Final Thesis Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City of Johannesburg Ward Councillors: Region F

CITY OF JOHANNESBURG WARD COUNCILLORS: REGION F No. Councillors Party Region Ward Ward Suburbs: Ward Administrator: Name/Surname & Contact : : No: Details: 1. Cllr. Sarah Wissler DA F 23 Glenvista, Glenanda, Nombongo Sitela 011 681- [email protected] Mulbarton, Bassonia, Kibler 8094 011 682 2184 Park, Eikenhof, Rispark, [email protected] 083 256 3453 Mayfield Park, Aspen Hills, Patlyn, Rietvlei 2. VACANT DA F 54 Mondeor, Suideroord, Alan Lijeng Mbuli Manor, Meredale, Winchester 011 681-8092 Hills, Crown Gardens, [email protected] Ridgeway, Ormonde, Evans Park, Booysens Reserve, Winchester Hills Ext 1 3. Cllr Rashieda Landis DA F 55 Turffontein, Bellavista, Lijeng Mbuli [email protected] Haddon, Lindberg Park, 011 681-8092 083 752 6468 Kenilworth, Towerby, Gillview, [email protected] Forest Hill, Chrisville, Robertsham, Xavier and Golf 4. Cllr. Michael Crichton DA F 56 Rosettenville, Townsview, The Lijeng Mbuli [email protected] Hill, The Hill Extension, 011 681-8092 083 383 6366 Oakdene, Eastcliffe, [email protected] Linmeyer, La Rochelle (from 6th Street South) 5. Cllr. Faeeza Chame DA F 57 Moffat View, South Hills, La Nombongo Sitela [email protected] Rochelle, Regents Park& Ext 011 681-8094 081 329 7424 13, Roseacre1,2,3,4, Unigray, [email protected] Elladoon, Elandspark, Elansrol, Tulisa Park, Linmeyer, Risana, City Deep, Prolecon, Heriotdale, Rosherville 6. Cllr. A Christians DA F 58 Vredepark, Fordsburg, Sharon Louw [email protected] Laanglagte, Amalgam, 011 376-8618 011 407 7253 Mayfair, Paginer [email protected] 081 402 5977 7. Cllr. Francinah Mashao ANC F 59 Joubert Park Diane Geluk [email protected] 011 376-8615 011 376-8611 [email protected] 082 308 5830 8. -

BUILDING from SCRATCH: New Cities, Privatized Urbanism and the Spatial Restructuring of Johannesburg After Apartheid

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF URBAN AND REGIONAL RESEARCH 471 DOI:10.1111/1468-2427.12180 — BUILDING FROM SCRATCH: New Cities, Privatized Urbanism and the Spatial Restructuring of Johannesburg after Apartheid claire w. herbert and martin j. murray Abstract By the start of the twenty-first century, the once dominant historical downtown core of Johannesburg had lost its privileged status as the center of business and commercial activities, the metropolitan landscape having been restructured into an assemblage of sprawling, rival edge cities. Real estate developers have recently unveiled ambitious plans to build two completely new cities from scratch: Waterfall City and Lanseria Airport City ( formerly called Cradle City) are master-planned, holistically designed ‘satellite cities’ built on vacant land. While incorporating features found in earlier city-building efforts, these two new self-contained, privately-managed cities operate outside the administrative reach of public authority and thus exemplify the global trend toward privatized urbanism. Waterfall City, located on land that has been owned by the same extended family for nearly 100 years, is spearheaded by a single corporate entity. Lanseria Airport City/Cradle City is a planned ‘aerotropolis’ surrounding the existing Lanseria airport at the northwest corner of the Johannesburg metropole. These two new private cities differ from earlier large-scale urban projects because everything from basic infrastructure (including utilities, sewerage, and the installation and maintenance of roadways), -

Company Profile 2019/20

Company Profile 2019/20 Fourways Airconditioning: a story of continuous growth and expansion From selling home airconditioning units from a small outlet in 1999, Fourways Airconditioning has grown to become a national – and international – operation, offering a wide range of aircons as well as Domestic and Commercial Heat Pumps plus home appliances. Fourways Airconditioning began as a small company in Kya-Sands selling Samsung airconditioners to COD customers in 1999. Since those early days, Fourways Johannesburg has expanded twice to new premises, while our Pretoria branch, established in 2009 to serve local customers, has also moved premises to accommodate ever-increasing volumes. Appointed as authorised importers and distributors of Samsung airconditioners in South Africa in 2004, Fourways supplies everything from small domestic split units to large Samsung DVM units. In 2006, Fourways also launched its own range of Alliance airconditioners and Heat Pumps. OUR VISION OUR MISSION To become the No. 1 Supplier of To provide our dealers – and customers – with Airconditioning and Heat Pumps units, the best-quality units, backed up by the best spares and service in South Africa. service and marketed by top-class people in a responsible and strategic manner. Our Samsung range of products Fourways Airconditioning stocks and sells a wide range of Samsung airconditioners from small midwall splits up to large DVM S units and Chillers offering world-class energy efficiency. Our Samsung product range includes split airconditioners, cassette units, ducted units, Free Joint Multis, underceilings and floor standing airconditioners (all available in inverter and non-inverter form). Samsung’s large DVM S is an innovative system utilizing new 3rd generation Samsung Scroll Compressor technology. -

Middle Classing in Roodepoort Capitalism and Social Change in South Africa

Middle Classing in Roodepoort Capitalism and Social Change in South Africa Ivor Chipkin June 2012 / PARI Long Essays / Number 2 Contents Acknowledgements ..................................................................................... 3 Preface ........................................................................................................ 5 Introduction: A Common World ................................................................. 7 1. Communal Capitalism ....................................................................... 13 2. Roodepoort City ................................................................................ 28 3.1. The Apartheid City ......................................................................... 33 3.2. Townhouse Complexes ............................................................... 35 3. Middle Class Settlements ................................................................... 41 3.1. A Black Middle Class ..................................................................... 46 3.2. Class, Race, Family ........................................................................ 48 4. Behind the Walls ............................................................................... 52 4.1. Townhouse and Suburb .................................................................. 52 4.2. Milky Way.................................................................................. 55 5. Middle-Classing................................................................................. 63 5.1. Blackness -

Alexandra Urban Renewal:- the All-Embracing Township Rejuvenation Programme

ALEXANDRA URBAN RENEWAL:- THE ALL-EMBRACING TOWNSHIP REJUVENATION PROGRAMME 1. Introduction and Background About the Alexandra Township The township of Alexandra is one of the densely populated black communities of South Africa reach in township culture embracing cultural diversity. This township is located about 12km (about 7.5 miles) north-east of the Johannesburg city centre and 3km (less than 2 miles) from up market suburbs of Kelvin, Wendywood and Sandton, the financial heart of Johannesburg. It borders the industrial areas of Wynberg, and is very close to the Limbro Business Park, where large parts of the city’s high-tech and service sector are based. It is also very near to Bruma Commercial Park and one of the hype shopping centres of Eastgate Shopping Centre. This township amongst the others has been the first stops for rural blacks entering the city in search for jobs, and being neighbours with the semi-industrial suburbs of Kew and Wynberg. Some 170 000 (2001 Census: 166 968) people live in this community, in an area of approximately two square kilometres. Alexandra extends over an area of 800 hectares (or 7.6 square kilometres) and it is divided by the Jukskei River. Two of the main feeder roads into Johannesburg, N3 and M1 pass through Alexandra. However, the opportunity to link Alexandra with commercial and industrial areas for some time has been low. Socially, Alexandra can be subdivided into three parts, with striking differences; Old Alexandra (west of the Jukskei River) being the poorest and most densely populated area, where housing is mainly in informal dwellings and hostels. -

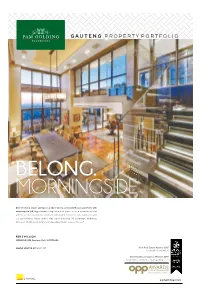

Gauteng Property Portfolio

GAUTENG PROPERTY PORTFOLIO BELONG. MORNINGSIDE One-of-a-kind, secure and spacious triple-storey, corner penthouse apartment, with uninterrupted 270-degree views. Refrigerated walk-in wine room, 4 palatial bedrooms with the wooden floor theme continued, with marble covered en suite bathrooms and a state-of-the-art home cinema with top-of-the-range AV equipment. Numerous balconies, all with views, with a heated pool and steam-room on the roof. R39.5 MILLION MORNINGSIDE, Gauteng Ref# HP1139604 WAYNE VENTER 073 254 1453 Best Real Estate Agency 2015 South Africa and Africa Best Real Estate Agency Website 2015 South Africa and Africa / pamgolding.co.za pamgolding.co.za EXERCISE YOUR FREEDOM 40KM HORSE RIDING TRAILS Our ultra-progressive Equestrian Centre, together with over 40 kilometres of bridle paths, is a dream world. Whether mastering an intricate dressage movement, fine-tuning your jump approach, or enjoying an exhilarating outride canter, it is all about moments in the saddle. The accomplished South African show jumper, Johan Lotter, will be heading up this specialised unit. A standout health feature of our Equestrian Centre is an automated horse exerciser. Other premium facilities include a lunging ring, jumping shed, warm-up arena and a main arena for show jumping and dressage events. The total infrastructure includes 36 stables, feed and wash areas, tack- rooms, office, medical rooms and groom accommodation. Kids & Teens Wonderland · Sport & Recreation · Legendary Golf · Equestrian · Restaurants & Retail · Leisure · Innovative Infrastructure -

Metropolis in Sophiatown Today, the Executive Mayor of the City Of

19 July 2013: Metropolis in Sophiatown Today, the Executive Mayor of the City of Johannesburg, Cllr Mpho Parks Tau, launched an Xtreme Park in Sophiatown while closing the annual Metropolis 2013 meeting held in Sandton, Joburg from Tuesday. At the launch, the Executive Mayor paid tribute to the vibrancy, multi-cultural and multi-racial buoyancy of Sophiatown, a place that became the lightning rod of both the anti-apartheid movement as well as the apartheid government's racially segregated and institutionalised policy of separate development. In February 1955 over 65 000 residents from across the racial divide were forcibly removed from Sophiatown and placed in separate development areas as they were considered to be too close to white suburbia. Sophiatown received a 48 hour Xtreme Park makeover courtesy of the City as part of its urban revitalisation and spatial planning programme. Said Mayor Tau: "The Xtreme Park concept was directed at an unused piece of land and turning it into a luscious green park. The park now consists of water features, play equipment for children, garden furniture and recreational facilities. Since 2007 the city has completed a number of Xtreme Parks in various suburbs including Wilgeheuwel, Diepkloof, Protea Glen, Claremont, Pimville and Ivory Park. As a result, Joburg's City Parks was awarded a gold medal by the United Nations International Liveable Communities award in 2008. "Today we are taking the Xtreme Parks concept into Sophiatown as part of our urban revitalisation efforts in this part of the city. Our objective is to take an under- utilised space, that is characterized by illegal dumping, graffiti, and often the venue for petty crime and alcohol and drug abuse; and transform it into a fully-fledged, multi-functional park," the Mayor said. -

Memories of Johannesburg, City of Gold © Anne Lapedus

NB This is a WORD document, you are more than Welcome to forward it to anyone you wish, but please could you forward it by merely “attaching” it as a WORD document. Contact details For Anne Lapedus Brest [email protected] [email protected]. 011 783.2237 082 452 7166 cell DISCLAIMER. This article has been written from my memories of S.Africa from 48 years ago, and if A Shul, or Hotel, or a Club is not mentioned, it doesn’t mean that they didn’t exist, it means, simply, that I don’t remember them. I can’t add them in, either, because then the article would not be “My Memories” any more. MEMORIES OF JOHANNESBURG, CITY OF GOLD Written and Compiled By © ANNE LAPEDUS BREST 4th February 2009, Morningside, Sandton, S.Africa On the 4th February 1961, when I was 14 years old, and my brother Robert was 11, our family came to live in Jhb. We had left Ireland, land of our birth, leaving behind our beloved Grandparents, family, friends, and a very special and never-to-be-forgotten little furry friend, to start a new life in South Africa, land of Sunshine and Golden opportunity…………… The Goldeneh Medina…... We came out on the “Edinburgh Castle”, arriving Cape Town 2nd Feb 1961. We did a day tour of Chapmans Peak Drive, Muizenberg, went to somewhere called the “Red Sails” and visited our Sakinofsky/Yodaiken family in Tamboerskloof. We arrived at Park Station (4th Feb 1961), Jhb, hot and dishevelled after a nightmarish train ride, breaking down in De Aar and dying of heat. -

![Our Hillbrow, Not Only to Move in and out of the “Physical and the Metaphysical Sphere[S]” Effectively but Also to Employ a Communal Mode of Narrative Continuity](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3689/our-hillbrow-not-only-to-move-in-and-out-of-the-physical-and-the-metaphysical-sphere-s-effectively-but-also-to-employ-a-communal-mode-of-narrative-continuity-733689.webp)

Our Hillbrow, Not Only to Move in and out of the “Physical and the Metaphysical Sphere[S]” Effectively but Also to Employ a Communal Mode of Narrative Continuity

Introduction ghirmai negash haswane Mpe (1970–2004) was one of the major literary talents to emerge in South PAfrica after the fall of apartheid. A graduate in African literature and English from the Univer- sity of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, he was a nov- elist, poet, scholar, and cultural activist who wrote with extraordinary commitment and originality, both in substance and in form. His intellectual honesty in exploring thematic concerns germane to postapartheid South African society continues to inspire readers who seek to reflect on old and new sets of problems facing the new South Africa. And his style continues to set the bar for many aspiring black South African writers. Mpe’s writing is informed by an oral tradition par- ticular to the communal life of the South African xii Introduction pastoral area of Limpopo. This, in addition to his modern university liberal arts education; his experi- ence of urban life in Johannesburg; and, ultimately, his artistic sensibility and ability to synthesize dis- parate elements, has marked him as a truly “home- grown” South African literary phenomenon. It is no wonder that the South African literary commu- nity was struck by utter shock and loss in 2004 when the author died prematurely at the age of thirty- four. In literary historical terms, Mpe’s early death was indeed a defining moment.I n an immediate way, his South African compatriots—writers, critics, and cultural activists—were jolted into awareness of what the loss of Mpe as a unique literary fig- ure meant for South African literary tradition. In terms of his legacy, it was also a moment of acute revelation that the force and form of his work was a motivating influence for, just as it was inspired by, the emergence of many more writers of consider- able talent. -

Directory of Organisations and Resources for People with Disabilities in South Africa

DISABILITY ALL SORTS A DIRECTORY OF ORGANISATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA University of South Africa CONTENTS FOREWORD ADVOCACY — ALL DISABILITIES ADVOCACY — DISABILITY-SPECIFIC ACCOMMODATION (SUGGESTIONS FOR WORK AND EDUCATION) AIRLINES THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS ARTS ASSISTANCE AND THERAPY DOGS ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR HIRE ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR PURCHASE ASSISTIVE DEVICES — MAIL ORDER ASSISTIVE DEVICES — REPAIRS ASSISTIVE DEVICES — RESOURCE AND INFORMATION CENTRE BACK SUPPORT BOOKS, DISABILITY GUIDES AND INFORMATION RESOURCES BRAILLE AND AUDIO PRODUCTION BREATHING SUPPORT BUILDING OF RAMPS BURSARIES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — EASTERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — FREE STATE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — GAUTENG CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — KWAZULU-NATAL CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — LIMPOPO CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — MPUMALANGA CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTHERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTH WEST CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — WESTERN CAPE CHARITY/GIFT SHOPS COMMUNITY SERVICE ORGANISATIONS COMPENSATION FOR WORKPLACE INJURIES COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES CONVERSION OF VEHICLES COUNSELLING CRÈCHES DAY CARE CENTRES — EASTERN CAPE DAY CARE CENTRES — FREE STATE 1 DAY CARE CENTRES — GAUTENG DAY CARE CENTRES — KWAZULU-NATAL DAY CARE CENTRES — LIMPOPO DAY CARE CENTRES — MPUMALANGA DAY CARE CENTRES — WESTERN CAPE DISABILITY EQUITY CONSULTANTS DISABILITY MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS DISABILITY MANAGEMENT DISABILITY SENSITISATION PROJECTS DISABILITY STUDIES DRIVING SCHOOLS E-LEARNING END-OF-LIFE DETERMINATION ENTREPRENEURIAL -

A Case Study on South Africa's First Shipping Container Shopping

Local Public Space, Global Spectacle: A Case Study on South Africa’s First Shipping Container Shopping Center by Tiffany Ferguson BA in Dance BA Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Urban America Hunter College of the City University of New York (2010) Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in City Planning at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2018 © 2018 Tiffany Ferguson. All Rights Reserved The author hereby grants to MIT the permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of the thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Author____________________________________________________________________ Department of Urban Studies and Planning May 24, 2018 Certified by_________________________________________________________________ Assistant Professor of Political Economy and Urban Planning, Jason Jackson Department of Urban Studies and Planning Thesis Supervisor Accepted by________________________________________________________________ Professor of the Practice, Ceasar McDowell Department of Urban Studies and Planning Chair, MCP Committee 2 Local Public Space, Global Spectacle: A Case Study on South Africa’s First Shipping Container Shopping Center by Tiffany Ferguson Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on May 24, 2018 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in City Planning Abstract This thesis is the explication of a journey to reconcile Johannesburg’s aspiration to become a ‘spatially just world class African city’ through the lens of the underperforming 27 Boxes, a globally inspired yet locally contested retail center in the popular Johannesburg suburb of Melville. By examining the project’s public space, market, retail, and design features – features that play a critical role in its imagined local economic development promise – I argue that the project’s ‘failure’ can be seen through a prism of factors that are simultaneously local and global. -

Apartheid & the New South Africa

Apartheid & the New South Africa HIST 4424 MW 9:30 – 10:50 Pafford 206 Instructor: Dr. Molly McCullers TLC 3225 [email protected] Office Hours: MW 1-4 or by appointment Course Objectives: Explore South African history from the beginning of apartheid in 1948, to Democracy in 1994, through the present Examine the factors that caused and sustained a repressive government regime and African experiences of and responses to apartheid Develop an understanding of contemporary South Africa’s challenges such as historical memory, wealth inequalities, HIV/AIDS, and government corruption Required Texts: Books for this class should be available at the bookstore. They are all available online at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and Half.com. Many are available as ebooks. You can also obtain copies through GIL Express or Interlibrary Loan Nancy Clark & William Worger, South Africa: The Rise and Fall of Apartheid. (New York: Routledge) o Make sure to get the 2011 or 2013 edition. The 2004 edition is too old. o $35.00 new/ $22.00 ebook Clifton Crais & Thomas McLendon: The South Africa Reader: History, Culture, Politics (Duke: 2012) o $22.47 new/ $16.00 ebook Mark Mathabane, Kaffir Boy: An Autobiography – The True Story of a Black Youth’s Coming of Age in Apartheid South Africa (Free Press, 1998) o Any edition is fine o $12.88 new/ $8.99 ebook o On reserve at library & additional copies available Andre Brink, Rumors of Rain: A Novel of Corruption and Redemption (2008) o $16.73 new/ $10.99 ebook Rian Malan, My Traitor’s Heart: A South African Exile Returns to Face his Country, his Tribe, and his Conscience (2000) o $10.32 new/ $9.80 ebook o On reserve at Library Zakes Mda, The Heart of Redness: A Novel (2003) o $13.17 new / $8.99 ebook Jonny Steinberg, Sizwe’s Test: A Young Man’s Journey through Africa’s AIDS Epidemic (2010) o $20.54 new/ $14.24 ebook All additional readings will be available on Course Den Assignments: Reaction Papers – There will be 5 reaction papers to each of the books due over the course of the semester.