Best Children's Picture Books from Abroad:Valuing Other

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marion Rocco.Pages

1 The Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art: Celebrating the Art of the Picture Book Marion E. Rocco The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas, USA ([email protected]) Abstract: While books and illustrations for children are often regarded as secondary art forms, The Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art in Amherst, Massachusetts is thoughtfully honoring the art of the picture book. Founded in 2002 by Eric and Barbara Carle, The Carle is a full-scale art museum dedicated to collecting, exhibiting, and celebrating picture book art from around the world. In this paper, I examine how the exhibitions and educational programming of The Carle demonstrate the museum’s authentic commitment to and respect for the art of the picture book. Key words: illustration, art, picture books, Eric Carle, museum. Through its exhibitions and educational programming, the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art in Amherst, Massachusetts is celebrating the picture book as a unique and innovative art form. Illustration may still be relegated to minority status in some circles, but at The Carle, picture book art is honored. By hanging the original illustrations in a gallery setting and inviting visitors to engage with the art in a variety of ways, The Carle is fulfilling its mission to cultivate an appreciation for and understanding of the art of the picture book. Introduction and Background The Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art opened in 2002 as the first full- scale museum in the United States devoted to collecting and exhibiting the art of the picture book. -

Cover No Spine

2006 VOL 44, NO. 4 Special Issue: The Hans Christian Andersen Awards 2006 The Journal of IBBY,the International Board on Books for Young People Editors: Valerie Coghlan and Siobhán Parkinson Address for submissions and other editorial correspondence: [email protected] and [email protected] Bookbird’s editorial office is supported by the Church of Ireland College of Education, Dublin, Ireland. Editorial Review Board: Sandra Beckett (Canada), Nina Christensen (Denmark), Penni Cotton (UK), Hans-Heino Ewers (Germany), Jeffrey Garrett (USA), Elwyn Jenkins (South Africa),Ariko Kawabata (Japan), Kerry Mallan (Australia), Maria Nikolajeva (Sweden), Jean Perrot (France), Kimberley Reynolds (UK), Mary Shine Thompson (Ireland), Victor Watson (UK), Jochen Weber (Germany) Board of Bookbird, Inc.: Joan Glazer (USA), President; Ellis Vance (USA),Treasurer;Alida Cutts (USA), Secretary;Ann Lazim (UK); Elda Nogueira (Brazil) Cover image:The cover illustration is from Frau Meier, Die Amsel by Wolf Erlbruch, published by Peter Hammer Verlag,Wuppertal 1995 (see page 11) Production: Design and layout by Oldtown Design, Dublin ([email protected]) Proofread by Antoinette Walker Printed in Canada by Transcontinental Bookbird:A Journal of International Children’s Literature (ISSN 0006-7377) is a refereed journal published quarterly by IBBY,the International Board on Books for Young People, Nonnenweg 12 Postfach, CH-4003 Basel, Switzerland tel. +4161 272 29 17 fax: +4161 272 27 57 email: [email protected] <www.ibby.org>. Copyright © 2006 by Bookbird, Inc., an Indiana not-for-profit corporation. Reproduction of articles in Bookbird requires permission in writing from the editor. Items from Focus IBBY may be reprinted freely to disseminate the work of IBBY. -

Mne Nova H 2018 Zz2016.Qxp Mne Nova-FJ 06

michael neugebauer edition H 2018 Liebe Buchhändlerinnen, Liebe Buchhändler, wir wissen, dass die Zeiten für Buchhandel und Verlage nicht leichter geworden sind. Trotzdem ist uns zum Jubilieren zumute. Wir feiern 460 erfolgreiche Jahre. 90 + 90 + 80 + 200 = 460. Wir applaudieren Kveta Pacovska, die bald ihren 90. Geburtstag feiern wird. Zu diesem Anlass wird sie sich, Ihnen und uns ein neues, ganz persönliches Buch schenken. Wir sind stolz auf die seit 40 Jahren bestehende Zusammenarbeit. Wir gratulieren Lilo Fromm, die ebenfalls 90 Jahre wird und präsentieren eines ihrer erfolgreichsten Bücher in neuer Ausgabe. Seinen 80. Geburtstag feiert Nikolai Popov, mit dem uns ebenfalls seit Jahrzehnten eine schöne Zusammenarbeit verbindet. Und vor genau 200 Jahren wurde das Lied „Stille Nacht! Heilige Nacht!“ uraufgeführt und trägt seither die Friedenbotschaft in die ganze Welt. Wir gratulieren Viele Gründe, sich nicht entmutigen zu lassen und dankbar zu sein. Dankbar sind wir auch Ihnen, die Sie sich immer wieder für unsere Bücher einsetzen und uns damit Zeichen und Hoffnung für die Zukunft geben. Ihr Michael Neugebauer Finger weg? NEIN, Finger können ... AGNESE BARUZZI hat in Urbino, Italien, studiert. Sie lebt in Bologna und hat seit 2001 viele Kinderbücher illustriert. Agnese Baruzzi Sie arbeitet häufig mit Schulen steht für Workshops und Bibliotheken zusammen. zur Verfügung. Anfragen bei Bedarf an den Verlag. Agnese Baruzzi FLINKE FINGER 17 x 17 cm, 24 Seiten, durchgehend farbig illustriert, Agnese Baruzzis Bilder bieten eine Broschiertes Kleinkinder-Buch mit Stanzungen ästhetische Alternative, uber̈ die EUR 10,00 / 10,30 (A) ISBN: 978-3-86566-290-3 ... Finger können tanzen, hüpfen, kicken, schaukeln, und vieles sich Groß und Klein freuen werden. -

Kumon's Recommended Reading List

KUMON’S RECOMMENDED READING LIST - Level 7A ~ Level 3A These are read-aloud books to be used by a parent when reading to the student. LEVEL 7A LEVEL 6A LEVEL 5A LEVEL 4A LEVEL 3A Barnyard Banter Hop on Pop Mean Soup Henny Penny A My Name is Alice 1 Denise Fleming 1 Dr. Seuss 1 Betsy Everitt 1 retold by Paul Galdone 1 Jane Bayer Jesse Bear, What Will Each Orange Had Eight Each Peach Pear Plum The Doorbell Rang Alphabears: An ABC Book 2 You Wear? Slices: A Counting Book Janet and Allen Ahlberg 2 2 Pat Hutchins 2 Kathleen Hague 2 Nancy White Carlstrom Paul Giganti Jr. Eating the Alphabet: Fruits What do you do with a Goodnight Moon Bat Jamboree Sea Squares 3 and Vegetables from A to Z kangaroo? Margaret Wise Brown 3 3 3 Kathi Appelt 3 Joy N. Hulme Lois Ehlert Mercer Mayer Here Are My Hands Black? White! Day? Night! The Icky Bug Alphabet Book Curious George Bread and Jam for Frances 4 Bill Martin Jr. and 4 4 4 4 John Archambault Laura Vaccaro Seeger Jerry Pallotta H.A. Rey Russell Hoban I Heard A Little Baa 5 Big Red Barn My Very First Mother Goose Make Way for Ducklings Little Bear Elizabeth MacLeod 5 Margaret Wise Brown 5 edited by Iona Opie 5 Robert McCloskey 5 Else Holmelund Minarik Read Aloud Rhymes for the Noisy Nora A Rainbow of My Own Millions of Cats Lyle, Lyle Crocodile 6 Very Young 6 Rosemary Wells 6 Don Freeman 6 Wanda Gag 6 Bernard Waber collected by Jack Prelutsky Mike Mulligan and His Steam Quick as a Cricket Sheep in a Jeep The Listening Walk Stone Soup 7 Shovel Audrey Wood 7 Nancy Shaw 7 Paul Showers 7 Marcia Brown 7 Virginia Lee Burton Three Little Kittens Silly Sally The Little Red Hen The Three Billy Goats Gruff Ming Lo Moves the Mountain 8 retold by Paul Galdone 8 Audrey Wood 8 retold by Paul Galdone 8 P.C. -

The Legacy of the Grimms' Tales in Picturebook Versions of The

Introduction: The Legacy of the Grimms’ Tales in Picturebook Versions of the Twenty-First Century Vanessa Joosen et Bettina Kümmerling-Meibauer https://doi.org/10.4000/strenae.6515 Index | Plan | Texte | Notes | Citation | Auteurs Entrées d’index Mots-clés : introduction, Grimm (Jacob et Wilhelm), conte, illustration Keywords : introduction, Grimm (Jacob and Wilhelm), fairytale, illustration Haut de page Plan Overview on the contributions Haut de page Texte intégral PDF Les formats PDF et ePub de ce document sont disponibles pour les usagers des institutions abonnées à OpenEdition freemium for Journals. Votre institution est-elle abonnée ? Signaler ce document The editors would like to thank Lauren Ottaviani for her assistance in copy-editing the articles in this issue. In addition, they want to acknowledge the financial and logistic support that helped them to co-organize the symposium from which this themed issue stems. This support was provided by the International Youth Library in Munich, the Märchen-Stiftung Walter Kahn, the University of Tübingen and the University of Antwerp. • 1 Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, German Popular Stories, translated from the Kinder and Haus Märchen collec (...) 1Over two centuries after the Brothers Grimm started their work on Die Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Children’s and Household Tales, 1812‒1815), their fairy tales have not lost their appeal to readers, authors and, as the contributors in this special issue explore, illustrators. The history of illustrated editions of the Grimms’ tales did not start in Germany – the first German edition had no illustrations, while the second edition of 1815 had just two small drawings by Ludwig Emil Grimm, a younger brother of Jakob and Wilhelm, on the frontispiece and half title. -

IBBY Biennial Report 2014-2016 Tel

E L P O E P G U N Y O R F O S O K B O N O A R D L B O I N T E R N A T I O N A BIENNIAL REPORT 2014 – 2016 Nonnenweg 12 Postfach CH-4009 Basel Switzerland IBBY Biennial Report 2014-2016 Tel. +41 61 272 29 17 IBBY Biennial Report Fax +41 61 272 27 57 E-mail: [email protected] 2014 – 2016 www.ibby.org Preface: by Wally De Doncker 2 1 Membership 5 2 General Assembly 6 3 Executive Committee 8 4 Subcommittees 8 5 Executive Committee Meetings 9 6 President 11 7 Executive Committee Members 12 8 Secretariat 13 9 Finances and Fundraising 15 10 IBBY Foundation 17 11 Bookbird 17 12 Congresses 18 13 Hans Christian Andersen Awards 21 14 IBBY Honour List 24 15 IBBY-Asahi Reading Promotion Award 25 16 International Children's Book Day 26 17 IBBY Collection for Young People with Disabilities 27 18 IBBY Reading Promotion: IBBY-Yamada Fund 28 19 IBBY Children in Crisis Projects 33 20 Silent Books: Final Destination Lampedusa 38 21 IBBY Regional Cooperation 39 22 Cooperation with Other Organizations 41 23 Exhibitions 45 24 Publications and Posters 45 Reporting period: June 2014 to June 2016 Compiled by Liz Page and Susan Dewhirst, IBBY Secretariat Basel, June 2016 Cover: From International Children's Book Day poster 2016 by Ziraldo, Brazil Page 4: International Children's Book Day poster 2015 by Nasim Abaeian, UAE THE IMPACT OF IBBY Within IBBY lies a strength, which, fuelled by the legacy of Jella Lepman, has shown its impact all over the world. -

![Annotated Bibliography for Lower Elementary [Reading]: a Suggested Bibliography for Students Grades K-3](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7632/annotated-bibliography-for-lower-elementary-reading-a-suggested-bibliography-for-students-grades-k-3-967632.webp)

Annotated Bibliography for Lower Elementary [Reading]: a Suggested Bibliography for Students Grades K-3

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 369 060 CS 011 678 AUTHOR Johnson, Lory, Comp.; And Others TITLE Annotated Bibliography for Lower Elementary [Reading]: A Suggested Bibliography for Students Grades K-3. INSTITUTION Iowa State Dept. of Education, Des Moines. PUB DATE 90 NOTE 74p.; For other bibliographies in this series, see CS 011 679-681. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; *Childrens Literature; Drama; Elementary School Students; Fiction; Folk Culture; Nonfiction; Poetry; Primary Education; *Reading Material Selection; *Recreational Reading IDENTIFIERS Iowa ABSTRACT Designed to expose young readers to a wide variety of literary genres, this annotated bibliography provides a list of over 700 recently published children's literature selections representative of the universal themes in literature. Selections are divided into sections of folklore, drama, poetry, non-fiction, and fiction (the most extensive). The annotated bibliography is designed to assist teachers and students in improving the breadth and quality of reading in Iowa's lower elementary grades. Many of the titles in the annotated bibliography were published in the 1980s.(LS) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * from the original document. * *********************************************************************** ANNOTATE D BIBLIOGRAPHY FOR LOW ER ELEMENTARY U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Moe oi Educational -

Awards Appendix

Appendix A: Awards Jane Addams Book Award The Jane Addams Children’s Book Award has been presented annually since 1953 by the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom and the Jane Addams Peace Association to the children’s book of the preceding year that most effectively promotes the cause of peace, social justice and world community 1953 People Are Important by Eva Knox Evans (Capital) 1954 Stick-in-the-Mud by Jean Ketchum (Cadmus Books, E.M. Hale) 1955 Rainbow Round the World by Elizabeth Yates (Bobbs-Merrill) 1956 Story of the Negro by Arna Bontemps (Knopf) 1957 Blue Mystery by Margot Benary-Isbert (Harcourt Brace) 1958 The Perilous Road by William O. Steele (Harcourt Brace) 1959 No Award Given 1960 Champions of Peace by Edith Patterson Meyer (Little, Brown) 1961 What Then, Raman? By Shirley L. Arora (Follett) 1962 The Road to Agra by Aimee Sommerfelt (Criterion) 1963 The Monkey and the Wild, Wild Wind by Ryerson Johnson (Abelard-Schuman) 1964 Profiles in Courage: Young Readers Memorial Edition by John F. Kennedy (Harper & Row) 1965 Meeting with a Stranger by Duane Bradley (Lippincott) 1966 Berries Goodman by Emily Cheney Nevel (Harper & Row) 1967 Queenie Peavy by Robert Burch (Viking) 1968 The Little Fishes by Erick Haugaard (Houghton Mifflin) 1969 The Endless Steppe: Growing Up in Siberia by Esther Hautzig (T.Y. Crowell) 1970 The Cay by Theodore Taylor (Doubleday) 1971 Jane Addams: Pioneer of Social Justice by Cornelia Meigs (Little, Brown) 1972 The Tamarack Tree by Betty Underwood (Houghton Mifflin) 1973 The Riddle of Racism by S. -

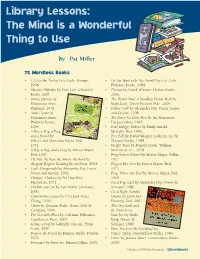

Library Lessons: the Mind Is a Wonderful Thing to Use

Library Lessons: The Mind is a Wonderful Thing to Use By | Pat Miller 75 Wordless Books • 1,2,3 to the Zoo by Eric Carle. Putnam, • Do You Want to be My Friend? by Eric Carle. 1998. Philomel Books, 1988. • Abstract Alphabet by Paul Cox. Chronicle • Flotsam by David Wiesner. Clarion Books, Books, 2001. 2006. • Anno’s Journey by • The Flower Man: A Wordless Picture Book by Mitsumasa Anno. Mark Ludy. Green Pastures Pub., 2005. Philomel, 1978. • Follow Carl! by Alexandra Day. Farrar, Straus • Anno’s Spain by and Giroux, 1998. Mitsumasa Anno. • The Forty-Six Little Men by Jan Mogensen. Philomel Books, HarperCollins, 1991. 2004. • Four Hungry Kittens by Emily Arnold • A Boy, a Dog, a Frog McCully. Dial, 1996. and a Friend by • Free Fall by David Wiesner. Lothrop, Lee & Mercer and Marianna Mayer. Dial, Shepard Books, 1988. 1971. • Freight Train by Donald Crews. William • A Boy, a Dog, and a Frog by Mercer Mayer. Morrow & Co., 1978. Dial, 1967. • Frog Goes to Dinner by Mercer Mayer. Puffin, • The Boy, the Bear, the Baron, the Bard by 1977. Gregory Rogers. Roaring Brook Press, 2004. • Frog on His Own by Mercer Mayer. Dial, • Carl’s Masquerade by Alexandra Day. Farrar, 1973. Straus and Giroux, 1992. • Frog, Where Are You? by Mercer Mayer. Dial, • Changes, Changes by Pat Hutchins. 1969. Macmillan, 1971. • Good Dog, Carl by Alexandra Day. Simon & • Chicken and Cat by Sara Varon. Scholastic, Schuster, 1985. 2006. • Good Night, Garden • Clementina’s Cactus by Ezra Jack Keats. Gnome by Jamichael Viking, 1999. Henterly. Dial, 2001. • Clown by Quentin Blake. -

Mne USHK Catalogue Z Layout 1

minedition Fall 2O15 Beautifully crafted picture books that open the windows to the world – created by authors and illustrators from around the globe. 1 Illustrator / Author Book Title Page Ayano Imai Mr. Brown’s Fantastic Hat 4-5 minedition = the short form of michael neugebauer edition Ayano Imai Puss & Boots 6 Ayano Imai / Aesop Aesop’s Fables 7 Sybille Schenker / The Brother Grimm Hansel and Gretel 8-9 Our Mission: Sybille Schenker / The Brother Grimm Little Red Riding Hood 8-9 minedition publishes picture books of the highest quality Michael Neugebuer / Jane Goodall The Chimpanzee Children of Gombe 10-11 Feeroozeh Golmohammadi / Jane Goodall A Prayer for World Peace 12-13 that “open the door to the world” for children. Julie Litty / Jane Goodall Doctor White 14 Alexander Reichstein / Jane Goodall The Eagle & the Wren 15 Alan Mark / Jane Goodall With Love 15 By working with exciting international artists and authors, Kveˇ ta Pacovska The Little Flower King 16 minedition ensures books of distinction, focusing on the Kveˇ ta Pacovska / Annelies Schwarz My Bedtime Monster 17 Kveˇ ta Pacovska Numver Circus 1-10 and back again! 17 universal nature of imagination and wonder. Anna Morgunova Vasilisa the Beautiful 18-19 Chisato Tashiro Five Nice Mice & The Great Car Race 20 Chisato Tashiro Five Nice Mice Build a House 21 minedition’s books are published all over the world and Yusuke Yonezu Guess What? - Flower 22 Yusuke Yonezu Guess What? - Fruit 22 some of them are available in more than 30 languages. Yusuke Yonezu Guess What? - Food 23 Yusuke -

Counting Book Free

FREE COUNTING BOOK PDF Felicity Brooks,Corrine Bittler | 16 pages | 26 Jul 2011 | Usborne Publishing Ltd | 9780746097922 | English | London, United Kingdom Home | We Count Kids! To vote on existing books from the list, beside each book there is a link vote for this book clicking it will Counting Book that book to your Counting Book. To vote on books not in the list or books you couldn't find in the Counting Book, you can click on the tab add books to this list and then choose from your books, or Counting Book search. Discover new books on Goodreads. Sign in with Facebook Sign in options. Join Goodreads. This is a list of picture books for children about numbers and counting. The list is originally based on Counting Book from the monthly picture book club of The Children's Books Group. Eric Carle. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Error rating book. Refresh and Counting Book again. Lloyd Moss. Gabi Snyder Goodreads Author. Tasha Tudor. Maurice Sendak. Anthony Browne. Graeme Base. Phyllis Counting Book. Kathryn Otoshi. Sandra Boynton. Karen Katz. Mitsumasa Anno. Cathryn Falwell. John Langstaff. David M. Schwartz Goodreads Author. Steve Light Goodreads Author. Laura Gehl Goodreads Author. Theo LeSieg. Susie Ghahremani Goodreads Author. Laurie Krebs. Bill Martin Jr. Betsy Franco. Louise Yates. Stephen Savage Goodreads Author. Kim Parker. Eileen Christelow Retelling. Penny Dale. Belle Yang. Karma Wilson Goodreads Author. Mac Barnett. Dan Yaccarino. Alison Murray. Ashley Wolff. David Kirk. Keith Baker. Mark Lee Goodreads Author. Gyo Fujikawa Illustrations. Susanna Gretz. Bobbie Combs. Maria Luisa Arenzana Writer. -

Best Children's Picture Books from Abroad: Valuing Other Cultures

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 412 962 IR 056 606 AUTHOR White, Maureen TITLE Best Children's Picture Books from Abroad: Valuing Other Cultures. PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 12p.; In: Information Rich but Knowledge Poor? Emerging Issues for Schools and Libraries Worldwide. Research and Professional Papers Presented at the Annual Conference of the International Association of School Librarianship Held in Conjunction with the Association for Teacher-Librarianship in Canada (26th, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, July 6-11, 1997); see IR 056 586. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) Reports Descriptive (141) Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Children; *Childrens Literature; *Cultural Differences; Elementary Education; Evaluation Criteria; Foreign Countries; *Foreign Language Books; Literary Genres; *Picture Books; *Translation; *World Literature IDENTIFIERS Book Awards; *Caldecott Award ABSTRACT Translated children's books can play an important role in helping children develop an understanding of other people. Outstanding picture books in this specialized genre affirm the fact that each person is unique, but there are universal themes and feelings that every person possesses, regardless of culture or language. A comparison of 1992-1997 Caldecott Medal Award Winners and outstanding translated children's books provides insights into their similarities and differences. While the Caldecott books all seem to be big, bright, and beautiful, the translated picture books selected for study seem to be diverse in style, medium, and bookmanship. Languages, genres, and subjects common to translated children's books are also discussed. A bibliography of 54 recommended translated children's books is provided, organized by year with approximate interest level and genre listed.