An Evaluation of the Educational Impact of the Sisimpur Community Outreach Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sesame Street Combining Education and Entertainment to Bring Early Childhood Education to Children Around the World

SESAME STREET COMBINING EDUCATION AND ENTERTAINMENT TO BRING EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION TO CHILDREN AROUND THE WORLD Christina Kwauk, Daniela Petrova, and Jenny Perlman Robinson SESAME STREET COMBINING EDUCATION AND ENTERTAINMENT TO Sincere gratitude and appreciation to Priyanka Varma, research assistant, who has been instrumental BRING EARLY CHILDHOOD in the production of the Sesame Street case study. EDUCATION TO CHILDREN We are also thankful to a wide-range of colleagues who generously shared their knowledge and AROUND THE WORLD feedback on the Sesame Street case study, including: Sashwati Banerjee, Jorge Baxter, Ellen Buchwalter, Charlotte Cole, Nada Elattar, June Lee, Shari Rosenfeld, Stephen Sobhani, Anita Stewart, and Rosemarie Truglio. Lastly, we would like to extend a special thank you to the following: our copy-editor, Alfred Imhoff, our designer, blossoming.it, and our colleagues, Kathryn Norris and Jennifer Tyre. The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s) and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars. Support for this publication and research effort was generously provided by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and The MasterCard Foundation. The authors also wish to acknowledge the broader programmatic support of the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, the LEGO Foundation, and the Government of Norway. Brookings recognizes that the value it provides is in its absolute commitment to quality, independence, and impact. -

The Educational and Cultural Impact of Sisimpur

PROGRAMME RESEARCH 20/2007/E 51 June H. Lee The educational and cultural impact of Sisimpur Bangladesh’s Sesame Street Since 2005, the Bangladeshi Sesa- me Street.1 In Bangladesh, the me Street is broadcast on national groundwork for Sisimpur began in TV, and specially equipped rick- 2003 when a team from Sesame shaws bring the programme into Workshop visited Bangladesh to as- remote villages. Sisimpur has its sess the feasibility of an educational own special Muppet characters, TV programme for preschoolers. and the programme is found to fos- While Bangladesh has made signifi- ter basic literacy and mathematical cant strides in expanding primary skills as well as the notion of educa- school enrolment in the past decade tion being a joyful experience. (Lusk/Hashemi/Haq, 2004), govern- ment provisions for early childhood education programmes have re- “They teach you what ‘a’ is for, what ‘b’ mained limited. At the same time, te- sic literacy and math skills, health, hy- is for. I learn them. When they ask what levision is a popular medium with giene, nutrition, respect, understand- ‘jha’ is for, Tuktuki flies away in a ‘jhor’ growing reach among the population; ing, diversity, family and community (storm) and then comes down on earth it is also an important avenue for relations, and art and culture. Each again.” disseminating information (such as piece of content produced for Sisim- Ratul, Mirka village, Bhaluka, Bangla- pur addresses a specific educational desh (Kibria, 2006) on health; Associates for Communi- ty and Population Research, 2002). objective. atul, a boy from a village in Using television to deliver educational Sisimpur launched in April 2005 on Bhaluka in Bangladesh, is content promised to be a cost-effecti- Bangladesh Television, the country’s Rspeaking about Sisimpur, the ve way to provide informal early only national television channel.2 The Bangladeshi co-production of Sesa- childhood opportunities to children show is set in a village that centres throughout Bangladesh. -

Bringing Hope and Opportunity to Children

Bringing Hope and Opportunity to Children Affected by Conflict and Crisis Around the World Sesame Workshop and partners are leading the largest coordinated early childhood intervention in the history of humanitarian response. The scale of the global refugee crisis is staggering. Today, more than 70 million people are displaced worldwide — and half are children. The most formative years of their lives have been marked by upheaval, chaos, and violence, all with lasting effects on their development and wellbeing. Millions of young children are spending their childhoods without early childhood development (ECD) opportunities that can help them recover from adverse experiences and prepare them to thrive. In the face of this urgent humanitarian crisis, Sesame Workshop and the International Rescue Committee (IRC), with support from the MacArthur Foundation, partnered to create Ahlan Simsim (“Welcome Sesame” in Arabic), a program that delivers early learning and nurturing care to children and caregivers affected by conflict and displacement in Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria. Building on our ambitious efforts in the Syrian response region, Sesame Workshop has teamed up with the LEGO Foundation, BRAC, and the IRC to support hundreds of thousands of children and caregivers affected by both the Syrian crisis in Jordan and Lebanon and the Rohingya refugee crisis in Bangladesh, by ensuring access to play-based learning opportunities that are vital to their development. Together with other stakeholders, we have the potential to transform humanitarian response, benefitting children affected by conflict and crisis around the world. Ahlan Simsim: Delivering vital early learning to children in the Syrian response region The ongoing conflict in Syria has Mass Media Direct Services displaced over 12 million people. -

Big Dreams Sparked by a Spirited Girl Muppet

GLOBAL GIRLS’ EDUCATION Big Dreams Sparked by a Spirited Girl Muppet Globally, an estimated 510 million women grow up unable to read and write – nearly twice the rate of adult illiteracy as men.1 To counter this disparity in countries around the world, there’s Sesame Street. Local adaptations of Sesame Street are opening minds and doors for eager young learners, encouraging girls to dream big and gain the skills they need to succeed in school and life. We know these educational efforts yield benefits far beyond girls’ prospects. They produce a ripple effect that advances entire families and communities. Increased economic productivity, reduced poverty, and lowered infant mortality rates are just a few of the powerful outcomes of educating girls. “ Maybe I’ll be a police officer… maybe a journalist… maybe an astronaut!” Our approach is at work in India, Bangladesh, Nigeria, Egypt, South Africa, Afghanistan, and many other developing countries where educational and professional opportunities for women are limited. — Khokha Afghanistan BAGHCH-E-SIMSIM Bangladesh SISIMPUR Brazil VILA SÉSAMO China BIG BIRD LOOKS AT THE WORLD Colombia PLAZA SÉSAMO Egypt ALAM SIMSIM India GALLI GALLI SIM SIM United States Indonesia JALAN SESAMA Israel RECHOV SUMSUM Mexico PLAZA SÉSAMO Nigeria SESAME SQUARE Northern Ireland SESAME TREE West Bank / Gaza SHARA’A SIMSIM South Africa TAKALANI SESAME Tanzania KILIMANI SESAME GLOBAL GIRLS’ EDUCATION loves about school: having lunch with friends, Watched by millions of children across the Our Approach playing sports, and, of course, learning new country, Baghch-e-Simsim shows real-life girls things every day. in situations that have the power to change Around the world, local versions of Sesame gender attitudes. -

Sesame Workshop Bangladesh

Sesame Workshop Bangladesh REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL (RFP) Title of the Consultancy Hiring an agency for conducting a formative research on Sisimpur new storybook Project USAID’s Early Childhood Development Mass Media Activity, Sisimpur Release Date: December 17, 2019 Agency briefing session: December 23, 2019 at 3:30 PM Submission Deadline: January 5, 2020 by 11:59 PM 1 1 ABOUT SESAME WORKSHOP BANGLADESH Sesame Workshop Bangladesh (SWB), the country office of Sesame Workshop, produces Sisimpur, the local version of world-famous kids’ television program Sesame Street in Bangladesh. Sisimpur has been made possible in Bangladesh with the generous support from USAID. The TV show has been airing since 2005 with a view to making early childhood education delightful and enjoyable for Bangladeshi kids. This program has been developed to address educational needs of kids between the ages of 3 and 8. Along with the kids, parents, care givers and teachers are involved in Sisimpur through different school and community- based intervention. SWB undertakes different school and community-based intervention to reinforce the messages aired through TV program. It develops and distributes school based educational materials, train teachers, monitors classroom activities and provides technical assistance for using them in the classroom along with community engagement and outreach programs. Since its inception, Sisimpur has been a tremendous success in Bangladesh and within a very short time, it became the most famous television program for kids as well as their caregivers. Further information can be found at www.Sisimpur.org.bd and www.sesameworkshop.org/ 2 ABOUT THE RFP Sesame Workshop Bangladesh started the production brand new 20 storybooks for pre- primary to grade three children in Bangladesh. -

Sesamstraat Als Opvoeder

Sesamstraat als opvoeder Een narratieve analyse van het programma Sesamstraat , in het licht van de sociaal-educatieve doelstellingen. Mirjam Hut, 3279197 16 juni, 2010 Aantal woorden: 5455 Bachelor Eindscriptie CIW (Media en educatie) Begeleider: Eef Masson Sesamstraat als opvoeder - Eindscriptie Media en Educatie - Mirjam Hut, 3279197 1 __________________________________________________________________________________________ Inhoud 1. Inleiding 2 2. Doelstellingen Sesamstraat 6 3. Aanpak 8 3.1 Analyse methode 8 3.2 Relevante leertheorieën 9 4. Analyse 10 4.1 Opbouw van het programma 10 4.2 Structuur van de items 12 4.3 Personages 13 5. Conclusie 16 Bronnen Bijlagen I. Transcript, Sesamstraat aflevering 'Ziek', 18 januari 2010 II. Transcript, Sesamstraat aflevering 'Boerderij', 11 november 2009 III. Transcript, Sesamstraat aflevering 'Post', 17 januari 2010 Sesamstraat als opvoeder - Eindscriptie Media en Educatie - Mirjam Hut, 3279197 2 __________________________________________________________________________________________ 1. Inleiding In 1967 publiceerde Joan Ganz Cooney in "The Potential Uses of Television in Preschool Education" haar aanbevelingen over voorschoolse educatieve televisie voor kinderen. 1 Hiermee zette zij de eerste stap in de ontwikkeling van een kinderprogramma dat dertig jaar later wereldwijd op de televisie uitgezonden zou worden, Sesame Street . Cooney voerde haar onderzoek uit in opdracht van experimenteel psycholoog Lloyd Morrisett. In de tijd van de publicatie van Cooney’s rapport gingen de meeste Amerikaanse kinderen uit de getto's niet naar de kleuterschool. Zij begonnen daardoor op de basisschool al met een leerachterstand, die zij gedurende hun schooltijd nooit meer helemaal zouden kunnen wegwerken. 2 Morrisett wilde kinderen uit achterstandswijken die niet naar de kleuterschool gingen, voorbereiden op de basisschool door voorschoolse educatie aan te bieden. -

Preliminary Program Schedule

Preliminary Program Schedule 102nd ASA Annual Meeting August 11-14, 2007 New York, New York Locations: The facility in which each program session and meeting activity is being held is shown with each listing. The specific room location of program/meeting activities is available only in the Final Program, which is distributed on-site in New York to meeting registrants. Program Corrections: The information printed here reflects session updates received from organizers through June 11, 2007. Corrections for the Final Program were due by June 15, 2007. Changes received too late for the Final Program will appear in the Program Changes section of the Convention Bulletin which is distributed to meeting registrants on-site. File Updates: Please note that this pdf file will NOT be updated; it is a snapshot of the program schedule at one point in time. For up to date information, search the online Preliminary Program database accessible via the ASA website. Warning: This version of the program schedule does not reflect presenters being dropped from sessions because they have (1) not preregistered, or (2) exceeded the number of listings permitted by the program policies. 1 Friday, August 10 nd Opening of the 102 Annual Conferences Meeting Chairs Conference (8:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m.; ticket required for admission) — Hilton New York 7:00 p.m. Plenary Directors of Graduate Study Conference (12:30 – 5:00 p.m.; ticket required for admission) — Hilton New York 2. Plenary Session. Democratic Transition: The Example of Chile Courses Hilton New York 1. Pre-convention Course. Funding Sources for Social Session Organizers: Susan Eckstein, Boston Science Research University; and Frances Fox Piven, City University Hilton New York of New York Ticket required for admission Presider: Frances Fox Piven, City University of New Leaders: Mercedes Rubio, National Inst of Mental Health York Christine O'Brien, National Academies Fellowships Introduction. -

The Loudest Roar

’06 SESAME WORKSHOP 2006 ANNUAL REPORT SESAME WORKSHOP 2006 ANNUAL REPORT THE LOUDEST ROAR [ The potential for Sesame Street in India to make a positive change is enormous: 128 million children between the ages of 2 and 6 live in India and two-thirds lack access to early childhood care and education. ] DEPLOYING ELMO: UPSIDE DOWN: HELP FOR FAMILIES ABSTRACT THINKING DURING MILITARY GOES TO THE GYM DEPLOYMENT NEW ACTIVITIES IN WORD ON THE STREET: THE MIDDLE EAST NEW DIRECTIONS IN LITERACY LEARNING Galli Galli Sim Sim Mobile Community Viewing event, Dakshinpuri, Delhi President’s Letter Chamki INDIA Whether the “loudest roar” emanates from Boombah, the friendly lion of our newest Sesame Street coproduction in India, or one of the many other characters in Sesame Workshop’s global family, the message is the same: Educate a child; change the world. Sesame Workshop 2006 Annual Report 03 President’s Letter Educate a child, change the world — We’re talking ment reaches far beyond its own television audiences, about social change through Muppets, through songs and Miditech Pvt. Ltd., a gifted local production and stories children love and parents trust. We’re company,to launch Galli Galli Sim Sim on television joined around the world in this effort by unlikely (public, cable, and satellite) and through educational coalitions of government ministers, corporate leaders, outreach. This simultaneous launch was a first for us and social activists. Why? Because we all hope for a internationally and a strong testament to a shared better future, and that future begins with children. vision of reaching children in need. -

Nigerian Educators' Appropriation of Sesame Classroom Materials

Global early childhood policies 17 Localizing Play-Based Pedagogy: Nigerian Educators’ Appropriation of Sesame Classroom Materials Naomi A. Moland School of International Service, American University Abstract This article examines how international organizations promote play-based pedagogical approaches in early childhood settings around the world, and how local educators respond. As a case study, I investigated Sesame Workshop’s efforts to introduce play-based approaches in Nigerian classrooms. In addition to producing a Nigerian version of Sesame Street (called Sesame Square), Sesame Workshop trains educators in play-based approaches and has distributed alphabet flashcards, puppet kits, and storytelling games to more than 2,700 early childhood classrooms across Nigeria. These materials were intended to support Sesame Square’s messages, and to foster interactive, child-centered learning experiences. However, teachers often used the materials in ways that reflected more rote-based, teacher- centered approaches. Data was gathered through observations and interviews in 27 educational sites across Nigeria that use Sesame materials. Findings reveal that teachers’ resistance to play-based approaches was sometimes for structural reasons (e.g., large class sizes), and sometimes related to their knowledge and training (e.g., they were accustomed to drilling the alphabet). I argue that ideals about constructivist, play-based learning are being disseminated by international organizations—alongside contrasting formalistic pedagogical approaches—and that all approaches will shift as they are localized. I question if approaches that are considered universally developmentally appropriate are relevant in all settings, and explore how early childhood educators adapt global pedagogical trends to make sense in their classrooms. I call for international organizations to explore context-appropriate play-based approaches that develop educators’ capacities to help all children thrive, while also incorporating local cultural beliefs about childhood and teaching. -

Swchildstories Spread

ANNUAL REPORT 2007 WORKSHOP SESAME SESAME WORKSHOP 2007 ANNUAL REPORT ORG . SESAMEWORKSHOP . WWW 10023 – 212.595.3456 – YORK NEW , YORK NEW – PLAZA LINCOLN ONE What began as an American phenomenon in the late ’60s is still going strong in the U.S., as well as in Egypt, India, South Africa, Kosovo and more than 120 other countries around the world. The Sesame Workshop story is a CHILDREN’ S STORY, played out millions of times a day the world over. A MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT A MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT Dear Friend, stories with us. Families like Ntlabi’s and Tamryn’s in the Limpopo and Free State provinces of South At the Workshop, we tell stories to help children Africa, where the Sesame Street coproduction, Takalani learn – learn about faraway places, about how to Sesame, is reducing the fear and stigma associated treat one another with empathy and respect, about with HIV/AIDS. Families like the Lopezes:Army Staff how to stay healthy and strong, and of course, about Sergeant Ernesto Lopez is in Iraq on his third tour letters and numbers. of duty and our Sesame Street outreach initiative is This book is a new collection of stories – not the ones helping his and other families cope with the challenges we tell, but the ones children tell us. of military deployment. We spoke with Aman who lives in a slum on the outskirts of Delhi, who finds joy This collection is about the ways in which our work and learning in the Indian version of Sesame Street, affects the life chances, experiences and opportunities – Galli Galli Sim Sim. -

Winter 2005 Volume 76, Number 2

BOWDOINWinter 2005 Volume 76, Number 2 The Mind of a Goalie winter2005 contents The View From the Crease 18 By Mel Allen Photographs by Bob Handelman Sports fans agree — there’s something different about goalies, some way of looking at the game, or even the world, that only they have. Mel Allen takes an in-depth look at how men’s ice hockey goalie George Papachristopolous ’06 handles the pressure, and we talk to other Bowdoin goalies about their rituals, pre-game routines, and other tricks of the goalie trade. Joining in the Dance 28 By Selby Frame Photographs by James Marshall In the years since she arrived on campus to help Bowdoin begin a dance program in the early days of co-education, Professor of Dance June Vail has built one of the most inclusive, welcoming, and vibrant dance programs around. Climate Change in the Arctic: Is Bowdoin’s Mascot Headed for a Meltdown? 32 By Douglas McInnis Illustrations by John Bowdren The polar bear population in the Arctic has changed little in the nearly 87 years since Donald MacMillan sent Bowdoin the bear that stands guard in Morrell Gym, but some say the polar bear could actually become extinct in this century, a victim of global warming. Departments Mailbox 2 Bookshelf 4 College & Maine 6 Weddings 38 Class News 44 Obituaries 79 BOWDOINeditor’s note staff It’s winter in Maine, and January simply will not end. Money is short, patience is Volume 76, Number 2 thin, and the line at the coffeeshop is always long. Looking beyond Brunswick, Winter, 2005 one’s mood might plummet further – those who have friends and loved ones in MAGAZINE STAFF Iraq must know little but worry, and the figures of death and destruction from December’s tsunami loom as large as the wave itself. -

Sesame Workshop Annual Report.Pdf

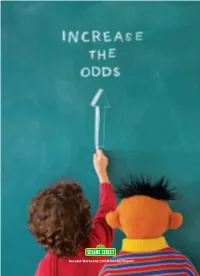

Sesame Workshop 2008 Annual Report If children experience the joy of learning, it’s more likely they’ll be lifelong learners. If they learn healthy habits, it’s more likely they’ll grow up healthy and strong. If they gain a sense of themselves and an appreciation of others, it’s more likely they’ll engage others with respect and understanding. It’s that simple and that complicated. Sesame Workshop is using the power of media – and the power of Muppets – to increase the odds that all children reach their highest potential, and in so doing, make a better world for us all. Disadvantaged children in the United States learn 15,000 fewer words by the time they reach first grade than their more advantaged peers.1 In the United States alone, Sesame Street provides the building blocks of literacy for an estimated 12 million children each week.2 1) L. Moats, Overcoming the Language Gap. American Educator, September 5-9, 2001. 2) Sesame Workshop, The Media Utilization Study, 2007. Sesame Workshop, Sesame Street Brand Tracking, 2008. Sesame Workshop is increasing the odds that children are ready to read and write, and, as a result, are ready for success in school and life. More than 60 percent of families with MAkIng ReAdIng Cool incomes of $25,000 or less report their children age 5 or younger view In January 2009, Sesame Sesame Street at least once a week.1 Workshop launched The Electric Company, a fresh take on the 1970s series of the same name. The all-new Closing the series, on television, online, and through community WoRd Gap outreach, brings literacy to life for struggling readers Sesame Street’s thirty- ages 6 to 9, especially those ninth season focuses from low-income families.