A Future for Northern Ireland's Built Heritage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

11 April 2018 Dear Councillor You Are Invited to Attend a Meeting of the Development Committee to Be Held in the Chamber, Magher

11 April 2018 Dear Councillor You are invited to attend a meeting of the Development Committee to be held in The Chamber, Magherafelt at Mid Ulster District Council, Ballyronan Road, MAGHERAFELT, BT45 6EN on Wednesday, 11 April 2018 at 19:00 to transact the business noted below. Yours faithfully Anthony Tohill Chief Executive AGENDA OPEN BUSINESS 1. Apologies 2. Declarations of Interest 3. Chair's Business Matters for Decision 4. Economic Development Report 3 - 34 5. CCTV for Park N Rides 35 - 36 6. Community Grants 37 - 64 7. Mid Ulster District Council Every Body Active 2020 65 - 94 8. Innevall Railway Walk, Stewartstown 95 - 98 9. Lough Neagh Rescue - SLA 99 - 102 10. Special Events on Roads Legislation 103 - 104 Matters for Information 11 Development Committee Minutes of Meeting held on 105 - 120 Thursday 15 March 2018 12 Mid Ulster Tourism Development Group 121 - 126 13 Parks Service Progress/Update Report 127 - 138 14 Culture & Arts Progress Report 139 - 186 Items restricted in accordance with Section 42, Part 1 of Schedule 6 of the Local Government Act (NI) 2014. The public will be asked to withdraw from the meeting at this point. Matters for Decision Page 1 of 186 15. Community Development Report 16. Leisure Tender - Supply of Fitness Equipment Maintenance and Servicing Matters for Information 17. Confidential Minutes of Development Committee held on Thursday 15 March 2018 Page 2 of 186 1) LED Outdoor Mobile Screens 2) NI Women’s Enterprise Challenge Proposal 2018- 21 3) Maghera Town Centre Forum 4) Village Renewal Project Report on 5) Coalisland Public Realm 6) Hong Kong Trade Visit 7) Local Full Fibre Network (LFFN) Challenge Fund 8) International Women’s Day Events 9) World Butchers Challenge Event Reporting Officer Fiona McKeown, Head of Economic Development Is this report restricted for confidential business? Yes If ‘Yes’, confirm below the exempt information category relied upon No X 1.0 Purpose of Report 1.1 To provide Members with an update on key activities as detailed above. -

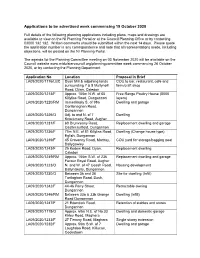

Planning Applications Advertised Week Commencing 19 October 2020

Applications to be advertised week commencing 19 October 2020 Full details of the following planning applications including plans, maps and drawings are available to view on the NI Planning Portal or at the Council Planning Office or by contacting 03000 132 132. Written comments should be submitted within the next 14 days. Please quote the application number in any correspondence and note that all representations made, including objections, will be posted on the NI Planning Portal. The agenda for the Planning Committee meeting on 03 November 2020 will be available on the Council website www.midulstercouncil.org/planningcommittee week commencing 26 October 2020, or by contacting the Planning Department. Application No Location Proposal in Brief LA09/2020/1176/LBC Dyan Mill & adjoining lands COU to bar, restaurant, cafe and surrounding 7 & 9 Mullyneill farm/craft shop Road, Dyan, Caledon LA09/2020/1213/F Approx. 150m N.W. of 65 Free Range Poultry House (8000 Killyliss Road, Dungannon layers) LA09/2020/1220/RM Immediately S. of 98a Dwelling and garage Gortlenaghan Road, Dungannon LA09/2020/1226/O Adj. to and N. of 7 Dwelling Knockmany Road, Augher LA09/2020/1231/F 60 Drumreany Road, Replacement dwelling and garage Castlecaulfield, Dungannon LA09/2020/1236/F 75m N.E. of 81 Killyliss Road, Dwelling (Change house type) Eglish, Dungannon LA09/2020/1239/F 45 Cravenny Road, Martray, COU yard for storage/bagging peat Ballygawley LA09/2020/1243/F 25 Kedew Road, Dyan, Replacement dwelling Caledon LA09/2020/1249/RM Approx. 100m S.W. of 236 Replacement dwelling and garage Favour Royal Road, Augher LA09/2020/1223/O N. -

Northern Ireland) 1988

554 Agriculture No. 91 1988 No. 91 AGRICULTURE Environmentally Sensitive Areas (Mourne Mountains and Slieve Croob) Designation Order (Northern Ireland) 1988 Made 21st March 1988 Coming into operation 1st May 1988 Whereas, in accordance with Article 3(1) of the Agriculture (Environmental Areas) (Northern Ireland) Order 1987(a), it appears to the Department of Agriculture that it is particularly desirable- (1) to conserve and enhance the natural beauty of the area referred to in Article 3; . (2) to conserve the flora and fauna and geological and physiographical features of that area; and (3) to protect buildings and other objects of historic interest in that .area; And whereas, in accordance with the said Article 3(1) ofthe said Order it appears to the Department that the maintenance and adoption of the agricultural methods specified in the Schedule is likely to facilitate the aforementioned conservation, enhancement and protection; Now, therefore, the Department, in exercise of the powers conferred on it by Article 3(1) and (3) ofthe said Order, and of every other power enabling it in that behalf, with the consent of the Department of Finance and Personnel hereby makes the following Order:- Citation and commencement 1. This Order may be cited as the Environmentally Sensitive Areas (Mourne Mountains and Slieve Croob) Designation Order (Northern Ireland) 1988 and shall come into operation on 1st May 1988. Interpretation 2. In this Order- "agreement" means an agreement under Article 3(2) of the Agriculture (Environmental Areas) (Northern Ireland) Order 1987 as respects· agricultural land in the area designated by Article 3; "conservation plan" means a layout plan of the farm and an attached statement identifying relevant land and conservation features and setting out, as appropriate, details of how the requirements in the agreement will be implemented on the farm; "tbe Department" means the Department of Agriculture; (a) S.!. -

Outdoor Recreation Action Plan for the Sperrins (ORNI on Behalf of Sportni, 2013)

Mid Ulster District Council Outdoor Recreation Strategic Plan Prepared by Outdoor Recreation NI on behalf of Mid Ulster District Council October 2019 CONTENTS CONTENTS ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 TABLE OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................................................... 6 TABLE OF TABLES ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 ACRONYMS ........................................................................................................................................................ 6 FOREWORD ........................................................................................................................................................ 7 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................................... 8 1.1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................12 1.2 Aim ....................................................................................................................................................12 1.3 Objectives .........................................................................................................................................13 -

Slieve Croob Walk Leaflet

Slieve Croob – Transmitter Road and ‘Pass Loanin’ 2 Walk Combinations in Dromara Hills FACT FILE Introduction Walks located in the open countryside of the Distances: Dromara Hills in the Mourne/Slieve Croob Area of Approx. (1) 2.4 miles or (2) 6.5 miles. Outstanding Natural Beauty: Walk (1) is a linear walk along a metalled road Grade: Moderate – Stiles to climb at summit. Walk (1) Gradual climb to the which leads to the summit of Slieve Croob (534 summit but with some steep ascents. m/1755 ft). If you are not a hill walker this walk can be a bit of a slog but Walk (2) Ditto but takes in open mountain. the views make it worth while. It takes about 30 mins at a moderate pace to walk to the top of the mountain – just over a mile and there are a Advice: couple of stiles to negotiate at the top. The summit is marred by ugly No dogs. Pedestrian access only.The top of the mountain is exposed and can be very communication masts but the access road to these masts provides windy. Only attempt Walk (2) in clear an easy means of access on foot to the weather when the waymark posts are mountain. On a clear day the Galloway coast clearly visible. Boggy and wet areas – boots of Scotland and the Isle of Man can be seen recommended. and there are great views towards the Mournes and across NI. The River Start and Finish: Walk (1): Dree Hill Car Park. Lagan rises on Slieve Croob (as the climb gets Walk (2):‘Peter Morgan’s Cottage’ at Finnis. -

The Down Rare Plant Register of Scarce & Threatened Vascular Plants

Vascular Plant Register County Down County Down Scarce, Rare & Extinct Vascular Plant Register and Checklist of Species Graham Day & Paul Hackney Record editor: Graham Day Authors of species accounts: Graham Day and Paul Hackney General editor: Julia Nunn 2008 These records have been selected from the database held by the Centre for Environmental Data and Recording at the Ulster Museum. The database comprises all known county Down records. The records that form the basis for this work were made by botanists, most of whom were amateur and some of whom were professional, employed by government departments or undertaking environmental impact assessments. This publication is intended to be of assistance to conservation and planning organisations and authorities, district and local councils and interested members of the public. Cover design by Fiona Maitland Cover photographs: Mourne Mountains from Murlough National Nature Reserve © Julia Nunn Hyoscyamus niger © Graham Day Spiranthes romanzoffiana © Graham Day Gentianella campestris © Graham Day MAGNI Publication no. 016 © National Museums & Galleries of Northern Ireland 1 Vascular Plant Register County Down 2 Vascular Plant Register County Down CONTENTS Preface 5 Introduction 7 Conservation legislation categories 7 The species accounts 10 Key to abbreviations used in the text and the records 11 Contact details 12 Acknowledgements 12 Species accounts for scarce, rare and extinct vascular plants 13 Casual species 161 Checklist of taxa from county Down 166 Publications relevant to the flora of county Down 180 Index 182 3 Vascular Plant Register County Down 4 Vascular Plant Register County Down PREFACE County Down is distinguished among Irish counties by its relatively diverse and interesting flora, as a consequence of its range of habitats and long coastline. -

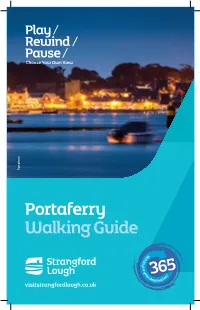

Portaferry Walking Guide

Portaferry Portaferry Walking Guide visitstrangfordlough.co.uk BElfastOWN AR& DS Portaferry NEWT oad h R ac Map Co t Anne Street e re t S h 6 OUGHEY rc CL u h C Aquarium 5 Ashmount The Square 2 High Street 1 4 Meeting Hou 16 3 Sho 15 e St re R se Lane d Castl 8 7 y St 13 14 r er F Strangford 12 Ballyphilip Road Ferry 9 Terminal 11 Steel Dickson Av Marina 18 10 W indmill Hill VIEWPOINT WINDMILL Sho 17 r e R d STRANGFORD LOUGH eet e Str Cook Sho r e R 1 Portaferry Castle and d Visitor Information Centre Cooke 2 The Northern Ireland Aquarium Street 3 Credit Union Jetty 4 Market House 5 St Cooey’s Oratory 6 Ballyphilip Parish Church and Temple Craney Graveyard 7 National School 8 The Presbyterian Church and Portico 9 Steel Dickson Avenue 10 Joseph Tomelty Blue Plaque 11 Blaney’s Shop 12 Dumigan’s Pub 13 Methodist Church 14 The Watcher 15 RNLI Lifeboat Station 16 Queens University and Belfast Marine Laboratory Additional Route (Follow Arrows) 17 The View Point Additional Route Please note that this map is not 18 Tullyboard Windmill to scale and is for reference only Portaferry Walking Guide Historical Walking Trail of Portaferry, Co Down The main route consists of flat The tour will last approximately concrete footpaths with pedestrian one hour. For your convenience, crossing opportunities. Please be there are also public toilets and a aware when crossing the road and wide range of cafes and restaurants keep an eye out for traffic at all times. -

Produced by Outdoor Recreation NI on Behalf of Mid Ulster District Council

PUBLIC PARKS AND PLAY FIVE YEAR STRATEGIC PLAN 2019 - 2024 September 2018 Produced by Outdoor Recreation NI on behalf of Mid Ulster District Council CONTENTS ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................................................. 6 FOREWORD ............................................................................................................................................. 7 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................ 8 BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................... 19 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 19 Aim ........................................................................................................................................ 20 Objectives.............................................................................................................................. 20 SCOPE ............................................................................................................................................ 21 Project Area .......................................................................................................................... 21 CONTEXT ...................................................................................................................................... -

DEA Overview

1.12.2015 DEA Overview Heather McKee and Catherine O’Connor Community Planning Partnership Board Strategic framework with high level outcomes Underpinned by evidence Underpinned evidence by base Thematic Operational level within which sits existing partnerships or aligned partnerships Supported Economic Supported Joint Health & Environment Safety and Good Development & Strategic Officer (and Spatial) Regeneration Wellbeing Relations (PCSP) Stakeholder Working Forum Group Programme of Engagement and Communications Local Level District Electoral Area (DEA) Fora Slieve Gullion Forum, Newry Forum, Crotlieve Forum, Mournes Forum, Slieve Croob Forum, Downpatrick Forum, Rowallane Forum DEMOGRAPHICS The 2015 population estimate for Newry, Mourne and Down District Council Area is 175,974. The estimated population for each DEA is as follows: - Slieve Gullion 26,388 - Newry 28,456 - Crotlieve 25,554 - The Mournes 30,843 - Slieve Croob 20,373 - Downpatrick 22,291 - Rowallane 22,069 AGE PROFILE There are an estimated 39,717 persons aged 0-15 residing within the Newry, Mourne and Down District Council Area accounting for 22.6% of the total which is above the NI average. There are an estimated 24,726 persons aged 65+ within the Newry, Mourne and Down area accounting for 14% of the population. The working age population (16-64 years) in Newry, Mourne and Down is estimated to be 111,537 in 2015. However it should be noted that the 40-64 age group has grown far more than the 16-39 age group since 2001. PLAY PARKS Newry, Mourne and Down has numerous play parks spread across the District and has also begun to undertake a new Play Park Strategy for the new super council. -

Visitors Is Tours, Taking You on a Journey Lough and Offers Magnificent Views

Kilkeel Harbour Dromore High Cross Ring of Gullion Mourne Mountains Newry Silent Valley Reservoir 3 Day Great Outdoors thrown from the Cooley Mountains, high street selection at The Quays Parks, Gardens and Nature Reserve on the other side of Carlingford Lough, or Buttercrane Centres in Newry, or by the giant Fionn mac Cumhaill. Newry’s Hill Street and Monaghan Day 1: Ballymoyer Don’t miss the brand new Mountain Street where you will find men’s 5 Day Visit political and cultural history of the stop for breakfast, then south towards coast route east, on to the village take the opportunity to spend the Visit picturesque Ballymoyer, outside Bike Trails in Rostrevor’s Kilbroney Park. designer shops, ladies fashion Make your day Spas, Mountains, Gardens region from prehistoric flints and Camlough Lake, abundant with birdlife of Rostrevor situated at the foot of morning chilling out with a seaweed the village of Whitecross. Ballymoyer boutiques, and independent retailers. Bagenal’s Castle, Newry in the Mournes and Historic Towns medieval sculpture to 20th century and rare aquatic wildlife. Continue Rostrevor Forest with its 250 year old bath and spa treatment in Soak House was constructed in 1778, Day 3: Castlewellan Hill Street is also home to the Thursday ceramics and glassware. In the south to tranquil Killeavy and on to oak trees and brand new world class Seaweed Baths located along the and the demesne grounds are now Visit Castlewellan Forest Park and and Saturday variety markets. Don’t 3 Day Family Break stopping off at either Castlewellan Tailor-made to inspire, Day 1: Banbridge afternoon, explore this fascinating Slieve Gullion Forest Adventure Park Mountain Bike Trails. -

Mourne AONB Leaflet

Steve Murphy Steve and Wilson Ernie , Thompson David - Trust National , Johnston Marty Photograph y www.mournelive.com e-mail. [email protected] e-mail. T el. (028) 43 (028) el. 7 2 4059 F 4059 2 ax. (028) 43 (028) ax. 72 6493 72 Co. Down BT34 OHH BT34 Down Co. NEWCASTLE 87 Central Promenade Central 87 Mourne Heritage Trust Heritage Mourne 1:25,000 OSNI Slieve Croob Slieve OSNI 1:25,000 1:25,000 OSNI The Mournes The OSNI 1:25,000 1:50,000 OSNI Sheet 29 The Mournes The 29 Sheet OSNI 1:50,000 Maps Castlewellan Forest Park Forest Castlewellan Castlewellan Arboretum, Tollymore Forest Park, Forest Tollymore Arboretum, Castlewellan - Service Forest including natural history, built heritage and tourism and heritage built history, natural including Fact sheets on a variety of topics of variety a on sheets Fact - Trust Heritage Mourne W at The Silent Valley Silent The - Service er Leaflets Annalong and Ne and Annalong wcastle. Carlingford Lough. Carlingford name: at Silent Valley (445m) and east of Hare’s Gap (586m). Gap Hare’s of east and (445m) Valley Silent at name: www.downdc.gov.uk - Council District Down fishing harbour in Kilkeel and smaller commercial harbours at harbours commercial smaller and Kilkeel in harbour fishing such as those at Dundrum Bay, Mill Bay and the fjord inlet of inlet fjord the and Bay Mill Bay, Dundrum at those as such Ne www.newryandmourne.gov.uk - Council District Mourne and wry Mountain of the r the of Mountain Slie ocks. Two mountains carry this carry mountains Two ocks. -

Planning Applications

Planning applications Full details of the following planning applications including plans, maps and drawings are available to view on the NI Planning Portal www.planningni.gov.uk or by contacting (028) 9182 4006 between 9am and 3pm. However, during the Covid-19 pandemic we cannot accommodate any call-ins to the Council Planning Office. Whenever possible, written comments should be submitted within the next 14 days. We request comments as early as possible, but we must take account of any representations that raise material planning considerations received before the application is actually determined. Please quote the application number in any correspondence and note that all representations made, including objections, will be posted on the NI Planning Portal. Please refer to the Council’s guidance on how to comment on a planning application which is available on the Council’s website www.ardsandnorthdown.gov.uk/planning-applications. Information regarding the schedule for the Planning Committee to be held on 3rd November 2020 will be published on the Council’s website under ‘Next Planning Committee’ on 21st October. Initial Advertisements Application No. Location Proposal LA06/2020/0565/F 20m N.E. of 16 Loughdoo Detached dwelling. Road, Ardkeen, Kircubbin LA06/2020/0786/F 25 Manse Road, Cloughey Single storey side extension incorporating a kitchen, laundry room and bin store. LA06/2020/0850/F 73 Moss Road, Millisle Two-storey rear extension to dwelling LA06/2020/0856/F 136 Moss Road, Millisle Farm worker’s dwelling - Removal of occupancy