Social Media Interactions and Chinese Identities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Energy in China: Coping with Increasing Demand

FOI-R--1435--SE November 2004 FOI ISSN 1650-1942 SWEDISH DEFENCE RESEARCH AGENCY User report Kristina Sandklef Energy in China: Coping with increasing demand Defence Analysis SE-172 90 Stockholm FOI-R--1435--SE November 2004 ISSN 1650-1942 User report Kristina Sandklef Energy in China: Coping with increasing demand Defence Analysis SE-172 90 Stockholm SWEDISH DEFENCE RESEARCH AGENCY FOI-R--1435--SE Defence Analysis November 2004 SE-172 90 Stockholm ISSN 1650-1942 User report Kristina Sandklef Energy in China: Coping with increasing demand Issuing organization Report number, ISRN Report type FOI – Swedish Defence Research Agency FOI-R--1435--SE User report Defence Analysis Research area code SE-172 90 Stockholm 1. Security, safety and vulnerability Month year Project no. November 2004 A 1104 Sub area code 11 Policy Support to the Government (Defence) Sub area code 2 Author/s (editor/s) Project manager Kristina Sandklef Ingolf Kiesow Approved by Maria Hedvall Sponsoring agency Department of Defense Scientifically and technically responsible Report title Energy in China: Coping with increasing demand Abstract (not more than 200 words) Sustaining the increasing energy consumption is crucial to future economic growth in China. This report focuses on the current and future situation of energy production and consumption in China and how China is coping with its increasing domestic energy demand. Today, coal is the most important energy resource, followed by oil and hydropower. Most energy resources are located in the inland, whereas the main demand for energy is in the coastal areas, which makes transportation and transmission of energy vital. The industrial sector is the main driver of the energy consumption in China, but the transport sector and the residential sector will increase their share of consumption by 2020. -

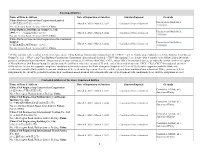

Sanctioned Entities Name of Firm & Address Date

Sanctioned Entities Name of Firm & Address Date of Imposition of Sanction Sanction Imposed Grounds China Railway Construction Corporation Limited Procurement Guidelines, (中国铁建股份有限公司)*38 March 4, 2020 - March 3, 2022 Conditional Non-debarment 1.16(a)(ii) No. 40, Fuxing Road, Beijing 100855, China China Railway 23rd Bureau Group Co., Ltd. Procurement Guidelines, (中铁二十三局集团有限公司)*38 March 4, 2020 - March 3, 2022 Conditional Non-debarment 1.16(a)(ii) No. 40, Fuxing Road, Beijing 100855, China China Railway Construction Corporation (International) Limited Procurement Guidelines, March 4, 2020 - March 3, 2022 Conditional Non-debarment (中国铁建国际集团有限公司)*38 1.16(a)(ii) No. 40, Fuxing Road, Beijing 100855, China *38 This sanction is the result of a Settlement Agreement. China Railway Construction Corporation Ltd. (“CRCC”) and its wholly-owned subsidiaries, China Railway 23rd Bureau Group Co., Ltd. (“CR23”) and China Railway Construction Corporation (International) Limited (“CRCC International”), are debarred for 9 months, to be followed by a 24- month period of conditional non-debarment. This period of sanction extends to all affiliates that CRCC, CR23, and/or CRCC International directly or indirectly control, with the exception of China Railway 20th Bureau Group Co. and its controlled affiliates, which are exempted. If, at the end of the period of sanction, CRCC, CR23, CRCC International, and their affiliates have (a) met the corporate compliance conditions to the satisfaction of the Bank’s Integrity Compliance Officer (ICO); (b) fully cooperated with the Bank; and (c) otherwise complied fully with the terms and conditions of the Settlement Agreement, then they will be released from conditional non-debarment. If they do not meet these obligations by the end of the period of sanction, their conditional non-debarment will automatically convert to debarment with conditional release until the obligations are met. -

China-Southeast Asia Relations: Trends, Issues, and Implications for the United States

Order Code RL32688 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web China-Southeast Asia Relations: Trends, Issues, and Implications for the United States Updated April 4, 2006 Bruce Vaughn (Coordinator) Analyst in Southeast and South Asian Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Wayne M. Morrison Specialist in International Trade and Finance Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress China-Southeast Asia Relations: Trends, Issues, and Implications for the United States Summary Southeast Asia has been considered by some to be a region of relatively low priority in U.S. foreign and security policy. The war against terror has changed that and brought renewed U.S. attention to Southeast Asia, especially to countries afflicted by Islamic radicalism. To some, this renewed focus, driven by the war against terror, has come at the expense of attention to other key regional issues such as China’s rapidly expanding engagement with the region. Some fear that rising Chinese influence in Southeast Asia has come at the expense of U.S. ties with the region, while others view Beijing’s increasing regional influence as largely a natural consequence of China’s economic dynamism. China’s developing relationship with Southeast Asia is undergoing a significant shift. This will likely have implications for United States’ interests in the region. While the United States has been focused on Iraq and Afghanistan, China has been evolving its external engagement with its neighbors, particularly in Southeast Asia. In the 1990s, China was perceived as a threat to its Southeast Asian neighbors in part due to its conflicting territorial claims over the South China Sea and past support of communist insurgency. -

Dramatic Decline of Wild South China Tigers Panthera Tigris Amoyensis: field Survey of Priority Tiger Reserves

Oryx Vol 38 No 1 January 2004 Dramatic decline of wild South China tigers Panthera tigris amoyensis: field survey of priority tiger reserves Ronald Tilson, Hu Defu, Jeff Muntifering and Philip J. Nyhus Abstract This paper describes results of a Sino- tree farms and other habitat conversion is common, and American field survey seeking evidence of South China people and their livestock dominate these fragments. While tigers Panthera tigris amoyensis in the wild. In 2001 and our survey may not have been exhaustive, and there may 2002 field surveys were conducted in eight reserves in be a single tiger or a few isolated tigers still remaining at five provinces identified by government authorities as sites we missed, our results strongly indicate that no habitat most likely to contain tigers. The surveys evaluated remaining viable populations of South China tigers occur and documented evidence for the presence of tigers, tiger within its historical range. We conclude that continued prey and habitat disturbance. Approximately 290 km of field eCorts are needed to ascertain whether any wild mountain trails were evaluated. Infrared remote cameras tigers may yet persist, concurrent with the need to con- set up in two reserves captured 400 trap days of data. sider options for the eventual recovery and restoration Thirty formal and numerous informal interviews were of wild tiger populations from existing captive populations. conducted with villagers to document wildlife knowledge, livestock management practices, and local land and Keywords Extinction, Panthera tigris amoyensis, resource use. We found no evidence of wild South China restoration, South China tiger. tigers, few prey species, and no livestock depredation by tigers reported in the last 10 years. -

Animal Welfare Consciousness of Chinese College Students: Findings and Analysis

WellBeing International WBI Studies Repository 3-2005 Animal Welfare Consciousness of Chinese College Students: Findings and Analysis Zu Shuxian Anhui Medical University Peter J. Li University of Houston-Downtown Pei-Feng Su Independent Animal Welfare Consultant Follow this and additional works at: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/socatani Recommended Citation Shuxian, Z., Li, P. J., & Su, P. F. (2005). Animal welfare consciousness of Chinese college students: findings and analysis. China Information, 19(1), 67-95. This material is brought to you for free and open access by WellBeing International. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Animal Welfare Consciousness of Chinese College Students: Findings and Analysis Zu Shuxian1, Peter J. Li2, and Pei-Feng Su3 1 Anhui Medical University 2 University of Houston-Downtown 3 Independent Animal Welfare Consultant KEYWORDS college students, cultural change, animal welfare consciousness ABSTRACT The moral character of China’s single-child generation has been studied by Chinese researchers since the early 1990s. Recent acts of animal cruelty by college students turned this subject of academic inquiry into a topic of public debate. This study joins the inquiry by asking if the perceived unique traits of the single-child generation, i.e. self- centeredness, lack of compassion, and indifference to the feelings of others, are discernible in their attitudes toward animals. Specifically, the study investigates whether the college students are in favor of better treatment of animals, objects of unprecedented exploitation on the Chinese mainland. With the help of two surveys conducted in selected Chinese universities, this study concludes that the college students, a majority of whom belong to the single-child generation, are not morally compromised. -

Regional Inequality in China's Health Care Expenditures

HEALTH ECONOMICS Health Econ. 18: S137–S146 (2009) Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI: 10.1002/hec.1511 REGIONAL INEQUALITY IN CHINA’S HEALTH CARE EXPENDITURES WIN LIN CHOUa,Ã and ZIJUN WANGb aDepartment of Economics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong and National Chiao Tung University, Taiwan bPrivate Enterprise Research Center, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA SUMMARY This paper has two parts. The first part examines the regional health expenditure inequality in China by testing two hypotheses on health expenditure convergence. Cross-section regressions and cluster analysis are used to study the health expenditure convergence and to identify convergence clusters. We find no single nationwide convergence, only convergence by cluster. In the second part of the paper, we investigate the long-run relationship between health expenditure inequality, income inequality, and provincial government budget deficits (BD) by using new panel cointegration tests with health expenditure data in China’s urban and rural areas. We find that the income inequality and real provincial government BD are useful in explaining the disparity in health expenditure prevailing between urban and rural areas. In order to reduce health-spending inequality, one long-run policy suggestion from our findings is for the government to implement more rapid economic development and stronger financing schemes in poorer rural areas. Copyright r 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. JEL classification: C2; C3; I10 KEY WORDS: health expenditure inequality; income inequality; government budget deficits; convergence test; panel cointegration test 1. INTRODUCTION An important feature of China’s economic reforms which began in 1978 is the dramatic change in its health system from a centrally planned system to a market-based one (Ma et al., 2008). -

Dramatic Decline of Wild South China Tigers Panthera Tigris Amoyensis: Field Survey of Priority Tiger Reserves

Colby College Digital Commons @ Colby Faculty Scholarship 1-1-2004 Dramatic decline of wild South China tigers Panthera tigris amoyensis: field survey of priority tiger reserves Ronald Tilson Hu Defu Jeff Muntifering Philip J. Nyhus Colby College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Tilson, Ronald; Defu, Hu; Muntifering, Jeff; and Nyhus, Philip J., "Dramatic decline of wild South China tigers Panthera tigris amoyensis: field survey of priority tiger reserves" (2004). Faculty Scholarship. 10. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/faculty_scholarship/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Colby. Oryx Vol 38 No 1 January 2004 Dramatic decline of wild South China tigers Panthera tigris amoyensis: field survey of priority tiger reserves Ronald Tilson, Hu Defu, Jeff Muntifering and Philip J. Nyhus Abstract This paper describes results of a Sino- tree farms and other habitat conversion is common, and American field survey seeking evidence of South China people and their livestock dominate these fragments. While tigers Panthera tigris amoyensis in the wild. In 2001 and our survey may not have been exhaustive, and there may 2002 field surveys were conducted in eight reserves in be a single tiger or a few isolated tigers still remaining at five provinces identified by government authorities as sites we missed, our results strongly indicate that no habitat most likely to contain tigers. -

An Empirical Account of Defamation Litigation in China

Columbia Law School Scholarship Archive Faculty Scholarship Faculty Publications 2006 Innovation through Intimidation: An Empirical Account of Defamation Litigation in China Benjamin L. Liebman Columbia Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Benjamin L. Liebman, Innovation through Intimidation: An Empirical Account of Defamation Litigation in China, 47 HARV. INT'L L. J. 33 (2006). Available at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/554 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarship Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOLUME 47, NUMBER 1, WINTER 2006 Innovation Through Intimidation: An Empirical Account of Defamation Litigation in China Benjamin L. Liebman* INTRODUCTION Consider two recent defamation cases in Chinese courts. In 2004, Zhang Xide, a former county-level Communist Party boss, sued the authors of a best selling book, An Investigation into China's Peasants. The book exposed official malfeasance on Zhang's watch and the resultant peasant hardships. Zhang demanded an apology from the book's authors and publisher, excision of the offending chapter, 200,000 yuan (approximately U.S.$25,000)' for emotional damages, and a share of profits from sales of the book. Zhang sued 2 in a local court on which, not coincidentally, his son sat as a judge. * Associate Professor of Law and Director, Center for Chinese Legal Studies, Columbia Law School. -

Chinese Tourists Shopping Behaviour in New Zealand: the Case of Health

CHINESE TOURISTS SHOPPING BEHAVIOUR IN NEW ZEALAND: THE CASE OF HEALTH AND BEAUTY PRODUCTS A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Commerce in Marketing Department of Management, Marketing, and Entrepreneurship Edward Paul Commons University of Canterbury June 2018 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Without doubt, this has been one of the toughest challenges that I have completed in my life. I would not have been able to achieve this without the ongoing support and guidance from several people, who have played their part in making this thesis possible. First, I would like to thank my supervisors, Associate Professor Girish Prayag and Dr Chris Chen. This project would not have been achievable without your support, guidance and belief in me that I could complete this. So, THANK YOU! To the MCom classes of 2016/17, this has been a journey that we have shared together. The constant support and encouragement that we have given each other has always been a great morale booster. Not to mention the BYO’s and other social occasions that we have enjoyed. Good luck with your future endeavours and I look forward to staying in touch and crossing paths on our future journeys. I would also like to extend my warmest of appreciation to those people close to me, my family and friends. To Henry and Thomas, cheers for everything that you have done the past few years to ensure I was getting my full share of laughs and enjoying life outside of my studies. Thanks to my partner Anita, for your constant encouragement, patience, and voluntary tasks that you have happily undertaken to make sure that my wellbeing and health remained intact. -

An Assessment of South China Tiger Reintroduction Potential in Hupingshan and Houhe National Nature Reserves, China ⇑ Yiyuan Qin A,B, Philip J

Biological Conservation 182 (2015) 72–86 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Biological Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon An assessment of South China tiger reintroduction potential in Hupingshan and Houhe National Nature Reserves, China ⇑ Yiyuan Qin a,b, Philip J. Nyhus a, , Courtney L. Larson a,g, Charles J.W. Carroll a,g, Jeff Muntifering c, Thomas D. Dahmer d, Lu Jun e, Ronald L. Tilson f a Environmental Studies Program, Colby College, Waterville, ME 04901, USA b Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, New Haven, CT, USA c Department of Conservation, Minnesota Zoo, 13000 Zoo Blvd., Apple Valley, MN 55124, USA d Ecosystems, Ltd., Unit B13, 12/F Block 2, Yautong Ind. City, 17 KoFai Road, Yau Tong, Kowloon, Hong Kong e National Wildlife Research and Development Center, State Forestry Administration, People’s Republic of China f Minnesota Zoo Foundation, 13000 Zoo Blvd., Apple Valley, MN 55124, USA g Graduate Degree Program in Ecology, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523, USA article info abstract Article history: Human-caused biodiversity loss is a global problem, large carnivores are particularly threatened, and the Received 11 June 2014 tiger (Panthera tigris) is among the world’s most endangered large carnivores. The South China tiger Received in revised form 20 October 2014 (Panthera tigris amoyensis) is the most critically endangered tiger subspecies and is considered function- Accepted 28 October 2014 ally extinct in the wild. The government of China has expressed its intent to reintroduce a small popula- Available online 12 December 2014 tion of South China tigers into a portion of their historic range as part of a larger goal to recover wild tiger populations in China. -

Copyright by Shaohua Guo 2012

Copyright by Shaohua Guo 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Shaohua Guo Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: THE EYES OF THE INTERNET: EMERGING TRENDS IN CONTEMPORARY CHINESE CULTURE Committee: Sung-Sheng Yvonne Chang, Supervisor Janet Staiger Madhavi Mallapragada Huaiyin Li Kirsten Cather THE EYES OF THE INTERNET: EMERGING TRENDS IN CONTEMPORARY CHINESE CULTURE by Shaohua Guo, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2012 Dedication To my grandparents, Guo Yimin and Zhang Huijun with love Acknowledgements During the outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in China in 2003, I, like many students in Beijing, was completely segregated from the outside world and confined on college campus for a couple of months. All activities on university campuses were called off. Students were assigned to designated dining halls, and were required to go to these places at scheduled times, to avoid all possible contagion of the disease. Surfing the Web, for the first time, became a legitimate “full-time job” for students. As was later acknowledged in the Chinese media, SARS cultivated a special emotional attachment to the Internet for a large number of the Chinese people, and I was one of them. Nine years later, my emotional ties to the Chinese Internet were fully developed into a dissertation, for which I am deeply indebted to my advisor Dr. Sung- Sheng Yvonne Chang. -

China: a Rich Flora Needed of Urgent Conservationprovided by Digital.CSIC

Orsis 19, 2004 49-89 View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE China: a rich flora needed of urgent conservationprovided by Digital.CSIC López-Pujol, Jordi GReB, Laboratori de Botànica, Facultat de Farmàcia, Universitat de Barcelona, Avda. Joan XXIII s/n, E-08028, Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain. Author for correspondence (E-mail: [email protected]) Zhao, A-Man Laboratory of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany, Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100093, The People’s Republic of China. Manuscript received in april 2004 Abstract China is one of the richest countries in plant biodiversity in the world. Besides to a rich flora, which contains about 33 000 vascular plants (being 30 000 of these angiosperms, 250 gymnosperms, and 2 600 pteridophytes), there is a extraordinary ecosystem diversity. In addition, China also contains a large pool of both wild and cultivated germplasm; one of the eight original centers of crop plants in the world was located there. China is also con- sidered one of the main centers of origin and diversification for seed plants on Earth, and it is specially profuse in phylogenetically primitive taxa and/or paleoendemics due to the glaciation refuge role played by this area in the Quaternary. The collision of Indian sub- continent enriched significantly the Chinese flora and produced the formation of many neoen- demisms. However, the distribution of the flora is uneven, and some local floristic hotspots can be found across China, such as Yunnan, Sichuan and Taiwan. Unfortunately, threats to this biodiversity are huge and have increased substantially in the last 50 years.