Outlaw Horses and the Spirit of Calgary in the Automobile Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1.4Oti a Week Ending A° 11`,4, 2° 2172 AI 16 Of, 21 26 .46 October 16, 1993 24M 25 No

November St, MON TVEWED TNU FR! SET WEEKLY 1 2345 6 Oct?"6De:oToo II $3.00 2. 7 8 91011 12 13 1993 ,TA',"° A vt,""" 1415 16171819 20 $2.80 plus .20 GST 22 23242526 27 5 61 9 21 Volume 58 No. 14 4 A4AS16 2829 30 1.4oti A Week Ending A° 11`,4, 2° 2172 AI 16 of, 21 26 .46 October 16, 1993 24m 25 No. 1 HIT BLIND MELON Blind Melon ANNE MURRAY Croonin' MELISSA ETHERIDGE Yes I Am LOADED Various Artists SMASHING PUMPKINS DREAMLOVER Siamese Dream Mariah Carey INNER CIRCLE Columbia Bad To The Bone SCORPIONS Face The Heat : JUDGEMENT NIGHT SOUNDTRACK Various Artists THE CURE Show EVERYBODY HURTS R.E.M. HIT PICK NAKED RAIN The Waltons PET SHOP BOYS LOVIN' ARMS Very COUNTRY Darden Smith ADDS SPIRIT OF THE WEST PINK CASHMERE Faithlift Prince RISE AGAIN CULTURE BEAT SUNDAY MORNING The Rankin Family Serenity Earth Wind & Fire SAY THE WORD DUFF McKAGAN ALL THAT SHE WANTS Joel Feeney Believe In Me Ace Of Base THIS OLD HOUSE REN & STIMPY WILD WORLD Lynne & The Rebels You Eediot Mr. Big FALLIN' NEVER FELT SO GOOD: HEAL IT UP REBA McENTIRE THE MOMENT YOU WERE MINE . Shawn Camp Concrete Blonde Greatest Hits Volume Two Beth Neilsen Chapman I.R.S. RUNAWAY ALBUM PICK No. 1 ALBUM EnVogueOVE THE WISH Mae M000re ART OF LIVING The Boomers POSSESSIONS MAKE LOVE TO ME Sarah McLachlan Anne Murray AND IF VENICE IS SINKING SEND ME A LOVER Spirit Of The West Taylor Dayne RUBBERBAND GIRL LET ME SHOW YOU Kate Bush Dan Hill ,k I BELIEVE FULLY COMPLETELY CANDY DULFER Robert Plant DANCE MIX '93 The Tragically Hip Sax -A -Go -Go Various Artists MR. -

Download Annual Report

FORT CALGARY ANNUAL REPORT 2016 This is Where the Story Starts “GREAT CANADIAN DREAM NO. 4” JOANE CARDINAL-SCHUBERT “GREAT TITLE — 2 — TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAIRMAN AND CEO REPORT ................................................................................................................................................................. 2 BUSINESS PLAN – YEAR IN REVIEW ....................................................................................................................................................... 3 – 8 DONORS – OPERATING FUND, CAPITAL FUND AND MAKE HISTORY FUND ..................................................................................................... 9 SOURCES OF FUNDING .......................................................................................................................................................................... 10 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS ........................................................................................................................................................................ 11 – 12 FORT CALGARY’S BRAND The confluence of the Bow and Elbow Rivers is a significant place. Known to the Blackfoot as Moh’Kinsstis, the confluence has special meaning to the Siksika – it is the place where A wonderful Napi created people, tracing its history to the very origins of humanity. This site is at the representation of heart of traditional Blackfoot territory and was important to other Indigenous peoples who history and culture. came here to hunt, camp and cross the -

Corinne Jeffery

your guide to Western Canadian Historywith Alberta Books 2014 The Book Publishers Association of Alberta (BPAA) is proud to present Your Guide to Western Canadian History with Alberta Books. Approximately 15 Alberta-based publishers actively develop, print, and distribute history-oriented books. As a collective, they provide an invaluable service to the Alberta community, and also chronicle and provide critical historical analyses of people and places throughout Canada and the world. Unwritten history can fall by the wayside as time goes on. History books provide a repository of facts, ideas for the future, a resource for discussion and critical thought. They also help us understand people and societies. The BPAA takes great pleasure in introducing you to the many excellent history books being published in Alberta. We hope that you will be inspired to add these titles to your collections. Best regards, Kieran Leblanc Executive Director, Book Publishers Association of Alberta March, 2014 C atalogue legend available to purchase in bookstores illustrations or photographs included available from chapters.indigo.ca electronic format available to download available from amazon.ca special purchase discount available t Hank you to our funders Design by natalie Olsen, Kisscut Design Contents Alberta Place Names Here Is Where We Disembark page 2 All of Baba’s Children 11 A History of Art in Alberta, 1905–1970 Arctic Hell-Ship I Once Was a Cowboy Arriving: 1909–1919 Looking Back 3 Art Inspired by the Canadian Rockies 12 Louis Riel Baba’s Kitchen -

MEDIA RELEASE for IMMEDIATE RELEASE Celebrate

MEDIA RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Celebrate Alberta’s Multiculturalism at Glenbow Museum Calgary, AB (May 9, 2005) – Beginning July 1, 2005, Glenbow Museum’s entire second floor will be transformed into a rich celebration of Southeast Asian culture, with specific focus on the regions of Southern China, including Hong Kong, Indo-China (Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia), as well as Thailand. Glenbow’s summer 2005 show, Voices of Southeast Asia on from July 1, 2005 to September 25, 2005, will comprise of four exhibits that examine the vibrant culture of Southeast Asia from both historical and contemporary contexts. The feature exhibit, Vietnam: Journeys of Body, Mind & Spirit from the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, will examine the rich customs and traditions of Vietnam through colourful objects such as masks, textiles, ceramics and rich photographs. Seven Stories, will share the personal stories of seven immigrants who left their homeland to begin new lives in Canada. Foreign and Familiar: Reconsidering the Everyday is a contemporary art exhibit featuring the works of first generation Asian- Canadian artists who reconsider everyday objects and how they shape the way we see the world and each other. Finally, we will showcase Glenbow Museum’s magnificent permanent Asian gallery, Many Faces, Many Paths: Art of Asia with over eighty world-class sculptures including rare pieces from Cambodia, China, and Thailand symbolizing ancient religions and mythologies. According to Glenbow Museum President and CEO Mike Robinson, Voices of Southeast Asia was developed by taking a collaborative approach. Curators, designers, and programmers worked with Canada’s Asian artists and communities to share the various artistic voices and cultural perspectives of our Canadian mosaic – of particular importance during Alberta’s Centennial year. -

The Band That Became Spirit of the West Began As a Folk Trio Called Evesdropper in Vancouver Nearly 30 Years Ago. 13 Albums

The band that became Spirit of the West began as a Folk trio called Evesdropper in Vancouver nearly 30 years ago. 13 albums later, they have achieved status as one of the most beloved ‘Legacy Artists’ in Canadian history, having proven themselves to be road-worthy, durable, having toured Canada, the US, UK and Europe consistently, building a dedicated following of fans from all over the world. They have been inducted into the Halls of Fame / Lifetime Achievement Categories by the Western Canadian Music Association and the Society of Composers and Music Publishers of Canada, and have used their inestimable charms to wheedle complimentary pints out of barmen in at least 9 countries. With four gold and two platinum albums to their credit, Spirit of the West are responsible for such songs as: ‘(And if) Venice is Sinking’, ‘Five Free Minutes’, ‘Save This House’, ‘The Crawl’ and ‘Home For a Rest’, the song that has been called Canada’s honorary national anthem:. ‘Spirituality: A Consummate Compendium’, a double CD album on Rhino Records, is the band’s most recent release and is a look back at the first 25 years of their career. The band is: John Mann, Guitarist, vocalist and charismatic front man. John is also an accomplished actor who can be seen on episodic television and movies often pretending to be an assassin, ghost, devil, redneck, spy, and other characters that simply don’t scan if you know this vegetarian peacenik. List of both big & small screen appearances as well as starring roles in live theatre far too numerous to mention here. -

DAVEANDJENN Whenever It Hurts

DAVEANDJENN Whenever It Hurts January 19 - February 23, 2019 Opening: Saturday January 19, 3 - 6 pm artists in attendance detail: “Play Bow” In association with TrépanierBaer Gallery, photos by: M.N. Hutchinson GENERAL HARDWARE CONTEMPORARY 1520 Queen Street West, Toronto, M6R 1A4 www.generalhardware.ca Hours: Wed. - Sat., 12 - 6 pm email: [email protected] 416-821-3060 DaveandJenn (David Foy and Jennifer Saleik) have collaborated since 2004. Foy was born in Edmonton, Alberta in 1982; Saleik in Velbert, Germany, in 1983. They graduated with distinction from the Alberta College of Art + Design in 2006, making their first appearance as DaveandJenn in the graduating exhibition. Experimenting with form and materials is an important aspect of their work, which includes painting, sculpture, installation, animation and digital video. Over the years they have developed a method of painting dense, rich worlds in between multiple layers of resin, slowly building up their final image in a manner that is reminiscent of celluloid animation, collage and Victorian shadow boxes. DaveandJenn are two times RBC Canadian Painting Competition finalists (2006, 2009), awarded the Lieutenant Governor of Alberta’s Biennial Emerging Artist Award (2010) and longlisted for the Sobey Art Award (2011). DaveandJenn’s work was included in the acclaimed “Oh Canada” exhibition curated by Denise Markonish at MASS MoCA – the largest survey of contemporary Canadian art ever produced outside of Canada. Their work can be found in both private and public collections throughout North America, including the Royal Bank of Canada, the Alberta Foundation for the Arts, the Calgary Municipal Collection and the Art Gallery of Hamilton. -

Connaught School | Approved Fees

Approved School Fees 2021-22 Connaught School If your child participates in any of the activities, field trips, items or services listed, you are responsible for paying those fees. A convenient and secure way to pay is online at www.cbe.ab.ca/mycbe. Learn more at www.cbe.ab.ca/fees-faq. Fees and Charges Approved Field Trip - Active Living - Swimming 30.00 Field Trip - Camp Experience - Rivers Edge Camp 20.00 Field Trip - Camp Experience - YMCA Outdoor School 300.00 Field Trip - Culinary Experience - ATCO Blue Flame Kitchen 10.00 Field Trip - Cultural Experience - Heritage Park 15.00 Field Trip - Cultural Experience - Lougheed House 12.00 Field Trip - Fine Arts Experience - Leighton Art Centre 25.00 Field Trip - Fine Arts Experience - Studio Bell 15.00 Field Trip - Fine Arts Experience - Young Writers' Conference 50.00 Field Trip - Museum Experience - Fort Calgary 20.00 Field Trip - Museum Experience - Glenbow Museum 20.00 Field Trip - Science Experience - Ann & Sandy Cross Conservation Area 30.00 Field Trip - Science Experience - Bow Habitat Station 15.00 Field Trip - Science Experience - Calgary Zoo 30.00 Field Trip - Science Experience - Fish Creek Park 15.00 Field Trip - Science Experience - Inglewood Bird Sanctuary 15.00 Field Trip - Science Experience - Interactions and Ecosystems Field Study 300.00 Field Trip - Science Experience - Nose Hill Park 12.00 Field Trip - Science Experience - Ralph Klein Park 20.00 Field Trip - Science Experience - St Patrick's Island Park 12.00 Field Trip - Science Experience - Telus Spark 15.00 Field -

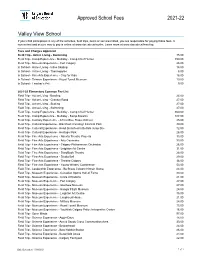

Valley View School | Approved Fees

Approved School Fees 2021-22 Valley View School If your child participates in any of the activities, field trips, items or services listed, you are responsible for paying those fees. A convenient and secure way to pay is online at www.cbe.ab.ca/mycbe. Learn more at www.cbe.ab.ca/fees-faq. Fees and Charges Approved Field Trip - Active Living - Swimming 35.00 Field Trip - Camp Experience - Multiday - Camp Chief Hector 350.00 Field Trip - Museum Experience - Fort Calgary 28.00 In School - Active Living - Inline Skating 18.00 In School - Active Living - Thermopylae 8.00 In School - Fine Arts Experience - Clay for Kids 18.00 In School - Science Experience - Royal Tyrrell Museum 10.00 In School - Teacher's Pet 9.00 2021-22 Elementary Common Fee List Field Trip - Active Living - Bowling 24.00 Field Trip - Active Living - Granary Road 27.00 Field Trip - Active Living - Skating 27.00 Field Trip - Active Living - Swimming 47.00 Field Trip - Camp Experience - Multiday - Camp Chief Hector 360.00 Field Trip - Camp Experience - Multiday - Kamp Kiwanis 387.00 Field Trip - Culinary Experience - ATCO Blue Flame Kitchen 25.00 Field Trip - Cultural Experience - Blackfoot Crossing Historical Park 39.00 Field Trip - Cultural Experience - Head Smashed in Buffalo Jump Site 72.00 Field Trip - Cultural Experience - Heritage Park 26.00 Field Trip - Fine Arts Experience - Alberta Theatre Projects 33.00 Field Trip - Fine Arts Experience - Arts Commons 33.00 Field Trip - Fine Arts Experience - Calgary Philharmonic Orchestra 26.00 Field Trip - Fine Arts Experience -

Thank You! CEO & CHAIR MESSAGE

2019/20 Thank you! FOR HELPING US TO EXPAND OUR SERVICES AND INSPIRE ACTION. ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL CEO & CHAIR MESSAGE Thanks to your generous support, we’ve been busy this past year! Cathy Barrick Keith Gibbons Chief Executive Officer Board Chair Alzheimer Society Alzheimer Society of Ontario of Ontario This past year has been full of exciting achievements dementia-specific trained staff possible. We have and progress in many areas. I am proud of the worked to develop a U-First!® for families program, Alzheimer Society of Ontario team’s work on our funded by the generous support of Grant and Alice strategic priorities – they have been working hard and Burton. This program will assist care partners across making things happen! Ontario. We continue to enhance and grow our First Link® Care We have welcomed some very special donors to our Navigation program across the province. With funding Alzheimer Society family – with incredible gifts to support from the Ministry of Health, this program help us create more programming opportunities and provides critical support to thousands of Ontarians to support research. Special thanks to Tiina Walker, whose lives have been touched by dementia. Our Catherine Booth, Michael Kirk and Brent Allen who Finding Your Way program has leveraged partnerships lead the way with their generosity. with first responders across the province to ensure that people living with dementia can live safely in their Thanks to all our partners, stakeholders, donors and communities – thanks to funding from the Ministry clients – our work is a privilege and we look forward to for Seniors and Accessibility. -

GLENBOW RTTC.Pdf

2012–13 Report to the Community REPORT TO THE COMMUNITY 2012–13 Contents 1 Glenbow by the Numbers 2 Message from the President and Chair 4 Exhibitions 6 Events and Programs 8 Collections and Acquisitions 10 Support from the Community 12 Thank You to Our Supporters 14 Volunteers at Glenbow 15 Board of Governors 16 Management and Staff About Us In 1966, the Glenbow-Alberta Institute the Province of Alberta have worked was created when Eric Harvie and his together to preserve this legacy for future family donated his impressive collection generations. We gratefully acknowledge of art, artifacts and historical documents the Province of Alberta for its ongoing to the people of Alberta. We are grateful support to enable us to care for, maintain for their foresight and generosity. In and provide access to the collections the last four decades, Glenbow and on behalf of the people of Alberta. Glenbow Byby the Numbers 01 Library & Archives Operating Fund Operating Fund researchers served Revenue Expenditures 5% 9% 11% 6% 33% 32% 9% 7,700 19% 22% 9% 20% 25% Amortization of Deferred Depreciation & Revenue (Property & Amortization - $919,818 43,072 Equipment) - $493,443 Total in-house and outreach Commercial Library & Archives - $534,838 Activities - $1,032,498 education program participants Commercial Activities Admissions & & Fundraising - $1,891,010 Memberships - $859,785 Collections Miles that artwork for the Fundraising- $2,068,248 Management - $923,889 Programs & Exhibition Charlie Russell exhibition travelled Investment Development - $2,422,362 Income - $1,849,922 Government Central Services - $3,184,154 of Alberta - $3,176,000 Audited fi nancial statements for the year ended March 31, 2013 8,000 can be found at www.glenbow.org 108 Rubbermaid totes 117,681 used in Iain BAAXTERXTER&’s installation Shelf Life Total Attendance Number of artifacts and 797 works of art treated by Charlie Russell Glenbow conservation staff exhibition catalogues sold in the Glenbow Museum Shop 220 02 REPORT TO THE COMMUNITY 2012–13 Message from the Donna Livingstone R. -

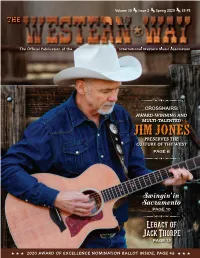

Spring 2020 $5.95 THE

Volume 30 Issue 2 Spring 2020 $5.95 THE The Offi cial Publication of the International Western Music Association CROSSHAIRS: AWARD-WINNING AND MULTI-TALENTED JIM JONES PRESERVES THE CULTURE OF THE WEST PAGE 6 Swingin’ in Sacramento PAGE 10 Legacy of Jack Thorpe PAGE 12 ★ ★ ★ 2020 AWARD OF EXCELLENCE NOMINATION BALLOT INSIDE, PAGE 46 ★ ★ ★ __WW Spring 2020_Cover.indd 1 3/18/20 7:32 PM __WW Spring 2020_Cover.indd 2 3/18/20 7:32 PM 2019 Instrumentalist of the Year Thank you IWMA for your love & support of my music! HaileySandoz.com 2020 WESTERN WRITERS OF AMERICA CONVENTION June 17-20, 2020 Rushmore Plaza Holiday Inn Rapid City, SD Tour to Spearfish and Deadwood PROGRAMMING ON LAKOTA CULTURE FEATURED SPEAKER Virginia Driving Hawk Sneve SESSIONS ON: Marketing, Editors and Agents, Fiction, Nonfiction, Old West Legends, Woman Suffrage and more. Visit www.westernwriters.org or contact wwa.moulton@gmail. for more info __WW Spring 2020_Interior.indd 1 3/18/20 7:26 PM FOUNDER Bill Wiley From The President... OFFICERS Robert Lorbeer, President Jerry Hall, Executive V.P. Robert’s Marvin O’Dell, V.P. Belinda Gail, Secretary Diana Raven, Treasurer Ramblings EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Marsha Short IWMA Board of Directors, herein after BOD, BOARD OF DIRECTORS meets several times each year; our Bylaws specify Richard Dollarhide that the BOD has to meet face to face for not less Juni Fisher Belinda Gail than 3 meetings each year. Jerry Hall The first meeting is usually in the late January/ Robert Lorbeer early February time frame, and this year we met Marvin O’Dell Robert Lorbeer Theresa O’Dell on February 4 and 5 in Sierra Vista, AZ. -

Capitol Hill School

Approved School Fees 2021-22 Capitol Hill School If your child participates in any of the activities, field trips, items or services listed, you are responsible for paying those fees. A convenient and secure way to pay is online at www.cbe.ab.ca/mycbe. Learn more at www.cbe.ab.ca/fees-faq. Fees and Charges Approved Field Trip - Active Living - Skiing 110.00 Field Trip - Active Living - Swimming 35.00 Field Trip - Camp Experience - Multi Day 400.00 Field Trip - Cultural Experience - Heritage Park 20.00 Field Trip - Fine Arts Experience - Studio Bell 25.00 Field Trip - Fine Arts Experience - Theatre Performance 35.00 Field Trip - Fine Arts Experience - Young Writers' Conference 50.00 Field Trip - Museum Experience - Glenbow Museum 15.00 Field Trip - Museum Experience - Hangar Flight Museum 15.00 Field Trip - Museum Experience - Leighton Art Centre 30.00 Field Trip - Museum Experience - Youthlink Calgary Police Interpretive Centre 8.00 Field Trip - Science Experience - Aggie Days 8.00 Field Trip - Science Experience - Bow Habitat Station 20.00 Field Trip - Science Experience - Butterfield Acres 20.00 Field Trip - Science Experience - Calgary Waste Management Facility 20.00 Field Trip - Science Experience - Calgary Zoo 30.00 Field Trip - Science Experience - Inglewood Bird Sanctuary 30.00 Field Trip - Science Experience - Nose Hill Park 8.00 Field Trip - Science Experience - Ralph Klein Park 15.00 Field Trip - Science Experience - Telus Spark 20.00 Field Trip - Science Experience - Weaselhead Flats 15.00 Field Trip - Science Experience -