The Use of Prior Restraints on Publication in the Age of Wikileaks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Government Hacking What Is It and When Should It Be Used?

Government Hacking What is it and when should it be used? Encryption is a critical component of our day-to-day lives. For much of the world, basic aspects of life rely on encryption to function. Power systems, transport, financial markets, and baby monitors1 are more trustworthy because of encryption. Encryption protects our most vulnerable data from criminals and terrorists, but it can also hide criminal content from governments. Government hacking is one of the approaches national security and law enforcement agencies use to obtain access to otherwise encrypted information (e.g. the FBI hired a hacking company to unlock the iPhone at the center of the San Bernardino case2). It complements their other efforts to obtain exceptional access3 by asking or requiring tech companies to have the technical ability to decrypt users’ content when it is needed for law enforcement purposes. The Internet Society believes strong encryption is vital to the health of the Internet and is deeply concerned about any policy or action that might put that in jeopardy — regardless of its motivation. Government hacking poses a risk of collateral damage to both the Internet and its users, and as such should only ever be considered as a tool of last resort. Government hacking defined We define ‘government hacking’ as government entities (e.g. national security or law enforcement agencies or private actors on their behalf) exploiting vulnerabilities in systems, software, or hardware to gain access to information that is otherwise encrypted, or inaccessible. Dangers of government hacking Exploiting vulnerabilities of any kind, whether for law enforcement purposes, security testing, or any other purpose, should not be taken lightly. -

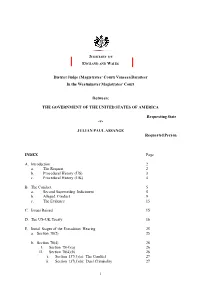

USA -V- Julian Assange Judgment

JUDICIARY OF ENGLAND AND WALES District Judge (Magistrates’ Court) Vanessa Baraitser In the Westminster Magistrates’ Court Between: THE GOVERNMENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Requesting State -v- JULIAN PAUL ASSANGE Requested Person INDEX Page A. Introduction 2 a. The Request 2 b. Procedural History (US) 3 c. Procedural History (UK) 4 B. The Conduct 5 a. Second Superseding Indictment 5 b. Alleged Conduct 9 c. The Evidence 15 C. Issues Raised 15 D. The US-UK Treaty 16 E. Initial Stages of the Extradition Hearing 25 a. Section 78(2) 25 b. Section 78(4) 26 I. Section 78(4)(a) 26 II. Section 78(4)(b) 26 i. Section 137(3)(a): The Conduct 27 ii. Section 137(3)(b): Dual Criminality 27 1 The first strand (count 2) 33 The second strand (counts 3-14,1,18) and Article 10 34 The third strand (counts 15-17, 1) and Article 10 43 The right to truth/ Necessity 50 iii. Section 137(3)(c): maximum sentence requirement 53 F. Bars to Extradition 53 a. Section 81 (Extraneous Considerations) 53 I. Section 81(a) 55 II. Section 81(b) 69 b. Section 82 (Passage of Time) 71 G. Human Rights 76 a. Article 6 84 b. Article 7 82 c. Article 10 88 H. Health – Section 91 92 a. Prison Conditions 93 I. Pre-Trial 93 II. Post-Trial 98 b. Psychiatric Evidence 101 I. The defence medical evidence 101 II. The US medical evidence 105 III. Findings on the medical evidence 108 c. The Turner Criteria 111 I. -

PEER-REVIEW FEEDBACK on the GOODNESS FIELD: a Guidebook for Proactive Nonviolence

PEER-REVIEW FEEDBACK ON THE GOODNESS FIELD: A Guidebook for Proactive Nonviolence Bob Aldridge's powerful book, The Goodness Field: A Guidebook for Proactive Nonviolence points out the need and opportunity for a Global Satyagraha Movement – nonviolent, active, creative, and compassionate – to challenge the US addiction to power and greed which feeds our nation's endless wars and empire. Aldridge gives some very helpful suggestions for how to build that movement. This is not a pipe dream. We, the world's people can make it happen! – David Hartsough Author, Waging Peace: Global Adventures of a Lifelong Activist Co-Founder, Nonviolent Peaceforce and World beyond War - - - - I am in wholehearted agreement with Bob Aldridge's call for a "Global Satyagraha Movement inspired by a Global Constructive Pro- gram.” I'm glad to say, also, that these very ideas are catching on. If humanity is to rescue itself from the materialism, the low human image based on outdated science, and the devastation that they are causing to our personal and social lives -- indeed for our continued existence -- I can see no other way of doing that than the discovery of what he calls the "goodness field" that science is beginning to discover and traditional wisdom has long spoken of, by whatever name. – Michael N. Nagler President, Metta Center for Nonviolence Author, The Third Harmony: Nonviolence and the New Story of Human Nature - - - - Every so often an elder, whose life has embodied the way of faith, peace and justice, writes a “testament” (as Jim Douglass rightly calls this book), one that peers well past what the rest of us see. -

The Theory of Prosecution You Love for Julian Assange May Look Different When Applied to Jason Leopold

THE THEORY OF PROSECUTION YOU LOVE FOR JULIAN ASSANGE MAY LOOK DIFFERENT WHEN APPLIED TO JASON LEOPOLD The WaPo confirmed something Seamus Hughes disclosed last night: Sometime before August 22, EDVA had filed a sealed complaint (not indictment) against Julian Assange. WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange has been charged under seal, prosecutors inadvertently revealed in a recently unsealed court filing — a development that could significantly advance the probe into Russian interference in the 2016 election and have major implications for those who publish government secrets. The disclosure came in a filing in a case unrelated to Assange. Assistant U.S. Attorney Kellen S. Dwyer, urging a judge to keep the matter sealed, wrote that “due to the sophistication of the defendant and the publicity surrounding the case, no other procedure is likely to keep confidential the fact that Assange has been charged.” Later, Dwyer wrote the charges would “need to remain sealed until Assange is arrested.” Dwyer is also assigned to the WikiLeaks case. People familiar with the matter said what Dwyer was disclosing was true, but unintentional. The confirmation closely follows a WSJ story describing increased confidence that the US will succeed in extraditing Assange for trial. The confirmation that Assange has been charged has set off a frenzy, both among Assange supporters who claim this proves their years of claims he was indicted back in 2011 and insisting that charging him now would amount to criminalizing journalism, and among so-called liberals attacking Assange lawyer Barry Pollack’s scolding of DOJ for breaking their own rules. I’ve long been on record saying that I think most older theories of charging Assange would be very dangerous for journalism. -

Julian Assange Judgment

JUDICIARY OF ENGLAND AND WALES District Judge (Magistrates’ Court) Vanessa Baraitser In the Westminster Magistrates’ Court Between: THE GOVERNMENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Requesting State -v- JULIAN PAUL ASSANGE Requested Person INDEX Page A. Introduction 2 a. The Request 2 b. Procedural History (US) 3 c. Procedural History (UK) 4 B. The Conduct 5 a. Second Superseding Indictment 5 b. Alleged Conduct 9 c. The Evidence 15 C. Issues Raised 15 D. The US-UK Treaty 16 E. Initial Stages of the Extradition Hearing 25 a. Section 78(2) 25 b. Section 78(4) 26 I. Section 78(4)(a) 26 II. Section 78(4)(b) 26 i. Section 137(3)(a): The Conduct 27 ii. Section 137(3)(b): Dual Criminality 27 1 The first strand (count 2) 33 The second strand (counts 3-14,1,18) and Article 10 34 The third strand (counts 15-17, 1) and Article 10 43 The right to truth/ Necessity 50 iii. Section 137(3)(c): maximum sentence requirement 53 F. Bars to Extradition 53 a. Section 81 (Extraneous Considerations) 53 I. Section 81(a) 55 II. Section 81(b) 69 b. Section 82 (Passage of Time) 71 G. Human Rights 76 a. Article 6 84 b. Article 7 82 c. Article 10 88 H. Health – Section 91 92 a. Prison Conditions 93 I. Pre-Trial 93 II. Post-Trial 98 b. Psychiatric Evidence 101 I. The defence medical evidence 101 II. The US medical evidence 105 III. Findings on the medical evidence 108 c. The Turner Criteria 111 I. -

America Exposed Who’S Watching You Through Your Computer’S

America Exposed Who’s Watching You Through Your Computer’s Camera? May 2017 By: James Scott, Senior Fellow, The Institute for Critical Infrastructure Technology 1 America Exposed Who’s Watching You Through Your Computer’s Camera May 2017 Authored by: James Scott, Sr. Fellow, ICIT Except for (1) brief quotations used in media coverage of this publication, (2) links to the www.icitech.org website, and (3) certain other noncommercial uses permitted as fair use under United States copyright law, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher. For permission requests, contact the Institute for Critical Infrastructure Technology. Copyright © 2017 Institute for Critical Infrastructure Technology – All Rights Reserved ` 2 Support ICIT & Increase Webcam Privacy CamPatch®, the world’s leading manufacturer of webcam covers, is proud to donate 100% of net proceeds to ICIT. Custom Branded Webcam Covers are a powerful tool for security training initiatives, and are a valuable and impactful promotional giveaway item. Visit www.CamPatch.com or contact [email protected] to learn more. Upcoming Events The Annual ICIT Forum June 7, 2017, The Four Seasons Washington D.C. www.icitforum.org ` 3 Contents Are You Being Watched? .............................................................................................................................. 4 Computing Devices -

Cia-Wikileaks-Task-Force.Pdf

TOP SECRET//HCS-O-P/SI//ORCON/NOFORN/FISA 17 October 2017 WikiLeaks Task Force Final Report TOP SECRET//HCS-O-P/SI//ORCON/NOFORN/FISA 17 October 2017 Memo To: Director, Central Intelligence Agency Deputy Director, Central Intelligence Agency Chief Operating Officer, Central Intelligence Agency From: WikiLeaks Task Force, Subject: WikiLeaks Task Force Final Report Executive Summary WikiLeaks’ announcement on 7 March that it possessed cyber tools from CIA’s Center for Cyber Intelligence (CCI), dubbed “Vault 7,” marked the largest data loss in CIA history. In its initial public disclosure, WikiLeaks provided the names and brief descriptions of multiple tools that CIA developed for cyber operations. Since 7 March, WikiLeaks has published more comprehensive descriptions of 35 tools, including internal CIA documents associated with each tool. — We assess that in spring 2016 a CIA employee stole at least 180 gigabytes to as much as 34 terabytes of information. This is roughly equivalent to 11.6 million to 2.2 billion pages in Microsoft Word. This data loss includes cyber tools that resided on the Center for Cyber Intelligence (CCI) software development network (DevLAN). We cannot determine the precise scope of the loss because, like other mission systemsa at that time, DevLAN did not require user activity monitoring or other safeguards that exist on our enterprise system. — — To date, WikiLeaks has released user and training guides and limited source code from two parts of DevLAN: Stash, a source code repository, and Confluence, a collaboration and communication platform. All of the documents reveal, to varying degrees, CIA’s tradecraft in cyber operations. -

Going Dark: Impact to Intelligence and Law Enforcement and Threat Mitigation

GOING DARK: IMPACT TO INTELLIGENCE AND LAW ENFORCEMENT AND THREAT MITIGATION Bonnie Mitchell Krystle Kaul G. S. McNamara Michelle Tucker Jacqueline Hicks Colin Bliss Rhonda Ober Danell Castro Amber Wells Catalina Reguerin Cindy Green-Ortiz Ken Stavinoha ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to first thank the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) for its generous funding and support for our study and learning journey to the DEFCON hacking conference. We are also very grateful to the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) for its support during the duration of the program. We could not have completed this study without the unwavering support and dedication of Ms. Bonnie Mitchell, ODNI Deputy National Intelligence Manager for the Western Hemisphere and the Homeland, our devoted Team Champion who steered us throughout this study and helped turn an idea into a product. We would like to acknowledge and thank each member of our public-private sector working group for their tireless efforts from around the U.S., which includes Krystle Kaul, G. S. McNamara, Michelle Tucker, Jacqueline Hicks, Colin Bliss, Rhonda Ober, Danell Castro, Amber Wells, Catalina Reguerin, Cindy Green- Ortiz and Ken Stavinoha. We are very thankful for all the unique insight we received from interviewees who contributed to this report by educating our group on the many aspects of ‘going dark,’ and we take full responsibility for any and all errors of fact or interpretation implied or explicit in this paper. Our interviewees include the Village sponsors at DEF CON, private sector industry experts and government officials. We are thankful for the interesting and diverse perspectives particularly from senior government officials and private sector experts. -

NH-ISAC Daily Security Intelligence Report – April 11, 2017

NH-ISAC Daily Security Intelligence Report – April 11, 2017 This information is marked TLP GREEN: This information is marked TLP GREEN: Recipients may share TLP:GREEN information with peers and partner organizations within their sector or community, but not via publicly accessible channels. Information in this category can be circulated widely within a particular community. TLP:GREEN information may not be released outside of the community. BREACH REPORT Tullamore Hospital Patient's Information Sent to Wrong Person After Data Blunder A data breach at Tullamore Hospital is among 212 cases revealed today, the Irish Independent have reported. 212 data protection breaches, where patient's private information was misused or mishandled, were recorded by the HSE last year, including a major blunder in Tullamore. In the Offaly hospital's case, the office of the Data Protection Commissioner actually received information pertaining to a patient when those private details were faxed in error… Link – http://www.offalyexpress.ie/news/home/244553/tullamore-hospital-patient-s- information-sent-to-wrong-person-after-data-blunder.html CRIME and INCIDENT REPORT Microsoft Office Zero-Day Used to Push Dridex Banking Trojan The operators of the Dridex botnet are using the recently disclosed Microsoft Office zero- day to spread a version of their malware, the infamous Dridex banking trojan. It is unclear at this time if the Dridex gang was the group that discovered the zero-day, or if they just figured out a way to exploit it after McAfee and FireEye disclosed public details over the weekend… Link – https://www.bleepingcomputer.com/news/security/microsoft-office-zero-day- used-to-push-dridex-banking-trojan/ Dridex Campaigns Hitting Millions of Recipients Using Unpatched Microsoft Zero-Day This weekend saw multiple reports a new zero-day vulnerability that affected all versions of Microsoft Word. -

Implications of Wikileaks Publishing Details of CIA's Cyber Arsenal

Implications of Wikileaks Publishing Details of CIA’s Cyber Arsenal ANKURA CONSULTING CYBERSECURITY & GEOPOLITICAL TEAMS CONSIDER THE FALLOUT OF WIKILEAKS’ REVELATIONS SUMMARY On Tuesday, March 7th, WikiLeaks, the whistle-blowing website run by Julian Assange, released a cache of Central In- telligence Agency (CIA) documents known as “Vault 7,” which contain details of CIA hacking tools. The cache included approximately 9,000 documents, dating from 2013 to 2016, which describe spyware, malware, and other tools allegedly used by the CIA to bypass encrypted messaging services by penetrating computer and mobile operating systems in- cluding Apple’s iOS and Google’s Android. It also suggests that developers can inject these tools without the owners’ knowledge, thus turning computers, network routers, smartphones, and web-enabled household appliances, electron- ics, and “smart” systems into remote spying devices. The documents also have the potential to reveal unprecedented detail about the CIA’s electronic spying tools at tremendous cost to US national security. It has been widely reported in the media that the CIA has identified Russian officials as having fed materials hacked from the Democratic National Committee to WikiLeaks. In fact, it has also been said that the US intelligence com- munity believes WikiLeaks has a relationship with Russian intelligence, even if WikiLeaks is simply being used as an outlet for leaked material damaging to the US. On September 7, in the aftermath of the Russian breach of the Democratic National Committee’s servers, James Clapper, ________________________________ then-director of national intelligence, stated, “The Russians hack our systems all the THE RUSSIANS HACK OUR time, not just government but also corporate and personal systems.” On March 20, SYSTEMS ALL THE TIME, FBI director James Comey confirmed the existence of an official investigation into the NOT JUST GOVERNMENT allegation that the Russians did in fact use cyber attacks to interfere in and influence BUT ALSO CORPORATE the outcome of the 2016 US Presidential election. -

Outsourcing in Intelligence and Defense Agencies: a Risk of an Increase in the Proliferation of Cyber Weapons?

Outsourcing in Intelligence and Defense Agencies: A Risk of an Increase in the Proliferation of Cyber Weapons? Omree Wechsler The many cases of the leakage of classified materials belonging to intelligence and defense agencies have led to claims that contract workers are the reason for these incidents, due to either their lack of loyalty or negligence. In addition, these leaks of classified information, including hacking programs and components, have raised the question of whether this internal threat is also the cause of the increased proliferation of sophisticated cyber weapons among players who do not have the ability to develop them. A prominent case study from the past few years is the leak of the National Security Agency (NSA)’s hacking component, EternalBlue, and its use in the global cyberattack WannaCry, which damaged computers in 150 countries and was attributed to North Korea. Understanding the internal threat and its connection to the proliferation of cyber weapons, along with enumerating the advantages and disadvantages of hiring contractors, is critical for minimizing the threat, coping with it, and in preventing harm to national security and further deterioration of stability in cyberspace. Keywords: Outsourcing, proliferation of cyber weapons, intelligence, contractors, information security Omree Wechsler is head of Cyber Research at the Yuval Ne’eman Workshop for Science, Technology, and Security and at the Blavatnik Inter-Disciplinary Cyber Research Center at Tel Aviv University. Cyber, Intelligence, and Security | Volume 3 | No. 1 | May 2019 95 OMREE WECHSLER | Outsourcing IN INTELLIGENCE AND DEFENSE AGENCIES 96 Introduction Much has been said about the disadvantages of outsourcing and privatizing of non-cybernetic security functions and services, which include problems of ethics and accountability when transferring the authority to use force into the hands of private companies. -

Powerhammer: Exfiltrating Data from Air-Gapped Computers Through Power Lines

PowerHammer: Exfiltrating Data from Air-Gapped Computers through Power Lines Mordechai Guri, Boris Zadov, Dima Bykhovsky, Yuval Eloviciz Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Israel Cyber-Security Research Center zDepartment of Software and Information Systems Engineering Email: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract—In this paper we provide an implementation, eval- a secured computer network in which measures are taken uation, and analysis of PowerHammer, a malware (bridgeware to maintain both physical and logical separation from less [1]) that uses power lines to exfiltrate data from air-gapped secured networks. The air-gap separation is maintained by computers. In this case, a malicious code running on a com- promised computer can control the power consumption of the enforcing strict regulations such as prohibiting connectivity system by intentionally regulating the CPU utilization. Data is to unauthorized equipment and hardening the workstations in modulated, encoded, and transmitted on top of the current flow the network. Today, air-gapped networks are used in military fluctuations, and then it is conducted and propagated through and defense systems, critical infrastructure, the finance sector, the power lines. This phenomena is known as a ’conducted and other industries [5], [6]. Two examples of air-gapped emission’. We present two versions of the attack. Line level power- hammering: In this attack, the attacker taps the in-home power networks are the United States Defense Intelligence Agencys lines1 that are directly attached to the electrical outlet. Phase level NSANET and Joint Worldwide Intelligence Communications power-hammering: In this attack, the attacker taps the power System (JWICS) classified networks [7].