Protein-Losing Nephropathy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

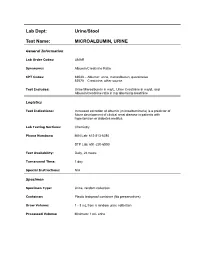

Lab Dept: Urine/Stool Test Name: MICROALBUMIN, URINE

Lab Dept: Urine/Stool Test Name: MICROALBUMIN, URINE General Information Lab Order Codes: UMAR Synonyms: Albumin/Creatinine Ratio CPT Codes: 82043 – Albumin: urine, microalbumin, quantitative 82570 – Creatinine; other source Test Includes: Urine Microalbumin in mg/L, Urine Creatinine in mg/dL and Albumin/creatinine ratio in mg albumin/g creatinine Logistics Test Indications: Increased excretion of albumin (microalbuminuria) is a predictor of future development of clinical renal disease in patients with hypertension or diabetes mellitus. Lab Testing Sections: Chemistry Phone Numbers: MIN Lab: 612-813-6280 STP Lab: 651-220-6550 Test Availability: Daily, 24 hours Turnaround Time: 1 day Special Instructions: N/A Specimen Specimen Type: Urine, random collection Container: Plastic leakproof container (No preservatives) Draw Volume: 1 - 3 mL from a random urine collection Processed Volume: Minimum: 1 mL urine Collection: A random urine sample may be obtained by voiding into a urine cup and is often performed at the laboratory. Bring the refrigerated container to the lab. Make sure all specimens submitted to the laboratory are properly labeled with the patient’s name, medical record number and date of birth. Special Processing: Lab Staff: Centrifuge specimen before analysis. Patient Preparation: Sample should not be collected after exertion, in the presence of a urinary tract infection, during acute illness, immediately after surgery, or after acute fluid load. Sample Rejection: Mislabled or unlabeled specimens; samples contaminated with blood Interpretive Reference Range: Albumin/creatinine ratio (A/C <30 mg/g Normal ratio) 30 - 299 mg/g Microalbuminuria >300 mg/g Clinical albuminuria Urine Creatinine: No reference ranges established Critical Values: N/A Limitations: Due to variability in urinary albumin excretion, at least two of three test results measured within a 6-month period should show elevated levels before a patient is designated as having microalbuminuria. -

Prevalence of Microalbuminuria and Associated Risk Factors Among Adult Korean Hypertensive Patients in a Primary Care Setting

Hypertension Research (2013) 36, 807–823 & 2013 The Japanese Society of Hypertension All rights reserved 0916-9636/13 www.nature.com/hr ORIGINAL ARTICLE Prevalence of microalbuminuria and associated risk factors among adult Korean hypertensive patients in a primary care setting Yon Su Kim 1, Han Soo Kim2, Ha Young Oh3, Moon-Kyu Lee4, Cheol Ho Kim5, Yong Soo Kim6,DavidWu6, Amy O Johnson-Levonas6 and Byung-Hee Oh7 Microalbuminuria is an early sign of nephropathy and an independent predictor of end-stage renal disease. The purpose of this study was to assess microalbuminuria prevalence and its contributing factors in Korean hypertensive patients. This cross-sectional study enrolled male and female patients of X35 years old with an essential hypertension diagnosis as made by 841 physicians in primary care clinics and 17 in general hospitals in the Republic of Korea between November 2008 and July 2009. To assess microalbuminuria prevalence, urine albumin/creatinine ratio (UACR) was measured in patients with a positive dipstick test. Of the 40 473 enrolled patients, 5713 (14.1%) had a positive dipstick test. Of 5393 patients with a positive dipstick test and valid UACR values, 2657 (6.6%) had significantly elevated UACR (X30 lgmgÀ1), 2158 (5.4%) had microalbuminuria (30 lgmgÀ1pUACR o300 lgmgÀ1) and 499 (1.2%) had macroalbuminuria (UACR X300 lgmgÀ1). Based on multivariate analysis, independent factors associated with elevated UACR included low adherence to antihypertensive medication (23% higher; P ¼ 0.042), poorly controlled blood pressure (BP; 38% higher for systolic BP/diastolic BP X130 mm Hg/X80 mm Hg; Po0.001), obesity (47% higher for body mass index (BMI) X25.0 kg m À2; Po0.001), age (17% lower and 58% higher for age categories 35–44 years (P ¼ 0.043) and 475 years (Po0.001), respectively) and a prior history of diabetes (151% higher; Po0.001) and kidney-related disease (71% higher; Po0.001). -

Screening for Microalbuminuria in Patients with Diabetes

Screening for Microalbuminuria in Patients with Diabetes Why? How? To identify patients with diabetic kidney disease (DKD). Test for microalbuminuria To distinguish DKD patients from diabetic patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) from other causes. The latter require further investigation and possibly different No clinical management. + for albumin Because markers of kidney damage are required to detect early stages of CKD. Yes Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) alone can only detect CKD stage 3 or worse. Condition that may invalidate* urine albumin excretion When? Yes Begin screening: No Treat and/or wait until No resolved. Repeat test. In type 1 diabetes – 5 years after diagnosis, then annually + for protein? In type 2 diabetes – at diagnosis, then annually Yes Repeat microalbuminuria test twice within 3-6 month period. Is it Microalbuminuria? Measure urinary albumin-creatinine ratio (ACR) Yes Rescreen No in a spot urine sample. 2 of 3 tests positive? in one year Category Spot (mg/g creatinine) Yes Normoalbuminuria <30 Microalbuminuria, begin treatment Microalbuminuria 30-300 Macroalbuminuria >300 * Exercise within 24 hours, infection, fever, congestive heart failure, marked hyperglycemia, pregnancy, marked hypertension, urinary tract infection, and hematuria. Screening for Microalbuminuria in Patients with Diabetes Is it DKD? CKD should be attributable to diabetes if: Macroalbuminuria is present; or Microalbuminuria is present: • in the presence of diabetic retinopathy • in type 1 diabetes of at least 10 years’ duration Albuminuria GFR (mL/min) CKD Stage* Normoalbuminuria Microalbuminuria Macroalbuminuria >60 1 + 2 At risk† Possible DKD DKD 30-60 3 Unlikely DKD‡ Possible DKD DKD <30 4 + 5 Unlikely DKD‡ Unlikely DKD DKD * Staging may be confounded by treatment because RAS blockade could render microalbuminuric patients normoalbuminuric and macroalbuminuric patients microalbuminuric. -

Sympathetic Overactivity Predicts Microalbuminuria in Pregnancy

Original Article DOI: 10.7860/JCDR/2018/36738.12412 Sympathetic Overactivity Predicts Section Biochemistry Microalbuminuria in Pregnancy INDER PAL KAUR1, SUKANYA GANGOPADHYAY2, KIRAN SINGH3, MAMTA TYAGI4, GAUTAM SARKAR5 ABSTRACT pregnancy-induced hypertension. Statistical analysis was done Introduction: Microalbuminuria is a frequent feature in with appropriate tests using Graphpad Prizm (version 7.04). pregnancy, as the latter is a state of haemodynamic changes Results: The level of urinary microalbumin was found to be and sympathetic overactivity. Both sympathetic overactivity {as high in the pregnant group. Albumin Creatinine Ratio (ACR) was measured by Heart Rate Variability (HRV)} and microalbuminuria raised in pregnancy (72.35±50.29 in third trimester, 84.48±52.61 are individually linked with hypertension. So, presence of these in second trimester and 17.59±6.19 in non-pregnant control conditions in pregnant women could be the reason for the group; p<0.001). The HRV study shows that sympathetic increasing prevalence of Pregnancy Induced Hypertension dominance is more during pregnancy as compared to non- (PIH)/Preeclampsia. pregnant (2.09±0.91 in pregnant and 1.04±0.65 in non-pregnant Aim: To measure HRV and urinary microalbumin excretion group). simultaneously in pregnant women. Conclusion: It was concluded that there is a neurogenic role Materials and Methods: In this hospital-based study, pregnant for the causation of microalbuminuria in pregnancy. As this women in 2nd and 3rd trimester were recruited along with age- condition predicts the development of pre-eclampsia/eclampsia matched controls. Their sympathetic activity and urinary in later pregnancy, all the methods targeting generalised stress albumin-creatinine ratio were recorded. -

Microalbuminuria: a Potential Marker for Adverse 2018; 2(5): 64-68 Obstetric and Fetal Outcome Received: 11-07-2018 Accepted: 12-08-2018 Dr

International Journal of Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2018; 2(5): 64-68 ISSN (P): 2522-6614 ISSN (E): 2522-6622 © Gynaecology Journal Microalbuminuria: A potential marker for adverse www.gynaecologyjournal.com 2018; 2(5): 64-68 obstetric and fetal outcome Received: 11-07-2018 Accepted: 12-08-2018 Dr. K Lavanyakumari, Dr. Sangeereni, Dr. S Sethupathy and Dr. Chithra S Dr. K Lavanyakumari Professor and Head, Department of Obstetrics and Abstract Gynaecology, Rajah Muthiah Background: Obstetric and perinatal outcome is an index of health in society. Various markers are being [12, 13] Medical College, Annamalai searched so as to increase the well being of mother and fetus in pregnancy. Several Studies have University, Chidambaram, revealed an association between microalbuminuria and obstetric outcome. Microalbuminuria can be used as Tamil Nadu, India prognostic marker in evaluation of gestational hypertension, preterm labour, GDM, PPROM, IUGR. Objective: This study was done to evaluate whether microalbuminuria which was evaluated at late second Dr. Sangeereni trimester could serve as marker for adverse obstetric and neonatal outcome. Lecturer, Department of Obstetrics Materials and Methods: A Prospective case control study was carried out on 150 people. Urine tested for and Gynaecology, Rajah Muthiah urine micro albumin and creatinine and ACR ratio was calculated. Among 150 pregnant women 27 were Medical College, Annamalai positive for microalbuminuria and were categorised as group A. Pregnant women without University, Chidambaram, microalbuminuria were considered as group B (controls). Both group A and group B were compared for Tamil Nadu, India obstetric outcomes. Results: Significant association found between group A and gestational hypertension and preterm labour. -

Microalbuminuria in Essential Hypertension

Journal of Human Hypertension (2002) 16 (Suppl 1), S74–S77 2002 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0950-9240/02 $25.00 www.nature.com/jhh Microalbuminuria in essential hypertension G Crippa Hypertension Unit, Department of Internal Medicine, Civil Hospital, Via Taverna 49, 29100 Piacenza, Italy Microalbuminuria (urinary albumin excretion equal to to blood pressure reduction, but angiotensin-converting 30–300 mg/24 h) is a reliable indicator of premature enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin-II-receptor antagon- cardiovascular mortality in diabetic patients and in the ists show an additional beneficial effect on urinary general population. In insulin-dependent and non-insu- albumin excretion. Whether the reduction of micro- lin-dependent diabetes mellitus microalbuminuria is a albuminuria obtained through pharmacological inter- marker of initial diabetic nephropathy and predicts the vention has favourable prognostic implications remain evolution toward renal insufficiency. In essential to be demonstrated. However, screening for micro- hypertension the clinical and prognostic role of micro- albuminuria is a relatively easy and inexpensive pro- albuminuria is more controversial. While it is a recog- cedure and reveals a potentially treatable abnormality. nised marker of cardiovascular complications and a Thus, considering that microalbuminuria identifies reliable predictor of ischaemic heart disease, its prog- hypertensive subjects at higher risk than standard, uri- nostic value on the risk of progressive renal alterations nary albumin excretion should be routinely measured in is still uncertain because no prospective studies, taking hypertensive patients and, in the presence of micro- microalbuminuria as a selection criterion and renal albuminuria, antihypertensive treatment should be insufficiency as an end point, are available. Blood intensified in order to obtain an optimal blood press- pressure control with antihypertensive drugs is ure control. -

An Approach to a Person with Proteinuria Or Microalbuminuria

CHAPTER An Approach to a Person with Proteinuria or Microalbuminuria 29 Ravikeerthy M “The ghosts of dead patients that haunt us do not includes lessthan 30 mg of albumin.2,4 ask why did not employ the latest fad of clinical This amount of urinary proteins can be detcted by the investigation. They ask us, why did not test my urine” dipstick testing.3 Proteinuria can be transient following Sir Robert Hutchison heavy exercise. Persistent proteinuria needs to be investigated. False positive and false negetive results Kidney plays an important role in maintaining body are possible in a dipstick test (Table 1). Conditions are as homeostasis by changing the composition of urine to follows: maintain electrolytes and acid-base levels and also got endocrine function which maintains metabolism.1 Proteinuria is classified into microalbuminuria and macroalbuminuria.5 Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is normally used to assess the kidney function which may not be useful in Microalbuminuria refers to a subclinical condition with many clinical settings. Abnormalities kidney function can increased urinary albumin excretion. By definition not only be the early sign of kidney disease but can also microalbuminuria is the excretion of albumin in urine reflect many systemic conditions. at rate of 20-200 mcg/min (30-300 mg/day) or albumin to creatinine ratio of 2.5 to 25 mg/mmol in males and 3.5- Normally plasma proteins crosses glomerular capillaries 35mg/mmol in females.National health and nutritional and mesangium without entering urinary space except a examination survey (NHANES)study revealed that the small portion of small density proteins which are excreted prevalence of microalbuminuria in age group of 6-80 into the tubules and are reabsorbed by the proximal renal years is 6.1% in male and 9.7% in females. -

The Generalized Aminoaciduria Seen in Patients with Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor-1 Mutations Is a Feature of All Patients with Diab

The Generalized Aminoaciduria Seen in Patients With Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor-1␣ Mutations Is a Feature of All Patients With Diabetes and Is Associated With Glucosuria Coralie Bingham,1 Sian Ellard,1 Anthony J. Nicholls,2 Charles A. Pennock,3 John Allen,3 Alan J. James,2 Simon C. Satchell,2 Maurice B. Salzmann,2 and Andrew T. Hattersley1 Hepatocyte nuclear factor-1␣ (HNF-1␣) mutations are the most common cause of maturity-onset diabetes of the young. HNF-1␣ homozygous knockout mice exhibit a epatocyte nuclear factor-1␣ (HNF-1␣) is a mem- renal Fanconi syndrome with glucosuria and general- ber of the homeodomain-containing superfam- ized aminoaciduria in addition to diabetes. We investi- ily of transcription factors (1–4). These factors gated glucosuria and aminoaciduria in patients with have a role in the tissue-specific regulation of HNF-1␣ mutations. Sixteen amino acids were measured H gene expression in a number of tissues, including liver, in urine samples from patients with HNF-1␣ mutations, kidney, intestine, and pancreatic islets (5). Heterozygous age-matched nondiabetic control subjects, and age- ␣ matched type 1 diabetic patients, type 2 diabetic pa- mutations in the gene encoding HNF-1 are the most tients, and patients with diabetes and chronic renal common cause of maturity-onset diabetes of the young failure. The HNF-1␣ patients had glucosuria at lower (MODY) (6). MODY is a subgroup of type 2 diabetes glycemic control (as shown by HbA1c) than type 1 and characterized by autosomal dominant inheritance and a type 2 diabetic patients, consistent with a lower renal young age of onset (7). -

Tubular Dysfunction and Microalbuminuria in Insulin Dependent Diabetes Bulging Fontanelles in Infants Without Meningitis

Correspondence 635 4Packe GE, Innes JA. Protective effect of BCG vaccination in Walton's study, a significant correlation was found be- infant Asians: a case-control study. Arch Dis Child 1988;63: tween HbAjc values and urinary a-1-microglobulin excre- 277-81. tion as well as between 24 hour glycosuria and urinary excretion of a-1-microglobulin. In poorly controlled dia- G E PACKE and J A INNES betics with duration of disease shorter than 10 years (group Birmingham Chest Clinic, A and B) urinary a-1-microglobulin excretion returned to Birmingham normal when metabolic control improved, while it re- mained high in children with duration of diabetes longer than 10 years (group C) (table). Albumin excretion rate was less than 15 tg/minute in all diabetic children during the study. Our data confirm that glycaemic control influences Tubular dysfunction and urinary excretion of a-1-microglobulin; however, despite microalbuminuria in insulin dependent good metabolic control, children with long duration of diabetes diabetes and without microalbuminuria show an increased excretion of a-1-microglobulin. Sir, Although diabetic kidney disease is primarily a In a recent paper by Walton et al investigating tubular glomerulopathy,3 we believe that impaired tubular func- function in diabetics, urinary a-1-microglobulin excretion tion is detectable earlier than glomerular damage. was found to be significantly higher in diabetic children compared with controls.' Using an enzyme immunoassay References (Imzyne a,-M, Fujirebio Inc) we obtained similar results. Walton C, Bodansky HJ, Wales JK, Forbes MA, Cooper EH. In 62 type 1 diabetics (38 girls), aged 3 to 21 years, with Tubular dysfunction and microalbuminuria in insulin dependent duration of disease from one week to 13 years, urinary diabetes. -

Pitfalls of Using Microalbuminuria As a Screening Tool to Identify Subjects with Increased Risk for Kidney and Cardiovascular Disease

Pitfalls of using microalbuminuria as a screening tool to identify subjects with increased risk for kidney and cardiovascular disease Results of the Unreferred Renal Insufficiency (URI) study and the Early Renal Impairment and Cardiovascular Assessment in Belgium study (ERICABEL). Arjan van der Tol Promotor: Prof. dr. Wim Van Biesen Co-promotor: Prof. dr. Raymond Vanholder Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of ‘Doctor in Health Sciences’ 2014 Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ....................................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 7 1.1 Preface ................................................................................................................................... 9 1.2. Normal renal handling of albuminuria ................................................................................. 11 1.3. Mechanisms of tubular and glomerular albuminuria ........................................................... 13 1.4. Albuminuria as a manifestation of chronic kidney disease ................................................. 18 1.5. Albuminuria as a manifestation of cardiovascular disease .................................................. 21 1.6. The prevalence of albuminuria ............................................................................................ 25 1.7. How to measure albuminuria .............................................................................................. -

Higher Levels of Albuminuria Within the Normal Range Predict Incident Hypertension

JASN Express. Published on June 25, 2008 as doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008010038 CLINICAL EPIDEMIOLOGY www.jasn.org Higher Levels of Albuminuria within the Normal Range Predict Incident Hypertension John P. Forman,* Naomi D.L. Fisher,† Emily L. Schopick,* and Gary C. Curhan* *Renal Division and Channing Laboratory and †Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Hypertension, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts ABSTRACT Higher levels of albumin excretion within the normal range are associated with cardiovascular disease in high-risk individuals. Whether incremental increases in urinary albumin excretion, even within the normal range, are associated with the development of hypertension in low-risk individuals is unknown. This study included 1065 postmenopausal women from the first Nurses’ Health Study and 1114 premenopausal women from the second Nurses’ Health Study who had an albumin/creatinine ratio Ͻ25 mg/g and who did not have diabetes or hypertension. Among the older women, 271 incident cases of hypertension occurred during 4 yr of follow-up, and among the younger women, 296 incident cases of hypertension occurred during 8 yr of follow-up. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to examine prospec- tively the association between the albumin/creatinine ratio and incident hypertension after adjustment for age, body mass index, estimated GFR, baseline BP, physical activity, smoking, and family history of hypertension. Participants who had an albumin/creatinine ratio in the highest quartile (4.34 to 24.17 mg/g for older women and 3.68 to 23.84 mg/g for younger women) were more likely to develop hypertension than those who had an albumin/creatinine ratio in the lowest quartile (hazard ratio 1.76 [95% confidence interval 1.21 to 2.56] and hazard ratio 1.35 [95% confidence interval 0.97 to 1.91] for older and younger women, respectively). -

The Value of Urinary Albumin to Urinary Specific Gravity Ratio in Detecting Microalbuminuria in Diabetic Patients

Kufa Med.Journal 2011.VOL.14.No.1 The Value of Urinary Albumin to Urinary Specific gravity ratio in detecting Microalbuminuria in Diabetic patients. Dr. Hussein Aziz Nasir M.B.CH.B/ C.A.B.M أه ا إ ا ا ل آ وإد ا ال ال داء ا ال ال داء ا ه ل ت داء ا ، وب و ل ذ اه . ات ر ا ال ا ا ا آ ا ال ا ب د ا ا ل ر ( ٤٠ ) ً اء ا دة داء ا ا ا ا اذار م ٢٠٠٩ ا اب م ٢٠٠٩ و ل ارا ا ا و ة ا اد ا ا ا ا آ ل ال ال داء ا. Abbreviations ACE=Angiotensin converting Enzyme ACR=Albumin Creatinine Ratio AOR= Albumin/Osmolality Ratio Sp.gr=Specific Gravity D.M=Diabetes Mellitus IBW=Ideal Body Weight. SIADH=Syndrome of Inappropriate Anti-diuretic Hormone ESRD=End Stage Renal Disease eGFR= estimated glomerular filtration rate Key Words: specific gravity, Albuminuria, Diabetes. Abstract Background and objective microalbuminuria is known to be harbinger of serious complications in diabetes mellitus. since medical intervention early in onset of microalbuminuria can de critical in reducing these adverse outcomes. it is widely agreed that diabetic patients should be screened for microalbuminuria. the study aim is to evaluate micral tests strips in conjunction with a urine specific gravity determination as a rapid and accurate method in detecting microalbuminuria in diabetic patients. Patients and methods 40 diabetic patients from diabetic center of Al Sader Hospital in Najaf city were included in this study From March 2009 to August 2009.