM Blue Gene/Le platform on which Qbox was run using up to 65,536 nodes. Future design challenges for upcoming petascale computers are also discussed. Examples of applications of Qbox to a variety of first-principles simulations of solids, liquids, and nanostructures are briefly described. Introduction consistently achieved a sustained performance of about First-principles molecular dynamics (FPMD) is an 50% of peak performance. atomistic simulation method that combines an accurate As a result of the need for simulations of increasing size description of electronic structure with the capability to and the availability of parallel computers, FPMD code describe dynamical properties by means of molecular design has been moving toward parallel implementations. dynamics (MD) simulations. This approach has met with In the 1990s and early 2000s, the FPMD community tremendous success since its introduction by Car and adapted to the change in computer architecture by Parrinello in 1985 [1].