Integrated Coastal Zone Management in Spain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

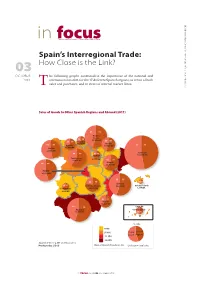

In Focusthe Barcelona Centre for International Affairs Brief

CIDOB • Barcelona Centre for International 2012 for September Affairs. Centre CIDOB • Barcelona in focusThe Barcelona Centre for International Affairs Brief Spain’s Interregional Trade: 03 How Close is the Link? OCTOBER he following graphs contextualise the importance of the national and 2012 international market for the 17 dif ferent Spanish regions, in terms of both T sales and purchases, and in terms of internal market flows. Sales of Goods to Other Spanish Regions and Abroad (2011) 46 54 Basque County 36 64 45,768 M€ 33 67 Cantabria 45 55 7,231 M€ Navarre 54 46 Asturias 17,856 M€ 53 47 Galicia 11,058 M€ 32,386 M€ 40 60 31 69 Catalonia La Rioja 104,914 M€ Castile-Leon 4,777 M€ 30,846 M€ 39 61 Aragon 54 46 23,795 M€ Madrid 45,132 M€ 45 55 22 78 5050 Valencia 29 71 Castile-La Mancha 44,405 M€ Balearic Islands Extremaura 18,692 M€ 1,694 M€ 4,896 M€ 39 61 Murcia 14,541 M€ 44 56 4,890 M€ Andalusia Canary Islands 52,199 M€ 49 51 % Sales 0-4% 5-10% To the Spanish World Regions 11-15% 16-20% Source: C-Intereg, INE and Datacomex Produced by: CIDOB Share of Spanish Population (%) Circle Size = Total Sales in focus CIDOB 03 . OCTOBER 2012 CIDOB • Barcelona Centre for International 2012 for September Affairs. Centre CIDOB • Barcelona Purchase of Goods From Other Spanish Regions and Abroad (2011) Basque County 28 72 36 64 35,107 M€ 35 65 Asturias Cantabria Navarre 11,580 M€ 55 45 6,918 M€ 14,914 M€ 73 27 Galicia 29 71 25,429 M€ 17 83 Catalonia Castile-Leon La Rioja 97,555 M€ 34,955 M€ 29 71 6,498 M€ Aragon 67 33 26,238 M€ Madrid 79,749 M€ 44 56 2 78 Castile-La Mancha Valencia 19 81 12 88 23,540 M€ Extremaura 49 51 45,891 M€ Balearic Islands 8,132 M€ 8,086 M€ 54 46 Murcia 18,952 M€ 56 44 Andalusia 52,482 M€ Canary Islands 35 65 13,474 M€ Purchases from 27,000 to 31,000 € 23,000 to 27,000 € Rest of Spain 19,000 to 23,000 € the world 15,000 to 19,000 € GDP per capita Circle Size = Total Purchase Source: C-Intereg, Expansión and Datacomex Produced by: CIDOB 2 in focus CIDOB 03 . -

“Isla Cristina Por La Salud” ISLA CRISTINA 2017-2020

“Isla Cristina por la Salud” ISLA CRISTINA 2017-2020 AYUNTAMIENTO DE ISLA CRISTINA Ayuntamiento de Isla Cristina “Isla Cristina por la Salud” Dirección D. Natanael López Mirabent Concejal de Sanidad - Ayuntamiento de Isla Cristina Coordinación Dña. Teresa J. López Mingorance Técnica Sanidad Ayuntamiento de Isla Cristina Dña. Inmaculada Brito Pérez Técnica en Prevención de Drogas Ayuntamiento de Isla Cristina D. Isidoro Durán Cortés Técnico en Acción Local en Salud Pública. Delegación P. de Igualdad, Salud y Políticas Sociales de Huelva Nota: Los datos de carácter personal recogidos en el documento cumple con la ley vigente de protección datos española Ley Orgánica 15/1999 de 13 de diciembre de Protección de Datos de Carácter Personal, (LOPD) Real Decreto 1720/2007, de 21 de diciembre de desarrollo de la Ley Orgánica de Protección de Datos 2 “Isla Cristina por la Salud” PRESENTACIÓN SALUDA DE LA ALCALDESA Tras varios años de trabajo, el Plan Local de Salud de Isla Cristina ve la luz y como Alcaldesa supone una inmensa satisfacción haber conseguido que este proyecto, fruto del arduo trabajo de la Delegación de Salud del Ayuntamiento junto a otros muchos agentes locales, sea una realidad y comience a funcionar para el beneficio de todas y todos los isleños. Este Plan nace en el marco del proyecto RELAS cuya finalidad es la de articular una red local de acción en salud de la que se beneficien el conjunto de los isleños y nuestro pueblo se suma a la red de municipios de Andalucía donde se ha puesto en marcha esta interesante iniciativa que viene a reportar una mayor calidad de vida a los ciudadanos a través de acciones destinadas a promover hábitos saludables, participación ciudadana y formación en valores. -

Nerin-En.Pdf

FOLLOWING THE FOOTPRINTS OF COLONIAL BARCELONA Gustau Nerín It is hardly unusual to find people, even highly educated people, who claim Catalonia can analyse colonialism with sufficient objectivity given that it has never taken part in any colonial campaign and never been colonialist. Even though most historians do not subscribe to this view, it is certainly a common belief among ordinary people. Dissociating ourselves from colonialism is obviously a way of whitewashing our history and collective conscience. But Barcelona, like it or not, is a city that owes a considerable amount of its growth to its colonial experience. First, it is obvious that the whole of Europe was infected with colonial attitudes at the height of the colonial period, towards the end of the 19th century and first half of the 20th. Colonial beliefs were shared among the English, French, Portuguese and Belgians, as well as the Swedes, Swiss, Italians, Germans and Catalans. Colonialist culture was constantly being consumed in Barcelona as in the rest of Europe. People were reading Jules Verne’s and Emilio Salgari's novels, collecting money for the “poor coloured folk” at missions in China and Africa and raising their own children with the racist poems of Kipling. The film industry, that great propagator of colonial myths, inflamed passions in our city with Tarzan, Beau Geste and The Four Feathers. Barcelona’s citizens certainly shared this belief in European superiority and in the white man’s burden, with Parisians, Londoners and so many other Europeans. In fact, even the comic strip El Capitán Trueno, which was created by a communist Catalan, Víctor Mora, proved to be a perfect reflection of these colonial stereotypes. -

The Beginning of the Neolithic in Andalusia

Quaternary International xxx (2017) 1e21 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quaint The beginning of the Neolithic in Andalusia * Dimas Martín-Socas a, , María Dolores Camalich Massieu a, Jose Luis Caro Herrero b, F. Javier Rodríguez-Santos c a U.D.I. de Prehistoria, Arqueología e Historia Antigua (Dpto. Geografía e Historia), Universidad de La Laguna, Campus Guajara, 38071 Tenerife, Spain b Dpto. Lenguajes y Ciencias de la Computacion, Universidad de Malaga, Complejo Tecnologico, Campus de Teatinos, 29071 Malaga, Spain c Instituto Internacional de Investigaciones Prehistoricas de Cantabria (IIIPC), Universidad de Cantabria. Edificio Interfacultativo, Avda. Los Castros, 52. 39005 Santander, Spain article info abstract Article history: The Early Neolithic in Andalusia shows great complexity in the implantation of the new socioeconomic Received 31 January 2017 structures. Both the wide geophysical diversity of this territory and the nature of the empirical evidence Received in revised form available hinder providing a general overview of when and how the Mesolithic substrate populations 6 June 2017 influenced this process of transformation, and exactly what role they played. The absolute datings Accepted 22 June 2017 available and the studies on the archaeological materials are evaluated, so as to understand the diversity Available online xxx of the different zones undergoing the neolithisation process on a regional scale. The results indicate that its development, initiated in the middle of the 6th millennium BC and consolidated between 5500 and Keywords: Iberian Peninsula 4700 cal. BC, is parallel and related to the same changes documented in North Africa and the different Andalusia areas of the Central-Western Mediterranean. -

Cantabria Y Asturias Seniors 2016·17

Cantabria y Asturias Seniors 2016·17 7 días / 6 noches Hotel Zabala 3* (Santillana del Mar) € Hotel Norte 3* (Gijón) desde 399 Salida: 11 de junio Precio por persona en habitación doble Suplemento Hab. individual: 150€ ¡TODO INCLUIDO! 13 comidas + agua/vino + excursiones + entradas + guías ¿Por qué reservar este viaje? ¿Quiere conocer Cantabria y Asturias? En nuestro circuito Reserve por sólo combinamos lo mejor de estas dos comunidades para que durante 7 días / 6 noches conozcas a fondo los mejores rincones de la geografía. 50 € Itinerario: Incluimos: DÍA 1º. BARCELONA – CANTABRIA • Asistencia por personal de Viajes Tejedor en el punto de salida. Salida desde Barcelona. Breves paradas en ruta (almuerzo en restaurante incluido). • Autocar y guía desde Barcelona y durante todo el recorrido. Llegada al hotel en Cantabria. Cena y alojamiento. • 3 noches de alojamiento en el hotel Zabala 3* de Santillana del Mar y 2 noches en el hotel Norte 3* de Gijón. DÍA 2º. VISITA DE SANTILLANA DEL MAR y COMILLAS – VISITA DE • 13 comidas con agua/vino incluido, según itinerario. SANTANDER • Almuerzos en ruta a la ida y regreso. Desayuno. Seguidamente nos dirigiremos a la localidad de Santilla del Mar. Histórica • Visitas a: Santillana del Mar, Comillas, Santander, Santoña, Picos de Europa, Potes, población de gran belleza, donde destaca la Colegiata románica del S.XII, declarada Oviedo, Villaviciosa, Lastres, Tazones, Avilés, Luarca y Cudillero. Monumento Nacional. Las calles empedradas y las casas blasonadas, configuran un paisaje • Pasaje de barco de Santander a Somo. urbano de extraordinaria belleza. Continuaremos viaje a la cercana localidad de Comillas, • Guías locales en: Santander, Oviedo y Avilés. -

Benidorm Spain Travel Guide

Benidorm Costa Blanca - Spain Travel Guide by Doreen A. Denecker and Hubert Keil www.Alicante-Spain.com Free Benidorm Travel Guide This is a FREE ebook! Please feel free to : • Reprint this ebook • Copy this PDF File • Pass it on to your friends • Give it away to visitors of your website*) • or distribute it in anyway. The only restriction is that you are not allowed to modify, add or extract all or parts of this ebook in any way (that’s it). *) Webmaster! If you have your own website and/or newsletter, we offer further Costa Blanca and Spain material which you can use on your website for free. Please check our special Webmaster Info Page here for further information. DISCLAIMER AND/OR LEGAL NOTICES: The information presented herein represents the view of the author as of the date of publication. Be- cause of the rate with which conditions change, the author reserves the right to alter and update his opinion based on the new conditions. The report is for informational purposes only. While every at- tempt has been made to verify the information provided in this report, neither the author nor his affili- ates/partners assume any responsibility for errors, inaccuracies or omissions. Any slights of people or organizations are unintentional. If advice concerning legal or related matters is needed, the services of a fully qualified professional should be sought. This report is not intended for use as a source of legal or accounting advice. You should be aware of any laws which govern business transactions or other business practices in your country and state. -

To the West of Spanish Cantabria. the Palaeolithic Settlement of Galicia

To the West of Spanish Cantabria. The Palaeolithic Settlement of Galicia Arturo de Lombera Hermida and Ramón Fábregas Valcarce (eds.) Oxford: Archaeopress, 2011, 143 pp. (paperback), £29.00. ISBN-13: 97891407308609. Reviewed by JOÃO CASCALHEIRA DNAP—Núcleo de Arqueologia e Paleoecologia, Faculdade de Ciências Humanas e Sociais, Universidade do Algarve, Campus Gambelas, 8005- 138 Faro, PORTUGAL; [email protected] ompared with the rest of the Iberian Peninsula, Galicia investigation, stressing the important role of investigators C(NW Iberia) has always been one of the most indigent such as H. Obermaier and K. Butzer, and ending with a regions regarding Paleolithic research, contrasting pro- brief presentation of the projects that are currently taking nouncedly with the neighboring Cantabrian rim where a place, their goals, and auspiciousness. high number of very relevant Paleolithic key sequences are Chapter 2 is a contribution of Pérez Alberti that, from known and have been excavated for some time. a geomorphological perspective, presents a very broad Up- This discrepancy has been explained, over time, by the per Pleistocene paleoenvironmental evolution of Galicia. unfavorable geological conditions (e.g., highly acidic soils, The first half of the paper is constructed almost like a meth- little extension of karstic formations) of the Galician ter- odological textbook that through the definition of several ritory for the preservation of Paleolithic sites, and by the concepts and their applicability to the Galician landscape late institutionalization of the archaeological studies in supports the interpretations outlined for the regional inter- the region, resulting in an unsystematic research history. land and coastal sedimentary sequences. As a conclusion, This scenario seems, however, to have been dramatically at least three stadial phases were identified in the deposits, changed in the course of the last decade. -

Zona Sur - Fútbol Sala - Cadete Masculino

8/5/2020 LEVERADE La Provincia en Juego Zona Sur - Fútbol Sala - Cadete Masculino Grupo Único Calendario — Jornada 1 - 16/11/19 senoiccA odatsE senoicavresbO saci tsídatsE Equipo 1 Resultado Equipo 2 Árbitros Fecha Hora Lugar EDM Chucena – SMD Almonte A G EDM Villalba del Alcor 16 – 1 SMD Almonte B VILLALBA – ANTONIO MANUEL MARTÍNEZ SÁNCHEZ Sáb, 09/11/2019 11:00 Villalba del Alcor (Pabellón Mpal) G EDM Manzanilla 4 – 1 CD Isla Cristina Fútbol Sala MANZANILLA - JOSÉ MARÍA MATEOS GARCÍA Vie, 15/11/2019 19:00 Manzanilla (Polideportivo Mpal) G CD La Palma Fútbol Sala (ACT) 2 – 4 EDM Bollullos del Condado LA PALMA – JOSÉ MIGUEL LEPE ALONSO Jue, 28/11/2019 19:00 Palma del Condado, La (Polideportiv Grupo Único Calendario — Jornada 2 - 23/11/19 senoiccA odatsE senoicavresbO saci tsídatsE Equipo 1 Resultado Equipo 2 Árbitros Fecha Hora Lugar CD La Palma Fútbol Sala (ACT) – EDM Manzanilla G CD Isla Cristina Fútbol Sala 8 – 4 SMD Almonte B AYAMONTE - EMILIO SILVA PÉREZ Sáb, 23/11/2019 18:00 Isla Cristina (Polideportivo Mpal) G EDM Bollullos del Condado 7 – 11 EDM Chucena BOLLULLOS – MANUEL MATEO VALDERA Mié, 27/11/2019 16:30 Bollullos del Condado, El (Pabellón Mpal) SMD Almonte A 3 – 7 EDM Villalba del Alcor ALMONTE - JOSE MARÍA SOLIS EXPOSITO Vie, 07/02/2020 17:30 Almonte (Polideportivo Mpal) Grupo Único Calendario — Jornada 3 - 30/11/19 senoiccA odatsE senoicavresbO saci tsídatsE Equipo 1 Resultado Equipo 2 Árbitros Fecha Hora Lugar G EDM Villalba del Alcor 10 – 3 CD Isla Cristina Fútbol Sala VILLALBA – ANTONIO MANUEL MARTÍNEZ SÁNCHEZ Mié, 27/11/2019 -

Catalonian Architectural Identity

Catalan Identity as Expressed Through Architecture Devon G. Shifflett HIST 348-01: The History of Spain November 18, 2020 1 Catalonia (Catalunya) is an autonomous community in Spain with a unique culture and language developed over hundreds of years. This unique culture and language led to Catalans developing a concept of Catalan identity which encapsulates Catalonia’s history, cuisine, architecture, culture, and language. Catalan architects have developed distinctly Catalan styles of architecture to display Catalan identity in a public and physical setting; the resulting buildings serve as a physical embodiment of Catalan identity and signify spaces within Catalan cities as distinctly Catalonian. The major architectural movements that accomplish this are Modernisme, Noucentisme, and Postmodernism. These architectural movements have produced unique and beautiful buildings in Catalonia that serve as symbols for Catalan national unity. Catalonia’s long history, which spans thousands of years, contributes heavily to the development of Catalan identity and nationalism. Various Celtiberian tribes initially inhabited the region of Iberia that later became Catalonia.1 During the Second Punic War (218-201 BC), Rome began its conquest of the Iberian Peninsula, which was occupied by the Carthaginians and Celtiberians, and established significant colonies around the Pyrennees mountain range that eventually become Barcelona and Tarragona; it was during Roman rule that Christianity began to spread throughout Catalonia, which is an important facet of Catalan identity.2 Throughout the centuries following Roman rule, the Visigoths, Frankish, and Moorish peoples ruled Catalonia, with Moorish rule beginning to flounder in the tenth-century.3 Approximately the year 1060 marked the beginning of Catalan independence; throughout this period of independence, Catalonia was very prosperous and contributed heavily to the Reconquista.4 This period of independence did not last long, though, with Catalonia and Aragon's union beginning in 1 Thomas N. -

Chapter 24. the BAY of BISCAY: the ENCOUNTERING of the OCEAN and the SHELF (18B,E)

Chapter 24. THE BAY OF BISCAY: THE ENCOUNTERING OF THE OCEAN AND THE SHELF (18b,E) ALICIA LAVIN, LUIS VALDES, FRANCISCO SANCHEZ, PABLO ABAUNZA Instituto Español de Oceanografía (IEO) ANDRE FOREST, JEAN BOUCHER, PASCAL LAZURE, ANNE-MARIE JEGOU Institut Français de Recherche pour l’Exploitation de la MER (IFREMER) Contents 1. Introduction 2. Geography of the Bay of Biscay 3. Hydrography 4. Biology of the Pelagic Ecosystem 5. Biology of Fishes and Main Fisheries 6. Changes and risks to the Bay of Biscay Marine Ecosystem 7. Concluding remarks Bibliography 1. Introduction The Bay of Biscay is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean, indenting the coast of W Europe from NW France (Offshore of Brittany) to NW Spain (Galicia). Tradition- ally the southern limit is considered to be Cape Ortegal in NW Spain, but in this contribution we follow the criterion of other authors (i.e. Sánchez and Olaso, 2004) that extends the southern limit up to Cape Finisterre, at 43∞ N latitude, in order to get a more consistent analysis of oceanographic, geomorphological and biological characteristics observed in the bay. The Bay of Biscay forms a fairly regular curve, broken on the French coast by the estuaries of the rivers (i.e. Loire and Gironde). The southeastern shore is straight and sandy whereas the Spanish coast is rugged and its northwest part is characterized by many large V-shaped coastal inlets (rias) (Evans and Prego, 2003). The area has been identified as a unit since Roman times, when it was called Sinus Aquitanicus, Sinus Cantabricus or Cantaber Oceanus. The coast has been inhabited since prehistoric times and nowadays the region supports an important population (Valdés and Lavín, 2002) with various noteworthy commercial and fishing ports (i.e. -

Spanish Residential Property Investment Opportunity

Spanish residential property investment opportunity Why Costa de la Luz? A specialist real estate advisory team focused on identifying, for our clients, property investment opportunities in golf developments along the Costa de la Luz Section I: General Overview of the Spanish Housing Market 2 Spanish House Prices remain affordable for northern European buyers Spanish house prices have risen significantly, yet they remain differences are more acute when compared to key Northern Europea affecting our business will be the purchasing power of foreigners ( Spain. Spanish average house price evolution 1987-2003 Average property price 3,000 2,000 Property price evolution in Spain compared to property prices é/m2 1,000 1987-2003 CAGR 10.1% Spanish house prices and0 GDP relative to the EU - 2002 Averag 140 1987 120 1988 cheap when compared to property prices across most of Northern Europe. 1989 100 1990 in particularn cities, Northern home to Europeans)our target market. who intend The tomost purchase important a property macroe along coa 80 1991 Finland 1992 60 Norway 1993 40 1994 Sweden 1995 20 1996 2001 GDP per capita - Relative to EU average Denmark Spain 0 1997 Sources: INE, UK land registry, HBOS, Department of 1998 40 60 80Greece 100 120 140 160 Européenne de l'Immobilier, Bulwein AG, Ministerio France 1999 3,000 Austria 2000 2001 Netherlands 2,000 Germany 2002 /m2 2003 € Ireland 1,000 in EU countries Italy € /m2- Relative to EU average UK 0 UK s in EU countries - 2002 Ireland Italy Economy, Switzerland, RICS, Statistics Norway, Sta Netherlands de Fomento, Titan research 4,000 Germany conomic factor 3,000 e property pricesAustri ofa European cities - 2002 /m2 France € 2,000 The Denmark 1,000 Norway stal Sweden 0 Greece Spain London Portugal Paris Finland Stockholm tistics Finland, Statistics Sweden, Denmarks Statis Amsterdam Dublin Frankfurt Madrid Barcelona Seville Malaga tik, Gunne, Confédération Valencia 3 Affordability According to the OECD, Spain is 14% cheaper than the EU 15 average. -

Airbnb Offer in Spain—Spatial Analysis of the Pattern and Determinants of Its Distribution

International Journal of Geo-Information Article Airbnb Offer in Spain—Spatial Analysis of the Pattern and Determinants of Its Distribution Czesław Adamiak 1,2,* , Barbara Szyda 1 , Anna Dubownik 1 and David García-Álvarez 3 1 Department of Spatial Planning and Tourism, Faculty of Earth Sciences, Nicolaus Copernicus University, 87-100 Toru´n,Poland; [email protected] (B.S.); [email protected] (A.D.) 2 Department of Geography, Faculty of Social Sciences, Umeå University, 901 87 Umeå, Sweden 3 Departamento de Análisis Geográfico Regional y Geografía Física, Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, University of Granada, 18072 Granada, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-56-611-2571 Received: 28 February 2019; Accepted: 15 March 2019; Published: 22 March 2019 Abstract: The rising number of homes and apartments rented out through Airbnb and similar peer-to-peer accommodation platforms cause concerns about the impact of such activity on the tourism sector and property market. To date, spatial analysis on peer-to-peer rental activity has been usually limited in scope to individual large cities. In this study, we take into account the whole territory of Spain, with special attention given to cities and regions with high tourist activity. We use a dataset of about 250 thousand Airbnb listings in Spain obtained from the Airbnb webpage, aggregate the numbers of these offers in 8124 municipalities and 79 tourist areas/sites, measure their concentration, spatial autocorrelation, and develop regression models to find the determinants of Airbnb rentals’ distribution. We conclude that apart from largest cities, Airbnb is active in holiday destinations of Spain, where it often serves as an intermediary for the rental of second or investment homes and apartments.