Terminating Cereal Rye After Seeding Soybeans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celiac Disease Resource Guide for a Gluten-Free Diet a Family Resource from the Celiac Disease Program

Celiac Disease Resource Guide for a Gluten-Free Diet A family resource from the Celiac Disease Program celiacdisease.stanfordchildrens.org What Is a Gluten-Free How Do I Diet? Get Started? A gluten-free diet is a diet that completely Your first instinct may be to stop at the excludes the protein gluten. Gluten is grocery store on your way home from made up of gliadin and glutelin which is the doctor’s office and search for all the found in grains including wheat, barley, gluten-free products you can find. While and rye. Gluten is found in any food or this initial fear may feel a bit overwhelming product made from these grains. These but the good news is you most likely gluten-containing grains are also frequently already have some gluten-free foods in used as fillers and flavoring agents and your pantry. are added to many processed foods, so it is critical to read the ingredient list on all food labels. Manufacturers often Use this guide to select appropriate meals change the ingredients in processed and snacks. Prepare your own gluten-free foods, so be sure to check the ingredient foods and stock your pantry. Many of your list every time you purchase a product. favorite brands may already be gluten-free. The FDA announced on August 2, 2013, that if a product bears the label “gluten-free,” the food must contain less than 20 ppm gluten, as well as meet other criteria. *The rule also applies to products labeled “no gluten,” “free of gluten,” and “without gluten.” The labeling of food products as “gluten- free” is a voluntary action for manufacturers. -

Plant-Based Milk Alternatives

Behind the hype: Plant-based milk alternatives Why is this an issue? Health concerns, sustainability and changing diets are some of the reasons people are choosing plant-based alternatives to cow’s milk. This rise in popularity has led to an increased range of milk alternatives becoming available. Generally, these alternatives contain less nutrients than cow’s milk. In particular, cow’s milk is an important source of calcium, which is essential for growth and development of strong bones and teeth. The nutritional content of plant-based milks is an important consideration when replacing cow’s milk in the diet, especially for young children under two-years-old, who have high nutrition needs. What are plant-based Table 1: Some Nutrients in milk alternatives? cow’s milk and plant-based Plant-based milk alternatives include legume milk alternatives (soy milk), nut (almond, cashew, coconut, macadamia) and cereal-based (rice, oat). Other ingredients can include vegetable oils, sugar, and thickening ingredients Milk type Energy Protein Calcium kJ/100ml g/100ml mg/100ml such as gums, emulsifiers and flavouring. Homogenised cow’s milk 263 3.3 120 How are plant-based milk Legume alternatives nutritionally Soy milk 235-270 3.0-3.5 120-160* different to cow’s milk? Nut Almond milk 65-160 0.4-0.7 75-120* Plant-based milk alternatives contain less protein and Cashew milk 70 0.4 120* energy. Unfortified versions also contain very little calcium, B vitamins (including B12) and vitamin D Coconut milk** 95-100 0.2 75-120* compared to cow’s milk. -

Wic Approved Food Guide

MASSACHUSETTS WIC APPROVED FOOD GUIDE GOOD FOOD and A WHOLE LOT MORE! June 2021 Shopping with your WIC Card • Buy what you need. You do not have to buy all your foods at one time! • Have your card ready at check out. • Before scanning any of your foods, tell the cashier you are using a WIC Card. • When the cashier tells you, slide your WIC Card in the Point of Sale (POS) machine or hand your WIC Card to the cashier. • Enter your PIN and press the enter button on the keypad. • The cashier will scan your foods. • The amount of approved food items and dollar amount of fruits and vegetables you purchase will be deducted from your WIC account. • The cashier will give you a receipt which shows your remaining benefit balance and the date benefits expire. Save this receipt for future reference. • It’s important to swipe your WIC Card before any other forms of payment. Any remaining balance can be paid with either cash, EBT, SNAP, or other form of payment accepted by the store. Table of Contents Fruits and Vegetables 1-2 Whole Grains 3-7 Whole Wheat Pasta Bread Tortillas Brown Rice Oatmeal Dairy 8-12 Milk Cheese Tofu Yogurt Eggs Soymilk Peanut Butter and Beans 13-14 Peanut Butter Dried Beans, Lentils, and Peas Canned Beans Cereal 15-20 Hot Cereal Cold Cereal Juice 21-24 Bottled Juice - Shelf Stable Frozen Juice Infant Foods 25-27 Infant Fruits and Vegetables Infant Cereal Infant Formula For Fully Breastfeeding Moms and Babies Only (Infant Meats, Canned Fish) 1 Fruits and Vegetables Fruits and Vegetables Fresh WIC-Approved • Any size • Organic allowed • Whole, cut, bagged or packaged Do not buy • Added sugars, fats and oils • Salad kits or party trays • Salad bar items with added food items (dip, dressing, nuts, etc.) • Dried fruits or vegetables • Fruit baskets • Herbs or spices Any size Any brand • Any fruit or vegetable Shopping tip The availability of fresh produce varies by season. -

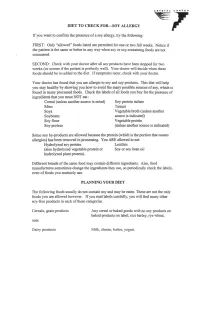

Diet to Check For—Soy Allergy

CRYSTAL CANYON DIET TO CHECK FOR—SOY ALLERGY If you want to confirm the presence of a soy allergy, try the following: FIRST: Only "allowed" foods listed are permitted for one or two full weeks. Notice if the patient is the same or better in any way when soy or soy-containing foods are not consumed. SECOND: Check with your doctor after all soy products have been stopped for two weeks (or sooner if the patient is perfectly well). Your doctor will decide when these foods should be re-added to the diet. If symptoms recur, check with your doctor. Your doctor has found that you are allergic to soy and soy products. This diet will help you stay healthy by showing you how to avoid the many possible sources of soy, which is found in many processed foods. Check the labels of all foods you buy for the presence of ingredients that you must NOT eat.: Cereal (unless another source is noted) Soy protein isolate Miso Tamari Soya Vegetable broth (unless another Soybeans source is indicated) Soy flour Vegetable protein Soy protein (unless another source is indicated) Some soy by-products are allowed because the protein (which is the portion that causes allergies) has been removed in processing. You ARE allowed to eat: Hydrolyzed soy protein Lecithin (also hydrolyzed vegetable protein or Soy or soy bean oil hydrolyzed plant protein). Different brands of the same food may contain different ingredients. Also, food manufactures sometimes change the ingredients they use, so periodically check the labels, even of foods you routinely use. -

Cereal Structure and Its Relationship to Nutritional Quality

Food Structure Volume 8 Number 1 Article 13 1989 Cereal Structure and Its Relationship to Nutritional Quality S. H. Yiu Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/foodmicrostructure Part of the Food Science Commons Recommended Citation Yiu, S. H. (1989) "Cereal Structure and Its Relationship to Nutritional Quality," Food Structure: Vol. 8 : No. 1 , Article 13. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/foodmicrostructure/vol8/iss1/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western Dairy Center at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Food Structure by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FOOD MICROSTRUCTURE, Vol. 8 (1989), pp. 99- 113 0730- 5419/89$3 . 00+. 00 scanning Microscopy International, Chicago (AMF O'Hare) , IL 60666 USA CEREAL STRUCTURE AND ITS RELATIONSHIP TO NUTRITIONAL QUALITY S. H. Yiu Food Research Centre, Agriculture Canada, Ottawa, OntarIo, Canada KlA OC6 Abstract Introduction Factors that determine the digest1b11Hy of Cerea 1 s are good sources of carbohydrates carbohydrates and mi nera 1s 1n cerea 1 s are exa and minerals important for sustaining the energy mined . Most carbohydrates and minerals in ce and growth requirements of humans and animals. reals are structurally bound, either surrounded Cereals also contain dietary fiber. Increased by or associated with cell wall components not consumption of dietary fiber has been associated easily digested by non-ruminant animals and hu with various health benefits (Trowell , 1976; mans. Treatments such as mechanical grinding and Anderson and Chen, 197g). heat improve the digestibility of nutrients . -

Food Fact Sheet: Calcium

Food Fact Sheet: Calcium Calcium is important at all ages for strong bones and teeth. This Food Fact Sheet lists how much calcium different people need, what foods and drinks are good sources, and how you can add it to your diet. Why do I need calcium? Calcium is a mineral that is needed to maintain strong bones. It is also needed for healthy muscle and nerve function. How much calcium do I need? Table 1 - Daily guideline amounts Group Age (years) Calcium (mg) per day Infants Under 1 525 Children 1-3 350 4-6 450 7-10 550 Adolescents 11-18 800 (girls) 1000 (boys) Adults 19+ 700 Those who are breastfeeding 1250 Women past the menopause 1200 Men over 55 years 55+ 1200 Coeliac Disease 19+ 1000-1500 Osteoporosis 19+ 1000 Inflammatory Bowel disease 19+ 1000 You are more at risk of calcium deficiency if you: are on a cow’s milk or lactose-free diet have coeliac disease have osteoporosis are breastfeeding are past the menopause Where do I get calcium from? Calcium in dairy products Quantity Calcium (mg) Cow’s milk, including Lactose free 100ml 120 Sheep’s milk 100ml 170 Goat’s milk 100ml 100-120 Cheese: matchbox-size: Cheddar 30g 222 Edam/Halloumi 30g 238 Cottage 30g 38 Cheese triangle 1 triangle (15-17.5g) 84-138 Yoghurt (plain) 120g 181 (low fat) 193 (whole) Fromage frais 1 pot (47-85g) 80-128 Rice pudding or custard pots 1 pot (55g) 60 Malted milk drink 25g serving in 200ml semi-skimmed milk 444-800 Rice pudding ½ large tin (200g) 198 Custard - tinned 1 serving (120ml) 110-127 Milk chocolate 30g 68 Non dairy sources of calcium Calcium-fortified products Calcium-fortified plant-based alternatives to milk 100 ml 120-189 e.g. -

Cereal Rye Cover Crop Effect on Soybean Yield

Cereal Rye Cover Crop Effect on Soybean Yield Alan Sundermeier, Agriculture & Natural Resources Extension Educator Jim Hoorman, Agriculture & Natural Resources Extension Educator Objective To evaluate effect of cereal rye cover crop on soybean yield. Background Cooperator: O.A.R.D.C NW Branch Variety: Pioneer 93Y10 County: Wood Planting Date: May 31, 2010 Nearest Town: Hoytville Planting Rate: 180,000 Drainage: Systematic tiled Row Width: 7.5 in. Soil type: Hoytville, clay Herbicides: Glyphomax xtra, 2,4-D, Canopy Tillage: notill Harvest Date: October 1, 2010 Previous Crop: Corn Methods The entries were replicated four times in a randomized complete block design. Plot size- 10 x 80 feet each entry. Harvest data was collected from the center 5 feet. On November 6, 2009, cereal rye cover crop was drilled into corn residue at a rate of 1.5 bu/acre. On April 14, 2010 these cover crop plots were killed with Glyphosate, 2,4-D ester spray. Plots were planted with a drill no-till. Results Soybean Yield (bu/A) Response to Cereal Rye Cover Crop Yield (bu/A) Cereal Rye 51.0 a No cover crop 46.1 b LSD (0.20) 4.5 Summary Using a cereal rye cover crop had a significant soybean yield increase when compared to no cover crop. July and August were drier than normal and the rye residue may have behaved as a mulch preserving moisture during these dry months. Planting was delayed, so soil temperatures were warm by the time of planting so the rye residue did not interfere with warming of the soil. -

Vegetarian & Vegan Diets

VEGETARIAN & VEGAN DIETS OVERVIEW ON COURSE TYPICAL OPTIONS The typical meal at a Costa While traveling with Outward Bound BREAKFAST Rican“soda” (restaurant) is called a Costa Rica, we make every effort to casado. It usually consists of gallo • Buttermilk Pancakes accommodate special diets. There • Cereal with Milk or Soy Milk pinto (rice and beans), fried plantains, is usually at least one vegetarian/ salad, cheese and some meat. Locals (vegan) vegan on every course, and we strive • Granola (vegan) have a different understandings to purchase locally and seasonally. of the term “vegetarian,” so it is • Tropical Fruit (vegan) Furthermore, as stewards of the • Gallo Pinto (vegan) best to specify exactly what you environment we have a very strict cannot eat (ex. ni carne, ni pollo, ni • Breakfast Burritos no-beef policy due to the correlation • Scrambled Eggs pescado, ni huevos, ni productos between deforestation and cattle. lácteos como mantequilla y leche). • French Toast • Oatmeal (vegan) Vegetarians and vegans will always Locally grown bananas, mangos, have options at every meal. While LUNCH papayas and pineapples are on course, many meals will be • Peanut Butter and Jelly abundant. You should also try some vegetarian due to unfeasibility of of the more interesting tropical fruits, Sandwiches procuring/refrigerating meat and • Gallo Pinto (vegan) such as zapotes, mamones chinos, concerns about contamination. tamarindo, guayabas and maracuyas, • Salad (vegan) Texturized soy protein is common, • Hard Boiled Eggs among others. On base, we make but tempeh, seitan and tofu are many fresh juices out of these! not readily available. The bulk of DINNER your protein intake will stem from • Chili with Texturized Soy Protein Unfortunately, while the climate of legumes – as almost all meals consist (vegan) Costa Rica is ideal for tropical fruits, the of some version of gallo pinto and • Spaghetti (vegan) variety and quality of vegetables are our trail mix contains peanuts. -

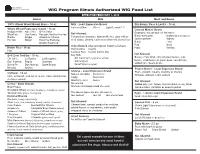

WIC Program Illinois Authorized WIC Food List

State of Illinois Department of Human Services WIC Program Illinois Authorized WIC Food List EFFECTIVE FEBRUARY 1, 2019 Grains Milk Meat and Beans 100% Whole Wheat Bread, Buns - 16 oz Milk - Least Expensive Brand Dry Beans, Peas & Lentils - 16 oz Fat Free/Skim Whole Light/Lowfat/1% Whole Wheat Pasta (any shape) - 16 oz Canned Mature Beans Hodgson Mill Racconto Great Value Examples include but not limited to: ShurFine Our Family Ronzoni Healthy Harvest Not Allowed: Black-eyed peas Garbanzo (chickpeas) Barilla Kroger America’s Choice Flavored or chocolate, buttermilk, rice, goat milk or Hy-Vee Meijer Essential Everyday shelf stable, almond, cashew or other milk alternatives Great northern Kidney Simply Balanced Black Lima Only Allowed when printed on Food Instrument: Red Navy Brown Rice - 16 oz Half Gallons Quarts Pinto Refried Plain Lactose Free Instant Nonfat Dry Not Allowed: Soft Corn Tortillas - 16 oz Soy Milk Soups of any kind, canned green beans, wax Chi Chi’s La Burrita La Banderita 8th Continent (original or vanilla) beans, snap beans or green peas, seasonings, Don Pancho Pepito Guerrero Silk (original) added fats, meats or oils Santa Fe Don Marcos Store Brand Great Value (original) Mission Azteca Peanut Butter - Least Expensive Brand Cheese - Least Expensive Brand Oatmeal - 16 oz Plain, smooth, creamy, crunchy or chunky Natural Cheddar Provolone All types allowed in low sodium Old Fashioned, Traditional, Quick-Cook, Rolled Oats Colby Muenster (no flavors added) Monterey Jack Swiss Not Allowed: Cereal - Store Brands Mozzarella Added -

How to Feed Your Baby Step-By-Step Age Food Group Foods Daily

How to Feed Your Baby Step-by-Step Every baby is special. Don’t worry if your baby eats a little more or a little less than this guide suggests. In fact, this is perfectly normal. The suggested serving sizes are only guidelines to help you get started. Please contact your provider if you have any questions. Age Food Foods Daily Suggested Feeding Tips Group Servings Serving Size 0-4 Milk Breast milk OR 8-12/on Nurse baby at least 5-10 minutes on each breast. Formula 0-1 Months demand 2-5 oz Your baby should not go more than 3-4 hours Months 1-2 Months 6-8 3-6 oz without feeding in the first few weeks of life 2-3 Months 5-7 4-7 oz Six wet diapers a day is a good sign. 3-4 Months 4-7 6-8 oz There’s no need to force baby to finish a bottle. *Usually milk based, iron fortified. Putting baby to bed with a bottle could cause choking and tooth decay. Heating in the microwave is NOT recommended. Breastfed babies need 10 minutes of sun exposure 2x/week to get vitamin D. They should also take a vitamin daily 4-6 Milk Breast milk OR 4-6 Start with 1 meal of solids each day. Formula 4-6 6-8 oz Start baby on rice baby cereal (iron-fortified). Months Feed only one new cereal each week. Grain Baby cereal (iron-fortified) 2 1-2 Tbsp There’s no need to add salt or sugar to cereal. -

Cereal Grains Structure & Composition Topics of Discussion

Ist US-Brazil Fulbright Course on Biofuels, Sao Singh – Corn Structure and Composition Paulo, Brazil Cereal Grains Structure & Composition Vijay Singh Associate Professor Department of Agricultural & Biological Engineering University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL 1st Brazil-U.S. Biofuels Short Course São Paulo, Brazil July 27 - August 7, 2009 Topics of Discussion • Structure of Corn Kernel – Hand dissection exercise •Starch • Protein •Oil •Fiber • Other Constituents • Corn Composition University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Ist US-Brazil Fulbright Course on Biofuels, Sao Singh – Corn Structure and Composition Paulo, Brazil Structure of Cereal Grains • Cereals are members of grass family • Produce dry , one-seeded fruit , called caryopsis • Caryopsis is also called kernel or grain • Caryopsis consists of – Fruit coat or pericarp, which surrounds seed and is tightly adhered to seed coat – Seed, which consists of germ or embryo and endosperm enclosed bllididdby a nucellar epidermis and a seed coat • All cereal grains have these same parts in approx. same relationship to each other Structure of Corn Kernel Pericarp Endosperm Germ Tip Cap University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Ist US-Brazil Fulbright Course on Biofuels, Sao Singh – Corn Structure and Composition Paulo, Brazil Scanning Electron Micrograph (SEM) of Dissected Steeped Corn Kernel Pericarp Endosperm Pericarp • 5 to 6% of kernel dry weight Cuticle Epidermis Mesocarp Cross cells Tube cells Seed coat • Cells in pericarp: hollow tubes, channels for water absorption via tip cap • Seed coat: semipermeable • Walls of pericarp contain cellulose and pentosans, no lignin. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Ist US-Brazil Fulbright Course on Biofuels, Sao Singh – Corn Structure and Composition Paulo, Brazil Aleurone layer • Aleurone layer beneath seed coat • Aleurone layer cells contain protein bodies (good amino acid profile), oil bodies, and no starch. -

Dietary Avoidance – Wheat Allergy

Dietary avoidance – wheat allergy Wheat is found in many foods and often in foods we do not suspect. Avoiding wheat is essential for individuals with confirmed wheat allergy. Therefore, it is important to read and understand food labels to be able to choose appropriate foods. The following foods and ingredients CONTAIN wheat and should be avoided: Atta flour Graham flour Wheat Bulgar Kamut Wheat bran Burghul Matzoh Wheat flour Cous cous Seitan Wheat germ Cracker meal Semolina Wheat meal Durum Spelt Wheat starch Farina Tabouleh Wheat berries Gluten Triticale Check labels on the following foods to see if they contain wheat and if they do, avoid them: Baked goods Flavouring (natural/artificial) Pasta/noodles Battered foods Hydrolysed vegetable protein Pastry/tarts Beer (HVP) Playdough Biscuits – sweet and savoury Ice cream cones Processed meats Bread (other than gluten free) Icing sugar Rusks Breadcrumbs Instant drink mixes Sauces/gravy mixes Breakfast cereal Liquorice Soy sauce Cakes/muffins Lollies Soups Canned soups/stocks Malt, malted milk Snack foods Cereal extract Mustard Starch Coffee substitutes Meat/seafood substitutes Stock cubes Cornflour (from wheat) Multigrain or wholemeal foods Surimi Donuts Pancakes/waffles Vegetable gum/starch The following ingredients are made from wheat but are tolerated by individuals with wheat allergy: Caramel colour. Glucose powder (from wheat). Dextrose (from wheat). Glucose syrup (from wheat). Gluten free foods Gluten is one of many proteins in wheat, barley, oats and rye. Most individuals with wheat allergy can tolerate oats, but the decision to include should be discussed with your allergy specialist. Approximately 20% of individuals with wheat allergy may be allergic to other cereals (such as barley, rye or oats).