Chapter 2: Markets and Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Principles of MICROECONOMICS an Open Text by Douglas Curtis and Ian Irvine

with Open Texts Principles of MICROECONOMICS an Open Text by Douglas Curtis and Ian Irvine VERSION 2017 – REVISION B ADAPTABLE | ACCESSIBLE | AFFORDABLE Creative Commons License (CC BY-NC-SA) advancing learning Champions of Access to Knowledge OPEN TEXT ONLINE ASSESSMENT All digital forms of access to our high- We have been developing superior on- quality open texts are entirely FREE! All line formative assessment for more than content is reviewed for excellence and is 15 years. Our questions are continuously wholly adaptable; custom editions are pro- adapted with the content and reviewed for duced by Lyryx for those adopting Lyryx as- quality and sound pedagogy. To enhance sessment. Access to the original source files learning, students receive immediate per- is also open to anyone! sonalized feedback. Student grade reports and performance statistics are also provided. SUPPORT INSTRUCTOR SUPPLEMENTS Access to our in-house support team is avail- Additional instructor resources are also able 7 days/week to provide prompt resolu- freely accessible. Product dependent, these tion to both student and instructor inquiries. supplements include: full sets of adaptable In addition, we work one-on-one with in- slides and lecture notes, solutions manuals, structors to provide a comprehensive sys- and multiple choice question banks with an tem, customized for their course. This can exam building tool. include adapting the text, managing multi- ple sections, and more! Contact Lyryx Today! [email protected] advancing learning Principles of Microeconomics an Open Text by Douglas Curtis and Ian Irvine Version 2017 — Revision B BE A CHAMPION OF OER! Contribute suggestions for improvements, new content, or errata: A new topic A new example An interesting new question Any other suggestions to improve the material Contact Lyryx at [email protected] with your ideas. -

Microeconomics III Oligopoly — Preface to Game Theory

Microeconomics III Oligopoly — prefacetogametheory (Mar 11, 2012) School of Economics The Interdisciplinary Center (IDC), Herzliya Oligopoly is a market in which only a few firms compete with one another, • and entry of new firmsisimpeded. The situation is known as the Cournot model after Antoine Augustin • Cournot, a French economist, philosopher and mathematician (1801-1877). In the basic example, a single good is produced by two firms (the industry • is a “duopoly”). Cournot’s oligopoly model (1838) — A single good is produced by two firms (the industry is a “duopoly”). — The cost for firm =1 2 for producing units of the good is given by (“unit cost” is constant equal to 0). — If the firms’ total output is = 1 + 2 then the market price is = − if and zero otherwise (linear inverse demand function). We ≥ also assume that . The inverse demand function P A P=A-Q A Q To find the Nash equilibria of the Cournot’s game, we can use the proce- dures based on the firms’ best response functions. But first we need the firms payoffs(profits): 1 = 1 11 − =( )1 11 − − =( 1 2)1 11 − − − =( 1 2 1)1 − − − and similarly, 2 =( 1 2 2)2 − − − Firm 1’s profit as a function of its output (given firm 2’s output) Profit 1 q'2 q2 q2 A c q A c q' Output 1 1 2 1 2 2 2 To find firm 1’s best response to any given output 2 of firm 2, we need to study firm 1’s profit as a function of its output 1 for given values of 2. -

ECON - Economics ECON - Economics

ECON - Economics ECON - Economics Global Citizenship Program ECON 3020 Intermediate Microeconomics (3) Knowledge Areas (....) This course covers advanced theory and applications in microeconomics. Topics include utility theory, consumer and ARTS Arts Appreciation firm choice, optimization, goods and services markets, resource GLBL Global Understanding markets, strategic behavior, and market equilibrium. Prerequisite: ECON 2000 and ECON 3000. PNW Physical & Natural World ECON 3030 Intermediate Macroeconomics (3) QL Quantitative Literacy This course covers advanced theory and applications in ROC Roots of Cultures macroeconomics. Topics include growth, determination of income, employment and output, aggregate demand and supply, the SSHB Social Systems & Human business cycle, monetary and fiscal policies, and international Behavior macroeconomic modeling. Prerequisite: ECON 2000 and ECON 3000. Global Citizenship Program ECON 3100 Issues in Economics (3) Skill Areas (....) Analyzes current economic issues in terms of historical CRI Critical Thinking background, present status, and possible solutions. May be repeated for credit if content differs. Prerequisite: ECON 2000. ETH Ethical Reasoning INTC Intercultural Competence ECON 3150 Digital Economy (3) Course Descriptions The digital economy has generated the creation of a large range OCOM Oral Communication of significant dedicated businesses. But, it has also forced WCOM Written Communication traditional businesses to revise their own approach and their own value chains. The pervasiveness can be observable in ** Course fulfills two skill areas commerce, marketing, distribution and sales, but also in supply logistics, energy management, finance and human resources. This class introduces the main actors, the ecosystem in which they operate, the new rules of this game, the impacts on existing ECON 2000 Survey of Economics (3) structures and the required expertise in those areas. -

Adam Smith 1723 – 1790 He Describes the General Harmony Of

Adam Smith 1723 – 1790 He describes the general harmony of human motives and activities under a beneficent Providence, and the general theme of “the invisible hand” promoting the harmony of interests. The invisible hand: There are two important features of Smith’s concept of the “invisible hand”. First, Smith was not advocating a social policy (that people should act in their own self interest), but rather was describing an observed economic reality (that people do act in their own interest). Second, Smith was not claiming that all self-interest has beneficial effects on the community. He did not argue that self-interest is always good; he merely argued against the view that self- interest is necessarily bad. It is worth noting that, upon his death, Smith left much of his personal wealth to churches and charities. On another level, though, the “invisible hand” refers to the ability of the market to correct for seemingly disastrous situations with no intervention on the part of government or other organizations (although Smith did not, himself, use the term with this meaning in mind). For example, Smith says, if a product shortage were to occur, that product’s price in the market would rise, creating incentive for its production and a reduction in its consumption, eventually curing the shortage. The increased competition among manufacturers and increased supply would also lower the price of the product to its production cost plus a small profit, the “natural price.” Smith believed that while human motives are often selfish and greedy, the competition in the free market would tend to benefit society as a whole anyway. -

1 Three Essential Questions of Production

Three Essential Questions of Production ~ Economic Understandings SS7E5a Name_______________________________________Date__________________________________ Class 1 2 3 4 Traditional Economies Command Economies Market Economies Mixed Economies What is In this type of In a command economy, the In a market economy, the Nearly all economies in produced? economic system, what central government decides wants of the consumers and the world today have is produced is based on what goods and services will the profit motive of the characteristics of both custom and the habit be produced, what wages will producers will decide what market and command of how such decisions be paid to workers, what will be produced. A.K.A. economic systems. were made in the past. jobs the workers do, as well Free-enterprise, Laisse- as the prices of goods. faire & capitalism. This means that most How is it The methods of In a command economy, no Labor (the workers) and countries have produced? production are one can start their own management (the characteristics of a primitive. Bartering, or business. bosses/owners) together free market/free a system of trading in The government determines will determine how goods enterprise as well as goods and services, how and where the goods will be produced in a market some government replaces currency in a produced would be sold. economy. planning and control. traditional economy. For whom is The primary group for In a command economy, the In a market economy, each it produced? whom goods and government determines how production resource is paid services are produced the goods and services are based on what is in a traditional economy distributed. -

FALL 2021 COURSE SCHEDULE August 23 –– December 9, 2021

9/15/21 DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS FALL 2021 COURSE SCHEDULE August 23 –– December 9, 2021 Course # Class # Units Course Title Day Time Location Instruction Mode Instructor Limit 1078-001 20457 3 Mathematical Tools for Economists 1 MWF 8:00-8:50 ECON 117 IN PERSON Bentz 47 1078-002 20200 3 Mathematical Tools for Economists 1 MWF 6:30-7:20 ECON 119 IN PERSON Hurt 47 1078-004 13409 3 Mathematical Tools for Economists 1 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Marein 71 1088-001 18745 3 Mathematical Tools for Economists 2 MWF 6:30-7:20 HLMS 141 IN PERSON Zhou, S 47 1088-002 20748 3 Mathematical Tools for Economists 2 MWF 8:00-8:50 HLMS 211 IN PERSON Flynn 47 2010-100 19679 4 Principles of Microeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Keller 500 2010-200 14353 4 Principles of Microeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Carballo 500 2010-300 14354 4 Principles of Microeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Bottan 500 2010-600 14355 4 Principles of Microeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Klein 200 2010-700 19138 4 Principles of Microeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Gruber 200 2020-100 14356 4 Principles of Macroeconomics 0 ONLINE ONLINE ONLINE Valkovci 400 3070-010 13420 4 Intermediate Microeconomic Theory MWF 9:10-10:00 ECON 119 IN PERSON Barham 47 3070-020 21070 4 Intermediate Microeconomic Theory TTH 2:20-3:35 ECON 117 IN PERSON Chen 47 3070-030 20758 4 Intermediate Microeconomic Theory TTH 11:10-12:25 ECON 119 IN PERSON Choi 47 3070-040 21443 4 Intermediate Microeconomic Theory MWF 1:50-2:40 ECON 119 IN PERSON Bottan 47 3080-001 22180 3 Intermediate Macroeconomic Theory MWF 11:30-12:20 -

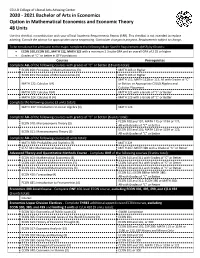

2020-2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical

CSULB College of Liberal Arts Advising Center 2020 - 2021 Bachelor of Arts in Economics Option in Mathematical Economics and Economic Theory 48 Units Use this checklist in combination with your official Academic Requirements Report (ARR). This checklist is not intended to replace advising. Consult the advisor for appropriate course sequencing. Curriculum changes in progress. Requirements subject to change. To be considered for admission to the major, complete the following Major Specific Requirements (MSR) by 60 units: • ECON 100, ECON 101, MATH 122, MATH 123 with a minimum 2.3 suite GPA and an overall GPA of 2.25 or higher • Grades of “C” or better in GE Foundations Courses Prerequisites Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (18 units total): ECON 100: Principles of Macroeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher ECON 101: Principles of Microeconomics (3) MATH 103 or Higher MATH 111; MATH 112B or 113; All with Grades of “C” MATH 122: Calculus I (4) or Better; or Appropriate CSULB Algebra and Calculus Placement MATH 123: Calculus II (4) MATH 122 with a Grade of “C” or Better MATH 224: Calculus III (4) MATH 123 with a Grade of “C” or Better Complete the following course (3 units total): MATH 247: Introduction to Linear Algebra (3) MATH 123 Complete ALL of the following courses with grades of “C” or better (6 units total): ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 310: Microeconomic Theory (3) All with Grades of “C” or Better ECON 100 and 101; MATH 115 or 119A or 122; ECON 311: Macroeconomic Theory (3) All with -

The Stock Market and the Economy

BARRY BOSWORTH Brookings Institution The Stock Market and the Economy THE STOCKMARKET decline of 1973-74 marked the longest and steepest fall in corporate-stockprices since the depressionof the 1930s.The loss of stockholderwealth in marketprices amounted to $525 billion, or 43 per- cent.'The magnitudeof this declinein stockvalues, in conjunctionwith the subsequentcollapse of aggregatedemand in 1974-75, has sparkeda re- newed discussionof the role of the stock marketin businesscycles. The debate-as is so frequentlythe case-is not new to economics.Several sig- nificantcontributions recently made at both the conceptualand empirical levels seem, however,to justify a reexaminationof the issues. The disputeabout the import of changesin the stock marketrevolves around their causal role in economicfluctuation: Are they a source of variationin aggregatedemand? Does the causationrun solely in the op- posite direction?Or do the levels of economicactivity and of stock prices simplyrespond similarly to other,more basic, economic forces, with no di- rect causal link betweenthe two? This third interpretationis consistent with a view that the stock marketreflects investors' attempts to forecast economictrends. The fact that movementsin stock prices foretellmajor Note: I am gratefulto LeonardHerk for researchaid in writingthis article.Members of the Brookingspanel offeredvaluable comments and suggestionsin the preparationof the draft. David A. Wyss of the Federal Reserve Board staff provided the computer simulationsof the MPS model and answerednumerous questions. 1. Derived as the change between December 1972 and December 1974, as shown in Board of Governorsof the FederalReserve System, unpublisheddetail accounts, from the flow of funds (July 1975). 257 258 BrookingsPapers on EconomicActivity, 2:1975 cyclesin businessactivity is, thus, only evidencethat investors'forecasts are betterthan randomguesses. -

Vanguard Economic and Market Outlook 2021: Approaching the Dawn

Vanguard economic and market outlook for 2021: Approaching the dawn Vanguard Research December 2020 ■ While the global economy continues to recover as we head into 2021, the battle between the virus and humanity’s efforts to stanch it continues. Our outlook for the global economy hinges critically on health outcomes. The recovery’s path is likely to prove uneven and varied across industries and countries, even with an effective vaccine in sight. ■ In China, we see the robust recovery extending in 2021 with growth of 9%. Elsewhere, we expect growth of 5% in the U.S. and 5% in the euro area, with those economies making meaningful progress toward full employment levels in 2021. In emerging markets, we expect a more uneven and challenging recovery, with growth of 6%. ■ When we peek beyond the long shadow of COVID-19, we see the pandemic irreversibly accelerating trends such as work automation and digitization of economies. However, other more profound setbacks brought about by the lockdowns and recession will ultimately prove temporary. Assuming a reasonable path for health outcomes, the scarring effect of permanent job losses is likely to be limited. ■ Our fair-value stock projections continue to reveal a global equity market that is neither grossly overvalued nor likely to produce outsized returns going forward. This suggests, however, that there may be opportunities to invest broadly around the world and across the value spectrum. Given a lower-for-longer rate outlook, we find it hard to see a material uptick in fixed income returns in the foreseeable future. Lead authors Vanguard Investment Strategy Group Vanguard Global Economics and Capital Markets Outlook Team Joseph Davis, Ph.D., Global Chief Economist Joseph Davis, Ph.D. -

Market Failure in Kidney Exchange†

American Economic Review 2019, 109(11): 4026–4070 https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20180771 Market Failure in Kidney Exchange† By Nikhil Agarwal, Itai Ashlagi, Eduardo Azevedo, Clayton R. Featherstone, and Ömer Karaduman* We show that kidney exchange markets suffer from market failures whose remedy could increase transplants by 30 to 63 percent. First, we document that the market is fragmented and inefficient; most trans- plants are arranged by hospitals instead of national platforms. Second, we propose a model to show two sources of inefficiency: hospitals only partly internalize their patients’ benefits from exchange, and current platforms suboptimally reward hospitals for submitting patients and donors. Third, we calibrate a production function and show that indi- vidual hospitals operate below efficient scale. Eliminating this ineffi- ciency requires either a mandate or a combination of new mechanisms and reimbursement reforms. JEL D24, D47, I11 ( ) The kidney exchange market in the United States enables approximately 800 transplants per year for kidney patients who have a willing but incompatible live donor. Exchanges are organized by matching these patient–donor pairs into swaps that enable transplants. Each such transplant extends and improves the patient’s quality of life and saves hundreds of thousands of dollars in medical costs, ulti- mately creating an economic value estimated at more than one million dollars.1 Since monetary compensation for living donors is forbidden and deceased donors * Agarwal: Department of Economics, MIT, -

The Profit Motive in Education: Continuing the Revolution the Profit Motive in Education: Continuing the Revolution

The Profit Motive in Education: Continuing the Revolution The Profit Motive in Education: Continuing the Revolution EDITED BY JAMES B. STANFIELD The Institute of Economic Affairs First published in Great Britain in 2012 by CONTENTS The Institute of Economic Affairs 2 Lord North Street Westminster London sw1p 3lb in association with Profile Books Ltd The authors 9 The mission of the Institute of Economic Affairs is to improve public understanding of the fundamental institutions of a free society, with particular Foreword 14 reference to the role of markets in solving economic and social problems. Summary 22 List of tables and figures 25 Copyright © The Institute of Economic Affairs 2012 The moral right of the author has been asserted. PART 1: BASIC CONCEPTS 1 Introduction 29 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, James B. Stanfield no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, Questioning the anti-profit mentality 29 mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written Things seen and not seen in education 34 permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. Policy lessons 38 Four simple policy proposals 41 A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. A vision of the liberal ideal of education 45 ISBN 978 0 255 36646 5 References 49 eISBN 978 0 255 36678 6 Many IEA publications are translated into languages other than English or 2 Profit is about learning, not just motivation 51 are reprinted. -

Power Market Economics LLC Evolving Capacity Markets in A

Power Market Economics LLC Evolving Capacity Markets in a Modern Grid By Robert Stoddard State policies in New England mandate substantial shifts in the generation resources serving their citizen’s electrical needs. Maine, for example, has a statutory requirement to shift to 80 percent renewables by 2030, with a goal of reaching 100 percent by 2050. Massachusetts’ Clean Energy Standard sets a minimum percentage of renewables at 16 percent in 2018, increasing 2 percentage points annually to 80 percent in 2050. Facing these sharp departures from business-as-usual, policymakers raise a core question: are today’s wholesale market designs able to help the states achieve these goals? Can they even accommodate these state policy resources? In particular, are today’s capacity markets—which are supposed to guide the long-term investment in electricity generation resources—up to the job? Capacity markets serve a central role in New England’s electricity market. They serve a critical role in helping to ensure that the system operator, ISO New England (ISO-NE), will have enough resources, located strategically on the grid, to meet expected peak loads with a sufficient reserve margin. How capacity markets are designed and operate has evolved relatively little since the New York Independent System Operator (NYISO) launched the first full-fledged capacity market in 1999, the primary innovations being a longer lead-time in procurement of resources, better to support the orderly exit and construction of resources, and higher performance requirements, better to ensure that resources being paid to be available are in fact operating when needed. Are capacity markets now irrelevant? No.