Gilcraft's Rover Scouts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Simplified BSA Volunteer Position Descriptions Wood Badge Project by Kent Nuttall Version August 27, 2018

Simplified BSA Volunteer Position Descriptions Wood Badge Project by Kent Nuttall Version August 27, 2018 Several Units and Districts struggle getting adults to volunteer especially for leadership positions. There are a variety of reasons for this struggle, including: • Parents today feel they are too busy to take on volunteer assignments • Parents asked perceive any Scout volunteer assignment will be too time consuming or is well above their ability • The current position descriptions spend undue focus on responsibilities, and look complex. This project focuses on simplifying position descriptions and changing their focus to highlight the few outputs expected along with resources that will help them succeed. Further support includes guidance for using the new position descriptions. FEEDBACK IS REQUESTED These are still in development. Please feel free to send feedback to [email protected]. Before using or sending feedback, read more about the position descriptions to understand the format and content provided. Using the Position Descriptions The position descriptions have the following design characteristics: • These are simple one-page descriptions that provide the essentials of the position. It is most helpful for asking volunteers to accept a position and in providing them their orientation. Over time, the leader will receive training and grow their skills beyond this simple description. • Instead of focusing on RESPONSIBILITIES, we’re focusing on the OUTPUTS we want to see. These are described in the table below. • Training, meetings, and resources are presented as those things that will help the leader succeed, not as a list of requirements. • They have been left as a Word file so you can modify them for your District or Unit. -

BAE Systems Normal.Dot

Waterlooville Scout District: Catherington: Clanfield: Cowplain: Denmead: Hambeldon: Hart Plain: Horndean: Purbrook: Waterlooville Issue 19 Waterlooville Scout District News and Views June 2013 WELCOME TO SCOUTING ! So far we have held two ‘Welcome to Scouting Sessions’. The first one had an amazing turnout of 12 newish people attend FIRST RESPONSE ADMINISTRATOR. as well as our District chairman Sue and Paul our Assistant County Commissioner Role – to do all the paperwork and make any for District Support. arrangements to see that Leaders are able to renew or obtain their certificates before they The recent recruits ranged from people who expire. had had an involvement with Scouting in an Hours of work – less than an hour a week unofficial capacity for many years to a (better than being a Leader who does 2 hours couple who were so new they hadn’t even a week) attended a Section meeting. The aim was to give them a brief outline of Scouting, the Rate of Pay – same as for a Leader. Group structure and training and they went away with a copy of the module 1 DVD to get their training underway. There was also Training will be provided. a chance to ask questions and have a chat Applications to the DC. with the people there to help support them Helen from Hambledon Village Group covered the structures sessions and Chris, RECENT AWARDS our Local training Manager, the training Service awards aspects. Ian Stott ADC Scouts 30 years service The sessions have been well received and Ross Sherrington ASL 2nd W’ville 30 years service can be attended by anyone not just Section Neil Storey ASL 1st Horndean 25 years service Leaders but also new members of Group Helene Moutray BSL 2nd W’ville 25 years service Executives who want to understand a bit Suzanne Stephens ASL 1st Hart Plain 10 years service more about what they have let themselves in for! Wood Badges The next Session will be on Saturday 22nd Jennifer Weller ABSL 1st Clanfield June at 1st Hart Plain HQ from 10.30 until about midday. -

BPSA and Rover Award Scheme

THE NEW BADEN-POWELL SCOUT AWARD AND ROVER SCOUT AWARD SCHEME Published by the Victorian Branch Rover Council Febrauary 2014 The New Baden-Powell Scout Award and Rover Scout Award Scheme Table of Contents Why$a$New$Award$Scheme?$...................................................................................................................$3! The$New$Award$Scheme$..........................................................................................................................$4! World$Membership$Badge$&$Rover$Scout$Link$Badge$..................................................................$6! Squire$Training$..........................................................................................................................................$7! Rover$Skills$..................................................................................................................................................$8! Service$...........................................................................................................................................................$9! Physical$.......................................................................................................................................................$10! St$George$Award$......................................................................................................................................$11! Community$Development$&$Personal$Growth$..............................................................................$12! Self$Reflection$Interview$......................................................................................................................$13! -

Scouting Around the World

Scouting around the World Hallvard Slettebö FRPSL The Royal Philatelic Society London 27 October 2016 Plan of the Display Frames Subject 1 – 12 World Scouting – its Path to Success The FIP large gold thematic exhibit “World Scouting – its Path to Success” has the accolade of achieving the highest award ever given to a philatelic Scouting exhibit. The exhibit demonstrates the significance of Baden-Powellʼs original conception and the development of Scouting to todayʼs world wide movement. 13 – 17 Scout Mail in Displaced Persons Camps A traditional exhibit, documenting local postage stamps, postmarks and mail delivery services related to Scouting, issued for and used by inhabitants in Displaced Persons camps in Europe after World War II. 18 – 22 Scouting in the United Kingdom Postal history related to the Scout and Guide movements in the UK up to 1957. This section of the display focuses on the postal history of the 1957 Jubilee Jamboree. 23 – 28 Scouting in Norway A postal history class 2C exhibit (Historical, Social and Special Studies), documenting postal history related to the Scout and Guide movements in Norway up to 1957. Postal usage of all thirty of the earliest Norwegian Scout postmarks is shown for the first time. 29 – 44 Scouting in Europe A potpourri of the postal history of Scouting in Europe up to 1957, presented by country and year. 45 – 52 Scouting Overseas A potpourri of the postal history of Scouting outside Europe up to 1957, presented by country and year. The significance of 1957 in Scouting history and in Scouting philately: 1957 marks the Golden Jubilee of Scouting and the centenary of the birth of Lord Baden-Powell. -

Commissioner Service, Our First Hundred Years

COMMISSIONER SERVICE, OUR FIRST HUNDRED YEARS A research thesis submitted to the College College of Commissioner Science Longhorn Council In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Commissioner Science Degree By Paul N Dreiseszun 2010 INTRODUCTION As we approach the 100th anniversary of Scouting and the Commissioner Service, we need to look back and salute those Scouters that have worn the insignia of the Commissioner. Scouting has changed in those many years. Requirements and uniforms have changed. Council structures and boundaries have been altered. But the role of the Commissioner as Scouting's conduit for unit service remains unchanged. I have been honored to serve as a Unit Commissioner, Assistant District Commissioner, and District Commissioner. My experience is that it can be the most difficult position in Scouting. But it can also be one of the most rewarding jobs in Scouting. As we reach Scouting's centennial, the Commissioner position is getting renewed emphasis and exposure. Funding for non-profits is getting harder to come by resulting in less growth of the professional staffs. The need for more volunteer Commissioners is as great or greater than any time in the past Our role in Scouting will continue to be fundamentally important for the next 100 years. As Commissioners, we must make sure that every unit is offering their boys exactly what is promised to them …, fun, excitement, adventure, and ultimately a quality experience. The Roots of Commissioner Service As Commissioners in the Boy Scouts of America, we are delegated authority and responsibility from the National Council through our "Commission" per the By Laws of the National Council. -

Southwick Village News

Southwick Village News A bi-monthly publication by Southwick Parish Council Issue 51 August 2017 Attractions include Village organisations and Local Services Southwick Parish Council has eleven elected members and meets on the third Tuesday each month in the village hall. Council meetings are open to the public and copies of the minutes may be seen on both PC notice boards, one situated by Organisation Telephone Number the bus stop outside Teeside and the other at the entrance road to the village hall. Wiltshire Council, Customer Services 0300 456 0100 WC All Planning Matters 0300 456 0100 Members of the Parish Council WC Highways & Street Lighting 0300 456 0105 Chair: Mr. D.J. Jackson Mutton Marsh Farm, Southwick, BA14 9PE 07837 154517 WC Dog Warden 0300 456 0107 Vice chair Mrs. K. Noble 230 Chantry Gardens, Southwick, BA14 9QX 01225 352503 WC Trading Standards 0845 404 0506 Trowbridge Town Council 01225 765072 Parish Clerk Mr. P. White 14 Brookmead, Southwick BA14 9QJ 01225 768241 Police (non emergency) 101 Mr. S.D. Carey Longfield, Frome Road, Southwick, BA14 9NJ 01225 764210 Police & fire emergency 999 Mr. G.E. Clayton 5 Blind Lane, Southwick, BA14 9PQ 01225 762447 Fire service Trowbridge (non emergency) 01225 756530 Mrs. T.J. Curry Bramley Cottage, 26 Blind Lane, Southwick, BA14 9PG 07771807080 Fire & Rescue safety checks 01380 723601 Mr. J. Eaton 30 Blind Lane, Southwick, BA14 9PG 07818870098 Selwood Housing 01225 715715 Mrs. J.C. Jones 28 Blind Lane, Southwick, BA14 9PG 01225 764223 Crimestoppers 0800 555111 Mr. F. Moreland Dead Maids Close, Chapmanslade, Westbury, BA13 4AD 07981 948348 National Benefit Fraud Team 0800 854440 Mr. -

Adult Leader Application

Jamboree 2021 Adult Leadership Application 2021 National Scout Jamboree Baltimore Area Council Contingent July 14-30, 2021 Adult Leader Application This is a fill-able PDF form. Please type in, or print very neatly. Email completed application to Baltimore Area Council at [email protected] Jamboree Adult Leader Qualifications Must have experience as a registered Scoutmaster, Assistant Scoutmaster, or Venturing Advisor or Assoc. Advisor for at least one year. Have a firm understanding of the "Patrol Method" and be able to implement it. Be a positive role model for Scouts and other adult leaders. Be able to attend all scheduled Jamboree Contingent meetings and Jamboree Troop meetings. Be able to attend the entire Jamboree experience with the Contingent. Be current in Youth Protection Training and be trained for your position in Scouting. Must complete an interview conducted by the Baltimore Area Council Jamboree Committee. Must be currently registered in the Baltimore Area Council and approved by the Baltimore Area Council's Scout Executive. Must meet all physical qualifications set by the National Scout Jamboree and have a completed Annual Health & Medical Record. If you have any questions or comments on applying, please contact the Baltimore Area Council at [email protected] Full name ________________________________________________________ Date of Birth ______________________________ Cell Phone _____________________ Home Phone _____________________ Occupation ___________________________________ Scout -

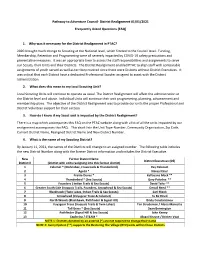

District Realignment 01/01/2021

Pathway to Adventure Council- District Realignment 01/01/2021 Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) 1. Why was it necessary for the District Realignment in PTAC? 2020 brought much change to Scouting at the National level, which filtered to the Council level. Funding, Membership, Retention and Programming were all severely impacted by COVID-19 safety precautions and preventative measures. It was an appropriate time to assess the staff responsibilities and assignments to serve our Scouts, their Units and their Districts. The District Realignment enabled PTAC to align staff with comparable assignments of youth served as well as territory covered since there were Districts without District Executives. It was critical that each District have a dedicated Professional Scouter assigned to assist with the District administration. 2. What does this mean to my local Scouting Unit? Local Scouting Units will continue to operate as usual. The District Realignment will affect the administration at the District level and above. Individual Units will continue their unit programming, planning, advancement and membership plans. The objective of the District Realignment was to provide our units the proper Professional and District Volunteer support for their success. 3. How do I know if my Scout unit is impacted by the District Realignment? There is a map which accompanies this FAQ on the PTAC website along with a list of all the units impacted by our realignment accompanies this FAQ. This chart lists the Unit Type-Number, Community Organization, Zip Code, Current District Name, Realigned District Name and New District Number. 4. What is the name of my Scouting District? By January 11, 2021, the names of the Districts will change to an assigned number. -

The Patriot Press

The Patriot Press http://www.ncacbsa.org/patriot/press Volume 19 February 2016 Issue 02 Patriot District National Capital Area Council Boy Scouts of America Patriot District Pinewood Derby It’s Cub Scout Pinewood Derby season again, and most Cub Scout Packs in the Patriot District have once again been busy preparing their cars, holding their individual racing and show events, and getting ready for the annual District Pinewood Derby. The 2016 District extravaganza will be held on Saturday, March 5, at Living Savior Lutheran Church located at 5500 Ox Rd (Route 123) in Fairfax Station. Each Pack in the Patriot District is invited to register one Cub Scout in each of five rank categories, and in one of two event categories, that will enable their participation in either the Speed or Show competitions. Thus, up to 10 Cub Scouts per pack are invited and permitted to participate. The District Pinewood Derby is not an open event and all participants must be pre-registered by their Pack Committee. The registration fee for each participating Cub Scout is $10.00. A document containing the rules for 2016 and providing much additional information has recently been distributed to Pack leaders. The rules for 2016 are essentially unchanged from last year. If you have any questions, please contact Pete Griffiths, District Pinewood Derby chair, at (571) 424-0022, [email protected] . Information regarding this event can also be found on the Patriot District website: http://www.ncacbsa.org/Patriot/PinewoodDerby Registration and competition times for each of the six Cub Scout (Rank/Den) categories are given in the table below. -

Rover Handbook

BPSA ROVER HANDBOOK This training manual is for use by B-P Service Association, US. This manual may be photocopied for Traditional Scouting purposes. Issued by order of the Baden-Powell Service Association (BPSA), US Headquarters Council. 1st Edition – 2013 Revision 4.5: July 2014 Document compiled and organized by Scott Moore from the original Scouting for Boys and Rovering to Success by Lord Baden-Powell, the BPSA Pathfinder Handbook compiled by David Atchley, the Traditional Rover Scout Handbook compiled by BPSA – British Columbia, the Boy Scouts Association 1938 edition of Policy, Organisation and Rules, and other Traditional Scouting material and resources, including information from the Red Cross. Special thanks to The Dump (TheDump.ScoutsCan.com) and Inquiry.net for providing access to many of these Scouting resources. Editors/Reviewers: Scott Moore, David Atchley, Scott Hudson, Jeff Kopp, Sue Pesznecker. The BPSA would like to thank those Scouters and volunteers who spent time reviewing the handbook and submitted edits, changes, and/or revisions. Their help has improved this handbook immensely. 2 Group, Crew, & Community Information To be filled in by the Rover. Name ______________________________________________________________________________________ Address & Phone # ___________________________________________________________________________ State/District ________________________________________________________________________________ Date of Birth ________________________________________________________________________________ -

DEVELOPMENT PLANNING TOOLKIT Scout District

Scout District Development Planning Toolkit 1 Scout District DEVELOPMENT PLANNING TOOLKIT This Scout District Development Planning Toolkit is one BE SMART of nine planning aids for use across the movement, to help members analyse the past and plan for the future. Before we look at how to put a development plan together, These documents comprise and replace all previous red, let’s ensure the targets we set are as realistic as possible; this amber, green (RAG) packs. While anyone may use these makes the whole process much easier in the long term. Make documents, it may be helpful to enlist the support of the your targets specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time- SHQ Programme and Development staff. bound (SMART). For example: Completing electronically We need a new Assistant District Commissioner The SWOT analysis, RAG reviews, planning matrix and development plan are set up so that you can complete them on your computer using Adobe Reader. Simply click in the box you S We will recruit one new adult for the district wish to complete and start typing. To download this for free click here. When their PVG is returned and they have received M their appointment, the target is reached Printing If you would prefer to print the whole document and complete This task is linked to the movement’s national it on paper, we recommend you print to A4. You may wish A objective to grow the number of adults to print and use only certain parts of this document. You can specify what pages you want to print from the print menu, and The new adult will help us meet the future demand the relevant parts can be found on the following pages: R of young people, identified by the waiting list • SWOT analysis page 3 We will run this task for eight weeks, with a deadline • RAG reviews pages 4 – 11 T • Planning matrix page 12 of xx/xx/xxxx • Blank development plan page 14 If you use this system for setting targets, you are far more likely to succeed. -

Once a Scout Always a Scout ______

Downloaded from: “The Dump” at Scoutscan.com http://www.thedump.scoutscan.com/ Editor’s Note: The reader is reminded that these texts have been written a long time ago. Consequently, they may use some terms or use expressions which were current at the time, regardless of what we may think of them at the beginning of the 21st century. For reasons of historical accuracy they have been preserved in their original form. If you find them offensive, we ask you to please delete this file from your system. This and other traditional Scouting texts may be downloaded from the Dump. ROVERING PROVISIONAL OUTLINE _______ First Printed March, 1930. Revised December, 1930. For further copies apply to your Boy Scout Council Headquarters or if you can- Not obtain them there write to ROBERT S. HALE 939 Boylston Street, Bolton Price 25 cents each or $2.00 in lots of 10. Once A Scout Always A Scout __________________________________________ FORWARD PROVISIONAL OUTLINE _______ (i) The words of the SCOUT promise are not the same for each language or nation, but the essence* is That on his honour he will do his best To do his duty, To help other people, To follow the Scout Law, and it is hoped that he will do this, not only while a boy, but all of his life. Rovering is for older Scouts, young men and older men; and Rover Crews, except for such cases as a University Crew, are usually part of Scout Groups, almost like graduate students still at their university. This pamphlet describes part of what is being done in New England.