3.0 Affected Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dixon Entrance

118 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 8, Chapter 4 19 SEP 2021 Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 8—Chapter 4 131°W 130°W NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml 133°W 132°W UNITEDCANADA ST ATES 17420 17424 56°N A 17422 C L L U A S R N R 17425 E I E N N E V C P I E L L A S D T N G R A I L B A G E E I L E T V A H N E D M A L 17423 C O C M I H C L E S P A B A L R N N I A A N L A N C C D E 17428 O F W 17430 D A 17427 Ketchikan N L A E GRAVINA ISLAND L S A T N I R S N E E O L G T R P A E T A S V S I E L N A L P I A S G S L D I L A G O N E D H D C O I N C 55°N H D A A N L N T E E L L DUKE ISLAND L N I I S L CORDOVA BAY D N A A N L T D R O P C Cape Chacon H A T H A 17437 17433 M S O Cape Muzon U N 17434 D DIXON ENTRANCE Langara Island 17420 54°N GRAHAM ISLAND HECATE STRAIT (Canada) 19 SEP 2021 U.S. -

Geologic Map of the Ketchikan and Prince Rupert Quadrangles, Southeastern Alaska

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR TO ACCOMPANY MAP I-1807 U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE KETCHIKAN AND PRINCE RUPERT QUADRANGLES, SOUTHEASTERN ALASKA By Henry C. Berg, Raymond L. Elliott, and Richard D. Koch INTRODUCTION This pamphlet and accompanying map sheet describe the geology of the Ketchikan and Prince Rupert quadrangles in southeastern Alaska (fig. 1). The report is chiefly the result of a reconnaissance investigation of the geology and mineral re sources of the quadrangles by the U.S. Geological Survey dur ing 1975-1977 (Berg, 1982; Berg and others, 1978 a, b), but it also incorporates the results of earlier work and of more re cent reconnaissance and topical geologic studies in the area (fig. 2). We gratefully acknowledge the dedicated pioneering photointerpretive studies by the late William H. (Hank) Con don, who compiled the first 1:250,000-scale reconnaissance geologic map (unpublished) of the Ketchikan quadrangle in the 1950's and who introduced the senior author to the study 130' area in 1956. 57'L__r-'-'~~~;:::::::,~~.::::r----, Classification and nomenclature in this report mainly fol low those of Turner (1981) for metamorphic rocks, Turner and Verhoogen (1960) for plutonic rocks, and Williams and others (1982) for sedimentary rocks and extrusive igneous rocks. Throughout this report we assign metamorphic ages to various rock units and emplacement ages to plutons largely on the basis of potassium-argon (K-Ar) and lead-uranium (Pb-U) (zircon) isotopic studies of rocks in the Ketchikan and Prince Rupert quadrangles (table 1) and in adjacent areas. Most of the isotopic studies were conducted in conjunction with recon naissance geologic and mineral resource investigations and re 0 100 200 KILOMETER sulted in the valuable preliminary data that we cite throughout our report. -

Gravina Access Tongass Narrows Biop AKR-2018-9806

Endangered Species Act (ESA) Section 7(a)(2) Biological Opinion for Construction of the Tongass Narrows Project (Gravina Access) Public Consultation Tracking System (PCTS) Number: AKR-2018-9806 Action Agencies: Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities (ADOT&PF) on behalf of the Federal Highway Administration (FHA) Affected Species and Determinations: Is Action Likely Is Action Likely Is Action to Adversely To Destroy or Likely To ESA-Listed Species Status Affect Species or Adversely Jeopardize Critical Modify Critical the Species? Habitat? Habitat? Humpback whale (Megaptera Threatened Yes No N/A novaeangliae) Mexico DPS Consultation Conducted By: National Marine Fisheries Service Issued By: ____________________________________ James W. Balsiger, Ph.D. Administrator, Alaska Region Date: February 6, 2019 Ketchikan Tongass Narrows Project PCTS AKR-2018-9806 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables .................................................................................................................................. 4 List of Figures ................................................................................................................................. 4 Terms and Abbreviations ................................................................................................................ 6 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 8 1.1 Background ..................................................................................................................... -

Tongass Narrows Waterway Guide

TONGASS NARROWS VOLUNTARY WATERWAY GUIDE Revisions Est. February 28, 1999 October 1, 2006 April 30, 2007 April 10, 2010 April 24, 2012 *** The Tongass Narrows Voluntary Waterway Guide (TNVWG) is intended for use by all vessel operators when transiting Tongass Narrows from the intersection of Nichols Passage and Revillagigedo Channel on the Southeastern-most end to Guard Island on the Northwest end of the narrows. The members of the Tongass Narrows Work Group (TNWG), which included representatives from the following waterway user groups, developed this Guide in an effort to enhance the safety of navigation on this congested waterway: United States Coast Guard · Federal Aviation Administration Southeast Alaska Pilots Association · Cruise Line Agencies of Alaska Commercial and private floatplane operators · Small passenger vessels Commercial Kayak Operators · Commercial freight transporters Pennock-Gravina Island Association · Charter vessel operators Recreational boat operators · Local City-Borough · Waterfront Facility Operators Commercial fishing interests · Alaska Marine Highway System This Guide is published and distributed by the United States Coast Guard. For more information contact the: U.S. Coast Guard Marine Safety Detachment 1621 Tongass Ave. Ketchikan, AK 99901 (907) 225-4496 *** Disclaimer The Tongass Narrows Work Group’s TNVWG provides suggestions and recommended guidelines that are intended to assist persons operating vessels on the Tongass Narrows, regardless of type of vessel. This Guide is meant to complement and not replace the federal and state laws and regulations that govern maritime traffic on the Narrows. Prudent mariners should not rely on the Guide as their only source of information about vessel traffic patterns and safe navigation practices in Tongass Narrows, and should comply with all applicable laws and regulations. -

EJC Cover Page

Early Journal Content on JSTOR, Free to Anyone in the World This article is one of nearly 500,000 scholarly works digitized and made freely available to everyone in the world by JSTOR. Known as the Early Journal Content, this set of works include research articles, news, letters, and other writings published in more than 200 of the oldest leading academic journals. The works date from the mid-seventeenth to the early twentieth centuries. We encourage people to read and share the Early Journal Content openly and to tell others that this resource exists. People may post this content online or redistribute in any way for non-commercial purposes. Read more about Early Journal Content at http://about.jstor.org/participate-jstor/individuals/early- journal-content. JSTOR is a digital library of academic journals, books, and primary source objects. JSTOR helps people discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content through a powerful research and teaching platform, and preserves this content for future generations. JSTOR is part of ITHAKA, a not-for-profit organization that also includes Ithaka S+R and Portico. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. ... .. .. CAPTAIN ROBIERT GRAY design adopted by Congress on........... June I... 7. Taken fro ...hoorph o large ol paining by n eastrn -.I4 DallyJour7al, ad use for he fistartst...........kson,.ublishe.of.th.Orego tme ina Souenir ditio of tat paer i I905. The photograph was presented to the..........Portland. Press......... .....b. "Columbia"was built.'near:Boston in 5....and was.broken.topieces in 8o. It wasbelieved the thisfirst was9vessel the_original to carry flag the made.by.Mrs..Betsy.Ross.accordingIto.theStars and Stripes arou Chno on,opst soi. -

Information to Users

Spanish Exploration In The North Pacific And Its Effect On Alaska Place Names Item Type Thesis Authors Luna, Albert Gregory Download date 05/10/2021 11:44:10 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/8541 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6* x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet

NFS Form 10-900 I M t: U 11V fc I, . J ?? V &HJB : Jo. 10024-0018 > (j (Oct. 1990) j r> ' - - . ..,-,-... -'Ml,' (j? ^ United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NAT. REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLAGES National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NFS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property ____________ __ historic name ___Mary Island Light Station______. other names/site number Mary Island Lighthouse (AHRS Site No. KET-024) 2. Location street & number East shore, north end of Mary Island, between the Revillagigedo Channel and Felice Strait about 6-3/8 miles south of Revillagigedo Island. |"~ not for publication city or town: Ketchikan____________I* vicinity state Alaska code: AK county Prince of Wales-Outer Ketchikan Census Area code 201 zipcode 99901. 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this p" nomination [~~ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of istoric Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Reconnaissance Engineering Geology of the Metlakatla Area, Annette Island, Alaska, with Emphasis on Evaluation of Earthquakes and Other Geologic Hazards

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Reconnaissance Engineering Geology of the Metlakatla Area, Annette Island, Alaska, With Emphasis on Evaluation of Earthquakes and Other Geologic Hazards By Lynn. A. Yehle Open-file Report 77-272 1977 This report is preliminary and has not been edited or reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey standards or nomenclature. Contents Page Abstract 1 Introduction ~ 5 Geography- 7 Glaciation and associated land- and sea-level changes 10 Descriptive geology 13 Regional setting 13 Local geologic setting - 15 Description of geologic map units ________ 15 Metamorphic rocks (Pzmr) - 18 Diamicton deposits (Qd) 19 Emerged shore deposits (Qes) 21 Modern shore and delta deposits (Qsd)-- -- 22 Alluvial deposits (Qa)-- 23 Muskeg and other organic deposits (Qm) 24 Artificial fill (Qf) 26 Diamicton deposits or metamorphic rocks (dr) 28 Structural geology 28 Regional setting 28 Local structure 37 Earthquake probability 37 Seismicity 38 Relation of earthquakes to known or inferred faults and recency of fault movement - 48 Evaluation of seismic risk in the Metlakatla area - 50 Page Inferred effects from future earthquakes ~ 56 Effects from surface movements along faults and other tectonic land-level changes 57 Ground shaking 58 Liquefaction 59 Ground fracturing and water-sediment ejection - 60 Compaction and related subsidence 61 Earthquake-induced subaerial and underwater landslides 61 Effects of shaking on ground water and streamflow - 62 Tsunamis, seiches, and other earthquake-related water waves 63 Inferred future effects from geologic hazards other than earthquakes 71 High water waves 72 Landslides 73 Stream floods and erosion of deposits by running water 74 Recommendations for additional studies 75 Glossary ~ 77 References cited 80 n Illustrations Page Figure 1. -

An Analysis of Discourses Surrounding the Disappearance of the Kah Shakes Cove Herring (Clupea Pallasi)

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1-1-2011 Event Ecology: An Analysis of Discourses Surrounding the Disappearance of the Kah Shakes Cove Herring (Clupea pallasi) Jamie Sue Hebert Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Hebert, Jamie Sue, "Event Ecology: An Analysis of Discourses Surrounding the Disappearance of the Kah Shakes Cove Herring (Clupea pallasi)" (2011). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 5. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.5 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Event Ecology: An Ecological Analysis of Discourses Surrounding the Disappearance of the Kah Shakes Cove Herring (Clupea pallasi) by Jamie Sue Hebert A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of the Arts in Anthropology Thesis Committee: Michele Gamburd, Chair Virginia Butler Jeremy Spoon Thomas Thornton Portland State University ©2011 ABSTRACT The conflict over the herring run at Kah Shakes is complicated. In 1991, the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADFG) expanded the commercial herring sac roe fishing boundary in the Revillagigedo Channel to include Cat and Dog Islands. Native and non-Native local residents of Ketchikan -

Pages 54-144 (PDF)

WESTERNBIRDS OF THE KETCHIKAN BIRDS AREA, SOUTHEAST ALASKA Volume 40, Number 2, 2009 BIRDS OF THE KETCHIKAN AREA, SOUTHEAST ALASKA STEVEN C. HEINL, P. O. Box 23101, Ketchikan, Alaska 99901; steve.heinl@ alaska.gov ANDREW W. PISTON, P. O. Box 1116, Ward Cove, Alaska 99928; andrew.piston@ alaska.gov ABSTRACT: Historically, the Ketchikan area was visited by ornithologists only briefl y in the early 1900s, and there has been no formally published, comprehensive treatment of the avifauna of southeast Alaska. Here we outline the status of 260 species of birds that have been recorded in the Ketchikan area, southeast Alaska, including 70 confi rmed or probable breeders and 10 possible breeders, largely on the basis of our personal observations from 1990 to 2008. The avifauna of the Ketchikan area is typical of the coastal temperate rainforest but also, as a result of its location on the inner islands of the Alexander Archipelago, includes elements of both the open marine environment along the outer coast to the west and mainland river habitats to the east. The city of Ketchikan is located on Revillagigedo Island at the southern terminus of the Alexander Archipelago, just north of Dixon Entrance, in southeast Alaska (Figure 1). Ketchikan lies near the heart of the coastal temperate rainforest that stretches from northwestern California north and west along the Pacifi c coast to the Kenai Peninsula and Kodiak Island, Alaska. There has been no formally published, comprehensive treatment of the avifauna of southeast Alaska, and published information from the Ketchikan area is particularly limited. Most early ornithological explorations of southeast Alaska took place in the spring and summer, and ornithologists often spent only a short time in any one location. -

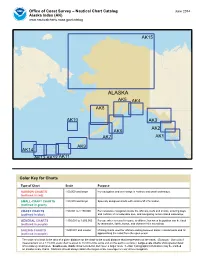

Alaska Index (AK)

Office of Coast Survey – Nautical Chart Catalog June 2014 Alaska Index (AK) www.nauticalcharts.noaa.gov/catalog AK15 ALASKA AK5 AK4 AK8 AK10 AK3 AK2 AK6 AK7 AK1 AK9 AK14 AK13 AK12 AK11 Color Key for Charts Type of Chart Scale Purpose HARBOR CHARTS 1:50,000 and larger For navigation and anchorage in harbors and small waterways. (outlined in red) SMALL-CRAFT CHARTS 1:80,000 and larger Specially designed charts with small craft information. (outlined in green) COAST CHARTS 1:50,001 to 1:150,000 For coastwise navigation inside the offshore reefs and shoals, entering bays (outlined in blue) and harbors of considerable size, and navigating certain inland waterways. GENERAL CHARTS 1:150,001 to 1:600,000 For use when a vessel’s course is offshore but when its position can be fixed (outlined in purple) by landmarks, lights, buoys, and characteristic soundings. SAILING CHARTS 1:600,001 and smaller Plotting charts used for offshore sailing between distant coastal ports and for (outlined in purple) approaching the coast from the open ocean. The scale of a chart is the ratio of a given distance on the chart to the actual distance that it represents on the earth. (Example: One unit of measurement on a 1:10,000 scale chart is equal to 10,000 of the same unit on the earth’s surface.) Large-scale charts show greater detail of a relatively small area. Small-scale charts show less detail, but cover a larger area. Certain hydrographic information may be omitted on smaller-scale charts. Mariners should always obtain the largest-scale coverage for near shore navigation. -

The Brandt's Cormorant in Alaska

NOTES THE BRANDT’s CormoranT IN ALASKA STEVEN C. HEINL, P. O. Box 23101, Ketchikan, Alaska 99901; steve_heinl@ fishgame.state.ak.us ANDREW W. PISTON, P. O. Box 1116, Ward Cove, Alaska 99928 The Brandt’s Cormorant (Phalacrocorax penicillatus) breeds along the Pacific coast of North America from Baja California north to south-coastal Alaska (AOU 1998, Wallace and Wallace 1998). In Alaska, it is a rare, local breeder, with nest- ing documented at only a few locations (Wallace and Wallace 1998). The nearest nesting locations south of Alaska are located on the west coast of Vancouver Island, British Columbia (Campbell et al. 1990). Although this species has been presumed to winter along the southern coast of Alaska (AOU 1983, AOU 1998, Wallace and Wallace 1998), there have been no formally published mid-winter records for the state. Furthermore, it has been nearly 30 years since this species’ status in Alaska has been summarized (Kessel and Gibson 1978). Here we present new informa- tion on the regular winter occurrence of the Brandt’s Cormorant in the Ketchikan area of southeast Alaska, and we provide a review of its historical occurrence in the state based on published information, including regional reports in American Birds (AB), unpublished information obtained from other observers, and unpublished data archived at the University of Alaska Museum (UAM), Fairbanks. The city of Ketchikan is located on Revillagigedo Island, one of the southernmost islands of the Alexander Archipelago in southeast Alaska (Figure 1). On the basis of Figure 1. Coastal Alaska and British Columbia, showing the Ketchikan area, Alaska (inset), and locations mentioned in the text.