History of Maps a Map Is a Two-Dimensional Representation of a Portion of the Earth’S Surface

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

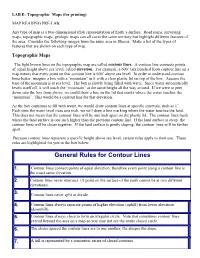

General Rules for Contour Lines

6/30/2015 EASC111LabEFor Printing LAB E: Topographic Maps (for printing) MAP READING PRELAB: Any type of map is a twodimensional (flat) representation of Earth’s surface. Road maps, surveying maps, topographic maps, geologic maps can all cover the same territory but highlight different features of the area. Consider the following images from the same area in Illinois. Make a list of the types of features that are shown on each type of map. Topographic Maps The light brown lines on the topographic map are called contour lines. A contour line connects points of equal height above sea level, called elevation. For example, a 600’ (six hundred foot) contour line on a map means that every point on that contour line is 600’ above sea level. In order to understand contour lines better, imagine a box with a “mountain” in it with a clear plastic lid on top of the box. Assume the base of the mountain is at sea level. The box is slowly being filled with water. Since water automatically levels itself off, it will touch the “mountain” at the same height all the way around. If we were to peer down into the box from above, we could draw a line on the lid that marks where the water touches the “mountain”. This would be a contour line for that elevation. As the box continues to fill with water, we would draw contour lines at specific intervals, such as 1”. Each time the water level rises one inch, we will draw a line marking where the water touches the land. -

Maps and Charts

Name:______________________________________ Maps and Charts Lab He had bought a large map representing the sea, without the least vestige of land And the crew were much pleased when they found it to be, a map they could all understand - Lewis Carroll, The Hunting of the Snark Map Projections: All maps and charts produce some degree of distortion when transferring the Earth's spherical surface to a flat piece of paper or computer screen. The ways that we deal with this distortion give us various types of map projections. Depending on the type of projection used, there may be distortion of distance, direction, shape and/or area. One type of projection may distort distances but correctly maintain directions, whereas another type may distort shape but maintain correct area. The type of information we need from a map determines which type of projection we might use. Below are two common projections among the many that exist. Can you tell what sort of distortion occurs with each projection? 1 Map Locations The latitude-longitude system is the standard system that we use to locate places on the Earth’s surface. The system uses a grid of intersecting east-west (latitude) and north-south (longitude) lines. Any point on Earth can be identified by the intersection of a line of latitude and a line of longitude. Lines of latitude: • also called “parallels” • equator = 0° latitude • increase N and S of the equator • range 0° to 90°N or 90°S Lines of longitude: • also called “meridians” • Prime Meridian = 0° longitude • increase E and W of the P.M. -

Topographic Maps Fields

Topographic Maps Fields • Field - any region of space that has some measurable value at every point. • Ex: temperature, air pressure, elevation, wind speed Isolines • Isolines- lines on a map that connect points of equal field value • Isotherms- lines of equal temperature • Isobars- lines of equal air pressure • Contour lines- lines of equal elevation Draw the isolines! (connect points of equal values) Isolines Drawn in Red Isotherm Map Isobar Map Topographic Maps • Topographic map (contour map)- shows the elevation field using contour lines • Elevation - the vertical height above & below sea level Why use sea level as a reference point? Topographic Maps Reading Contour lines Contour interval- the difference in elevation between consecutive contour lines Subtract the difference in value of two nearby contour lines and divide by the number of spaces between the contour lines Elevation – Elevation # spaces between 800- 700 =?? 5 Contour Interval = ??? Rules of Contour Lines • Never intersect, branch or cross • Always close on themselves (making circle) or go off the edge of the map • When crossing a stream, form V’s that point uphill (opposite to water flow) • Concentric circles mean the elevation is increasing toward the top of a hill, unless there are hachures showing a depression • Index contour- thicker, bolder contour lines on contour maps, usually every 5 th line • Benchmark - BMX or X shows where a metal marker is in the ground and labeled with an exact elevation ‘Hills’ & ‘Holes’ A depression on a contour map is shown by contour lines with small marks pointing toward the lowest point of the depression. The first contour line with the depression marks (hachures) and the contour line outside it have the same elevation. -

Gradual Generalization of Nautical Chart Contours with a B-Spline Snake Method

GRADUAL GENERALIZATION OF NAUTICAL CHART CONTOURS WITH A B-SPLINE SNAKE METHOD BY DANDAN MIAO BS in Geographic Information Systems, Wuhan University, 2009 THESIS Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Ocean Engineering September, 2014 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED © 2014 Dandan Miao This thesis has been examined and approved. Dr. Brian Calder, Associate Research Professor of Ocean Engineering Dr. Kurt Schwehr Affiliate Associate Professor of Ocean Engineering Dr. Steve Wineberg Lecturer, Mathematics and Statistics Date v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This study was sponsored by NOAA grant NA10NOS400007, and supported by the Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping. Professor Larry Mayer introduced me to the world of Ocean Mapping, and taught me new information about geological oceanography; Professor Brian Calder initiated this study and has always been able to selflessly help me with any questions; Professor Steven Wineberg gave me many insights of how to transfer math concepts to graphic behavior; Professor Kurt Schwehr helped me with many intelligent thoughts and suggestion about computer programming implementation. I am grateful for all their selfless help and patience, and I would like to thank all of them for their guidance, encouragement and proof-reading of this thesis: without them and CCOM’s support, this work would not have happened. Finally, I would like to thank my parents and friends, for encouragement and trust. Your love and faith gave me the strength to keep holding on and finally make it work! Love you all! With greatest thankfulness, Dandan Miao vi TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................................................................................. -

Creating a Contour Map of Your School Playground

How to Make a Contour Map of Your School Playground Source: Mountain Environments Novice On-Line Lessons http://www.math.montana.edu/~nmp/materials/ess/mountain_environments/ These instructions are for making a 4 x 4 contour map of a 6' x 6' plot of land. The number of contour intervals or size of the plot may be changed if desired. Step 1: To make a contour map, first stake out with string a plot of uneven land. Step 2: Determine the total change in elevation within your plot, from its highest point to its lowest point, in inches. (To measure this change in elevation you must place one end of a bubble stick level at the high point with the other end pointing towards the low point. Raise or lower the free end of the bubble stick until the bubble shows the stick is level.) With the yardstick, measure the vertical distance from the free end of the bubble stick to the ground. Continue measuring in this manner until you reach the low point and add up all of the vertical measurements that you took at the various points. This is your total change in elevation. Step 3: Divide this elevation change by 4 to determine the contour interval when you build 3 contour lines. (Suppose the change in elevation was 24 inches from high point to low point. If 3 contour lines are needed between the high and low point, you'd divide the 24" by 4—not 3. The contour interval would be 6 inches. ) Step 4: Now that you have a contour interval, you must locate one point for each contour line that will be the starting point for that line. -

Latitude-Longitude and Topographic Maps Reading Supplement

Latitude-Longitude and Topographic Maps Reading Supplement Latitude and Longitude A key geographical question throughout the human experience has been, "Where am I?" In classical Greece and China, attempts were made to create logical grid systems of the world to answer this question. The ancient Greek geographer Ptolemy created a grid system and listed the coordinates for places throughout the known world in his book Geography. But it wasn't until the middle ages that the latitude and longitude system was developed and implemented. This system is written in degrees, using the symbol °. Latitude When looking at a map, latitude lines run horizontally. Latitude lines are also known as parallels since they are parallel and are an equal distant from each other. Each degree of latitude is approximately 69 miles (111 km) apart; there is a variation due to the fact that the earth is not a perfect sphere but an oblate ellipsoid (slightly egg-shaped). To remember latitude, imagine them as the horizontal rungs of a ladder ("ladder-tude"). Degrees latitude are numbered from 0° to 90° north and south. Zero degrees is the equator, the imaginary line which divides our planet into the northern and southern hemispheres. 90° north is the North Pole and 90° south is the South Pole. Longitude The vertical longitude lines are also known as meridians. They converge at the poles and are widest at the equator (about 69 miles or 111 km apart). Zero degrees longitude is located at Greenwich, England (0°). The degrees continue 180° east and 180° west where they meet and form the International Date Line in the Pacific Ocean. -

Topographic Maps

Topographic Maps Say Thanks to the Authors Click http://www.ck12.org/saythanks (No sign in required) To access a customizable version of this book, as well as other interactive content, visit www.ck12.org CK-12 Foundation is a non-profit organization with a mission to reduce the cost of textbook materials for the K-12 market both in the U.S. and worldwide. Using an open-content, web-based collaborative model termed the FlexBook®, CK-12 intends to pioneer the generation and distribution of high-quality educational content that will serve both as core text as well as provide an adaptive environment for learning, powered through the FlexBook Platform®. Copyright © 2014 CK-12 Foundation, www.ck12.org The names “CK-12” and “CK12” and associated logos and the terms “FlexBook®” and “FlexBook Platform®” (collectively “CK-12 Marks”) are trademarks and service marks of CK-12 Foundation and are protected by federal, state, and international laws. Any form of reproduction of this book in any format or medium, in whole or in sections must include the referral attribution link http://www.ck12.org/saythanks (placed in a visible location) in addition to the following terms. Except as otherwise noted, all CK-12 Content (including CK-12 Curriculum Material) is made available to Users in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC 3.0) License (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc/3.0/), as amended and updated by Creative Com- mons from time to time (the “CC License”), which is incorporated herein by this reference. -

NOAA Nav-Cast Transcript Capt. Chris Van Westendorp and Colby Harmon

NOAA Nav-cast Transcript How to obtain NOAA ENC-based paper nautical charts after NOAA ends production of traditional paper charts Capt. Chris van Westendorp and Colby Harmon January 9, 2019, 2 p.m. (EST) Colby Harmon: [00:01] Welcome everyone to NOAA Nav-cast, our quarterly webinar series that highlights the tools and trends of NOAA navigation services. I am Colby Harmon, a cartographer and project manager with the Marine Chart Division of NOAA’s Office of Coast Survey. I am here today with NOAA Corps Captain Chris van Westendorp, Chief of Coast Survey’s Navigation Services Division. This afternoon, Chris will present an overview of NOAA’s program to gradually sunset the production of traditional paper nautical charts and discuss some improvements that are being made to NOAA’s premiers electronic navigational chart product. Then, I will walk through how to use the NOAA Custom Chart prototype. This application provides mariners, recreational boaters, and other chart users with a new, customizable type of paper chart. Capt. Chris van Westendorp: [00:53] Thanks Colby. With the advent of GPS and other technologies, marine navigation has advanced significantly over the past few decades. We see an increasing reliance on the NOAA electronic navigational chart – the ENC – as the primary product used for navigation and decreasing use of traditional raster chart products. That is, paper charts and raster charts which are digital images of paper charts stored as pixels. In November 2019, NOAA announced it is starting a five- year program to end all traditional paper and raster nautical chart production. -

Lab 1: Geologic Techniques: Maps, Aerial Photographs and LIDAR Imagery Introduction Geoscientists Utilize Many Different Techniques to Study the Earth

Lab 1: Geologic Techniques: Maps, Aerial Photographs and LIDAR Imagery Introduction Geoscientists utilize many different techniques to study the Earth. Many of these techniques do not always involve fieldwork or direct sampling of the earth’s surface. Before a geoscientist completes work in the field he/or she will often review maps or remote images to provide important information relevant to a given study area. For example, when a geoscientist is retained to assess landslide hazards for a proposed housing development located proximal to a steep bluff slope, he/or she would certainly want to review topographic maps, geologic substrate maps, and aerial photography prior to completing a field visit to the study area. Since topography and substrate geology play important roles in landslide processes, it is important for a geoscientist to review the slope conditions and the underlying substrate geology to better understand potential landslide hazards for a given study area. Aerial photography, or other remote imagery, may provide the geoscientist with important historical data, such as vegetation age structure or other evidence quantifying the frequency of landslide activity and related hillslope erosion. Geoscientists also utilize maps and remote imagery to record their field data so that it can be synthesized and interpreted within a spatial context and shared with other geoscientists or the general public. In today’s laboratory we will explore map-reading, aerial photo interpretation and remote sensing techniques that are utilized by geoscientists to study the geologic landscapes processes operating at its surface. Many of these techniques will be integrated into future laboratory exercises. History of Maps A map is a two-dimensional representation of a portion of the Earth’s surface. -

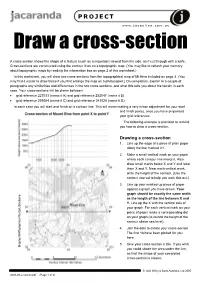

Draw a Cross-Section

PROJECT www.j aconline.com.au Draw a cross-section A cross-section shows the shape of a feature (such as a mountain) viewed from the side, as if cut through with a knife. Cross-sections are constructed using the contour lines on a topographic map. (You may like to refresh your memory about topographic maps by reading the information box on page 2 of this worksheet.) In this worksheet, you will draw two cross-sections from the topographical map of Mt Etna included on page 3. (You may find it easier to draw these if you first enlarge the map on a photocopier.) On completion, explain in a couple of paragraphs any similarities and differences in the two cross-sections, and what this tells you about the terrain in each case. Your cross-sections will be drawn between: • grid reference 227033 (name it A) and grid reference 252047 (name it B) • grid reference 239054 (name it C) and grid reference 241026 (name it D). In each case you will start and finish on a contour line. This will mean making a very minor adjustment for your start and finish points, once you have pinpointed your grid references. The following example is provided to remind you how to draw a cross-section. Drawing a cross-section 1. Line up the edge of a piece of plain paper along the line marked XY. 2. Make a small vertical mark on your paper where each contour line meets it. Also draw small marks below X and Y and label them X and Y. -

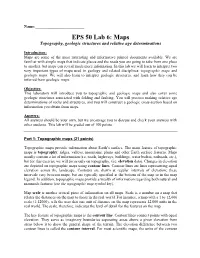

EPS 50 Lab 6: Maps Topography, Geologic Structures and Relative Age Determinations

Name:_________________________ EPS 50 Lab 6: Maps Topography, geologic structures and relative age determinations Introduction: Maps are some of the most interesting and informative printed documents available. We are familiar with simple maps that indicate places and the roads you are going to take from one place to another, but maps can reveal much more information. In this lab we will learn to interpret two very important types of maps used in geology and related disciplines: topographic maps and geologic maps. We will also learn to interpret geologic structures, and learn how they can be inferred from geologic maps. Objective: This laboratory will introduce you to topographic and geologic maps and also cover some geologic structures associated with folding and faulting. You will practice making relative age determinations of rocks and structures, and you will construct a geologic cross-section based on information you obtain from maps. Answers: All answers should be your own, but we encourage you to discuss and check your answers with other students. This lab will be graded out of 100 points. Part 1: Topographic maps (21 points) Topographic maps provide information about Earth’s surface. The main feature of topographic maps is topography: ridges, valleys, mountains, plains and other Earth surface features. Maps usually contain a lot of information (i.e. roads, highways, buildings, water bodies, railroads, etc.), but for this exercise we will focus only on topography, (i.e. elevation data). Changes in elevation are depicted on topographic maps using contour lines. Contour lines are lines representing equal elevation across the landscape. Contours are drawn at regular intervals of elevation; these intervals vary between maps, but are typically specified at the bottom of the map or in the map legend. -

Introduction to Topographic Maps Topographic Maps

Introduction to Topographic Maps Topographic Maps Topographic maps are two dimensional models of the Earth’s, which is considered three dimensional. Topographic maps are also known as contour maps. Topographic maps illustrate elevation above sea level using contour lines. Real World Contour Map Topographic Maps Contour Line A line on a map that connects points of equal elevation. These lines not only show elevation but also show the shape of the land. Topographic Maps Contour Interval This is the difference in elevation between each line. The spacing is 580 always equal. 560 540 This contour interval is 520 20 feet. Topographic Maps Index Contours These help the map reader determine elevation. Every fifth line is darker and has an elevation printed on it. Rules for Contours 1. Contour lines never cross each other. Rules for Contours 2. Contours always form closed loops even if not shown on the map. Rules for Contours 3. Contour lines bend upstream (uphill) when crossing a river. Rules for Contours 4. The maximum possible elevation for a hill is one less than the value that would have designated the next contour line. 90 80 In other words, the 70 highest possible 60 elevation of the hill is just 50 below the value of the next contour line, even though that line is not shown. Closely-Spaced Contours On a steep slope, the contour lines are close together. Widely-Spaced Contours On a gradual slope, the contour lines are far apart. A B Depressions Contour lines that show a depression, crater, or sinkhole on a map are represented by dashed lines (hachure marks) on the inside of a contour line.