5A1404ba4.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

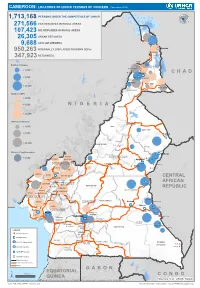

Page 1 C H a D N I G E R N I G E R I a G a B O N CENTRAL AFRICAN

CAMEROON: LOCATIONS OF UNHCR PERSONS OF CONCERN (November 2019) 1,713,168 PERSONS UNDER THE COMPETENCENIGER OF UNHCR 271,566 CAR REFUGEES IN RURAL AREAS 107,423 NIG REFUGEES IN RURAL AREAS 26,305 URBAN REFUGEES 9,688 ASYLUM SEEKERS 950,263 INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS (IDPs) Kousseri LOGONE 347,923 RETURNEES ET CHARI Waza Limani Magdeme Number of refugees EXTRÊME-NORD MAYO SAVA < 3,000 Mora Mokolo Maroua CHAD > 5,000 Minawao DIAMARÉ MAYO TSANAGA MAYO KANI > 20,000 MAYO DANAY MAYO LOUTI Number of IDPs < 2,000 > 5,000 NIGERIA BÉNOUÉ > 20,000 Number of returnees NORD < 2,000 FARO MAYO REY > 5,000 Touboro > 20,000 FARO ET DÉO Beke chantier Ndip Beka VINA Number of asylum seekers Djohong DONGA < 5,000 ADAMAOUA Borgop MENCHUM MANTUNG Meiganga Ngam NORD-OUEST MAYO BANYO DJEREM Alhamdou MBÉRÉ BOYO Gbatoua BUI Kounde MEZAM MANYU MOMO NGO KETUNJIA CENTRAL Bamenda NOUN BAMBOUTOS AFRICAN LEBIALEM OUEST Gado Badzere MIFI MBAM ET KIM MENOUA KOUNG KHI REPUBLIC LOM ET DJEREM KOUPÉ HAUTS PLATEAUX NDIAN MANENGOUBA HAUT NKAM SUD-OUEST NDÉ Timangolo MOUNGO MBAM ET HAUTE SANAGA MEME Bertoua Mbombe Pana INOUBOU CENTRE Batouri NKAM Sandji Mbile Buéa LITTORAL KADEY Douala LEKIÉ MEFOU ET Lolo FAKO AFAMBA YAOUNDE Mbombate Yola SANAGA WOURI NYONG ET MARITIME MFOUMOU MFOUNDI NYONG EST Ngarissingo ET KÉLLÉ MEFOU ET HAUT NYONG AKONO Mboy LEGEND Refugee location NYONG ET SO’O Refugee Camp OCÉAN MVILA UNHCR Representation DJA ET LOBO BOUMBA Bela SUD ET NGOKO Libongo UNHCR Sub-Office VALLÉE DU NTEM UNHCR Field Office UNHCR Field Unit Region boundary Departement boundary Roads GABON EQUATORIAL 100 Km CONGO ± GUINEA The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Sources: Esri, USGS, NOAA Source: IOM, OCHA, UNHCR – Novembre 2019 Pour plus d’information, veuillez contacter Jean Luc KRAMO ([email protected]). -

Africanprogramme for Onchocerctasts Control (Apoc)

RESERVED FOR PROTECT LOGO/HEADING COUNTRYAIOTF: CAMEROON Proiect Name: CDTI SW 2 Approval vearz 1999 Launchins vegr: 2000 Renortins Period: From: JANUARY 2008 To: DECEMBER 2008 (Month/Year) ( Mont!{eq) Proiectvearofthisrenort: (circleone) I 2 3 4 5 6 7(8) 9 l0 Date submitted: NGDO qartner: "l"""uivFzoog Sightsavers International South West 2 CDTI Project Report 2008 - Year 8. ANNUAL PROJECT TECHNICAL REPORT SUBMITTED TO TECHNICAL CONSULTATTVE COMMITTEE (TCC) DEADLINE FOR SUBMISSION: To APOC Management by 3l January for March TCC meeting To APOC Management by 31 Julv for September TCC meeting AFRICANPROGRAMME FOR ONCHOCERCTASTS CONTROL (APOC) I I RECU LE I S F[,;, ?ur], APOC iDIR ANNUAL I'II().I Ii(]'I"IIICHNICAL REPORT 't'o TECHNICAL CONSU l.',l'A]'tvE CoMMITTEE (TCC) ENDORSEMENT Please confirm you have read this report by signing in the appropriat space. OFFICERS to sign the rePort: Country: CAMEROON National Coordinator Name: Dr. Ntep Marcelline S l) u b Date: . ..?:.+/ c Ail 9ou R Regional Delegate Name: Dr. Chu + C( z z a tu Signature: n rJ ( Date 6t @ RY oF I DE LA NGDO Representative Name: Dr. Oye Joseph E Signature: .... Date:' g 2 JAN. u0g Regional Oncho Coordinator Name: Mr. Ebongo Signature: Date: 51-.12-Z This report has been prepared by Name : Mr. Ebongo Peter Designation:.OPC SWII Signature: *1.- ,l 1l Table of contents Acronyms .v Definitions vi FOLLOW UP ON TCC RECOMMENDATIONS. 7 Executive Summary.. 8 SECTION I : Background information......... 9 1.1. GrrueRruINFoRMATroN.................... 9 1.1.1 Description of the project...... 9 Location..... 9 1. 1. 2. -

Dictionnaire Des Villages Du Fako : Village Dictionary of Fako Division

OFFICE DE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIOUE ET TECHNIOUE OUTRE· MER Il REPUBLIQUE UNIE DU CAMEROUN DICTIONNAIRE DES VILLAGES DU FAKO VILLAGE DICTIONARY OF FAKO DIVISION SECTION DE GEOGRAPHIE 1 OFFICE DE LA RECHERCHE SCIm~TIFIQUE REPUBLIQUE UNIE ET TECmUQUE OUTRE-lViER DU CAlvŒROUN UNITED REPUBLIC OF CANEROON CENTRE O.R.S.T.O.N DE YAOUNDE DICTIONNAIRE DES VILLAGES DU FAKO VILLAGE DICTIONARY OF FAKO DIVISION Juillet 1973 July 1973 COPYRIGHT O.R.S.T.O.M 1973 TABLE DES NATIERES CONTENTS i l j l ! :i i ~ Présentation •••••.•.•.....••....•.....•....••••••.••.••••••.. 1 j Introduction ........................................•• 3 '! ) Signification des principaux termes utilisés •.............• 5 î l\lIeaning of the main words used Tableau de la population du département •...••.....•..•.•••• 8 Population of Fako division Département du Fako : éléments de démographie •.•.... ..••.•• 9 Fako division: demographic materials Arrondissements de Muyuka et de Tiko : éléments de . démographie 0 ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 10 11uyul{a and Tileo sl)..bdivisions:demographic materials Arrondissement de Victoria: éléments de démographie •••.••• 11 Victoria subdivision:demographic materials Les plantations (12/1972) •••••••••••.•••••••••••••••••••••• 12 Plantations (12/1972) Liste des villages par arrondissement, commune et graupement 14 List of villages by subdivision, area council and customary court Signification du code chiffré •..•••...•.•...•.......•.•••.• 18 Neaning of the code number Liste alphabétique des villages ••••••.••••••••.•.•..•••.•.• 19 -

Shelter Cluster Dashboard NWSW052021

Shelter Cluster NW/SW Cameroon Key Figures Individuals Partners Subdivisions Cameroon 03 23,143 assisted 05 Individual Reached Trend Nigeria Furu Awa Ako Misaje Fungom DONGA MANTUNG MENCHUM Nkambe Bum NORD-OUEST Menchum Nwa Valley Wum Ndu Fundong Noni 11% BOYO Nkum Bafut Njinikom Oku Kumbo Belo BUI Mbven of yearly Target Njikwa Akwaya Jakiri MEZAM Babessi Tubah Reached MOMO Mbeggwi Ngie Bamenda 2 Bamenda 3 Ndop Widikum Bamenda 1 Menka NGO KETUNJIA Bali Balikumbat MANYU Santa Batibo Wabane Eyumodjock Upper Bayang LEBIALEM Mamfé Alou OUEST Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Fontem Nguti KOUPÉ HNO/HRP 2021 (NW/SW Regions) Toko MANENGOUBA Bangem Mundemba SUD-OUEST NDIAN Konye Tombel 1,351,318 Isangele Dikome value Kumba 2 Ekondo Titi Kombo Kombo PEOPLE OF CONCERN Abedimo Etindi MEME Number of PoC Reached per Subdivision Idabato Kumba 1 Bamuso 1 - 100 Kumba 3 101 - 2,000 LITTORAL 2,001 - 13,000 785,091 Mbongé Muyuka PEOPLE IN NEED West Coast Buéa FAKO Tiko Limbé 2 Limbé 1 221,642 Limbé 3 [ Kilometers PEOPLE TARGETED 0 15 30 *Note : Sources: HNO 2021 PiN includes IDP, Returnees and Host Communi�es The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Key Achievement Indicators PoC Reached - AGD Breakdouwn 296 # of Households assisted with Children 27% 26% emergency shelter 1,480 Adults 21% 22% # of households assisted with core 3,769 Elderly 2% 2% relief items including prevention of COVID-19 21,618 female male 41 # of households assisted with cash for rental subsidies 41 Households Reached Individuals Reached Cartegories of beneficiaries reported People Reached by region Distribution of Shelter NFI kits integrated with COVID 19 KITS in Matoh town. -

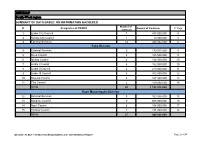

MINMAP South-West Region

MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts 1 Limbe City Council 7 475 000 000 4 2 Kumba City Council 1 10 000 000 5 3 External Services 14 440 032 000 6 Fako Division 4 External Services 9 179 015 000 8 5 Buea Council 5 125 500 000 9 6 Idenau Council 4 124 000 000 10 7 Limbe I Council 4 152 000 000 10 8 Limbe II Council 4 219 000 000 11 9 Limbe III Council 6 102 500 000 12 10 Muyuka Council 6 127 000 000 13 11 Tiko Council 5 159 000 000 14 TOTAL 43 1 188 015 000 Kupe Muanenguba Division 12 External Services 5 100 036 000 15 13 Bangem Council 9 605 000 000 15 14 Nguti Council 6 104 000 000 17 15 Tombel Council 7 131 000 000 18 TOTAL 27 940 036 000 MINMAP / PUBLIC CONTRACTS PROGRAMMING AND MONITORING DIVISION Page 1 of 34 MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Lebialem Division 16 External Services 5 134 567 000 19 17 Alou Council 9 144 000 000 19 18 Menji Council 3 181 000 000 20 19 Wabane Council 9 168 611 000 21 TOTAL 26 628 178 000 Manyu Division 18 External Services 5 98 141 000 22 19 Akwaya Council 6 119 500 000 22 20 Eyomojock Council 6 119 000 000 23 21 Mamfe Council 5 232 000 000 24 22 Tinto Council 6 108 000 000 25 TOTAL 28 676 641 000 Meme Division 22 External Services 5 85 600 000 26 23 Mbonge Council 7 149 000 000 26 24 Konye Council 1 27 000 000 27 25 Kumba I Council 3 65 000 000 27 26 Kumba II Council 5 83 000 000 28 27 Kumba III Council 3 84 000 000 28 TOTAL 24 493 600 000 MINMAP / PUBLIC CONTRACTS -

South West Assessment

Cameroon Emergency Response – South West Assessment SOUTH WEST CAMEROON November 2018 – January 2019 - i - CONTENTS 1 CONTEXT ..................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 The crisis in numbers:.................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Overall Objectives of SW Assessment ........................................................................... 5 1.3 Area of Intervention ...................................................................................................... 6 2 METHODOLOGY .......................................................................................................... 6 2.1 Assessment site selection: ............................................................................................ 8 2.2 Configuration of the assessment team: ........................................................................ 8 2.3 Indicators of vulnerability verified during the rapid assessment: ................................ 9 2.3.1 Nutrition and Health ............................................................................................. 9 2.3.2 WASH ..................................................................................................................... 9 3.1.1 Food Security ......................................................................................................... 9 2.4 Sources of Information ............................................................................................... -

Assessing Cost Efficiency Among Small Scale Rice Producers in the West Region of Cameroon: a Stochastic Frontier Model Approach

International Journal of Humanities Social Sciences and Education (IJHSSE) Volume 3, Issue 6, June 2016, PP 1-7 ISSN 2349-0373 (Print) & ISSN 2349-0381 (Online) http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2349-0381.0306001 www.arcjournals.org Assessing Cost Efficiency among Small Scale Rice Producers in the West Region of Cameroon: A Stochastic Frontier Model Approach Djomo, Raoul Fani*1, Ewung, Bethel1, Egbeadumah, Maryanne Odufa2 1Department of Agricultural Economics. University of Agriculture, Makurdi. Benue-State, Nigeria PMB 2373, Makurdi 2Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension, Federal University Wukari, PMB 1020 Wukari. Taraba State, Nigeria *[email protected] Abstract: Local farmers’ techniques and knowledge in rice cultivation being deficient and the aid system and research to support such farmers’ activities likewise insufficient, technological progress and increase in rice production are not yet assured. Therefore, this Study was undertaken to assess cost efficiency among small scale rice farmers in the West Region of Cameroon using stochastic frontier model approach. A purposive, multistage and stratified random sampling technique was used in selecting the respondents. A total of 192 small scale rice farmers were purposively selected from four (4) out of eight divisions. Data were collected using structured questionnaires and interview schedule, administered on the respondents were analyzed using descriptive statistics and stochastic frontier cost functions. The result indicates that the coefficient of cost of labour was found positive and significantly influence cost of production in small scale rice production at 1 percent level of probability, implying that increases in cost of labour by one unit will also increase cost of production in small scale rice farming by the value of it coefficient. -

N I G E R I a C H a D Central African Republic Congo

CAMEROON: LOCATIONS OF UNHCR PERSONS OF CONCERN (September 2020) ! PERSONNES RELEVANT DE Maïné-Soroa !Magaria LA COMPETENCE DU HCR (POCs) Geidam 1,951,731 Gashua ! ! CAR REFUGEES ING CurAi MEROON 306,113 ! LOGONE NIG REFUGEES IN CAMEROON ET CHARI !Hadejia 116,409 Jakusko ! U R B A N R E F U G E E S (CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC AND 27,173 NIGERIAN REFUGEE LIVING IN URBAN AREA ARE INCLUDED) Kousseri N'Djamena !Kano ASYLUM SEEKERS 9,332 Damaturu Maiduguri Potiskum 1,032,942 INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSO! NS (IDPs) * RETURNEES * Waza 484,036 Waza Limani Magdeme Number of refugees MAYO SAVA Mora ! < 10,000 EXTRÊME-NORD Mokolo DIAMARÉ Biu < 50,000 ! Maroua ! Minawao MAYO Bauchi TSANAGA Yagoua ! Gom! be Mubi ! MAYO KANI !Deba MAYO DANAY < 75000 Kaele MAYO LOUTI !Jos Guider Number! of IDPs N I G E R I A Lafia !Ləre ! < 10,000 ! Yola < 50,000 ! BÉNOUÉ C H A D Jalingo > 75000 ! NORD Moundou Number of returnees ! !Lafia Poli Tchollire < 10,000 ! FARO MAYO REY < 50,000 Wukari ! ! Touboro !Makurdi Beke Chantier > 75000 FARO ET DÉO Tingere ! Beka Paoua Number of asylum seekers Ndip VINA < 10,000 Bocaranga ! ! Borgop Djohong Banyo ADAMAOUA Kounde NORD-OUEST Nkambe Ngam MENCHUM DJEREM Meiganga DONGA MANTUNG MAYO BANYO Tibati Gbatoua Wum BOYO MBÉRÉ Alhamdou !Bozoum Fundong Kumbo BUI CENTRAL Mbengwi MEZAM Ndop MOMO AFRICAN NGO Bamenda KETUNJIA OUEST MANYU Foumban REPUBLBICaoro BAMBOUTOS ! LEBIALEM Gado Mbouda NOUN Yoko Mamfe Dschang MIFI Bandjoun MBAM ET KIM LOM ET DJEREM Baham MENOUA KOUNG KHI KOUPÉ Bafang MANENGOUBA Bangangte Bangem HAUT NKAM Calabar NDÉ SUD-OUEST -

Evaluating the Constraints and Opportunities of Maize Production in the West Region of Cameroon for Sustainable Development

Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa (Volume 13, No.4, 2011) ISSN: 1520-5509 Clarion University of Pennsylvania, Clarion, Pennsylvania EVALUATING THE CONSTRAINTS AND OPPORTUNITIES OF MAIZE PRODUCTION IN THE WEST REGION OF CAMEROON FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT Godwin Anjeinu Abu1, Raoul Fani Djomo-Choumbou1 and Stephen Adogwu Okpachu2 1. Department of Agricultural Economics, University of Agriculture PMB 2373, Makurdi Benue State- Nigeria 2. Federal College of Education (Technical), Potiskum, Yobe State, Nigeria ABSTRACT A study of Evaluating the constraints and opportunities of Maize production in the West Region of Cameroon was carried out using primary and secondary data collected. One hundred and twenty (120) maize farmers randomly selected from eight (8) villages were interviewed using structured questionnaire. Data from the study were analyzed using descriptive statistics such as frequency distribution, percentages, and inferential statistics such as multiple linear regressions. The study found that most maize farmers in the study area were small scale farmers and are full time farmers, the major maize production constraints was poor access to credit facilities. it was also found any unit increase in the quantity of any of the resources used for maize production will increase maize output by the value of their estimated coefficients respectively , however to raise maize production, the study recommend that financial institutions such as agricultural and community banks should be established in the study area with the simple procedure of securing loans. The relevant government agencies and non- governmental organization should mobilize the maize farmers to form themselves into formidable group so that they can derive maximum benefit of collective union. -

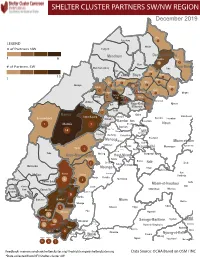

NW SW Presence Map Complete Copy

SHELTER CLUSTER PARTNERS SW/NWMap creation da tREGIONe: 06/12/2018 December 2019 Ako Furu-Awa 1 LEGEND Misaje # of Partners NW Fungom Menchum Donga-Mantung 1 6 Nkambe Nwa 3 1 Bum # of Partners SW Menchum-Valley Ndu Mayo-Banyo Wum Noni 1 Fundong Nkum 15 Boyo 1 1 Njinikom Kumbo Oku 1 Bafut 1 Belo Akwaya 1 3 1 Njikwa Bui Mbven 1 2 Mezam 2 Jakiri Mbengwi Babessi 1 Magba Bamenda Tubah 2 2 Bamenda Ndop Momo 6b 3 4 2 3 Bangourain Widikum Ngie Bamenda Bali 1 Ngo-Ketunjia Njimom Balikumbat Batibo Santa 2 Manyu Galim Upper Bayang Babadjou Malentouen Eyumodjock Wabane Koutaba Foumban Bambo7 tos Kouoptamo 1 Mamfe 7 Lebialem M ouda Noun Batcham Bafoussam Alou Fongo-Tongo 2e 14 Nkong-Ni BafouMssamif 1eir Fontem Dschang Penka-Michel Bamendjou Poumougne Foumbot MenouaFokoué Mbam-et-Kim Baham Djebem Santchou Bandja Batié Massangam Ngambé-Tikar Nguti Koung-Khi 1 Banka Bangou Kekem Toko Kupe-Manenguba Melong Haut-Nkam Bangangté Bafang Bana Bangem Banwa Bazou Baré-Bakem Ndé 1 Bakou Deuk Mundemba Nord-Makombé Moungo Tonga Makénéné Konye Nkongsamba 1er Kon Ndian Tombel Yambetta Manjo Nlonako Isangele 5 1 Nkondjock Dikome Balue Bafia Kumba Mbam-et-Inoubou Kombo Loum Kiiki Kombo Itindi Ekondo Titi Ndikiniméki Nitoukou Abedimo Meme Njombé-Penja 9 Mombo Idabato Bamusso Kumba 1 Nkam Bokito Kumba Mbanga 1 Yabassi Yingui Ndom Mbonge Muyuka Fiko Ngambé 6 Nyanon Lekié West-Coast Sanaga-Maritime Monatélé 5 Fako Dibombari Douala 55 Buea 5e Massock-Songloulou Evodoula Tiko Nguibassal Limbe1 Douala 4e Edéa 2e Okola Limbe 2 6 Douala Dibamba Limbe 3 Douala 6e Wou3rei Pouma Nyong-et-Kellé Douala 6e Dibang Limbe 1 Limbe 2 Limbe 3 Dizangué Ngwei Ngog-Mapubi Matomb Lobo 13 54 1 Feedback: [email protected]/ [email protected] Data Source: OCHA Based on OSM / INC *Data collected from NFI/Shelter cluster 4W. -

Cameroon:NW/SW Highlights Needs 690K 414K 679K1 52 $9.5M

Cameroon:NW/SW WASH Update Hand-washing sensitization in Bamenda II. Photo by WA Cameroon. September 2020 Highlights Needs In August, more than 28,800 people were reached with various WASH services 690k People in need of WASH conducted by eight WASH partners services in NW/SW namely ASWEDO, CHAMEG, EPDA, GCR, H4BF, IRC, NRC and SUDAHSER. 414k Targeted WASH partners reached 7,000 people through hygiene promotion sessions while 679k1 IDPs over 9,200 individuals were reached through COVID-19 sensitization activities. 52 WASH partners In September, more than 330 households in Bamenda 1, 2, 3 and Limbe 1 sub- $9.5m divisions benefited from distribution of WASH kits by NRC and SUDAHSER required for WASH $9.5m EPDA, in collaboration with UNICEF, constructed 42 emergency latrines that are expected to benefit at least 8,300 people in Fako and Ndian sub-divisions. $0.2M Required Funded 1 Cameroon: OCHA NW/SW Situation Report No.22, 2020 Website: https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/operations/cameroon/water-sanitation-hygiene For more information contact Wash Cluster Coordinator: Nchunguye Festo Vyagusa Email: [email protected] Information Management Officer: Stan Mverechena, Email [email protected] WATER In Bui (North West) and Ndian (South West), SUDAHSER formed and trained four water user committees whose responsibility is to ensure that water, sanitation and hygiene standards are maintained. CHAMEG conducted a training that was attended by 36 water user committee members in Buea, Fako division. In Wovia village, Limbe II sub-division of South West region, EPDA constructed a safe spring water catchment that will benefit at least 500 people. -

African Development Bank Group

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP PROJECT : TRANSPORT SECTOR SUPPORT PROGRAMME PHASE 2 : REHABILITATION OF YAOUNDE-BAFOUSSAM- BAMENDA ROAD – DEVELOPMENT OF THE GRAND ZAMBI-KRIBI ROAD – DEVELOPMENT OF THE MAROUA-BOGO-POUSS ROAD COUNTRY : REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON SUMMARY FULL RESETTLEMENT PLAN (FRP) Team Leader J. K. NGUESSAN, Chief Transport Engineer OITC.1 P. MEGNE, Transport Economist OITC.1 P.H. SANON, Socio-Economist ONEC.3 M. KINANE, Environmentalist ONEC.3 S. MBA, Senior Transport Engineer OITC.1 T. DIALLO, Financial Management Expert ORPF.2 C. DJEUFO, Procurement Specialist ORPF.1 Appraisal Team O. Cheick SID, Consultant OITC.1 Sector Director A. OUMAROU OITC Regional Director M. KANGA ORCE Resident CMFO R. KANE Representative Sector Division OITC.1 J.K. KABANGUKA Manager 1 Project Name : Transport Sector Support Programme Phase 2 SAP Code: P-CM-DB0-015 Country : Cameroon Department : OITC Division : OITC-1 1. INTRODUCTION This document is a summary of the Abbreviated Resettlement Plan (ARP) of the Transport Sector Support Programme Phase 2. The ARP was prepared in accordance with AfDB requirements as the project will affect less than 200 people. It is an annex to the Yaounde- Bafoussam-Babadjou road section ESIA summary which was prepared in accordance with AfDB’s and Cameroon’s environmental and social assessment guidelines and procedures for Category 1 projects. 2. PROJECT DESCRIPTION, LOCATION AND IMPACT AREA 2.1.1 Location The Yaounde-Bafoussam-Bamenda road covers National Road 4 (RN4) and sections of National Road 1 (RN1) and National Road 6 (RN6) (Figure 1). The section to be rehabilitated is 238 kilometres long. Figure 1: Project Location Source: NCP (2015) 2 2.2 Project Description and Rationale The Yaounde-Bafoussam-Bamenda (RN1-RN4-RN6) road, which was commissioned in the 1980s, is in an advanced state of degradation (except for a few recently paved sections between Yaounde and Ebebda, Tonga and Banganté and Bafoussam-Mbouda-Babadjou).