The Uss Arizona Memorial and Visitor Center

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Native Hawaiian and Japanese American Discourse Over Hawaiian Statehood

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons Kevin and Tam Ross Undergraduate Research Prize Leatherby Libraries Spring 2021 3rd Place Contest Entry: Sovereignty, Statehood, and Subjugation: Native Hawaiian and Japanese American Discourse over Hawaiian Statehood Nicole Saito Chapman University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/undergraduateresearchprize Part of the American Politics Commons, American Studies Commons, Asian American Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, Ethnic Studies Commons, Hawaiian Studies Commons, History of the Pacific Islands Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, Other History Commons, Other Political Science Commons, Political History Commons, Public History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Saito, Nicole, "3rd Place Contest Entry: Sovereignty, Statehood, and Subjugation: Native Hawaiian and Japanese American Discourse over Hawaiian Statehood" (2021). Kevin and Tam Ross Undergraduate Research Prize. 30. https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/undergraduateresearchprize/30 This Contest Entry is brought to you for free and open access by the Leatherby Libraries at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kevin and Tam Ross Undergraduate Research Prize by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Research and Library Resources Essay My thesis was inspired by the article “Why Asian Settler Colonialism Matters” by sociologist Dean Saranillio, which chronicles Asian Americans’ marginalization of Native Hawaiians. As an Asian American from Hawaii, I was intrigued by this topic. My project thus investigates the consequences Japanese American advocacy for Hawaiian statehood had on Native Hawaiians. Based on the Leatherby Library databases that Rand Boyd recommended, I started my research by identifying key literature through Academic Search Premier and JSTOR. -

Douglas Close Call

AUGUST 2020 INSIDE: Arizona Memorial Boat Tours reopen Hurricane ADouglas Close Call Pearl Harbor and the End of World War II HAWAII PHOTO OF THE MONTH Your Navy Team in Hawaii CONTENTS Commander, Navy Region Hawaii oversees two installations: Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam on PREPAREDNESS Oahu and Pacific Missile Range Facility, Barking Sands, on Kauai. As Naval Surface Group Middle A Close Call Director of Public Aff airs, Navy Region Hawaii Pacific, we provide oversight for the ten surface Highlights of Hurricane Lydia Robertson ships homeported at JBPHH. Navy aircraft Douglas squadrons are also co-located at Marine Corps Deputy Director of Public Aff airs, Base Hawaii, Kaneohe, Oahu, and training is Navy Region Hawaii sometimes also conducted on other islands, but Mike Andrews most Navy assets are located at JBPHH and PMRF. These two installations serve fleet, fighter │4-5 Director of Public Aff airs, and family under the direction of Commander, Navy Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam Installations Command. ENVIRONMENTAL Chuck Anthony A guided-missile cruiser and destroyers of MDSU-1, NAVSEA Director of Public Aff airs, Commander, Naval Surface Force Pacific deploy remove FORACS Commander, Navy Region Pacifi c Missile Range Facility equipment off Nanakuli Tom Clements independently or as part of a group for Commander, Hawaii And Naval Surface Group U.S. Third Fleet and in the Seventh Fleet and Fifth Middle Pacifi c Managing Editor Fleet areas of responsibility. The Navy, including Anna Marie General your Navy team in Hawaii, builds partnerships and REAR ADM. ROBERT CHADWICK strengthens interoperability in the Pacific. Each │6-7 Military Editor year, Navy ships, submarines and aircraft from MC2 Charles Oki Hawaii participate in various training exercises with COVER STORY allies and friends in the Pacific and Indian Oceans to Contributing Staff strengthen interoperability. -

Welcome to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Asian Pacific Islander Desi American Community 2 0 Asiantation Table of Contents

2 0 Asiantation Welcome to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Asian Pacific Islander Desi American Community 2 0 Asiantation Table of Contents 1 "Asiantation Not Orientation" 2 Welcome to Asiantation 3 About Asiantation 4 AACC-Affiliated Registered Student Organizations 16 Other Registered Student Organizations AACC 17 17 | About the AACC 18 | Programs & Services 20 | International Education 21 | Facility 22 Asian American Studies 23 Academic Departments 24 Arts & Entertainment 25 Campus Resources 28 Student Publications 28 | "Unlearn" 29 | "Asian American Awareness" 30 | "Mental Health" 31 | "Date a Filipino" 32 | "Voting: Why?" "Asiantation Not Orientation" Why is it called Asiantation instead of Orientation? The title did not come out of nowhere - this poem describes it best. ASIAN ORIENTAL is not is a fad: yin-yang, kung fu Oriental. "say one of them funny words for me" Head bowed, submissive, industrious Oriental is downcast eyes, china doll hard working, studious "they all look alike" quiet Oriental is sneaky Oriental is a white man's word. ASIAN is not being Oriental, WE Lotus blossom, exotic passion flower are not Oriental. inscrutable we have heard the word all our lives we have learned to be Oriental ASIAN we have learned to live it, speak it, is not talking play the role, Oriental. and to survive in a white world ahh so, ching chong chinaman become the role. no tickee, no washee The time has come to look at who gave the name ORIENTAL is a white man's word. Anonymous Oriental is jap, flip, chink, gook it's "how 'bout a backrub mama-san" it's "you people could teach them niggers and mexicans a thing or two you're good people none of that hollerin' and protesting" This poem has appeared in every Asiantation Resource Booklet since its origination. -

The USS Arizona Memorial

National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places U.S. Department of the Interior Remembering Pearl Harbor: The USS Arizona Memorial Remembering Pearl Harbor: The USS Arizona Memorial (National Park Service Photo by Jayme Pastoric) Today the battle-scarred, submerged remains of the battleship USS Arizona rest on the silt of Pearl Harbor, just as they settled on December 7, 1941. The ship was one of many casualties from the deadly attack by the Japanese on a quiet Sunday that President Franklin Roosevelt called "a date which will live in infamy." The Arizona's burning bridge and listing mast and superstructure were photographed in the aftermath of the Japanese attack, and news of her sinking was emblazoned on the front page of newspapers across the land. The photograph symbolized the destruction of the United States Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor and the start of a war that was to take many thousands of American lives. Indelibly impressed into the national memory, the image could be recalled by most Americans when they heard the battle cry, "Remember Pearl Harbor." More than a million people visit the USS Arizona Memorial each year. They file quietly through the building and toss flower wreaths and leis into the water. They watch the iridescent slick of oil that still leaks, a drop at a time, from ruptured bunkers after more than 50 years at the bottom of the sea, and they read the names of the dead carved in marble on the Memorial's walls. National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places U.S. Department of the Interior Remembering Pearl Harbor: The USS Arizona Memorial Document Contents National Curriculum Standards About This Lesson Getting Started: Inquiry Question Setting the Stage: Historical Context Locating the Site: Map 1. -

Senator Spark M. Matsunaga Papers

Senator Spark M. Matsunaga Papers Finding Aid Hawaii Congressional Papers Collection Archives & Manuscripts Department University of Hawaii at Manoa Library January 2005 Table of Contents Introductory Information ……………………………………………………………….. 1 Administrative Information …………………..………………………………………… 2 Biographical Sketch …………………..………………………………………………….. 3 Biographical Chronology ………………………………………………………………... 4 Scope & Content Note …………..……………..………………………….……………… 8 Series Descriptions …….…………..………..…………………….……………………… 10 Series, Subseries & Sub-subseries Listing …………………………………………..… 14 Inventory …………………………..…………..……………………….……… Upon request Introductory Information Collection Name: Senator Spark M. Matsunaga Papers Accession Number: HCPC 1997.01 Inclusive Dates: 1916-1990 (bulk 1963-1990) Size of Collection: 908 linear feet Creator of Papers: Spark Masayuki Matsunaga Abstract: Spark Matsunaga (1916-1990) was a member of Congress from Hawaii, serving in the U.S. House of Representatives (1963-1976) and the U.S. Senate (1977-1990). He started his political career as an assistant public prosecutor in Honolulu (1952-1954), was a Representative in the Territory of Hawaii Legislature (1954-1959), worked tirelessly for Hawaii statehood, and was also a lawyer in private practice. He served in the U.S. Army, in the famed 100 th Infantry Battalion during WWII, receiving the Bronze Star and two Purple Hearts. He married Helene Hatsumi Tokunaga in 1948 and had five children. The bulk of the collection is from Matsunaga’s years in Congress and includes correspondence, photographs, audiovisual items, and memorabilia. The largest parts of this material concern Congressional activity supporting his strong interest in peace, space exploration, veterans, transportation, taxation, health, natural resources and civil rights, especially redress for Japanese Americans interned in WWII. His legendary hosting of constituents in Congressional dining rooms is shown in many invoices and guest lists. His staff kept detailed information on his schedules, appointments and travels. -

The Weeping Monument: a Pre and Post Depositional Site

THE WEEPING MONUMENT: A PRE AND POST DEPOSITIONAL SITE FORMATION STUDY OF THE USS ARIZONA by Valerie Rissel April, 2012 Director of Thesis: Dr. Brad Rodgers Major Department: Program in Maritime History and Archaeology Since its loss on December 7, 1941, the USS Arizona has been slowly leaking over 9 liters of oil per day. This issue has brought about conversations regarding the stability of the wreck, and the possibility of defueling the 500,000 to 600,000 gallons that are likely residing within the wreck. Because of the importance of the wreck site, a decision either way is one which should be carefully researched before any significant changes occur. This research would have to include not only the ship and its deterioration, but also the oil’s effects on the environment. This thesis combines the historical and current data regarding the USS Arizona with case studies of similar situations so a clearer picture of the future of the ship can be obtained. THE WEEPING MONUMENT: A PRE AND POST DEPOSITIONAL SITE FORMATION STUDY OF THE USS ARIZONA Photo courtesy of Battleship Arizona by Paul Stillwell A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Program in Maritime Studies Department of History East Carolina University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Masters in Maritime History and Archaeology by Valerie Rissel April, 2012 © Valerie Rissel, 2012 THE WEEPING MONUMENT: A PRE AND POST DEPOSITIONAL SITE FORMATION STUDY OF THE USS ARIZONA by Valerie Rissel APPROVED BY: DIRECTOR OF THESIS______________________________________________________________________ Bradley Rodgers, Ph.D. COMMITTEE MEMBER________________________________________________________ Michael Palmer, Ph.D. -

Pearl Harbor

INSIDE Hawaii Military Week Events A-2 Word on the Street A-3 Radio Recon Screening A-4 SACO of the Quarter A-6 Every Clime and Place A-8 Asian/Pacific Heritage B-1 MCCS B-2 Sports B-3 Windward Half Marathon B-4 M ARINEARINEMarine Makeponos B-5 VolumeM 30, Number 19 www.mcbh.usmc.mil May 24, 2001 Epic premiers on Oahu Camp Smith Marine honored Cpl. Jacques-René Hébert MarForPac Public Affairs CAMP H.M. SMITH – A product from a diverse past, his parents had crossed archaic and outdated social and cultural lines to make a life together. His father was full-blooded Jewish, while his mother was half Spanish and half Puerto Rican. The two met in his father’s native Brooklyn, N.Y and eventually settled there. A city of asphalt and anger, poetry and police, Brooklyn boasts a patchwork of neighborhoods that vary drastically in nationality and cultural identities. But for 1st Sgt. Harry Rivera of Headquarters and Service Co., Camp H.M. Smith, his upbringing was filled with love and discipline, which shel- tered him from the hard New York streets. “New York’s diversity gave me an op- portunity to see from many different perspectives,” Rivera reflected. “My father was firm,” he remem- bered. “Whatever I did, he stressed that I do it to the best of my ability.” Image by Andrew Cooper for Touchstone Pictures And this he did. Rivera was recog- A stupendous air attack upon Pearl Harbor by bombers from the Imperial Empire of Japan shatters the world and changes the nized as Marine Corps Times “Marine course of history, in Touchstone Pictures’ epic drama, “Pearl Harbor,” which opens in theaters Friday. -

DI CP19 F1 Ocrcombined.Pdf

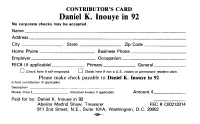

CONTRIBUTOR’S CARD Daniel K. Inouye in 92 No corporate checks may be accepted. Name ______________________________________________________________________ Address ____________________________________________________________________ C ity _________________ S ta te ___________________ Zip C ode __________________ Home Phone ________________________ Business Phone ________________________ Employer ____________________________ Occupation ___________________________ FEC# (if applicable) _____________ Primary ______________ General ______________ d l Check here if self-employed. CH Check here if not a U.S. citizen or permanent resident alien. Please make check payable to Daniel K. Inouye in 92 In-kind contribution (if applicable) Description ___________________________________________________ Market Price $ _____________________ (Attached invoice if applicable) Amount _$ ___________________ Paid for by: Daniel K. Inouye in 92 ______________ Abelina Madrid Shaw, Treasurer FEC # C00213314 911 2nd Street, N.E., Suite 101 A, Washington, D.C. 20002 This information is required of all contributions by the Federal Election Campaign Act. Corporation checks or funds, funds from government contractors and foreign nationals, and contributions made in the name of another cannot be accepted. Contributions or gifts to Daniel K. Inouye in 92 are not tax deductible. A copy of our report is on file with the Federal Election Commission and is available for purchase from the Federal Election Commission, Washington, D.C. 20463. JUN 18 '92 12=26 SEN. INOUYE CAMPAIGN 808 5911005 P.l 909 KAPIOLANI BOULEVARD HONOLULU, HAWAII 96814 (808) 591-VOTE (8683) 591-1005 (Fax) FACSIMILE TRANSMISSION TO; JENNIFER GOTO FAX#: NESTOR GARCIA FROM: KIMI UTO DATE; JUNE 1 8 , 1992 SUBJECT: CAMPAIGN WORKSHOP Number of pages Including this cover sheet: s Please contact K im i . at (808) 591-8683 if you have any problems with this transmission. -

F—18 Navy Air Combat Fighter

74 /2 >Af ^y - Senate H e a r tn ^ f^ n 12]$ Before the Committee on Appro priations (,() \ ER WIIA Storage ime nts F EB 1 2 « T H e -,M<rUN‘U«sni KAN S A S S F—18 Na vy Air Com bat Fighter Fiscal Year 1976 th CONGRESS, FIRS T SES SION H .R . 986 1 SPECIAL HEARING F - 1 8 NA VY AIR CO MBA T FIG H TER HEARING BEFORE A SUBC OMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE NIN ETY-FOURTH CONGRESS FIR ST SE SS IO N ON H .R . 9 8 6 1 AN ACT MAKIN G APP ROPR IA TIO NS FO R THE DEP ARTM EN T OF D EFEN SE FO R T H E FI SC AL YEA R EN DI NG JU N E 30, 1976, AND TH E PE RIO D BE GIN NIN G JU LY 1, 1976, AN D EN DI NG SEPT EM BER 30, 1976, AND FO R OTH ER PU RP OSE S P ri nte d fo r th e use of th e Com mittee on App ro pr ia tio ns SPECIAL HEARING U.S. GOVERNM ENT PRINT ING OFF ICE 60-913 O WASHINGTON : 1976 SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS JOHN L. MCCLELLAN, Ark ans as, Chairman JOH N C. ST ENN IS, Mississippi MILTON R. YOUNG, No rth D ako ta JOH N O. P ASTORE, Rhode Island ROMAN L. HRUSKA, N ebraska WARREN G. MAGNUSON, Washin gton CLIFFORD I’. CASE, New Je rse y MIK E MANSFIEL D, Montana HIRAM L. -

House Stalls Emergency Appropriation Bill with $250 Million

News land: 25¢ (SOC Postpaid) "2.528 Vol. 108. No. 17 ISSN: 0030-8579 941 East 3rd St . Suite 200. Los Angeles, CA 90013 (213) 626-6936 Friday, May 5,1989 House Stalls Emergency Appropriation Bill With $250 Million Redress Payment WASHINGTON-Momentum for an The Foley amendment wa defeated emergency spending bill containing priation Committee Chaimlan Jamie 172 to 252. Whitten (D-Mi . ) $250 million for redress payments wa A ub titute amendment by Rep. temporarily stalled on the House floor Matsui al 0 aid another important Silvio O. Conte (R-Ma .), which debate i curr ntly going on in the lhi past week (April 26) a the meas would have cut $1.8 billion from ure was ent back to committee for Hou e Budget Committee where law the $4.7 billion mea ure including makers will oon detemline how much "corrective surgery," according to $250 million for redre ,wa not Rep. Robert T. Matsui (D.-Calif.). money redre will receive in the 1990 introduced. budget. The $4.7 billion measure, H.R. Many who voted "nay" to Foley's 2027, was termed the "dire emergency Rep . Don Edward (D-Calif.). amendment did 0 becau e of their chairman of the Hou e Judiciary ub supplemental appropriation act." It opposition to cuts in defense and contain $250 million for redre s pay committee on civil and con titutional dome tic program . While redres right , declared: ments in 1989 plus $6.4 million for was not a central point of the floor administrative cost . debate, ome made comments. uch "It wa the considered judgment of eal Members had debated for 5 \12 hours Smith, chainnan of the Appropriations as: subcommittee on commerce , justice, state in a lively and emotional manner. -

![CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8733/chairmen-of-senate-standing-committees-table-5-3-1789-present-978733.webp)

CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present

CHAIRMEN OF SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–present INTRODUCTION The following is a list of chairmen of all standing Senate committees, as well as the chairmen of select and joint committees that were precursors to Senate committees. (Other special and select committees of the twentieth century appear in Table 5-4.) Current standing committees are highlighted in yellow. The names of chairmen were taken from the Congressional Directory from 1816–1991. Four standing committees were founded before 1816. They were the Joint Committee on ENROLLED BILLS (established 1789), the joint Committee on the LIBRARY (established 1806), the Committee to AUDIT AND CONTROL THE CONTINGENT EXPENSES OF THE SENATE (established 1807), and the Committee on ENGROSSED BILLS (established 1810). The names of the chairmen of these committees for the years before 1816 were taken from the Annals of Congress. This list also enumerates the dates of establishment and termination of each committee. These dates were taken from Walter Stubbs, Congressional Committees, 1789–1982: A Checklist (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985). There were eleven committees for which the dates of existence listed in Congressional Committees, 1789–1982 did not match the dates the committees were listed in the Congressional Directory. The committees are: ENGROSSED BILLS, ENROLLED BILLS, EXAMINE THE SEVERAL BRANCHES OF THE CIVIL SERVICE, Joint Committee on the LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LIBRARY, PENSIONS, PUBLIC BUILDINGS AND GROUNDS, RETRENCHMENT, REVOLUTIONARY CLAIMS, ROADS AND CANALS, and the Select Committee to Revise the RULES of the Senate. For these committees, the dates are listed according to Congressional Committees, 1789– 1982, with a note next to the dates detailing the discrepancy. -

The Daniel K Inouye Institute Has Been Working Hard to Share the Senator's Legacy Across the Country from Maine, to Washington DC, and of Course, Right Here in Hawaii

September 23, 2019 Dear Friends: It's been a busy summer! The Daniel K Inouye Institute has been working hard to share the Senator's legacy across the country from Maine, to Washington DC, and of course, right here in Hawaii. So much so that we are breaking our updates into 2 newsletters! Christening of the Daniel Inouye (DDG 118) On June 21-22, 2019 the DKI ohana gathered in Bath, Maine for the christening of the Navy Destroyer Daniel Inouye (DDG 118), which will arrive in its homeport of Pearl Harbor in early 2021 under the leadership of Commanding Officer CDR DonAnn Gilmore, Master Chief Thomas Mace, and more than 300 sailors. We are honored that the USS Daniel Inouye’s first commander will be a woman. Hawai‘i Community Foundation • 827 Fort Street Mall • Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96813 • 808.537.6333 www.danielkinouyeinstitute.org Just getting to Maine was a monumental task! We deiced that a plastic lei on the DANIEL INOUYE just would not do, so we went to work. Thanks to support from Brion Chang and his team, 8 segments -- feet each, a massive ti-leaf lei (tied to a 1-inch diameter rope), which when assembled stretched 75 feet - a double strand lei. Watch this video to see the lei being assembled at the shipyard upon our arrival. https://youtu.be/XTi5d9OV0PU. The shipyard staff was eager to learn how to build the lei, and really enjoyed seeing the beautiful flowers. In addition, we brought 4 dozen lei for dignitaries, together with Big Island Candies, Kauai's special salt and a host of omiyage for special guests.