Sexual/Textual Tendencies in Shyam Selvadurai's Funny

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indigenizing Sexuality and National Citizenship: Shyam Selvadurai's

Indigenizing Sexuality and National Citizenship: Shyam Selvadurai’s Cinnamon Gardens Heather Smyth The intersection of feminist and postcolonial critique has enabled us to understand some of the co-implications of gendering, sexuality, and postcolonial nation building. Anne McClintock, for instance, argues that nations “are historical practices through which social difference is both invented and performed” and that “nations have historically amounted to the sanctioned institutionalization of gender difference” (89; italics in original). Women’s reproduction is put to service for the nation in both concrete and symbolic ways: women reproduce ethnicity biologically (by bearing children) and symbolically (by representing core cultural values), and the injunction to women to reproduce within the norms of marriage and ethnic identification, or heterosexual endogamy, makes women also “reproducers of the boundaries of ethnic/national groups” (Yuval-Davis and Anthias 8–9; emphasis added). National identity may be routed through gender, sexuality, and class, such that “respectability” and bourgeois norms, including heterosexuality, are seen as essential to nationalism, perhaps most notably in nations seeking in- dependence from colonial power (Mosse; de Mel). Shyam Selvadurai’s historical novel Cinnamon Gardens, set in 1927–28 Ceylon, is a valuable contribution to the study of gender and sexuality in national discourses, for it explores in nuanced ways the roots of gender norms and policed sexuality in nation building. Cinnamon Gardens indigenizes Ceylonese/ Sri Lankan homosexuality not by invoking the available rich history of precolonial alternative sexualities in South Asia, but rather by tying sexuality to the novel’s other themes of nationalism, ethnic conflict, and women’s emancipation. -

Indi@Logs Vol 8 2021, Pp 11-28, ISSN: 2339-8523

Indi@logs Vol 8 2021, pp 11-28, ISSN: 2339-8523 https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/indialogs.178 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- “IS GANDHI THE HERO?”: A REAPPRAISAL OF GANDHI’S VIEWS ABOUT WOMEN IN DEEPA MEHTA’S WATER PILAR SOMACARRERA-ÍÑIGO Universidad Autónoma de Madrid [email protected] Received: 26-11-2020 Accepted: 31-01-2021 ABSTRACT Set in 1938 against the backdrop of India’s anti-colonial movement led by Gandhi, the film Water (2005) by Deepa Mehta crudely exposes one of the most demeaning aspects of the patriarchal ideology of Hinduism: the custom of condemning widows to a life of self-denial and deprivation at the ashrams. Mehta has remarked that figures like Gandhi have inspired people throughout the ages. Nonetheless, in this essay I argue that under an apparent admiration for the figure of Gandhi in the context of the emancipation of India in general and widows in particular, Water questions whether Gandhi’s doctrines about the liberation of women were effective or whether, on the contrary, they contributed to restricting women to the private realm by turning them into personifications of the Indian nation. In this context of submission and oppression of women in India, Gandhi did try to improve their conditions though he was convinced that gender is destiny and that women’s chastity is connected to India’s national honour. I argue that Mehta’s film undermines Gandhi’s idealism by presenting images of him and dialogues in which he is the topic. As a methodological approach, I propose a dialogic (Bahktin 1981) reading of the filmic text which analyses how a polyphony of voices praise and disparage the figure of Gandhi in Water. -

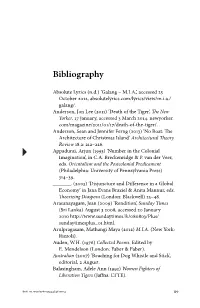

Bibliography

Bibliography Absolute Lyrics (n.d.) ‘Galang – M.I.A.’, accessed 25 October 2012, absolutelyrics.com/lyrics/view/m.i.a./ galang/. Anderson, Jon Lee (2011) ‘Death of the Tiger’, The New Yorker, 17 January, accessed 3 March 2014. newyorker. com/magazine/2011/01/17/death-of-the-tiger/. Anderson, Sean and Jennifer Ferng (2013) ‘No Boat: The Architecture of Christmas Island’ Architectural Theory Review 18.2: 212–226. Appadurai, Arjun (1993) ‘Number in the Colonial Imagination’, in C.A. Breckenridge & P. van der Veer, eds. Orientalism and the Postcolonial Predicament (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press) 314–39. _______. (2003) ‘Disjuncture and Difference in a Global Economy’ in Jana Evans Braziel & Anita Mannur, eds. Theorizing Diaspora (London: Blackwell) 25–48. Arasanayagam, Jean (2009) ‘Rendition’, Sunday Times (Sri Lanka) August 3 2008, accessed 20 January 2010 http://www.sundaytimes.lk/080803/Plus/ sundaytimesplus_01.html. Arulpragasam, Mathangi Maya (2012) M.I.A. (New York: Rizzoli). Auden, W.H. (1976) Collected Poems. Edited by E. Mendelson (London: Faber & Faber). Australian (2007) ‘Reaching for Dog Whistle and Stick’, editorial, 2 August. Balasingham, Adele Ann (1993) Women Fighters of Liberation Tigers (Jaffna: LTTE). DOI: 10.1057/9781137444646.0014 Bibliography Balint, Ruth (2005) Troubled Waters (Sydney: Allen & Unwin). Bastians, Dharisha (2015) ‘In Gesture to Tamils, Sri Lanka Replaces Provincial Leader’, New York Times, 15 January, http://www. nytimes.com/2015/01/16/world/asia/new-sri-lankan-leader- replaces-governor-of-tamil-stronghold.html?smprod=nytcore- ipad&smid=nytcore-ipad-share&_r=0. Bavinck, Ben (2011) Of Tamils and Tigers: A Journey Through Sri Lanka’s War Years (Colombo: Vijita Yapa and Rajini Thiranagama Memorial Committee). -

Shyam Selvadurai: Multiple Identities

MASARYK UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF EDUCATION DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE Shyam Selvadurai: Multiple identities Bachelor thesis Brno 2015 Superviser: PhDr. Irena Přibylová, Ph.D. Written by: Kateřina Halfarová Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem závěrečnou bakalářskou práci vypracovala samostatně, s využitím pouze citovaných literárních pramenů, dalších informací a zdrojů v souladu s Disciplinárním řádem pro studenty Pedagogické fakulty Masarykovy univerzity a se zákonem č. 121/2000 Sb., o právu autorském, o právech souvisejících s právem autorským a o změně některých zákonů (autorský zákon), ve znění pozdějších předpisů. ………………………… Kateřina Halfarová 2 Acknowledgment I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor PhDr. Irena Přibylová, Ph.D. for her inspiration, support, valuable advice, and time she devoted to me. I am very thankful for her guidance that helped me finish my thesis. 3 Anotace Bakalářská práce „Shyam Selvadurai: multiple identities“ se zabývá vlivem střetu kultur na hlavní hrdiny knihy Swimming in the Monsoon Sea napsanou Shyamem Selvaduraiem. Hlavním cílem práce je zjistit, zda a eventuálně jak, střet kultur ovlivňuje vývoj hrdinů knihy v jejich dospívajícím věku. Zda má multikulturalismus dopad na změnu stávající identity. Teoretická část práce se věnuje popisem multikulturalismu jako celku, multikulturní literatuře se zaměřením na autory pocházející z jižní Asie, protože autor rozebírané knihy pochází ze Srí Lanky. Další kapitoly jsou věnovány přímo autorovi Shyamu Selvadurai a jeho knize Swimming in the Monsoon Sea. Praktická část bakalářské práce analyzuje román a zaměřuje se na vývoj hrdinů v důsledku střetu kultur v oblasti rodiny, školy, náboženství, kultury, jazyka a osobního života. Klíčová slova Multikulturalismus; identita; literatura pro dospívající čtenáře; Shyam Selvadurai; střet kultur; Swimming in the Monsoon Sea. -

The Nation and Its Discontents South Asian Literary Association 2014 Annual Conference Program JANUARY 8-9, 2014

The Nation and Its Discontents South Asian Literary Association 2014 Annual Conference Program JANUARY 8-9, 2014 ALOFT HOTEL (CITY CENTER) 515 NORTH CLARK STREET; CHICAGO, IL 60654 312-661-1000 TUESDAY, JANUARY 7 PRE-CONFERENCE MEETING - “THE YELLOW LINE” ROOM 6-8 p.m. Executive Committee DAY 1: WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 8 8:00 a.m. onward REGISTRATION Lobby 9:00-9:30 a.m. CONFERENCE WELCOME ROOM: THE L Moumin Quazi, Tarleton State University SALA President OPENING: Madhurima Chakraborty, Columbia College Chicago Umme Al-wazedi, Augustana College Conference Co-Chairs 1 9:45-11:00 a.m. SESSION 1 (PANELS 1A, 1B, AND 1C) 1A: INTERROGATING INDEPENDENCE AND NATIONALISM ROOM: THE RED LINE Panel Chair: Henry Schwarz, Georgetown University 1. Nationalism and Gender in Cracking India Anil H. Chandiramani, University of Minnesota, Twin Cities 2. Fragments of History and Female Silence: Discursive Interventions in Partition Narratives Parvinder Mehta, Siena Heights University 3. Engendering Nationalism: From Swadeshi to Satyagraha Indrani Mitra, Mount St. Mary's University 4. Unhomed and Deterritorialized: Quest for National Identity in Indira Goswami's Ahiran Kumar Sankar Bhattacharya, Birla Institute of Technology and Sciences (BITS), Pilani 1B: EUROPE IMAGINES SOUTH ASIA ROOM: THE BLUE LINE Panel Chair: J. Edward Mallot, Arizona State University 1. From Somebodies to Nobodies: The Dilemma of National Belonging for Poor Whites in India and Britain Suchismita Banerjee, University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee 2. White Elephants and Discontents Moumin Quazi, Tarleton State University 3. Social Outcasts in Melodrama: Cross-Cultural Comparisons between Indian and Spanish Melodrama in Film Maria Dolores Garcia-Borron, Independent scholar 4. -

Diaspora, Law and Literature Law & Literature

Diaspora, Law and Literature Law & Literature Edited by Daniela Carpi and Klaus Stierstorfer Volume 12 Diaspora, Law and Literature Edited by Daniela Carpi and Klaus Stierstorfer An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 License, as of February 23, 2017. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. ISBN 978-3-11-048541-7 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-048925-5 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-048821-0 ISSN 2191-8457 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Printing: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com TableofContents DanielaCarpi Foreword VII Klaus Stierstorfer Introduction: Exploringthe InterfaceofDiaspora, Law and Literature 1 Pier Giuseppe Monateri Diaspora, the West and the Law The Birth of Christian Literaturethrough the LettersofPaul as the End of Diaspora 7 Riccardo Baldissone -

In Romesh Gunesekera's Ghost Country

Commonwealth Essays and Studies 40.2 | 2018 Confluence/Reconstruction In Romesh Gunesekera’s Ghost Country Pascal Zinck Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ces/296 DOI: 10.4000/ces.296 ISSN: 2534-6695 Publisher SEPC (Société d’études des pays du Commonwealth) Printed version Date of publication: 1 April 2018 Number of pages: 85-96 ISSN: 2270-0633 Electronic reference Pascal Zinck, “In Romesh Gunesekera’s Ghost Country”, Commonwealth Essays and Studies [Online], 40.2 | 2018, Online since 05 November 2019, connection on 02 April 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/ces/296 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ces.296 Commonwealth Essays and Studies is licensed under a Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. In Romesh Gunesekera’s Ghost Country The French term “reconstruction” has two different meanings, both of which are in common usage. Its older meaning refers to the physical act of rebuilding what has been damaged or destroyed, as a like-for-like replacement. A more modern meaning suggests a more structural and systematic process. The present paper posits that understanding the dif- ferences between the two is helpful in post-conflict resolution and reconciliation. To provide a long-term approach to fractures and vulnerabilities, a nation must not only open a Pandora’s box of legal accountability. Reconstruction ultimately poses the challenge of redefining national iden- tity. Romesh Gunesekera’s Noontide Toll explores such issues in the context of the three decade- long civil war between the Government of Sri Lanka and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Elam (LTTE). -

A Critical Study of Shyam Selvadurai's Funny Boy And

International Journal of Management (IJM) Volume 11, Issue 7, July 2020, pp. 1488-1493, Article ID: IJM_11_07_133 Available online at http://iaeme.com/Home/issue/IJM?Volume=11&Issue=7 ISSN Print: 0976-6502 and ISSN Online: 0976-6510 DOI: 10.34218/IJM.11.7.2020.133 © IAEME Publication Scopus Indexed MANAGING GENDER (ED) IDENTITY: A CRITICAL STUDY OF SHYAM SELVADURAI’S FUNNY BOY AND BUCHI EMECHETA’S SECOND CLASS CITIZEN Puja Sarmah M.Phil. Research Scholar, Dibrugarh University, Assam, India ABSTRACT Shyam Selvadurai’s novel Funny Boy and Buchi Emecheta’s novel Second Class Citizen are considered as the groundbreaking works of postcolonial literature where the protagonist’s quest for identity in their prevalent society is clearly depicted. The word ‘funny’ itself in the title of the novel Funny Boy shows that living a queer life is considered as funny in the context of Indian society and how language dominating public and textual discourses is rendered funny and the word ‘second-class’ denotes the class in which the women, specially the black women are put in the society. Thus this paper aims to explore the identity crisis faced by the two protagonists, Ajrie, from the novel, Funny Boy and Adah, from the novel, Second Class Citizen. By exploring the interconnections between queer adolescence, gendered identity and postcolonialism, this paper attempts to study the neat narratives of postcolonial modernity to suggest the reorientation of South Asian and African fiction as a crucial outcome of the crossings. Key words: Gender, body, homosexuality, black, identity, LGBTQ Cite this Article: Puja Sarmah, Managing Gender(Ed) Identity: A Critical Study of , International Journal of Management, 11(7), 2020, pp. -

2015 Tamil Studies Symposium at York University

TAMIL STUDIES SYMPOSIUM at YORK UNIVERSITY Friday, 1 May 2015 10 am to 12:00 pm| Room 280A, Second Floor, York Lanes | York University Mental Health and Our Tamil Youth Bramilee Dhayanandhan (York University/CAMH) Trauma and Solidarity Between Indigenous and Tamil Youth Jesse Thistle (York University, University of Waterloo, Researcher for First Story) Hyphenated Self: My Identity ‘Unveiled’ post 9/11, post 2009 Fathima Nizamdeen (University of Toronto) Outside the Queer Mainstream N. Gitanjali Lena (LGBT Youth Line) Moderator: Vasuki Shanmuganathan (University of Toronto) Beyond Refuge: Shaping Tamil Studies in the Present 12:30 to 6:30 pm| Room 519, Fifth Floor, Kaneff Tower | York University 12:30 to 1:00 Welcome 1:00 to 2:30 Complicating Tamil‐ness at Home and in Diaspora Moderator: R. Cheran (University of Windsor) Caught Between Rebels and Armies: Competing Nationalisms and Anti‐Muslim Violence in Sri Lanka Amarnath Amarasingham (Dalhousie University) and Shobana Xavier (Wilfrid Laurier University) Invisible Diasporas: Can the Non‐Anglophone Diasporas Speak? Sinthujan Varatharajah (University College London) Sāyavēr Red and Slavery in Jaffna: A Social History of Commodity, Caste and Colonialism Mark Balmforth (Columbia University) Men and Ghosts: Reading Shyam Selvadurai’s The Hungry Ghosts as Truth Claim Arun Nedra Rodrigo (York University) 2:30 to 4:00 The Ocean Lady, The MV Sunsea and the Shrinking Rights of Tamil Asylum Seekers in Canada Moderator: Jennifer Hyndman (York University) Don't rock the boat: discourses on the arrival of Tamil refugees to Canada by boat Harini Sivalingam (York University) Tamil Boat People: Bars and Barriers to Asylum in Comparative Context Sharry Aiken (Queen’s University) People Smuggling and the Erosion of the Right to Seek Asylum in Canada: Appulonappa et al v. -

Downloads/Wiveca S.Pdf>

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sussex Research Online Excerpt from WRITING SRI LANKA LITERATURE, RESISTANCE AND THE POLITICS OF PLACE MINOLI SALGADO (ROUTLEDGE 2007) PART I pp. 9-38 1 Literature and Territoriality: Boundary Marking as a Critical Paradigm Etymologically unsettled, ‘territory’ derives from both terra (earth) and terrēre (to frighten) whence territorium, ‘a place from which people are frightened off’. Homi K. Bhabha, The Location of Culturei Sri Lankan literature in English constitutes an emergent canon of writing that has yet to find settlement in the field of postcolonial studies. ii It occupies an uncertain territory, which, in recent years, has itself been marked by the competing ethnic nationalisms of civil war and of contestatory constructions of home and belonging. The upsurge of literary production in English in the last thirty years has corresponded with the dynamic growth of postcolonial studies from the metropolitan centre, the international acclaim granted to writers such as Michael Ondaatje and Romesh Gunesekera, and, as significantly, with a period of heightened political unrest in Sri Lanka - a context of production and reception that is shaped by a politics of affiliation and competing claims to cultural authority. It is worth reminding ourselves that unlike most postcolonial nations, Sri Lanka’s national consciousness developed significantly after Independence and did so along communal lines.iii The 1950s witnessed the dramatic decline of Ceylonese or multi-ethnic Sri Lankan nationalism in favour of Sinhala linguistic nationalism along with the sharpening of Sri Lankan Tamil nationalismiv – a combination that culminated in the communal violence of 1983 and the start of the military conflict. -

Because Most People Marry Their Own Kind: a Reading of Selvadurai

Because Most People Marry Their Own Kind: A Reading of Shyam Selvadurai's uTunny Boy" R. RAJ RAO JT\ NEW PHASE has begun in writing from the Indian subconti• nent with the emergence of the Sri Lankan novelist Romesh Gunesekera, whose novel Reef ( 1994) was recently on the Booker Prize shortlist. Gunesekera describes Reef as a story of a society in transition and as a narrative that "illuminated the political, moral and emotional realities we all live by, whatever our circumstances and our obsessions" (Literature Matters 3). Less well-known than Gunesekera is another contemporary novelist from Sri Lanka, Shyam Selvadurai, whose first novel, Funny Boy ( 1994), was pub• lished in 1994 by Jonathan Cape, and reprinted by Penguin Books in India. Selvadurai, born in Colombo in 1965, left Sri Lanka after the 1983 riots in Colombo and settled with his family in Toronto, Canada. The year 1983 marks the beginning of the secessionist struggle in the island, in which the Tamils, mostly Hindu by faith, wanted to break away from the Sinhalese majority (mostly Buddhist), and form their own homeland in the north, in and around the province of Jaffna. I propose to look at Funny Boy, a novel with a Sri Lankan boy as its protagonist, against this political backdrop, from the angles of race, sexuality, and gender, and to show that a subaltern identi• fication exists between minorities in the three groups, who con• stitute the "other" of the male fanatical self. What I mean is this: in each of the domains of race, sexuality, and gender, there are those who are empowered and those who are not; I use "male- ness" and the chauvinism associated with it as a metaphor to incorporate the other two categories of race and sexuality (thereby hinting at a fusion), and I invent the phrase "male fanatical self to explore the notion of the self as empowered, the ARIEL: A Review of International English Literature, 28:1, January 1997 118 R. -

July / August 2017 Discussion Guide

JULY / AUGUST 2017 BOOK CLUB DISCUSSION GUIDE DISCUSSION GUIDE FUNNY BOY BY SHYAM SELVADURAI CHRISTOPHER DIRADDO RECOMMENDED BY TAKE ACTION! Call on Russian authorities to protect journalists and other BOOK CLUB human rights defenders —See page 10 Elena Milashina, journalist Moscow-based newspaper Novaya Gazeta The Amnesty International Book Club is pleased to Thank you for being part of the Amnesty International announce our July/August title Funny Boy by Shyam Book Club. We appreciate your interest and would Selvadurai. This title has been recommended by guest love to hear from you with any questions, suggestions reader Christopher DiRaddo, with whom you will explore or comments you may have. Just send us an email at the novel and read beyond the book to learn more about [email protected]. LGBTI issues that Amnesty works hard to bring to light. We think you will really enjoy Funny Boy. Happy reading! In this guide, you will find DiRaddo’s reflection on the book, as well as discussion questions, an Amnesty Background section, and an action you can take to call on Chechnya to stop abducting, killing, and torturing About Amnesty International men believed to be gay. Set in the mannered, lush world of upper middle Amnesty International is a global movement of more than seven million supporters, members and activists in over 150 countries class Tamils in Sri Lanka, Funny Boy, though not and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. autobiographical, draws on Selvadurai’s experience of being gay in Sri Lanka and growing up during the Our vision is for all people to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the escalating violence between the Buddhist Sinhala Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international majority and Hindu Tamil minority in the 1970’s and early human rights standards.