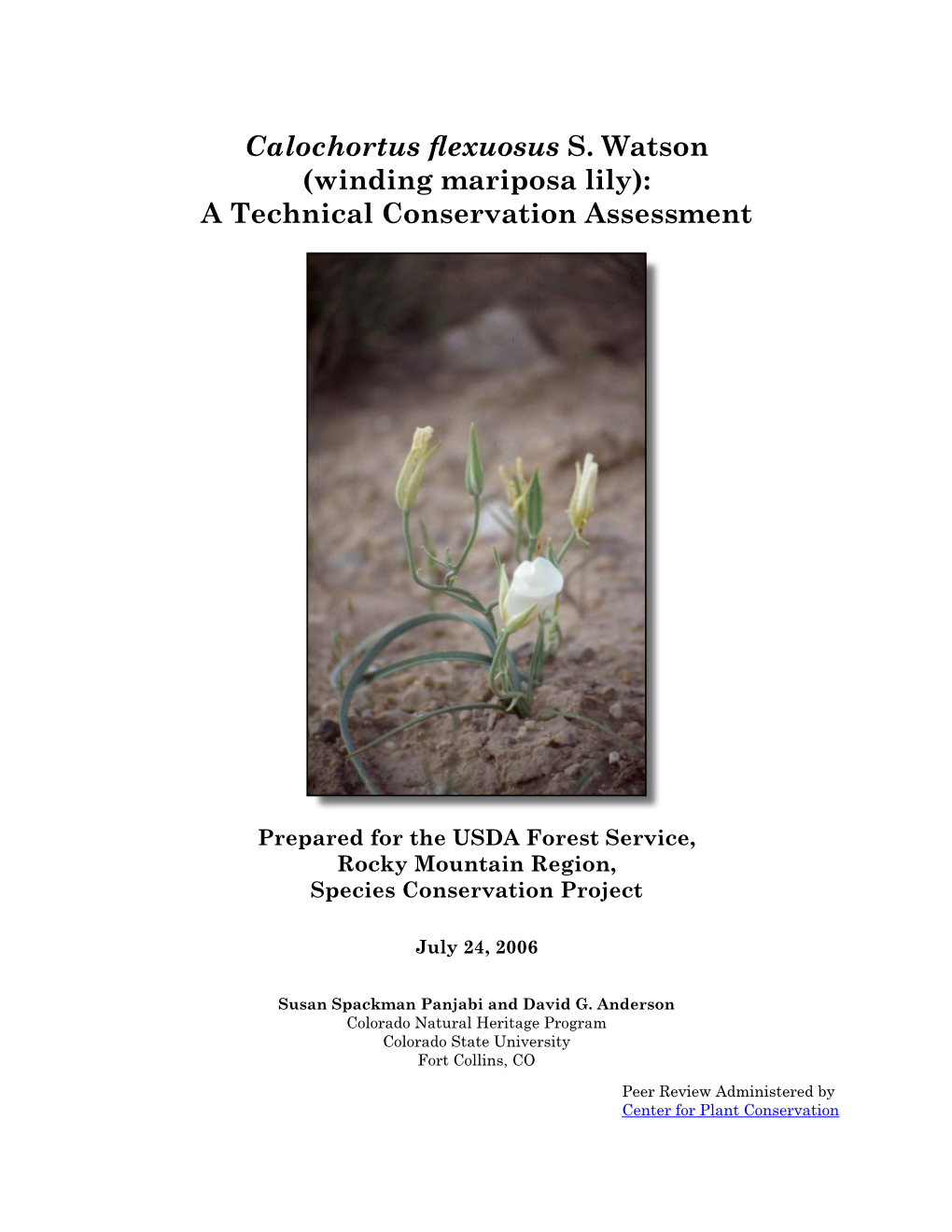

Calochortus Flexuosus S. Watson (Winding Mariposa Lily): a Technical Conservation Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summary of Offerings in the PBS Bulb Exchange, Dec 2012- Nov 2019

Summary of offerings in the PBS Bulb Exchange, Dec 2012- Nov 2019 3841 Number of items in BX 301 thru BX 463 1815 Number of unique text strings used as taxa 990 Taxa offered as bulbs 1056 Taxa offered as seeds 308 Number of genera This does not include the SXs. Top 20 Most Oft Listed: BULBS Times listed SEEDS Times listed Oxalis obtusa 53 Zephyranthes primulina 20 Oxalis flava 36 Rhodophiala bifida 14 Oxalis hirta 25 Habranthus tubispathus 13 Oxalis bowiei 22 Moraea villosa 13 Ferraria crispa 20 Veltheimia bracteata 13 Oxalis sp. 20 Clivia miniata 12 Oxalis purpurea 18 Zephyranthes drummondii 12 Lachenalia mutabilis 17 Zephyranthes reginae 11 Moraea sp. 17 Amaryllis belladonna 10 Amaryllis belladonna 14 Calochortus venustus 10 Oxalis luteola 14 Zephyranthes fosteri 10 Albuca sp. 13 Calochortus luteus 9 Moraea villosa 13 Crinum bulbispermum 9 Oxalis caprina 13 Habranthus robustus 9 Oxalis imbricata 12 Haemanthus albiflos 9 Oxalis namaquana 12 Nerine bowdenii 9 Oxalis engleriana 11 Cyclamen graecum 8 Oxalis melanosticta 'Ken Aslet'11 Fritillaria affinis 8 Moraea ciliata 10 Habranthus brachyandrus 8 Oxalis commutata 10 Zephyranthes 'Pink Beauty' 8 Summary of offerings in the PBS Bulb Exchange, Dec 2012- Nov 2019 Most taxa specify to species level. 34 taxa were listed as Genus sp. for bulbs 23 taxa were listed as Genus sp. for seeds 141 taxa were listed with quoted 'Variety' Top 20 Most often listed Genera BULBS SEEDS Genus N items BXs Genus N items BXs Oxalis 450 64 Zephyranthes 202 35 Lachenalia 125 47 Calochortus 94 15 Moraea 99 31 Moraea -

Sunol Wildflower Guide

Sunol Wildflowers A photographic guide to showy wildflowers of Sunol Regional Wilderness Sorted by Flower Color Photographs by Wilde Legard Botanist, East Bay Regional Park District Revision: February 23, 2007 More than 2,000 species of native and naturalized plants grow wild in the San Francisco Bay Area. Most are very difficult to identify without the help of good illustrations. This is designed to be a simple, color photo guide to help you identify some of these plants. The selection of showy wildflowers displayed in this guide is by no means complete. The intent is to expand the quality and quantity of photos over time. The revision date is shown on the cover and on the header of each photo page. A comprehensive plant list for this area (including the many species not found in this publication) can be downloaded at the East Bay Regional Park District’s wild plant download page at: http://www.ebparks.org. This guide is published electronically in Adobe Acrobat® format to accommodate these planned updates. You have permission to freely download and distribute, and print this pdf for individual use. You are not allowed to sell the electronic or printed versions. In this version of the guide, only showy wildflowers are included. These wildflowers are sorted first by flower color, then by plant family (similar flower types), and finally by scientific name within each family. Under each photograph are four lines of information, based on the current standard wild plant reference for California: The Jepson Manual: Higher Plants of California, 1993. Common Name These non-standard names are based on Jepson and other local references. -

View Plant List Here

11th annual Theodore Payne Native Plant Garden Tour planT list garden 2 in mid-city provided by homeowner Botanical Name Common Name Acalypha californica California Copperleaf Achillea millefolium Yarrow Achillea millefolium var rosea ‘Island Pink’ Island Pink Yarrow Adiantum jordanii California Maidenhair Fern Agave deserti Desert Agave Allium crispum Wild Onion Allium falcifolium Scythe Leaf Onion Allium haematochiton Red Skinned Onion Allium howellii var. clokeyi Mt. Pinos Onion Allium unifolium Single Leaf Onion Anemopsis californica Yerba Mansa Aquilegia formosa Western Columbine Arabis blepharophylla ‘Spring Charm’ Spring Charm Coast Rock Cress Arbutus menziesii Madrone Arctostaphylos ‘Baby Bear’ Baby Bear Manzanita Arctostaphylos ‘Emerald Carpet’ Emerald Carpet Manzanita Arctostaphylos ‘Howard McMinn’ Howard McMinn Manzanita Arctostaphylos bakeri ‘Louis Edmunds’ Louis Edmunds Manzanita Arctostaphylos densiflora ‘Sentinel’ Sentinel Manzanita Arctostaphylos glauca Big Berry Manzanita Arctostaphylos hookeri ‘Monterey Carpet’ Monterey Carpet Manzanita Arctostaphylos hookeri ‘Wayside’ Wayside Manzanita Arctostaphylos manzanita ‘Byrd Hill’ Byrd Hill Manzanita Arctostaphylos manzanita ‘Dr. Hurd’ Dr. Hurd Manzanita Arctostaphylos viscida Whiteleaf Manzanita Aristida purpurea Purple Three Awn Armeria maritima ‘Rubrifolia’ Rubrifolia Sea Thrift Artemisia californica California Sagebrush Artemisia californica ‘Canyon Grey’ Canyon Grey California Sagebrush Artemisia ludoviciana Silver Wormwood Artemisia pycnocephala ‘David’s Choice’ David’s -

Vascular Plants at Fort Ross State Historic Park

19005 Coast Highway One, Jenner, CA 95450 ■ 707.847.3437 ■ [email protected] ■ www.fortross.org Title: Vascular Plants at Fort Ross State Historic Park Author(s): Dorothy Scherer Published by: California Native Plant Society i Source: Fort Ross Conservancy Library URL: www.fortross.org Fort Ross Conservancy (FRC) asks that you acknowledge FRC as the source of the content; if you use material from FRC online, we request that you link directly to the URL provided. If you use the content offline, we ask that you credit the source as follows: “Courtesy of Fort Ross Conservancy, www.fortross.org.” Fort Ross Conservancy, a 501(c)(3) and California State Park cooperating association, connects people to the history and beauty of Fort Ross and Salt Point State Parks. © Fort Ross Conservancy, 19005 Coast Highway One, Jenner, CA 95450, 707-847-3437 .~ ) VASCULAR PLANTS of FORT ROSS STATE HISTORIC PARK SONOMA COUNTY A PLANT COMMUNITIES PROJECT DOROTHY KING YOUNG CHAPTER CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY DOROTHY SCHERER, CHAIRPERSON DECEMBER 30, 1999 ) Vascular Plants of Fort Ross State Historic Park August 18, 2000 Family Botanical Name Common Name Plant Habitat Listed/ Community Comments Ferns & Fern Allies: Azollaceae/Mosquito Fern Azo/la filiculoides Mosquito Fern wp Blechnaceae/Deer Fern Blechnum spicant Deer Fern RV mp,sp Woodwardia fimbriata Giant Chain Fern RV wp Oennstaedtiaceae/Bracken Fern Pleridium aquilinum var. pubescens Bracken, Brake CG,CC,CF mh T Oryopteridaceae/Wood Fern Athyrium filix-femina var. cyclosorum Western lady Fern RV sp,wp Dryopteris arguta Coastal Wood Fern OS op,st Dryopteris expansa Spreading Wood Fern RV sp,wp Polystichum munitum Western Sword Fern CF mh,mp Equisetaceae/Horsetail Equisetum arvense Common Horsetail RV ds,mp Equisetum hyemale ssp.affine Common Scouring Rush RV mp,sg Equisetum laevigatum Smooth Scouring Rush mp,sg Equisetum telmateia ssp. -

Zion National Park What's up and Blooming 2003

Zion National Park - What's Up and Blooming - 2003 Copyright 2000-2004 Margaret Malm I Zion National Park What's Up and Blooming 2003 Table of Contents Foreword 0 Part I Welcome 2 Part II April 4, 2003 2 Part III April 11, 2003 6 Part IV April 24, 2003 10 Part V May 3, 2003 15 Part VI May 18, 2003 19 Part VII May 23, 2003 23 Part VIII Pictures by color 29 1 White flowers... ................................................................................................................................ 29 2 Pink to red/red-violet............... .................................................................................................................... 30 3 Blue or purple.... ............................................................................................................................... 32 4 Yellow or orange........ ........................................................................................................................... 33 5 Variable colors..... .............................................................................................................................. 34 6 Trees/inconspicuous............... .................................................................................................................... 35 Copyright 2000-2004 Margaret Malm Welcome 2 1 Welcome Zion National Park What's up --and Blooming? 2003 We're having a really good flower bloom this year, at least so far. Finally got a little rain at just the right time. We'll need more, though, if the season is to contimue -

Redwood Wildflowers

Redwood Wildflowers A photographic guide to showy wildflowers of Redwood Regional Park Sorted by Flower Color Photographs by Wilde Legard Botanist, East Bay Regional Park District Revision: February 23, 2007 More than 2,000 species of native and naturalized plants grow wild in the San Francisco Bay Area. Most are very difficult to identify without the help of good illustrations. This is designed to be a simple, color photo guide to help you identify some of these plants. The selection of showy wildflowers displayed in this guide is by no means complete. The intent is to expand the quality and quantity of photos over time. The revision date is shown on the cover and on the header of each photo page. A comprehensive plant list for this area (including the many species not found in this publication) can be downloaded at the East Bay Regional Park District’s wild plant download page at: http://www.ebparks.org. This guide is published electronically in Adobe Acrobat® format to accommodate these planned updates. You have permission to freely download and distribute, and print this pdf for individual use. You are not allowed to sell the electronic or printed versions. In this version of the guide, only showy wildflowers are included. These wildflowers are sorted first by flower color, then by plant family (similar flower types), and finally by scientific name within each family. Under each photograph are four lines of information, based on the current standard wild plant reference for California: The Jepson Manual: Higher Plants of California, 1993. Common Name These non-standard names are based on Jepson and other local references. -

Distribution Patterns of Calochortus Greenii on the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument

Habitat and Landscape Distribution of Calochortus greenei S. Watson (Liliaceae) Across the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument, Southwest Oregon Evan Frost and Paul Hosten1 ABSTRACT The Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument includes a wide range of slope, elevation, soil types, and historic management activities. Calochortus greenei occupies a wide range of habitats primarily defined by topographic and edaphic factors. Several environmental factors are confounded with patterns of livestock use, making it difficult to separate the influence of individual factors. The inclusion of many environmental variables in multivariate models with little predictive power suggests that few generalizations about C. greenei abundance relative to environmental factors are valid across the larger landscape. Distance from vegetation edge was an important biotic variable incorporated in models of C. greenei population density across the landscape, suggesting that ecotones between soil types may play a role in defining suitable habitat. The varied localized influence of edaphic factors may indicate their indirect importance to C. greenei habitat by controlling the expression of mixed shrub and hardwood vegetation. Habitat analyses and examination of population size and change over time are similarly confounded by environmental and management factors. However, an examination within three areas of C. greenei aggregation with distinct soils and elevation indicate that the relative proportion of native perennial and non-native short-lived grasses are correlated with population size. These results suggest that invasive annual and short- lived perennial grasses may prevent the successful establishment and persistence of C. greenei seedlings, resulting in the long-term decline of populations in habitats and circumstances prone to invasion by ruderal species, including high livestock use areas. -

California Native Bulb Collection

U N I V E R S I T Y of C A L I F O R N I A NEWSLETTER Volume 23, Number 2 Published by the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA BOTANICAL GARDEN at Berkeley, California Spring 1998 California Native Bulb Collection arrangement of the California native area is Zigadenus (death camas). There is even a Calochortus The primarily by plant communities, with the named for Mr. Raiche, Calochortus raichei (Cedars fairy notable exception of the bulb display. There lantern). In addition to this nearly complete collection, are bulbs in the garden from many parts of the world, we have 417 accessions of native California bulbs but the collection of California native bulbs is by far the planted in other beds or in propagation in the nursery. most complete. Many of these are rare and/or endangered in This collection of California native bulb (and California, such as Brodiaea pallida, the Chinese Camp corm) plants has been in development for many brodiaea from the Sierra Nevada, where it grows on decades, but was not brought together into one private property and on adjacent land leased by the comparative planting until the 1960s by then-staff California Native Plant Society (CNPS). Additional member Wayne Roderick. The current “bulb bed” endangered taxa (as designated by CNPS) include display consists of two curved raised beds on the Oak Allium hoffmanii, Bloomeria humilis, Brodiaea coronaria ssp. Knoll in the northwest part of the Garden. This display, rosea, B. filifolia, B. insignis, B. kinkiensis, B. orcuttii, currently maintained by Roger Raiche and Shirley Calochortus obispoensis, C. -

Griffith Park Rare Plant Survey

Cooper Ecological Monitoring, Inc. EIN 72-1598095 Daniel S. Cooper, President 5850 W. 3rd St. #167 Los Angeles, CA 90036 (323) 397-3562 [email protected] Griffith Park Rare Plant Survey Plummer's mariposa-lily Calochortus plummerae (CNPS 1B.2) blooms near Skyline Trail in the northeastern corner of Griffith Park, 26 May 2010 (ph. DSC). Prepared by: Daniel S. Cooper Cooper Ecological Monitoring, Inc. October 2010 1 Part I. Summary of Findings Part II (species accounts) begins after p. 26. We present information on extant occurrences of 15 special-status species, subspecies and/or varieties of vascular plants in Griffith Park and contiguous open space, including three for which no known local specimen existed prior to this study: slender mariposa-lily (Calochortus clavatus var. gracilis; CNPS 1B.2), Humboldt lily (Lilium humboldtii var. ocellatum; CNPS 4.2), and Hubby's phacelia (Phacelia hubbyi; CNPS 4.2). Using lists developed by local botanists, we document - from specimens or digital photographs - extant occurrences of nearly 40 additional plant taxa felt to be of conservation concern in the eastern Santa Monica Mountains, including 16 for which no prior specimen existed for the park or surrounding open space. We also identify several dozen taxa known from the specimen record but unconfirmed in the park in recent years. From this information, we discuss patterns of occurrence of rare plants in the park, drawing attention to "hotspots" for rare species diversity, such as Spring Canyon and Royce Canyon, and identify areas, particularly in the northeastern corner of the park and along the southeastern border, where rare plants are relatively poorly represented in the landscape. -

USDA Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Region Sensitive Plant Species by Forest

USDA Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Region 1 Sensitive Plant Species by Forest 2013 FS R5 RF Plant Species List Klamath NF Mendocino NF Shasta-Trinity NF NF Rivers Six Lassen NF Modoc NF Plumas NF EldoradoNF Inyo NF LTBMU Tahoe NF Sequoia NF Sierra NF Stanislaus NF Angeles NF Cleveland NF Los Padres NF San Bernardino NF Scientific Name (Common Name) Abies bracteata (Santa Lucia fir) X Abronia alpina (alpine sand verbena) X Abronia nana ssp. covillei (Coville's dwarf abronia) X X Abronia villosa var. aurita (chaparral sand verbena) X X Acanthoscyphus parishii var. abramsii (Abrams' flowery puncturebract) X X Acanthoscyphus parishii var. cienegensis (Cienega Seca flowery puncturebract) X Agrostis hooveri (Hoover's bentgrass) X Allium hickmanii (Hickman's onion) X Allium howellii var. clokeyi (Mt. Pinos onion) X Allium jepsonii (Jepson's onion) X X Allium marvinii (Yucaipa onion) X Allium tribracteatum (three-bracted onion) X X Allium yosemitense (Yosemite onion) X X Anisocarpus scabridus (scabrid alpine tarplant) X X X Antennaria marginata (white-margined everlasting) X Antirrhinum subcordatum (dimorphic snapdragon) X Arabis rigidissima var. demota (Carson Range rock cress) X X Arctostaphylos cruzensis (Arroyo de la Cruz manzanita) X Arctostaphylos edmundsii (Little Sur manzanita) X Arctostaphylos glandulosa ssp. gabrielensis (San Gabriel manzanita) X X Arctostaphylos hooveri (Hoover's manzanita) X Arctostaphylos luciana (Santa Lucia manzanita) X Arctostaphylos nissenana (Nissenan manzanita) X X Arctostaphylos obispoensis (Bishop manzanita) X Arctostphylos parryana subsp. tumescens (interior manzanita) X X Arctostaphylos pilosula (Santa Margarita manzanita) X Arctostaphylos rainbowensis (rainbow manzanita) X Arctostaphylos refugioensis (Refugio manzanita) X Arenaria lanuginosa ssp. saxosa (rock sandwort) X Astragalus anxius (Ash Valley milk-vetch) X Astragalus bernardinus (San Bernardino milk-vetch) X Astragalus bicristatus (crested milk-vetch) X X Pacific Southwest Region, Regional Forester's Sensitive Species List. -

A Guide to Priority Plant and Animal Species in Oregon Forests

A GUIDE TO Priority Plant and Animal Species IN OREGON FORESTS A publication of the Oregon Forest Resources Institute Sponsors of the first animal and plant guidebooks included the Oregon Department of Forestry, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, the Oregon Biodiversity Information Center, Oregon State University and the Oregon State Implementation Committee, Sustainable Forestry Initiative. This update was made possible with help from the Northwest Habitat Institute, the Oregon Biodiversity Information Center, Institute for Natural Resources, Portland State University and Oregon State University. Acknowledgments: The Oregon Forest Resources Institute is grateful to the following contributors: Thomas O’Neil, Kathleen O’Neil, Malcolm Anderson and Jamie McFadden, Northwest Habitat Institute; the Integrated Habitat and Biodiversity Information System (IBIS), supported in part by the Northwest Power and Conservation Council and the Bonneville Power Administration under project #2003-072-00 and ESRI Conservation Program grants; Sue Vrilakas, Oregon Biodiversity Information Center, Institute for Natural Resources; and Dana Sanchez, Oregon State University, Mark Gourley, Starker Forests and Mike Rochelle, Weyerhaeuser Company. Edited by: Fran Cafferata Coe, Cafferata Consulting, LLC. Designed by: Sarah Craig, Word Jones © Copyright 2012 A Guide to Priority Plant and Animal Species in Oregon Forests Oregonians care about forest-dwelling wildlife and plants. This revised and updated publication is designed to assist forest landowners, land managers, students and educators in understanding how forests provide habitat for different wildlife and plant species. Keeping forestland in forestry is a great way to mitigate habitat loss resulting from development, mining and other non-forest uses. Through the use of specific forestry techniques, landowners can maintain, enhance and even create habitat for birds, mammals and amphibians while still managing lands for timber production. -

Western Riverside County Multiple Species Habitat Conservation Plan (MSHCP) Biological Monitoring Program Rare Plant Survey Repo

Western Riverside County Multiple Species Habitat Conservation Plan (MSHCP) Biological Monitoring Program Rare Plant Survey Report 2008 15 April 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................1 SURVEY GOALS: ...........................................................................................................................1 METHODS .......................................................................................................................................2 PROTOCOL DEVELOPMENT............................................................................................................2 PERSONNEL AND TRAINING...........................................................................................................2 SURVEY SITE SELECTION ..............................................................................................................3 SURVEY METHODS........................................................................................................................7 DATA ANALYSIS ...........................................................................................................................9 RESULTS .......................................................................................................................................11 ALLIUM MARVINII, YUCAIPA ONION..............................................................................................13 ALLIUM MUNZII, MUNZ’S ONION