Low-Grade Gliomas 26

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leptomeningeal Dissemination of Pilocytic Astrocytoma Via Hematoma in a Child

Neurosurg Focus 13 (1):Clinical Pearl 2, 2002, Click here to return to Table of Contents Leptomeningeal dissemination of pilocytic astrocytoma via hematoma in a child Case report MASARU KANDA, M.D., HIDENOBU TANAKA, M.D., PH.D., SOJI SHINODA, M.D., PH.D., AND TOSHIO MASUZAWA, M.D., PH.D. Department of Surgical Neurology, Jichi Medical School, Tochigi, Japan A case of recurrent pilocytic astrocytoma with leptomeningeal dissemination (LMD) is described. A cerebellar tumor was diagnosed in a 3-year-old boy, in whom resection was performed. When the boy was 6 years of age, recur- rence was treated with surgery and local radiotherapy. At age 13 years, scoliosis was present, but the patient was asymptomatic. Twelve years after initial surgery LMD was demonstrated in the lumbar spinal region without recur- rence of the original tumor. This tumor also was subtotally removed. During the procedure, a hematoma was observed adjacent to the tumor, but the border was clear. Histological examination of the spinal cord tumor showed features sim- ilar to those of the original tumor. There were no tumor cells in the hematoma. The MIB-1 labeling index indicated no malignant change compared with the previous samples. Radiotherapy was performed after the surgery. The importance of early diagnosis and management of scoliosis is emphasized, and the peculiar pattern of dissemination of the pilo- cytic astrocytoma and its treatment are reviewed. KEY WORDS • pilocytic astrocytoma • leptomeningeal dissemination • MIB-1 labeling index • radiation therapy • scoliosis -

Risk Factors for Gliomas and Meningiomas in Males in Los Angeles County1

[CANCER RESEARCH 49, 6137-6143. November 1, 1989] Risk Factors for Gliomas and Meningiomas in Males in Los Angeles County1 Susan Preston-Martin,2 Wendy Mack, and Brian E. Henderson Department of Preventive Medicine, University of Southern California School of Medicine, Los Angeles, California 90033 ABSTRACT views with proxy respondents, we were unable to include a large proportion of otherwise eligible cases because they were deceased or Detailed job histories and information about other suspected risk were too ill or impaired to participate in an interview. The Los Angeles factors were obtained during interviews with 272 men aged 25-69 with a County Cancer Surveillance Program identified the cases (26). All primary brain tumor first diagnosed during 1980-1984 and with 272 diagnoses had been microscopically confirmed. individually matched neighbor controls. Separate analyses were con A total of 478 patients were identified. The hospital and attending ducted for the 202 glioma pairs and the 70 meningioma pairs. Meningi- physician granted us permission to contact 396 (83%) patients. We oma, but not glioma, was related to having a serious head injury 20 or were unable to locate 22 patients, 38 chose not to participate, and 60 more years before diagnosis (odds ratio (OR) = 2.3; 95% confidence were aphasie or too ill to complete the interview. We interviewed 277 interval (CI) = 1.1-5.4), and a clear dose-response effect was observed patients (74% of the 374 patients contacted about the study or 58% of relating meningioma risk to number of serious head injuries (/' for trend the initial 478 patients). -

Central Nervous System

PRINCESS MARGARET CANCER CENTRE CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM LOW GRADE GLIOMAS CNS Site Group – Low Grade Gliomas Author: Dr. Norm Laperriere 1. INTRODUCTION 3 2. PREVENTION 3 3. SCREENING AND EARLY DETECTION 3 4. DIAGNOSIS AND PATHOLOGY 3 5. MANAGEMENT 4 5.1 MANAGEMENT ALGORITHMS 4 5.2 SURGERY 4 5.3 CHEMOTHERAPY 5 5.4 RADIATION THERAPY 5 6. ONCOLOGY NURSING PRACTICE 6 7. SUPPORTIVE CARE 6 7.1 PATIENT EDUCATION 6 7.2 PSYCHOSOCIAL CARE 6 7.3 SYMPTOM MANAGEMENT 6 7.4 CLINICAL NUTRITION 7 7.5 PALLIATIVE CARE 7 7.6 REHABILITATION 7 8. FOLLOW-UP CARE 7 Last Revision Date – April 2019 2 Low Grade Gliomas 1. Introduction • Grade I gliomas: pilocytic astrocytoma (PA), dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor (DNET), pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma, (PXA), ganglioglioma • Grade II gliomas: infiltrating astrocytoma, oligodendroglioma, mixed gliomas • annual incidence is approx. 1/100,000 This document is intended for use by members of the Central Nervous System site group of the Princess Margaret Hospital/University Health Network. The guidelines in this document are meant as a guide only, and are not meant to be prescriptive. There exists a multitude of individual factors, prognostic factors and peculiarities in any individual case, and for that reason the ultimate decision as to the management of any individual patient is at the discretion of the staff physician in charge of that particular patient’s care. 2. Prevention • genetic counseling for all NF1 carriers 3. Screening and Early Detection • baseline MRI brain for all newly -

Original Article Outcome of Supratentorial Intraaxial Extra Ventricular Primary Pediatric Brain Tumors

Original Article Outcome of supratentorial intraaxial extra ventricular primary pediatric brain tumors: A prospective study Mohana Rao Patibandla, Suchanda Bhattacharjee1, Megha S. Uppin2, Aniruddh Kumar Purohit1 Department of Neurosurgery, Krishna Institute of Medical Sciences Secunderabad, Departments of 1Neurosurgery and 2Pathology, Nizam’s Institute of Medical Sciences, Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh, India Address for correspondence: Dr. Mohana Rao Patibandla, Department of Neurosurgery, University of Colorado Denver, 13123, E 16th Ave, Aurora, CO 80045, USA. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Introduction: Tumors of the central nervous system (CNS) are the second most frequent malignancy of childhood and the most common solid tumor in this age group. CNS tumors represent approximately 17% of all malignancies in the pediatric age range, including adolescents. Glial neoplasms in children account for up to 60% of supratentorial intraaxial tumors. Their histological distribution and prognostic features differ from that of adults. Aims and Objectives: To study clinical and pathological characteristics, and to analyze the outcome using the Engel’s classification for seizures, Karnofsky’s score during the available follow‑up period of minimum 1 year following the surgical and adjuvant therapy of supratentorial intraaxial extraventricular primary pediatric (SIEPP) brain tumors in children equal or less than 18 years. Materials and Methods: The study design is a prospective study done in NIMS from October 2008 to January 2012. All the patients less than 18 years of age operated for SIEPP brain tumors proven histopathologically were included in the study. All the patients with recurrent or residual primary tumors or secondaries were excluded from the study. Post operative CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is done following surgery. -

Charts Chart 1: Benign and Borderline Intracranial and CNS Tumors Chart

Charts Chart 1: Benign and Borderline Intracranial and CNS Tumors Chart Glial Tumor Neuronal and Neuronal‐ Ependymomas glial Neoplasms Subependymoma Subependymal Giant (9383/1) Cell Astrocytoma(9384/1) Myyppxopapillar y Desmoplastic Infantile Ependymoma Astrocytoma (9412/1) (9394/1) Chart 1: Benign and Borderline Intracranial and CNS Tumors Chart Glial Tumor Neuronal and Neuronal‐ Ependymomas glial Neoplasms Subependymoma Subependymal Giant (9383/1) Cell Astrocytoma(9384/1) Myyppxopapillar y Desmoplastic Infantile Ependymoma Astrocytoma (9412/1) (9394/1) Use this chart to code histology. The tree is arranged Chart Instructions: Neuroepithelial in descending order. Each branch is a histology group, starting at the top (9503) with the least specific terms and descending into more specific terms. Ependymal Embryonal Pineal Choro id plexus Neuronal and mixed Neuroblastic Glial Oligodendroglial tumors tumors tumors tumors neuronal-glial tumors tumors tumors tumors Pineoblastoma Ependymoma, Choroid plexus Olfactory neuroblastoma Oligodendroglioma NOS (9391) (9362) carcinoma Ganglioglioma, anaplastic (9522) NOS (9450) Oligodendroglioma (9390) (9505 Olfactory neurocytoma Ganglioglioma, malignant (()9521) anaplastic (()9451) Anasplastic ependymoma (9505) Olfactory neuroepithlioma Oligodendroblastoma (9392) (9523) (9460) Papillary ependymoma (9393) Glioma, NOS (9380) Supratentorial primitive Atypical EdEpendymo bltblastoma MdllMedulloep ithliithelioma Medulloblastoma neuroectodermal tumor tetratoid/rhabdoid (9392) (9501) (9470) (PNET) (9473) tumor -

Central Nervous System Tumors General ~1% of Tumors in Adults, but ~25% of Malignancies in Children (Only 2Nd to Leukemia)

Last updated: 3/4/2021 Prepared by Kurt Schaberg Central Nervous System Tumors General ~1% of tumors in adults, but ~25% of malignancies in children (only 2nd to leukemia). Significant increase in incidence in primary brain tumors in elderly. Metastases to the brain far outnumber primary CNS tumors→ multiple cerebral tumors. One can develop a very good DDX by just location, age, and imaging. Differential Diagnosis by clinical information: Location Pediatric/Young Adult Older Adult Cerebral/ Ganglioglioma, DNET, PXA, Glioblastoma Multiforme (GBM) Supratentorial Ependymoma, AT/RT Infiltrating Astrocytoma (grades II-III), CNS Embryonal Neoplasms Oligodendroglioma, Metastases, Lymphoma, Infection Cerebellar/ PA, Medulloblastoma, Ependymoma, Metastases, Hemangioblastoma, Infratentorial/ Choroid plexus papilloma, AT/RT Choroid plexus papilloma, Subependymoma Fourth ventricle Brainstem PA, DMG Astrocytoma, Glioblastoma, DMG, Metastases Spinal cord Ependymoma, PA, DMG, MPE, Drop Ependymoma, Astrocytoma, DMG, MPE (filum), (intramedullary) metastases Paraganglioma (filum), Spinal cord Meningioma, Schwannoma, Schwannoma, Meningioma, (extramedullary) Metastases, Melanocytoma/melanoma Melanocytoma/melanoma, MPNST Spinal cord Bone tumor, Meningioma, Abscess, Herniated disk, Lymphoma, Abscess, (extradural) Vascular malformation, Metastases, Extra-axial/Dural/ Leukemia/lymphoma, Ewing Sarcoma, Meningioma, SFT, Metastases, Lymphoma, Leptomeningeal Rhabdomyosarcoma, Disseminated medulloblastoma, DLGNT, Sellar/infundibular Pituitary adenoma, Pituitary adenoma, -

Differentiation Between Pilocytic Astrocytoma and Glioblastoma: a Decision Tree Model Using Contrast-Enhanced Magnetic Resonance

European Radiology (2019) 29:3968–3975 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-018-5706-6 ONCOLOGY Differentiation between pilocytic astrocytoma and glioblastoma: a decision tree model using contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging-derived quantitative radiomic features Fei Dong1 & Qian Li1 & Duo Xu1 & Wenji Xiu2 & Qiang Zeng3 & Xiuliang Zhu1 & Fangfang Xu1 & Biao Jiang1 & Minming Zhang1 Received: 13 March 2018 /Revised: 8 July 2018 /Accepted: 6 August 2018 /Published online: 12 November 2018 # European Society of Radiology 2018 Abstract Objective To differentiate brain pilocytic astrocytoma (PA) from glioblastoma (GBM) using contrast-enhanced mag- netic resonance imaging (MRI) quantitative radiomic features by a decision tree model. Methods Sixty-six patients from two centres (PA, n = 31; GBM, n = 35) were randomly divided into training and validation data sets (about 2:1). Quantitative radiomic features of the tumours were extracted from contrast-enhanced MR images. A subset of features was selected by feature stability and Boruta algorithm. The selected features were used to build a decision tree model. Predictive accuracy, sensitivity and specificity were used to assess model performance. The classification outcome of the model was combined with tumour location, age and gender features, and multivariable logistic regression analysis and permutation test using the entire data set were performed to further evaluate the decision tree model. Results A total of 271 radiomic features were successfully extracted for each tumour. Twelve features were selected as input variables to build the decision tree model. Two features S(1, -1) Entropy and S(2, -2) SumAverg were finally included in the model. The model showed an accuracy, sensitivity and specificity of 0.87, 0.90 and 0.83 for the training data set and 0.86, 0.80 and 0.91 for the validation data set. -

Malignant CNS Solid Tumor Rules

Malignant CNS and Peripheral Nerves Equivalent Terms and Definitions C470-C479, C700, C701, C709, C710-C719, C720-C725, C728, C729, C751-C753 (Excludes lymphoma and leukemia M9590 – M9992 and Kaposi sarcoma M9140) Introduction Note 1: This section includes the following primary sites: Peripheral nerves C470-C479; cerebral meninges C700; spinal meninges C701; meninges NOS C709; brain C710-C719; spinal cord C720; cauda equina C721; olfactory nerve C722; optic nerve C723; acoustic nerve C724; cranial nerve NOS C725; overlapping lesion of brain and central nervous system C728; nervous system NOS C729; pituitary gland C751; craniopharyngeal duct C752; pineal gland C753. Note 2: Non-malignant intracranial and CNS tumors have a separate set of rules. Note 3: 2007 MPH Rules and 2018 Solid Tumor Rules are used based on date of diagnosis. • Tumors diagnosed 01/01/2007 through 12/31/2017: Use 2007 MPH Rules • Tumors diagnosed 01/01/2018 and later: Use 2018 Solid Tumor Rules • The original tumor diagnosed before 1/1/2018 and a subsequent tumor diagnosed 1/1/2018 or later in the same primary site: Use the 2018 Solid Tumor Rules. Note 4: There must be a histologic, cytologic, radiographic, or clinical diagnosis of a malignant neoplasm /3. Note 5: Tumors from a number of primary sites metastasize to the brain. Do not use these rules for tumors described as metastases; report metastatic tumors using the rules for that primary site. Note 6: Pilocytic astrocytoma/juvenile pilocytic astrocytoma is reportable in North America as a malignant neoplasm 9421/3. • See the Non-malignant CNS Rules when the primary site is optic nerve and the diagnosis is either optic glioma or pilocytic astrocytoma. -

Perinatal (Fetal and Neonatal) Astrocytoma: a Review

Childs Nerv Syst DOI 10.1007/s00381-016-3215-y REVIEW PAPER Perinatal (fetal and neonatal) astrocytoma: a review Hart Isaacs Jr.1,2 Received: 16 July 2016 /Accepted: 3 August 2016 # The Author(s) 2016. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract Keywords Fetal astrocytoma . Neonatal astrocytoma . Introduction The purpose of this review is to document the Perinatal astrocytoma . Intracranial hemorrhage . Congenital various types of astrocytoma that occur in the fetus and neo- brain tumor nate, their locations, initial findings, pathology, and outcome. Data are presented that show which patients are likely to sur- vive or benefit from treatment compared with those who are Introduction unlikely to respond. Materials and methods One hundred one fetal and neonatal Glial cells are the supportive elements of the central nervous tumors were collected from the literature for study. system (CNS) [22]. They include astrocytes, oligodendro- Results Macrocephaly and an intracranial mass were the most cytes, and ependymal cells, and the corresponding tumors common initial findings. Overall, hydrocephalus and intracra- originating from these cells astrocytoma, oligodendroglioma, nial hemorrhage were next. Glioblastoma (GBM) was the and ependymoma all of which are loosely called Bglioma^ most common neoplasm followed in order by subependymal [16, 22]. The term Bglioma^ is used interchangeably with giant cell astrocytoma (SEGA), low-grade astrocytoma, ana- astrocytoma to describe the more common subgroup of tu- plastic astrocytoma, and desmoplastic infantile astrocytoma mors [22]. (DIA). Tumors were detected most often toward the end of Glioma (astrocytoma) is the leading CNS tumor in chil- the third trimester of pregnancy. -

Neuropathology Neoadjuvant Chemoradiation and Pancreatectomy

378A ANNUAL MEETING ABSTRACTS 1602 Pathologic Complete Response Is Associated with Good Prognosis in Patient with Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Who Received Neuropathology Neoadjuvant Chemoradiation and Pancreatectomy. Q Zhao, A Rashid, Y Gong, M Katz, J Lee, R Wolf, C Charnsangavej, G Varadhachary, P 1604 Nestin, an Important Marker for Differentiating Oligodendroglioma Pisters, E Abdalla, J-N Vauthey, H Wang, H Gomez, J Fleming, J Abbruzzese, H Wang. from Astrocytic Tumors. MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX. SH Abu-Farsakh, IA Sbeih, HA Abu-Farsakh. Jordan University, Amman, Jordan; Ibn Background: Patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA) has poor Hytham Hospital, Amman, Jordan; First Medical Lab, Amman, Jordan. prognosis. To improve the clinical outcome, most patients with PDA are treated with Background: Nestin is an acronym for neuroepithelial stem cell protein. It is an neoadjuvant chemoradiation prior to surgery at our institution. In this group of patients, intermediate filament protein expressed in proliferating cells during the developmental pathologic complete response (PCR) is rarely observed in subsequent pancreatectomies. stages in a variety of embryonic and fetal tissues. It is also expressed in some adult stem/ However, the prognostic significance of PCR is not clear. progenitor cell populations, such as newborn vascular endothelial cell. Differentiation Design: Among 442 patients with PDA who received neoadjuvant chemoradiation and between astrocytic tumors and oligodenoglioma tumor is of paramount importance pancreatectomy from 1995 to 2010, 11 (2%) patients with PCR were identified. The because of different lines of treatment and different prognosis. cytologic diagnosis on pre-therapy tumor was reviewed and PCR in pancreatectomies Design: We performed Nestin immunostaining on paraffin blocks of 16 cases of was confirmed in all patients. -

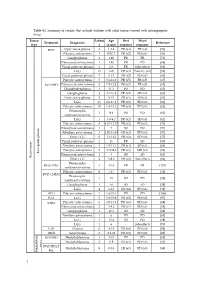

Table S1. Summary of Studies That Include Children with Solid Tumors Treated with Antiangiogenic Drugs

Table S1. Summary of studies that include children with solid tumors treated with antiangiogenic drugs. Tumor Patient Age Best Worst Treatment Diagnostic Reference type s (years) response response BVZ Optic nerve glioma 4 1.2-4 PR (x4) PR (x4) [56] Pilocytic astrocytoma 3 0.92-7 PR (x2) PD (x1) [56] Ganglioglioma 1 1.92 PR PR [56] Pilomyxoid astrocytoma 1 1.92 PR PD [68] Visual pathway glioma 1 2.6 PR Side effects [66] LGG 15 1-20 CR (x3) Toxicity (x1) [58] Visual pathway glioma 3 6-13 PR (x2) PD (x1) [60] Pilocytic astrocytoma 5 3.1-11.2 PR (x5) PR (x5) [65] BVZ+IRO Pilomyxoid astrocytoma 2 7.9-12.2 PR (x2) PR (x2) [65] Oligodendroglioma 1 11.1 PD PD [65] Ganglioglioma 3 4.1-16.8 PR (x2) SD (x1) [65] Optic nerve glioma 2 9-15 PR (x1) SD (x1) [63] LGG 35 0.6-17.6 PR (x2) PD (x8) [61] Pilocytic astrocytoma 10 1.8-15.3 PR (x4) PD (x1) [62] Pleomorphic 1 9.4 PD PD [62] xanthoastrocytoma LGG 5 3.9-9.2 PR (x2) SD (x3) [62] Pilocytic astrocytoma 4 4.67-12.17 PR (x2) PD (x3) [57] Pilomyxoid astrocytoma 1 3 SD PD [57] Fibrillary astrocytoma 3 1.92-11.08 CR (x1) PD (x3) [57] Other LGG 6 1-13.42 PR (x2) PD (x6) [57] Visual pathway glioma 1 11 PR SD [60] Fibrillary astrocytoma 3 1.5-11.1 CR (x1) SD (x1) [64] Pilocytic astrocytoma 2 3.75-9.8 PR (x1) MR (x1) [64] Low-grade glioma Pilomyxoid astrocytoma 1 3 SD SD [64] Brain tumor Brain tumor Other LGG 4 3-9.6 PR (x2) Side effects [64] Pleomorphic BVZ+TMZ 1 13.4 PR PR [153] xanthoastrocytoma Pilocytic astrocytoma 9 5-17 PR (x3) PD (x3) [59] BVZ+CHEM Pleomorphic 1 18 SD PD [59] xanthoastrocytoma Ganglioglioma -

Losses of Chromosomal Arms 1P and 19Q in the Diagnosis of Oligodendroglioma

Losses of Chromosomal Arms 1p and 19q in the Diagnosis of Oligodendroglioma. A Study of Paraffin- Embedded Sections Peter C. Burger, M.D., A. Yuriko Minn, M.S., Justin S. Smith, M.D., Ph.D., Thomas J. Borell, B.S., Anne E. Jedlicka, M.S., Brenda K. Huntley, B.S., Patricia T. Goldthwaite, M.S., Robert B. Jenkins, M.D., Ph. D., Burt G. Feuerstein, M.D., Ph.D. The Departments of Pathology (PCB, PTG) and Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine (AEJ), Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland; Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Mayo Clinic (JSS, TJB, BKH, RBJ), Rochester, Minnesota; and Departments of Laboratory Medicine and Neurosurgery and Brain Tumor Research Center, University of California at San Francisco School of Medicine (BGF, AYM), San Francisco, California It is the impression of some pathologists that many Comparative genomic hybridization (CGH), fluores- gliomas presently designated as oligodendrogliomas cence in situ hybridization (FISH), polymerase chain would have been classified in the past as astrocyto- reaction–based microsatellite analysis, and p53 se- mas with little thought about the possibility of an quencing were performed in paraffin-embedded ma- oligodendroglial component. It also appears that the terial from 18 oligodendrogliomas and histologically relative incidence of the diagnoses of oligodendrogli- similar astrocytomas. The study was undertaken be- oma and astrocytomas varies widely from institution cause of evidence that concurrent loss of both the 1p to institution, suggesting that diagnostic criteria dif- and 19q chromosome arms is a specific marker for fer. In some laboratories, even minor or focal nuclear oligodendrogliomas. Of the six lesions with a review roundness or perinuclear haloes are considered to be diagnosis of oligodendroglioma, all had the predicted evidence of oligodendroglial differentiation, whereas loss of 1p and 19q seen by CGH, FISH, and polymerase pathologists elsewhere require the more classical fea- chain reaction.