Arizona Corporation Commission's Response to Petition for Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JLBC Staff and Agency Directory Listings

APPROPRIATIONS COMMITTEE MEMBERS Fifty-fourth Legislature Second Regular Session SENATE HOUSE David Gowan, Chairman Regina Cobb, Chairman Vince Leach, Vice-Chairman John Kavanagh, Vice-Chairman Lela Alston Diego Espinoza Sean Bowie Charlene R. Fernandez Heather Carter John Fillmore Sine Kerr Randall Friese David Livingston Anthony Kern Lisa Otondo Aaron O. Lieberman Michelle Ugenti-Rita Bret Roberts Ben Toma Michelle Udall STAFF OF THE JOINT LEGISLATIVE BUDGET COMMITTEE • Director .......................................................................................................................... Richard Stavneak • Office Manager .............................................................................................................. Linda Monsanto • Deputy Directors ........................................................................................................... Stefan Shepherd ....................................................................................................................................... Jack Brown • Chief Economist ............................................................................................................. Hans Olofsson • Senior Consultant .......................................................................................................... Micaela Larkin • Principal Fiscal Analysts ................................................................................................. Patrick Moran ...................................................................................................................................... -

AZ Dept of Financial Institutions Performance Audit Report

A REPORT TO THE ARIZONA LEGISLATURE Performance Audit Division Performance Audit and Sunset Review Arizona Department of Financial Institutions August • 2013 REPORT NO. 13-05 Debra K. Davenport Auditor General The Auditor General is appointed by the Joint Legislative Audit Committee, a bipartisan committee composed of five senators and five representatives. Her mission is to provide independent and impartial information and specific recommendations to improve the opera- tions of state and local government entities. To this end, she provides financial audits and accounting services to the State and political subdivisions, investigates possible misuse of public monies, and conducts performance audits of school districts, state agencies, and the programs they administer. The Joint Legislative Audit Committee Senator Chester Crandell, Chair Representative John Allen, Vice Chair Senator Judy Burges Representative Paul Boyer Senator Rich Crandall Representative Andrea Dalessandro Senator Steve Gallardo Representative Martin Quezada Senator Katie Hobbs Representative Kelly Townsend Senator Andy Biggs (ex officio) Representative Andy Tobin (ex officio) Audit Staff Dale Chapman, Director ShanDot Reinhard Hays, Manager, Manager and and Contact Contact Person Person AnneDerek Hunter Barber, ,Team Team Leader Leader StevenCathy Clark Meyeroff Mike Devine Copies of the Auditor General’s reports are free. You may request them by contacting us at: Office of the Auditor General 2910 N. 44th Street, Suite 410 • Phoenix, AZ 85018 • (602) 553-0333 Additionally, many of our reports can be found in electronic format at: www.azauditor.gov STATE OF ARIZONA DEBRA K. DAVENPORT, CPA OFFICE OF THE MELANIE M. CHESNEY AUDITOR GENERAL DEPUTY AUDITOR GENERAL AUDITOR GENERAL August 29, 2013 Members of the Arizona Legislature The Honorable Janice K. -

STATE of ARIZONA OFFICIAL CANVASS 2014 General Election

Report Date/Time: 12/01/2014 07:31 AM STATE OF ARIZONA OFFICIAL CANVASS Page Number 1 2014 General Election - November 4, 2014 Compiled and Issued by the Arizona Secretary of State Apache Cochise Coconino Gila Graham Greenlee La Paz Maricopa Mohave Navajo Pima Pinal Santa Cruz Yavapai Yuma TOTAL Total Eligible Registration 46,181 68,612 70,719 29,472 17,541 4,382 9,061 1,935,729 117,597 56,725 498,657 158,340 22,669 123,301 76,977 3,235,963 Total Ballots Cast 21,324 37,218 37,734 16,161 7,395 1,996 3,575 877,187 47,756 27,943 274,449 72,628 9,674 75,326 27,305 1,537,671 Total Voter Turnout Percent 46.17 54.24 53.36 54.84 42.16 45.55 39.45 45.32 40.61 49.26 55.04 45.87 42.68 61.09 35.47 47.52 PRECINCTS 45 49 71 39 22 8 11 724 73 61 248 102 24 45 44 1,566 U.S. REPRESENTATIVE IN CONGRESS - DISTRICT NO. 1 (DEM) Ann Kirkpatrick * 15,539 --- 23,035 3,165 2,367 925 --- 121 93 13,989 15,330 17,959 --- 4,868 --- 97,391 (REP) Andy Tobin 5,242 --- 13,561 2,357 4,748 960 --- 28 51 13,041 20,837 21,390 --- 5,508 --- 87,723 U.S. REPRESENTATIVE IN CONGRESS - DISTRICT NO. 2 (DEM) Ron Barber --- 14,682 --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- 94,861 --- --- --- --- 109,543 (NONE) Sampson U. Ramirez (Write-In) --- 2 --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- 54 --- --- --- --- 56 (REP) Sydney Dudikoff (Write-In) --- 5 --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- 43 --- --- --- --- 48 (REP) Martha McSally * --- 21,732 --- --- --- --- --- --- --- --- 87,972 --- --- --- --- 109,704 U.S. -

ARIZONA CORPORATION COMMISSION * > Q.1 August 21, 2018

ORIGINAL II II II II III III IlIIIIIII al .. o 0000191428 cQMMlssloneR§ $7 ~ 'We'x. c¢8iJIKniséT6rIéR TOM FORESE - Chairman g 8 BOB BURNS r ANDY TOBIN 5 Direct Line: (602) 542-3625 7> 4° BOYD w. DUNN *», ,.4> Email: [email protected] JUSTIN OLSON ARIZONA CORPORATION COMMISSION * > q.1 August 21, 2018 ,... r e " LX) C) c'> co O ..::o >U Docket Control Arizona Corporation Commission r=1-G13 4...) ..-l(..>r@@~; Arizona Corporation Commission r o i DOCKETED -» 1200 W Washington St. i c:> jg_~-_ v *iv f""l Phoenix, AZ 85007 > --l"".C3 AUG21 2018 w e UP : <9 i RE: WS-02987A-18-0050 . ,_ (..1 i nocxsnsnv . 4 i _.J My Fellow Commissioners: i I want to emphasize my appreciation for the Town of Queen Creek and Utilities Division Staff in their recent requests for administrative subpoenas in the above-captioned matter. In light of the recent events in this and related Dockets, I feel deeply that Johnson Utilities' track record for delay and blatant contumacy for the Commission's authority I i should no longer be allowed to prevent the Commission from taking action on its executive and judicial duties. The history of Johnson Utilities has consistently been that of delay and obstructionism, unscrupulous litigation, and wanton disrespect, and now we are looking at potentially life-threatening conditions to the public, employees, and first responders while our interim manager agreement is suspended for an indefinite period of time. The critical health and safety crises ECOR advised us of last week go to the heart of why urgency and compliance were so imperative for the Commission from the outset. -

Limmiimiuiii RECEIVED a O *

lg }u . o COR P04) I K 4 9 . r '\, / V . .4 x v . \ . l . e Q, ` . in.) . ` q l!ll\\liw\illIllII I1\ \4H\HIH1 . Ar mIv <8§ lIMMIIMIUIII RECEIVED A O *.. 4° A2 CORP COHHISSIOH )b3 n|1Ar* é opus * <9 DOCKET CONTROL ~*l~1912°" Zen ApR 2`l p I: 05 Memorandum From the office of Commissioner Andy Tobin Arizona Corporation Commission 3 1200 w. WASHINGTON I PHOENIX, ARIZONA (602) 542-3625 Arizona Computation Commission DOCKETED TO: Docket Control APR 2 7 2017 DATE: April 27"', 2017 Docxmn Y FROM: Commissioner Andy Tobin's Office SUBJECT: Navajo Generating Station E-00000C-17-0039 Following is correspondence from Commissioner Tobin's office. CERTIFICATION OF SERVICE On this 27th day of April, 2017, the foregoing document was filed with Docket Control as a correspondence from Commissioner Andy Tobin, and copies of the foregoing were mailed on behalf of Commissioner Andy Tobin to the following who have not consented to email service. On this date or as soon as possible thereafter, the Commission's eDocket program will automatically email a link to the foregoing to the following who have consented to email service. /. By: I nm r(tl 1nor Assl t tt 0Andy bin Timothy LaSota Arizona Corporation Commission 1200 W. Washington Street Phoenix, Arizona 85007 Elijah Abinah Arizona Corporation Commission 1200 W. Washington Street Phoenix, Arizona 85007 2115££»,Vu COMMI I NER ANDY TOBIN TOM FORESE - Chairman | 54*) COMMISSIONER BOB BURNS *off"i '5 '/ 3 DOUG LITTLE Direct Line: (602)542-8625 ANDY TOBIN Email: [email protected] BOYDw. -

Municipal 2012

2012 Municipal policy Statement Core Principles • PROTECTION OF SHARED REVENUES. Arizona’s municipalities rely on the existing state-collected shared revenue system to provide quality services to their residents. The League will resist any attacks on this critical source of funding for localities, which are responsibly managing lean budgets during difficult economic times. The League opposes unfunded legislative mandates, as well as the imposition of fees and assessments on municipalities as a means of shifting the costs of State operations onto cities and towns. In particular, the League opposes any further diversions of Highway User Revenue Fund (HURF) monies away from municipalities and calls upon the Legislature to restore diverted HURF funding to critical road and street projects. • PRESERVATION OF LOCAL CONTROL. The League calls upon the Arizona Legislature to respect the authority of cities and towns to govern their communities free from legislative interference and the imposi- tion of regulatory burdens. The League shares the sentiments of Governor Brewer, who, in vetoing anti-city legislation last session, wrote: “I am becoming increasingly concerned that many bills introduced this session micromanage decisions best made at the local level. What happened to the conservative belief that the most effective, responsible and responsive government is government closest to the people?” Fiscal Stewardship The League is prepared to support reasonable reforms to the state revenue system that adhere to the principles of simplicity, fairness and balance and that do not infringe upon the ability of cities and towns to implement tax systems that reflect local priorities and economies. • The League proposes to work with the Legislature to ensure that both the State and municipalities are equipped with the economic development tools they need to help them remain competitive nationally and internationally. -

Download 2014 Summaries As a High Resolution

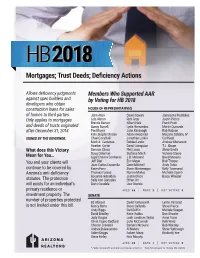

HB2018 Mortgages; Trust Deeds; Deficiency Actions Allows deficiency judgments Members Who Supported AAR against spec builders and by Voting for HB 2018 developers who obtain HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES construction loans for sales of homes to third parties. John Allen David Gowan Jamescita Peshlakai Only applies to mortgages Lela Alston Rick Gray Justin Pierce Brenda Barton Albert Hale Frank Pratt and deeds of trusts originated Sonny Borrelli Lydia Hernandez Martin Quezada after December 31, 2014. Paul Boyer John Kavanagh Bob Robson Kate Brophy McGee Adam Kwasman Macario Saldate, IV SIGNED BY THE GOVERNOR. Chad Campbell Jonathan Larkin Carl Seel Mark A. Cardenas Debbie Lesko Andrew Sherwood Heather Carter David Livingston T.J. Shope What does this Victory Demion Clinco Phil Lovas Steve Smith Doug Coleman Stefanie Mach Victoria Steele Mean for You… Lupe Chavira Contreras J.D. Mesnard David Stevens You and your clients will Jeff Dial Eric Meyer Bob Thorpe Juan Carlos Escamilla Darin Mitchell Andy Tobin continue to be covered by Karen Fann Steve Montenegro Kelly Townsend Arizona’s anti-deficiency Thomas Forese Norma Muñoz Michelle Ugenti Rosanna Gabaldón Justin Olson Bruce Wheeler statutes. The protection Sally Ann Gonzales Ethan Orr will exists for an individual’s Doris Goodale Lisa Otondo primary residence or AYES: 55 | NAYS: 2 | NOT VOTING: 3 investment property. The SENATE number of properties protected Ed Ableser David Farnsworth Lynne Pancrazi is not limited under this bill. Nancy Barto Steve Gallardo Steve Pierce Andy Biggs Gail Griffin Michele Reagan David Bradley Katie Hobbs Don Shooter Judy Burges Leah Landrum Taylor Anna Tovar Olivia Cajero Bedford John McComish Kelli Ward Chester Crandell Barbara McGuire Bob Worsley Andrea Dalessandro Al Melvin Steve Yarbrough Adam Driggs Robert Meza Kimberly Yee Steve Farley Rick Murphy AYES: 29 | NAYS: 1 | NOT VOTING: 0 * Eddie Farnsworth and Warren Petersen voted no – they did not want to change the statute. -

2020 Election Preview a Pandemic of Electoral Chaos Arizona Association of Health Underwriters Prepared by Dr

2020 Election Preview A Pandemic of Electoral Chaos Arizona Association of Health Underwriters Prepared by Dr. Marcus Osborn and Dan Romm Kutak Rock, LLP Arizona 2020 Key Election Dates Early Register to Request Last Day to Election Day Voting Vote an Early Mail Ballot Begins Deadline Ballot Deadline 2 Arizona 2020 Ballot Propositions “Pot and Schools Go together like Peas and Carrots” 3 Proposition 207 – Smart and Safe Arizona Act Proposition 207 would legalize recreational marijuana use in Arizona for people ages 21 and over. Under the proposal, purchases would be charged the regular sales tax plus an additional 16 percent, which would fund the government’s cost of administering the program. Any money left over will be allocated to community colleges, infrastructure, roads and highways, public safety and public health. This measure allows people who have been arrested or convicted of some marijuana offenses, such as possessing, consuming or transporting 2.5 ounces or less, to petition to have their records expunged. Additionally, this proposal clarifies that people can be charged with driving under the influence of marijuana. 4 Proposition 208 – Invest in Education Act Backed by the state’s teacher’s union, Proposition 208 calls for a 3.5 percent tax surcharge on income above $250,000 for an individual or above $500,000 for couples. This initiative hopes to raise about $940 million a year for schools. Under this ballot proposal, half of the new tax generated would be devoted to raises for credentialed teachers, 25 percent would go to increasing the wages for cafeteria workers, bus drivers and other support staff, and the remaining amount would be allocated for teacher training, vocational education and other initiatives. -

July 1, 2020 the Honorable Doug Ducey Governor, State Of

July 1, 2020 The Honorable Doug Ducey Governor, State of Arizona 1700 West Washington Street Phoenix, AZ 85007 Dear Governor Ducey: In August 2017, after the deadly white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, the Arizona Preservation Foundation requested that the Arizona Historical Advisory Commission (AHAC) meet to review, discuss, and recommend to the proper authorities the removal of Confederate memorials on Arizona public land or those maintained by public funding. State Representative Reginald Bolding and several Arizona civil rights organizations also called upon your Administration and the State Legislature to support their removal. Unfortunately, nothing was done. Three years later, after yet another senseless killing of an African-American and the subsequent nationwide demonstrations seeking the elimination of systemic racism and bigotry, the Foundation created a sign-on letter for Arizona individuals and organizations to add their names, now in excess of 300, in support of the removal of the following Confederate memorials from Arizona public property: • Monument to Arizona Confederate Troops, Wesley Bolin Plaza, Phoenix • Confederate Monument, Historical Soldiers Monument Cemetery area of the state- owned Southern Arizona Veterans' Cemetery, Sierra Vista • Jefferson Davis monument highway marker, U.S. Route 60, east of Phoenix • Battle of Picacho Pass monument, Picacho Peak State Park, Pinal County The removal of these monuments will not “change” history or “erase” it. What does change with such removals is what Arizona decides is worthy of civic honor and recognition. As historians, Arizonans, and Americans, we have an obligation to confront the complex and often difficult stories of our past. We fully recognize the multitude of ways that our understanding and characterization of our shared story continues to shape our collective future. -

Before the Arizona Corporation Commission

IN THE SUPREME COURT STATE OF ARIZONA JOHNSON UTILITIES, LLC, an Arizona Arizona Supreme Court Limited Liability Company, Case No. CV-19-0105-PR Petitioner/Appellant, Court of Appeals, Division One v. Case No. 1 CA-CV 18-0197 ARIZONA CORPORATION Arizona Corporation Commission COMMISSION; and TOM FORESE, Docket No. WS-02987A-18-0050 BOB BURNS, ANDY TOBIN, BOYD W. DUNN and JUSTIN OLSON, in their official capacities as members of the Arizona Corporation Commission, Respondents/Appellees. RESPONDENTS/APPELLEES ARIZONA CORPORATION COMMISSION ET AL.’S SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF Robin R. Mitchell (No. 019213) Naomi E. Davis (No. 029863) Wesley C. Van Cleve (No. 020046) Arizona Corporation Commission 1200 W. Washington Street Phoenix, Arizona 85007 602.542.3402 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Attorneys for: Arizona Corporation Commission; and Tom Forese, Bob Burns, Andy Tobin, Boyd W. Dunn And Justin Olson, in their official capacities as members of the Arizona Corporation Commission TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................... 1 II. THE CONCURRENT OR PERMISSIVE CONSTITUTIONAL AUTHORITY OF ARTICLE 15, SECTION 3 OF THE ARIZONA CONSTITUTION PERMITS THE APPOINTMENT OF AN INTERIM MANAGER ...................................................................... 3 III. THE COMMISSION’S APPOINTMENT OF AN INTERIM MANAGER IS ALSO CONSISTENT WITH ITS RATEMAKING AUTHORITY UNDER ARTICLE 15, SECTION 3 .......... 7 IV. THE MANAGEMENT INTERFERENCE DOCTRINE DOES NOT ACT AS A BAR TO THE COMMISSION’S AUTHORITY TO ACT TO APPOINT AN INTERIM MANAGER FOR JOHNSON ....... 10 V. THE INTERIM MANAGER REMEDY LONG PRE-DATES JOHNSON UTILITIES ................................................................................. 12 VI. REVERSAL OF THE COURT OF APPEALS’ OPINION WOULD HAVE A FAR-REACHING IMPACT ON THE COMMISSION’S ABILITY TO EFFECTIVELY REGULATE PUBLIC SERVICE CORPORATIONS ................................ -

Beyond the Beltway a Report on State Energy and Climate Policies

POLICY BRIEF FEBRUARY 2018 BEYOND THE BELTWAY A REPORT ON STATE ENERGY AND CLIMATE POLICIES Daniel A. Farber Beyond the Beltway: A Report on State Energy and Climate Policies Summary Federal policy receives the bulk of the nation’s attention to energy and climate matters, from President Obama’s Clean Power Plan to President Trump’s withdrawal from the Paris Agreement. Yet much of our nation’s energy and climate policy is made by governors, state legislatures and agencies across the country. However, it can be very difficult to track these disparate actions to understand where progress is being made and which states are falling behind. Beyond the Beltway provides insight into the range of factors – political, geographical, economic and more – that determine the immensely varied state energy and climate policies across the nation. About this Report This Report is a compilation of a series of Legal Planet blog posts written in late 2017 and early 2018. Legal Planet is a collaborative effort of the UC Berkeley and UCLA Schools of Law and is accessible at www.legal-planet.org. The original posts were compiled here and edited for consistency. About the Author Daniel A. Farber is the Sho Sato Professor of Law and Co-Faculty Director of the Center for Law, Energy & the Environment at the University of California, Berkeley, School of Law. He is an internationally recognized environmental law and constitutional law expert. He would like to thank Erica Sun and Alyssa Wu for their research assistance and Ted Lamm for his invaluable editing and feedback. Cover photo credits (l-r): Flickr’s Warren Rohner, s pants and BFS Man. -

Arizona State Endorsed Candidates 2012

Arizona State Endorsed Candidates 2012 State Constitutional Offices Arizona House of Representatives No Races HD1- Prescott Valley, Andy Tobin HD1- Prescott, Karen Fann HD7- St Michael, Albert Hale United States Senate HD8- Casa Grande, Frank Pratt HD12- Gilbert, Eddie Farnsworth Jeff Flake HD13- Litchfield Park, Steve Montenegro HD14- Sierra Vista, David Gowan United States House of HD14- Sierra Vista, David Stevens HD15- Cave Creek, Heather Carter Representatives HD15- Scottsdale, John Allen HD17- Chandler, Tom Forese, CD1- Ann Kirkpatrick HD17- Chandler, J.D. Mesnard CD2- Ron Barber HD18- Chandler,Bob Robson CD3- Raul Grijalva HD18- Chandler, Jeff Dial CD4- Paul Gosar HD20- Phoenix, Paul Boyer CD5- Matt Salmon HD20- Phoenix, Jackie Trasher CD6- David Schweikert HD21- Sun City, Rick Gray CD7- Ed Pastor HD21- Glendale, Debbie Lesko CD8- Trent Franks HD23- Fountain Hills, John Kavanagh CD9- Kyrsten Sinema HD23- Scottsdale, Michelle Ugenti HD24- Phoenix, Chad Campbell HD24- Phoenix, Lela Alston Arizona Senate HD25- Mesa, Justin Olson SD01- Prescott, Steve Pierce HD25- Mesa, Justin Pierce SD02- Tucson, Linda Lopez HD27- Phoenix, Ruben Gallego SD03- Tucson, Olivia Cajero Bedford HD30- Phoenix, Debbie McCune Davis SD04- Yuma, Lynne Pancrazi SD10- Tucson, Frank Antenori SD12- Gilbert, Andy Biggs SD15- Phoenix, Nancy Barto Corporation Commission SD17- Chandler, Steve Yarbrough SD18- Phoenix, John McComish STATEWIDE SD19- Phoenix, Anna Tovar No Position SD20- Phoenix, Kimberly Yee SD21- Peoria, Rick Murphy SD22- Sun City West, Judy Burges SD23- Scottsdale, Michelle Reagan SD24- Phoenix, Katie Hobbs Information on SD27- Phoenix, Leah Landrum SD28- Phoenix, Adam Driggs VOTER VIEW? VOTER REGISTRATION SD29- Phoenix, Steve Gallardo SEARCH YOUR EARLY BALLOT OR SD30- Phoenix, Robert Meza DROP OFF LOCATION? NOVEMBER 6th POLLING INFO? Ballot Initiatives STATEWIDE Find it Here: https://voter.azsos.gov/ NO Positions .